By Mark Kissling

Last year the Associated Press reported that, in 2010, Mitch Daniels, then Governor of Indiana, welcomed the unexpected death of the historian and activist Howard Zinn. In a series of emails to state education officials, Daniels wrote, “This terrible anti-American academic has finally passed away” (LoBianco, 2013a, paragraph 8). Shortly after his emails were made public through a Freedom of Information Act request, Daniels—now the President of Purdue University— stood by what he wrote several years before. Purdue’s board of trustees supported him as well, despite deep concerns about academic freedom by many of the university’s faculty members (LoBianco, 2013b).

Last year the Associated Press reported that, in 2010, Mitch Daniels, then Governor of Indiana, welcomed the unexpected death of the historian and activist Howard Zinn. In a series of emails to state education officials, Daniels wrote, “This terrible anti-American academic has finally passed away” (LoBianco, 2013a, paragraph 8). Shortly after his emails were made public through a Freedom of Information Act request, Daniels—now the President of Purdue University— stood by what he wrote several years before. Purdue’s board of trustees supported him as well, despite deep concerns about academic freedom by many of the university’s faculty members (LoBianco, 2013b).

Academic freedom was an issue because Daniels, in one of his 2010 emails, sought to censure Zinn’s most famous book, A People’s History of the United States (1980/2003), from Indiana’s classrooms. Referring to Zinn’s book, Daniels wrote, “It is a truly execrable, anti-factual piece of disinformation that misstates American history on every page” (LoBianco, 2013a, paragraph 8). Daniels wanted the book stricken from all high schools and colleges in the state. When he then learned that the book was being taught in a course for teachers at Indiana University, he responded, “This crap should not be accepted for any credit by the state. No student will be better taught because someone sat through this session” (paragraph 11). Daniels did not want any students reading A People’s History, particularly teachers who might bring the text into their own classrooms.

I have taught A People’s History for over a decade, in both high school and college classrooms. When I learned of Daniels’ emails, I read the wide range of commentaries about his statements closely (e.g., Bigelow, 2013; Wood, 2013) and I was moved to reflect on my experiences teaching A People’s History. What follows is that reflection, written as a narrative spanning the last decade and a half.

My purpose here is to argue, contrary to Governor Daniels, that students have much to gain from reading A People’s History in their classrooms. For that reason, I encourage all history teachers to bring Zinn’s writings into their classrooms. To whatever degree debates are ongoing about the suitability of A People’s History as a learning resource in classrooms, I hope those debaters siding against Zinn’s book will consider my positive experiences teaching with it. Even if critics dislike Zinn’s perspective on U.S. History (which I clearly find important and meaningful), they should consider that Zinn’s work is a wonderful resource for critical inquiry. I have found this to be the case at all the levels and places of schooling where I have taught A People’s History.

My Introduction to Zinn and His Work

I first came across Howard Zinn and A People’s History in New Hampshire in the summer of 2001. I was about to enter my senior year at Dartmouth College, where I was a history major, education minor, and enrolled in the teacher education program. That fall I would pre-service teach at nearby Lebanon High School (LHS). Prior to the start of school, my mentor teacher, Bill Murphy, gave me a copy of A People’s History. It was for his Advanced Placement (AP) U.S. History class, which I would co-teach with him. That course’s required books were a traditional AP textbook and Zinn’s book.

When Bill handed me the latter, he said, “Now you’ve read Zinn before, right?” I hadn’t, and it surprised him. He figured since I was a history major that I was familiar with Zinn’s work. Embarrassed, I shrugged my shoulders and wondered what I had been missing—and why. For the next couple weeks, as I prepared for my teaching, I read as deep into A People’s History as I could. I was enthralled by it. Although I was a veteran of many high school and college history classes, I had never encountered anything like it. Never before had a book that I read confronted so candidly and extensively my country’s history of unjust treatment of marginalized and powerless peoples. As I was in the process of developing a teaching identity founded on a strong commitment to democracy and social justice, Zinn’s book quickly became for me a valuable pedagogical resource.

