By Lauren Cooper

The months of October and November are often the only time students learn about Native Americans, and usually in the past tense or as helpless “wards of the state.”

To counter this, we offer this collection of recent Native movements and activists who have continued to struggle for sovereignty, dignity, and justice for their communities. The financial and colonial drive that usurps Native peoples ways of life is not just relegated to the past; it continues today. Here are just a few stories of struggle and achievement since the late 1960s.

For Native American Heritage Month (and beyond), view lessons and resources at the Zinn Education Project.

If you have stories to add, email us at zep@zinnedproject.org.

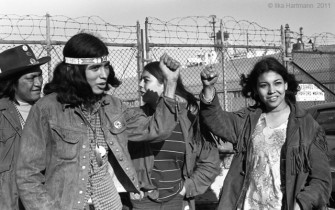

1969: Activists Began a 19-month Occupation of Alcatraz Island

On Nov. 20, 1969, a fleet of wooden sailboats holding 90 Native Americans landed on Alcatraz Island in the San Francisco Bay. For the next 19 months, the group occupied the island, hoping to reclaim the rock “in the name of all American Indians.” In their proclamation, activists stated that Alcatraz was “more than suitable for an Indian reservation, as determined by the white man’s own standards” in that:

- It is isolated from modern facilities, and without adequate means of transportation.

- It has no fresh running water.

- It has inadequate sanitation facilities.

- There are no oil or mineral rights.

- There is no industry and so unemployment is very great.

- There are no health-care facilities.

- The soil is rocky and non-productive, and the land does not support game.

- There are no educational facilities.

- The population has always exceeded the land base.

- The population has always been held as prisoners and kept dependent upon others.

The occupiers’ list of demands included the return of Alcatraz to the American Indians and sufficient funding to build, maintain, and operate an Indian cultural complex and a university.

Learn more in this profile of the Alcatraz Occupation and the film, Alcatraz Is Not an Island, by James M. Fortier.

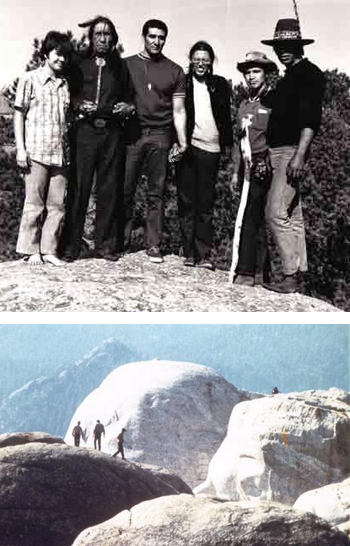

Occupiers on top of Mt. Rushmore. Images: Reclaiming Our Sacred Sites Flickr page.

1970: Activists Occupy Mount Rushmore

On August 29, 1970, members of the United Native Americans, with support from the American Indian Movement, occupied Mount Rushmore to reclaim the land that had been promised to the Oceti Sakowin (The Great Sioux Nation) in the 1868 Treaty of Fort Laramie in perpetuity. When gold was found in the mountains, prospectors migrated there in the 1870s and the federal government forced the Sioux to relinquish the Black Hills portion of their reservation. When park officials asked protesters how long they intended to stay, UNA president Lehman Brightman replied, “As long as the grass grows, the water flows, and the sun shines.” This phase referenced President Jackson’s, then General, promise to protect the life and land of the Native people of Mississippi before his massive campaign to exterminate them.

[Description adapted from “The American Experience: Native Americans and Mount Rushmore” and the international Indian newspaper, War Path.]Watch a CBS new broadcast covering the 1970 occupation. Read more about the reclamation of the Black Hills in the article, “Reclaiming the Sacred Black Hills,” by Ruth Hopkins at Indian Country Today.