When Bill handed me the latter, he said, “Now you’ve read Zinn before, right?” I hadn’t, and it surprised him. He figured since I was a history major that I was familiar with Zinn’s work. Embarrassed, I shrugged my shoulders and wondered what I had been missing—and why. For the next couple weeks, as I prepared for my teaching, I read as deep into A People’s History as I could. I was enthralled by it. Although I was a veteran of many high school and college history classes, I had never encountered anything like it. Never before had a book that I read confronted so candidly and extensively my country’s history of unjust treatment of marginalized and powerless peoples. As I was in the process of developing a teaching identity founded on a strong commitment to democracy and social justice, Zinn’s book quickly became for me a valuable pedagogical resource.

The class that Bill and I taught had a weekly cycle. At the beginning of each week students read the relevant chapters in the textbook and A People’s History related to that week’s topic. (Colonial America and Westward Expansion were examples of topics.) After various mid-week activities—like role-plays, research, and artifact analysis—each Friday’s class, then, featured what Bill termed the “Circle of Pain.” It was a discussion led by two people (i.e., the teachers in the first two weeks; the students from Week 3 onward) but everyone sat in a circle. Students and teachers alike were encouraged to grapple with (and often debate) the representations of the week’s topic, and their meanings, in the two different texts.

The Circle of Pain was painful because it made explicit many important, uncomfortable questions that often go unasked and unconsidered in history classes. Should the U.S. celebrate Columbus Day? What was slavery’s role in the rise of the U.S., and what is slavery’s legacy today? Was the dropping of the bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki just?  And so forth. At the start of this weekly practice, it was mostly Bill and me that raised critical questions like these to the group. However, as our students read and (re)considered their past history learning, their critical questions came to guide our discussions. It was a student that first made explicit a critical question embedded in the structure of The Circle of Pain: why are there different histories about the same topic? This hugely important question is one too seldom raised in history classrooms.

And so forth. At the start of this weekly practice, it was mostly Bill and me that raised critical questions like these to the group. However, as our students read and (re)considered their past history learning, their critical questions came to guide our discussions. It was a student that first made explicit a critical question embedded in the structure of The Circle of Pain: why are there different histories about the same topic? This hugely important question is one too seldom raised in history classrooms.

As our students had many years of traditional textbook reading under their belts, we gave them little structure for reading those chapters. However, for A People’s History Bill developed a structure that he called “Zinn and the Art of the Dialectical Journal,” playing off the title (and, implicitly, some of the content) of a favorite book of his, Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance (Pirsig, 1974/2006). At the start of each week, everyone drew a line down the center of a sheet of notebook paper (and this became sheets through the week). On the left side, as we read, we jotted down important facts, ideas, and analyses. On the right we offered thoughts and questions in response to the bullet points on the left side. One of the purposes in doing this was to make clear that the students themselves are central to the telling, writing, and interpreting of history. We all make history, and make it meaningful—not just the historians.

Several weeks into the school year, and thinking about a teacher education assignment that asked me to do “something special” at my school, I hatched an idea: I would see if I could get Zinn to speak to my class. This was prior to classroom technologies like Skype and LCD projectors, which can fairly easily bring a guest speaker to an equipped classroom. Rather, Zinn—at that point an emeritus professor at Boston University—lived two hours away from my school. Perhaps, I thought, he could come in person to my classroom. But also thinking that it was probably a long shot that he would drive that distance for one hour of talk with 30 students and two teachers, I went to see my favorite history professor at Dartmouth. Perhaps Zinn could give a talk at Dartmouth, maybe funded by the History Department there, and also talk to my class at LHS. No professor had previously mentioned Zinn in a class, and Dartmouth and its History Department had a strong reputation for political conservatism, but wouldn’t professors and students jump at the chance to hear and question Zinn?

No. The professor told me flat out: “We don’t care for his history here.” Upon hearing this I was crushed. What does that mean? But “his history” makes history come to life in my classroom! The implicit message was that history is singular and uncontested, that there is no room for inquiry and debate. We kept reading Zinn at LHS, but I dropped my idea to bring him to the school. I was hurt by the professor’s rejection of my idea. He was an esteemed academic, someone that I looked up to. I loved A People’s History, but it became taboo.

No. The professor told me flat out: “We don’t care for his history here.” Upon hearing this I was crushed. What does that mean? But “his history” makes history come to life in my classroom! The implicit message was that history is singular and uncontested, that there is no room for inquiry and debate. We kept reading Zinn at LHS, but I dropped my idea to bring him to the school. I was hurt by the professor’s rejection of my idea. He was an esteemed academic, someone that I looked up to. I loved A People’s History, but it became taboo.

Teaching A People’s History in a New High School Context

In the late summer of 2004, I began my first year as a fulltime teacher, teaching social studies at Framingham High School (FHS) in Massachusetts. Unlike LHS, where the vast majority of my students were U.S.-born whites, the student population of Framingham was more diverse, particularly with a sizable first-generation immigrant population. I was assigned to teach three sections of sophomore-level U.S. History I (i.e., up through the Compromise of 1877). I issued my students the school’s textbook for that course, and then I made classroom photocopies of snippets of A People’s History. My students read the textbook for homework, and in class we read Zinn.

My FHS students weren’t as old and well read as my LHS students during my pre-service teaching days, so I developed a handful of scaffolded ways for us to interact with the text. We would group-read as a class, processing it together, or read tiny chunks in small groups with guiding questions. I found both of these strategies helpful for breaking down some of Zinn’s more complex arguments. Importantly, what Zinn wrote wasn’t sanitized; it was just made more easily understandable. Students would also construct a version of “Zinn and the Art of the Dialectical Journal.” As at LHS, this strategy proved to be a useful organizer of ideas, arguments, opinions, and questions.

Additionally, we would break the book snippets into segments, with groups reading and acting out each one. Drama in a history classroom is often a hook for students, and Zinn’s prose lends itself nicely to the imagination of student playwrights. (Skits about the Arawaks and the Spaniards at the start of each school year always set an exciting tone for what students would be doing in our class over the course of the year.) We always concluded units by painfully struggling with the discrepancies between A People’s History and the textbook. When, for example, the textbook omitted labor strikes that Zinn highlighted, students were left to consider each text’s motivations. The same was true when Zinn left out the chronology and detail of battles that were featured so prominently in the textbook.

My purpose in teaching with A People’s History, as with Bill’s Circle of Pain, was to call into question the longstanding narratives (like American exceptionalism) that my students had learned in much, if not all, of their prior schooling. I wanted them to think, question, study, and decide for themselves. I also wanted them to understand how history is positioned by historiography. By this time I had read another of Zinn’s books, Declarations of Independence (1991), and I used an excerpt from it in which he openly lays out (unlike many history writers) his biases:

Writing this book, I do not claim to be neutral, nor do I want to be. There are things I value, and things I don’t. I am not going to present ideas objectively if that means I don’t have strong opinions on which ideas are right and which are wrong. I will try to be fair to opposing ideas by accurately representing them. But the reader should know that what appear here are my own views of the world as it is and as it should be.

I do want to influence the reader. But I would like to do this by the strength of argument and fact, by presenting ideas and ways of looking at issues that are outside the orthodox. I am hopeful that given more possibilities people will come to wiser conclusions. (Zinn, 1991, p. 7)

My teaching of A People’s History gained a boost when I learned that the teacher who was assigned to mentor me, Jeff Sudmyer, also frequently used Zinn’s prominent text in his teaching. On top of that, Jeff got our department head to agree to use some of our allotted book money to purchase a classroom set of A People’s History. In a department of more than 20 teachers, Jeff and I pretty much shared the two classroom sets for the remainder of the year. Jeff also shared with me a number of teaching activities—like running a mock trial in class of the Union leadership for war crimes during the Civil War—that asked students to grapple with some of the toughest questions of U.S. history. This, I believe, was one of Zinn’s central missions.