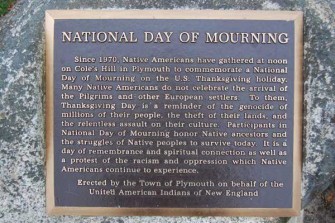

1970: First National Day of Mourning Occurs After Speech Censorship

On November 26, 1970, American Indian Movement (AIM) activists occupied Plymouth Rock, Massachusetts. Known as the National Day of Mourning, this annual event was sparked by Commonwealth of Massachusetts officials censoring a speech to be given by Frank James (Wamsutta), an Aquinnah Wampanoag, at the 350th anniversary of the landing of the Pilgrims. The reason given was “. . . the theme of the anniversary celebration is brotherhood and anything inflammatory would have been out of place.” James’ speech included many harsh truths. “History gives us facts and there were atrocities,” James wrote and went on to recall the loss of language, culture, land, and life. However, his speech closed with a call for a new beginning:

Our spirit refuses to die. . . We are uniting. . . We stand tall and proud, and before too many moons pass we’ll right the wrongs we have allowed to happen to us. We forfeited our country. Our lands have fallen into the hands of the aggressor. We have allowed the white man to keep us on our knees. What has happened cannot be changed, but today we must work towards a more humane America, a more Indian America, where men and nature once again are important; where the Indian values of honor, truth, and brotherhood prevail. You the white man are celebrating an anniversary. We, the Wampanoags, will help you celebrate in the concept of a beginning. It was the beginning of a new life for the Pilgrims. Now, 350 years later it is a beginning of a new determination for the original American: the American Indian.

Today, the National Day of Mourning is meant to be “a day of remembrance and spiritual connection as well as a protest of the racism and oppression which Native Americans continue to experience.”

Read the full speech and learn more about the National Day of Mourning.

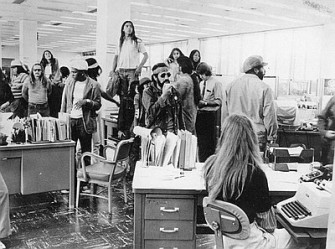

1972: Trail of Broken Treaties Caravan Arrives in Washington, D.C.

On Nov. 3, 1972, protesters from the Trail of Broken Treaties Caravan occupied the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) offices in Washington, D.C. for six days. The protesters 20-Point Manifesto begins:

We seek a new American majority — a majority that is not content merely to confirm itself by superiority in numbers, but which by conscience is committed toward prevailing upon the public will in ceasing wrongs and in doing right.

Continue reading the manifesto at the AIM website.

Read reflections on the occupation by Suzan Shown Harjo in the article, “Trail of Broken Treaties: A 30th Anniversary Memory,” at Indian Country News.

1972: AIM Opens “Survival Schools”

1972: AIM Opens “Survival Schools”

In 1972, the American Indian Movement (AIM) organizers and parents in the Minneapolis area started their own community schools as an alternative to public and Bureau of Indian Affairs (now Bureau of Indian Education) schools with high dropout rates. Clyde Bellecourt remembers, “We were losing our children during this time; juvenile courts were sweeping our children up, and they were fostering them out, and sometimes whole families were being broken up.”

Known as survival schools for their focus on basic learning and living skills, the schools strongly promoted Indian culture. [Description adapted from Education Week’s “A History of American Indian Education” by Jon Reyhner.]

Read more in the book, Survival Schools: The American Indian Movement and Community Education in the Twin Cities, by Julie Davis (University of Minnesota Press, 2013).

Image: “We Shall Remain,” PBS

1973: Activists Occupy Wounded Knee

On Feb. 27, 1973, about 250 Sioux Indians, led by members of the American Indian Movement, converged on South Dakota’s Pine Ridge Reservation, launching the famous 71-day occupation of Wounded Knee.

Set in the same impoverished village as the 1890 Wounded Knee Massacre, the occupation called global attention to unsafe living conditions and generations of mistreatment from federal and local agencies. The occupation, which began during the evening of February 27, is hailed as one of AIM’s greatest successes.

“In a way, it was a very beautiful experience,” said Len Foster, a Navajo man who joined AIM in 1970 and was at Wounded Knee for the entire 71 days. “It was a time to look at the commitment we made and a willingness to put our lives on the line for a cause.”