Jeff left my school the following year to run another school. Fortuitously, a new colleague who also used Zinn’s work in his teaching, Chris Martell, joined the faculty in Jeff’s stead. For the next two years, I housed the department’s sets of A People’s History. What a privilege it was to pass out copies of the book on just about any day. For the most part, I only needed to negotiate with Chris, whose room abutted mine, when I planned to use the books.

In the summer of 2006, on my vacation from school, I began attending weekly war protests in Harvard Yard, which was about a 15-minute walk from my apartment. Sometimes our modest-sized group would crisscross the yard in silence, each person holding a sign with the name of a fallen civilian or soldier in Afghanistan or Iraq. Other times we would rally with the inspiration of several speakers. On a few occasions, Zinn was one of those speakers.

I began to learn more about Zinn’s fascinating life. I read You Can’t be Neutral on a Moving Train (1994), what he called “a personal history of our times,” and I watched a documentary (by the same name) about his life that came out that summer (Ellis & Mueller, 2004). After growing up poor in New York City, Zinn labored on shipping docks until enlisting in the Air Force and dropping bombs in Europe during World War II.  When the war was over, thanks to the GI Bill, he earned multiple educational degrees, including a Ph.D. in history from Columbia. Teaching at Spelman College, he was active in the Civil Rights Movement; teaching at Boston University, he was active in the movement protesting the Vietnam War. These lived experiences shaped his teaching, writing, and activism; they helped him understand that history is personal and powerful.

When the war was over, thanks to the GI Bill, he earned multiple educational degrees, including a Ph.D. in history from Columbia. Teaching at Spelman College, he was active in the Civil Rights Movement; teaching at Boston University, he was active in the movement protesting the Vietnam War. These lived experiences shaped his teaching, writing, and activism; they helped him understand that history is personal and powerful.

When I returned to FHS in the fall, Chris and I resurrected my hope from my pre-service teaching days: bring Zinn to the school. As the United States was mired in war overseas and “homeland security” was becoming a controversial phrase, we felt Zinn’s live voice was important for students to hear. I wrote to Zinn and asked if he was interested in speaking to our students. He responded enthusiastically, but he couldn’t do it immediately as he was traveling for performances related to his recent edited book Voices of a People’s History of the United States (Zinn & Arnove, 2004) and many previously scheduled talks.

Around the same time I ordered a copy of Bill Bigelow’s The Line Between Us (2006), a resource for teaching about immigration and the Mexico/United States border. One of the centerpiece activities in it, which I taught, is a tea party role-play structured by Zinn’s chapter in A People’s History “We Take Nothing By Conquest, Thank God.” I also started having my students read and dramatize some of the historical documents in Voices of a People’s History, like Joseph Plumb Martin’s A Narrative of Some of the Adventures, Dangers and Sufferings of a Revolutionary Soldier; Tecumseh’s speech to the Osages; and Sojourner Truth’s “Ain’t I a Woman?” Zinn had become pivotal to my teaching.

Around the same time I ordered a copy of Bill Bigelow’s The Line Between Us (2006), a resource for teaching about immigration and the Mexico/United States border. One of the centerpiece activities in it, which I taught, is a tea party role-play structured by Zinn’s chapter in A People’s History “We Take Nothing By Conquest, Thank God.” I also started having my students read and dramatize some of the historical documents in Voices of a People’s History, like Joseph Plumb Martin’s A Narrative of Some of the Adventures, Dangers and Sufferings of a Revolutionary Soldier; Tecumseh’s speech to the Osages; and Sojourner Truth’s “Ain’t I a Woman?” Zinn had become pivotal to my teaching.

The following year I left FHS in order to attend graduate school but my colleague Chris persisted with an invitation for Zinn to visit the school. Zinn eventually came to FHS in the winter of 2008. Although I was unable to attend the talk, the school’s video production students filmed it. Zinn spoke to an auditorium crowded with students (since Chris made sure that many students beyond his own attended). As students were focused on the presidential election, one of Zinn’s main points was that citizenship entails much more than voting once every four years. Rather, he said, citizenship requires action every single day. Reminiscent of what Joel Westheimer calls “democratic patriotism” (2007), Zinn challenged students to be patriotic: “don’t merely obey the government . . . think of the principles that the government is supposed to stand for; if the government doesn’t uphold those principles, your job is to take it to task.” The message was that citizens, students included, are the agents of democracy, not the government, which echoes an oft-made point in Zinn’s writings that history is the domain of the citizen, not merely the historian.

Teaching A People’s History with Pre-Service Teachers

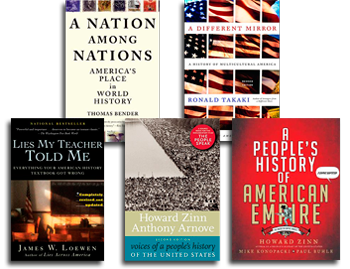

Additional books Kissling used to help pre-service students think about teaching a dynamic, authentic social studies that was founded on critical inquiry.

Although I moved from teaching high school social studies at FHS to pre-service social studies teaching methodologies at Michigan State University (MSU), I continued to assign A People’s History, this time for my teachers-to-be. My purpose, in this context, was to help my students think about teaching a dynamic, authentic social studies that was founded on critical inquiry. I framed A People’s History as a “counternarrative” to traditional textbooks. (Other counternarratives that I used included Thomas Bender’s A Nation Among Nations, 2006, and Ronald Takaki’s A Different Mirror, 1993; we also read from James Loewen’s Lies My Teacher Told Me, 1995.) As with my high school students, we read some of Zinn’s other writings. We planned lessons around some of the documents in Voices of a People’s History. Zinn resonated with my students, especially his A People’s History of American Empire (Zinn, Konopacki, & Buhle, 2008), which is a graphical history that some of my students sought out and began using in their teaching.

Influenced by Zinn, we talked about the need for authors—and historians in particular—to state and explore their biases, to acknowledge that their histories are not the indisputable, all-encompassing truth that we might call “History” with a capitol “H.” Furthermore, we considered how any history is always in the midst of a current (or currents); a historian is never left sitting idle on the banks. I urged students, whether they agreed with Zinn’s opinions or not, to consider how perspectives other than orthodox are essential to critical historical inquiry and social studies learning aimed at fostering effective citizens.

To be sure, some of my pre-service teachers, as well as some of my high school students before them, bristled as they read parts of A People’s History. They felt Zinn failed to adequately celebrate “great” aspects of American history, or they felt Zinn was too subjective. And some felt Zinn was too cavalier in his dismissal of the work of other historians. But as other groups of students reacted to Zinn in ways I had—finding so much promise in his history—we had terrific debates about Zinn, the writing and teaching of history, and U.S. history itself. Regardless of how students took to Zinn’s writings, there was consensus about the importance of including his perspective in the curriculum, just as there was consensus that texts from many other orientations needed to be included as well.

Now and Moving Forward

For the past three years I have taught social studies teaching methodologies courses at Penn State University (PSU). Whereas at MSU I was teaching solely secondary pre-service teachers, at PSU I have worked with pre-service teachers across the elementary, middle, and high school continuum. Some of my most memorable moments teaching A People’s History have come in my course for pre-service elementary teachers, offered each fall semester. During this course, the students teach part-time in local schools where Columbus Day, Veteran’s Day, and Thanksgiving are important topics in the curriculum. Having read from Zinn’s book, the students grapple with how to teach about these holidays, even in Kindergarten classrooms, in ways that frame history as inquiry, not as a seamless, often simplistically patriotic narrative that omits oppression and struggle. They are confronted with wading into the complexity of teaching multiple histories.