Continue reading the article by “Native History: AIM Occupation of Wounded Knee Begins,” by Alysa Landry at Indian Country Today.

Watch the film, Incident at Oglala, by Michael Apted.

Image: Oregon Historical Society.

1975: Protesters Take Over of Bonneville Power Administration

On August 15, 1975, 100 Native American protesters took over the Bonneville Power Administration (BPA) building in Portland, Oregon, in response to the killing of Joseph Stuntz, member of the American Indian Movement (AIM).

Two years after the occupation of Wounded Knee, Stuntz was involved in a controversial shootout with FBI agents on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota and was killed. Protesters at the BPA building demanded an end to the undeclared state of martial law in South Dakota, and restitution for Stuntz’s young widow.

Read more at the Oregon History Project.

1978: Longest Walk Begins

On July 15, 1978, a peaceful transcontinental trek for Native American justice, which had begun with a few hundred departing Alcatraz Island, California, ended this day when they arrived in Washington, D.C. accompanied by 30,000 marchers. They were calling attention to the ongoing problems plaguing Indian communities, such as lack of jobs, housing, health care, as well as dozens of pieces of legislation before Congress canceling treaty obligations of the U.S. government toward various Indian tribes.

Read more in the articles, “Indians End Longest Walk in Washington DC on July 15, 1978,” by Jo Freeman, and “Native Americans Walk from San Francisco to Washington, D.C. for U.S. Civil Rights, 1978” at Global Nonviolence Action Database.

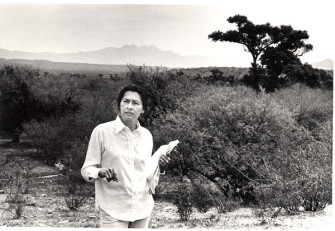

Carolina Butler, an opponent of Orme Dam and activist, played a key role in defeating the project. Image: AZ PBS.

1981: Fort McDowell Yavapai Nation Celebrates the Orme Dam Victory

After 10 years of organizing and protesting the building of the Orme Dam, on November 12, 1981, the Fort McDowell Yavapai Nation of Arizona won the struggle when Interior Secretary James Watt announced that Orme Dam would not be built. The dam was a Central Arizona Project plan that would have flooded more than half the Fort McDowell Yavapai Nation reservation, most of their farmland, and the remnants of ancestral homeland. Each year, a weekend long celebration is held called the Orme Dam Victory Days to commemorate the event.

Learn more about this struggle and background in the articles, “Orme Dam and the Yavapai; A Broken Promise Could Break a Nation,” by Christina Ravashiere in the Christian Science Monitor.

Watch a documentary at Arizona PBS.

1992: National Coalition of Racism in Sports and Media Forms

1992: National Coalition of Racism in Sports and Media Forms

In 1992, the National Coalition of Racism in Sports and Media (NCRSM) was established by Native leaders in order to organize against the use of Indian images and names for logos, symbols or mascots in professional and collegiate sports, marketing and the media. While the National Congress of American Indians (NCAI) launched a campaign to address stereotypes found in print and other media in 1968, the NCRSM focused directly on the issue of sports mascots, building on previous decades of work to change team mascots, stating:

These mascots and symbols serve to mis-educate all youth by perpetuating an inaccurate history and encouraging a suspension of logic and reason. Schools, teachers and students become culturally illiterate in the realm of Native history and culturally insensitive with respect to teaching tolerance and celebrating diversity.

Learn more about the long history of mascot and name changes by schools, cities, and sports team, including Washington, D.C.’s NFL team. Listen to a StoryCorps interview with D.C. teacher Julian Hipkins about the controversy.

2004: Coalition Forms to “Protect the Peaks”

On, February 2, 2004, the Save the Peaks Coalition formed to address environmental and human rights concerns with Arizona Snowbowl’s proposed developments on the San Francisco Peaks, land that has spiritual and cultural significance to at least 13 surrounding tribes. This coalition (made up of tribal and spiritual leaders, citizens, agencies, business, and conservationists) rallied to protest the “clearcutting of approximately 30,000 trees, that is home to threatened species, making new runs and lifts, more parking lots, and building a 14.8 mile buried pipeline to transport up to 180 million gallons (per season) of wastewater to make artificial snow on 205 acres.” Despite decades of protest, the U.S. Forest Service and other government agencies have permitted the Snow Bowl ski resort to expand, the coalition continues to protest with calls to boycott the ski resort.

Learn more at: www.protectthepeaks.org/about/ and watch the documentary, The Snowbowl Effect, by Native activist Klee Bennally.

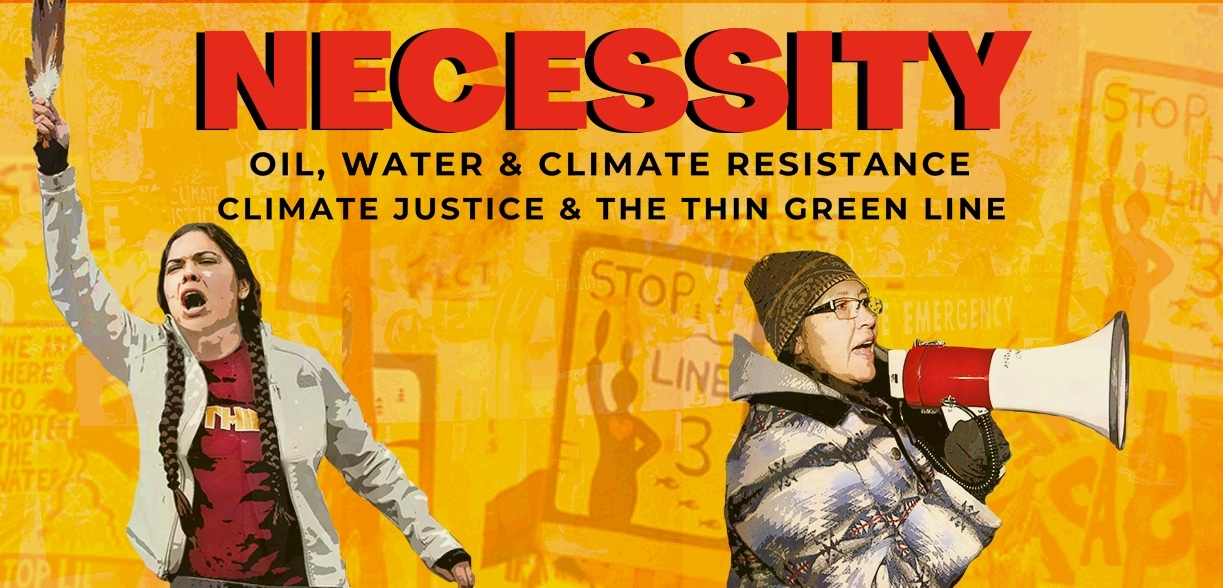

2011: Keystone XL Pipeline Protesters Launch Massive Campaign

In August 2011, environmental and indigenous groups launched a massive campaign designed to press President Obama not to approve Phase IV of the Keystone XL Pipeline project that would run through and near tribal lands, water resources, and place of spiritual significance. On Nov. 6, 2015, President Obama rejected the Keystone XL Pipeline proposal. The Indigenous Environmental Network, representing several indigenous groups and nations, issued a press release by Tom Goldtooth, executive director, stating:

In the fight against Keystone XL our efforts as Indigenous peoples, whether Lakota, Dakota, Assiniboine, Ponca, Cree, Dene or other has always been in the defense of Mother Earth and the sacredness of the water. Today, with this decision we feel those efforts have been validated. With the rejection of Keystone XL we have not only protected the sacredness of the land and water we have also helped our Cree & Dene relatives at the source take one step closer to shutting down the tar sands. The black snake, Keystone XL, has been defeated and best believe we will dance to our victory!

Explore this issue with students in the teaching activity, “Dirty Oil and Shovel-Ready Jobs: A Role Play on Tar Sands and the Keystone XL Pipeline” by Abby MacPhail. And have students learn about Indigenous Peoples’ activism to respond to climate change in “‘Don’t Take Our Voices Away’: A Role Play on the Indigenous Peoples’ Summit on Climate Change,” by Julie O’Neill and Tim Swinehart.

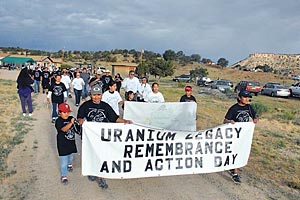

2013: Havasupai Tribe Files a Lawsuit to Stop the Operation of a Uranium Mine

On March 7, 2013, the Havasupai Tribe, along with three conservation groups, filed a lawsuit against the U.S. Forest Service “over its decision to allow Energy Fuels Resources, Inc. to begin operating a uranium mine near Grand Canyon National Park without initiating or completing formal tribal consultations and without updating an outdated 1986 federal environmental review.” In April 2015, a U.S. District Judge ruled on this suit and decided uranium mining can continue in Northern Arizona.

Uranium mining on and near tribal and ceremonial lands, as well as being in close proximity to the Grand Canyon, has raised concerns of tribal rights, environmental impact, and safety issues for decades. On Oct. 12, 2015, in collaboration with Havasupai, Hualapai, Hopi, Navajo, Zuni, Paiute, and Yavapai leaders, Arizona Congressman Raúl Grijalva announced a bill designed to permanently ban uranium mining in the Grand Canyon watershed. As reported in the Phoenix New Times:

According to a statement from Grijalva’s office, the bill, if successful, “permanently protects the Grand Canyon from new uranium mining claims; protects tribal sacred cultural sites; promotes a more collaborative regional approach between tribal nations and federal land managers; protects commercial and recreational hunting; preserves grazing and water rights; and conserves the Grand Canyon watershed.”

Read more about the struggle in, “Uranium Mine Near Grand Canyon Approved by Federal Judge,” by Miriam Wasser and about Clean Up the Mines!, a concurrent campaign to clean up thousands of abandoned uranium mines throughout the U.S. Watch an interview with activist Klee Bennally on Democracy Now!

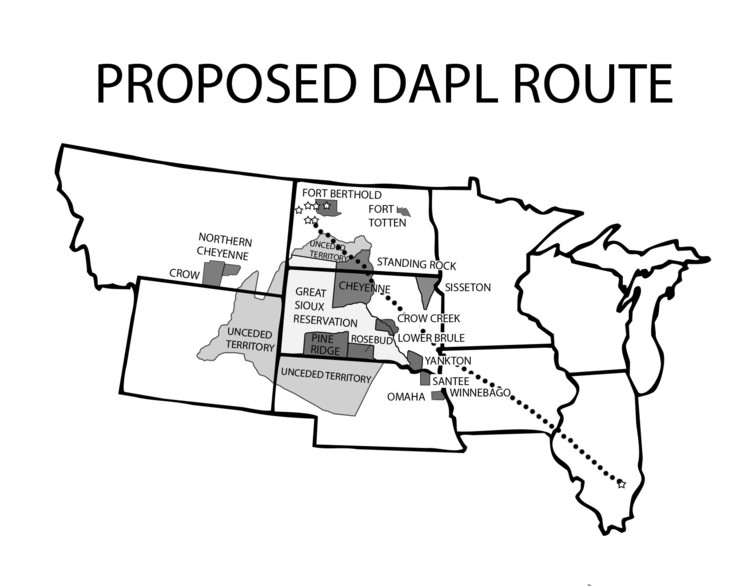

2016: Standing Rock Sioux Oppose the Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL)

On April 1, 2016, one of the greatest organizing efforts to protect land, human rights, and the future of this planet began in North Dakota.

As described in the DAPL Fact Zine,

Images: Sacred Stone Camp/#NoDAPL

On April 1st, 2016, tribal citizens of the Standing Rock Lakota Nation and ally Lakota, Nakota, & Dakota citizens, under the group name “Chante tin’sa kinanzi Po” founded a Spirit Camp along the proposed route of the bakken oil pipeline, Dakota Access. The Spirit Camp is dedicated to stopping and raising awareness the Dakota Access pipeline, the dangers associated with pipeline spills and the necessity to protect the water resources of the Missouri river.

The Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL) is proposed to transport 450,000 barrels per day of Bakken crude oil (which is fracked and highly volatile) from the lands of North Dakota to Patoka, Illinois. The threats this pipeline poses to the environment, human health and human rights are strikingly similar to those posed by the Keystone XL. Because the DAPL will cross over the Ogallala Aquifer (one of the largest aquifers in the world) and under the Missouri River twice (the longest river in the United States), the possible contamination of these water sources makes the Dakota Access pipeline a national threat.

The Standing Rock Sioux have been joined by members of more than 200 other Native American tribes and allies in taking a stand against the Dakota Access Pipeline. Learn more at Sacred Stone Camp website and stay up to date on news at Democracy Now!

© 2016 Zinn Education Project

2018: Ancestral Land Returned to Ponca Tribe

On June 10, 2018, along the “Trail of Tears” in Neligh, Nebraska, a farmer signed a deed to return ancestral land to the Ponca Tribe. Nearby is the gravesite of White Buffalo Girl, an 18-month-old Ponca girl who died during the forced removal of the Ponca Nation.

In 1877, the Ponca Nation was forced by the federal government to leave their home of Nishu’de ke (also known as Missouri) to relocate 600 miles south into present-day Oklahoma. Their forced removal took 55 days and killed several — including White Buffalo Girl — and is known as the Ponca Trail of Tears.

In 2013, farmer Art Tanderup retired on his wife’s farm just outside of Neligh, when they found out that the Keystone XL Pipeline would be built right across their property. Tanderup and others formed a coalition between farmers, ranchers, and Native peoples called Bold Nebraska that opposed this decision. At one of the events held by this coalition, Tanderup met Mekasi Horinek, a member of the Ponca Nation. Mekasi shared with Tanderup that his grandfather had walked through his farm as an eight-year-old boy during this forced relocation.

During their discussion, Horinek explained that the relocation had been especially brutal because they were forced to leave all of the corn they had harvested that year behind. Tanderup and Horinek decided to plant corn in the middle of the Keystone Pipeline’s proposed route.

Horinek tracked down corn that had come from the final crop planted by the Ponca, which had been saved in medicine bundles by the Lakota. With just two handfuls of sacred red corn, they planted the 137 year old kernels. The first harvest in 2014 was wildly successful, and the ceremonial plantings and harvests have now become an annual event for both the Ponca Nation and non-Ponca people alike. Tanderup and his family formally deeded a portion of his farm to the Ponca Nation, saying that he wanted to make the first steps towards righting the wrongs of their ancestors. Continue reading in this This Day in History post.

Recommended Article

The Spirit of Standing Rock on the Move by Stephanie Woodard, YES! Magazine, Winter 2017.

The Spirit of Standing Rock on the Move by Stephanie Woodard, YES! Magazine, Winter 2017.

People from more than 300 tribes traveled to the North Dakota plains to pray and march in solidarity with the Standing Rock Sioux. Back home, each tribe faces its own version of the “black snake” and a centuries-old struggle to survive. [Publisher’s description]

My father Gregory F. Zephier Sr. was a Native American Activist and we participated in many of the above, movements, today a New Longest Walk 5 War on Drugs and Domestic Violence, lead by Mr. Dennis Banks still going. To combat the Heroin and Meth problem and the Domestic Violence against Native Women!

Nice compilation, thank you!!

A great historical piece! More people should be made aware of this! Nevertheless, I never celebrated/celebrate the holiday for the reason it was first established. I celebrate being thankful to GOD for all of the BLESSINGS that HE has bestowed upon me during the past/last year! That is what Thanksgiving means to me….. I will be sharing……….

These are a treasure. Thank you.