My teaching of Zinn’s work over the past years is not an anomaly. Thanks, in part, to groups like the Zinn Education Project, Teaching for Change, and Rethinking Schools—A People’s History is a resource in many classrooms across the country. Zinn, though, is as controversial as ever. As I read the stories about Mitch Daniels’ emails, I came across an article published by Stanford history education professor Sam Wineburg (2012-2013) several months before the Daniels story emerged. Wineburg takes issue with the “undue certainty” of A People’s History. Focusing on the book’s chapter on World War II, he chides Zinn for making grand claims based on thin anecdotal evidence, utilizing “yes-type” questions that provide the reader little room for divergent thinking, and disregarding the chronology of events.

While I believe Wineburg offers several legitimate criticisms of A People’s History (e.g., that the book possesses some of the same faults as traditional textbooks, like failing to provide footnotes), I strongly disagree with what seems to be the implicit message of the article: that A People’s History is a problematic text for a history classroom. My years of teaching with it lead me to believe the opposite: A People’s History is a terrific text for a classroom set on teaching and learning critical inquiry.

All texts are problematic in a classroom if there is no grappling with them. Absent this grappling, what ensues is Freire’s (1970/1993) “banking method,” in which the text (or teacher) metaphorically dumps “facts” into a student’s brain and calls it a day. But A People’s History—provocative and framed counter to many history education materials—demands critical inquiry from teachers and students. It simply doesn’t jibe with the “best story” narratives (Seixas, 2000) that are coursing through much of American society—even if, as Wineburg argues, A People’s History is its own narrative of “unalloyed certainties” (p. 34). Further, the criticisms in Wineburg’s article offer entry points for challenging Zinn. As there is much to unpack with respect to content and form, these criticisms are actually reasons why Zinn’s book is a great resource for a classroom that runs on critical interaction with texts.

All texts are problematic in a classroom if there is no grappling with them. Absent this grappling, what ensues is Freire’s (1970/1993) “banking method,” in which the text (or teacher) metaphorically dumps “facts” into a student’s brain and calls it a day. But A People’s History—provocative and framed counter to many history education materials—demands critical inquiry from teachers and students. It simply doesn’t jibe with the “best story” narratives (Seixas, 2000) that are coursing through much of American society—even if, as Wineburg argues, A People’s History is its own narrative of “unalloyed certainties” (p. 34). Further, the criticisms in Wineburg’s article offer entry points for challenging Zinn. As there is much to unpack with respect to content and form, these criticisms are actually reasons why Zinn’s book is a great resource for a classroom that runs on critical interaction with texts.

In an environment predicated on inquiry, there is a place for most any text. What matters most is that there is a diversity of thought in, and authorship of, the texts being used, and that all of the texts are considered critically: Who wrote it? Why? What are its claims? What does it leave out? Who benefits from it? And so forth. As Zinn makes clear about his own books, no text—including all textbooks—is neutral. The takeaway is that all people—every single student sitting in the classroom, as well as everyone else outside of it—matter in the workings of communities toward peace and justice.

Mark Kissling is an assistant professor of education in the Department of Curriculum and Instruction at Penn State. Kissling’s teaching and research interests examine the intersections of citizenship, patriotism, sustainability, and lived experience in and related to education. In 2013 Kissling received the Woody Guthrie Research Fellowship from the BMI and Woody Guthrie Foundations. He is currently working on a research project studying the history (and present) of Guthrie’s “This Land Is Your Land” in U.S. schools.

Mark Kissling is an assistant professor of education in the Department of Curriculum and Instruction at Penn State. Kissling’s teaching and research interests examine the intersections of citizenship, patriotism, sustainability, and lived experience in and related to education. In 2013 Kissling received the Woody Guthrie Research Fellowship from the BMI and Woody Guthrie Foundations. He is currently working on a research project studying the history (and present) of Guthrie’s “This Land Is Your Land” in U.S. schools.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn