Howard Zinn taught at Spelman College and Boston University where he had an extraordinary influence on his students’ understanding of history and their role in the world. This series highlights Zinn’s lasting impact as a professor. Read more stories and submit your own.

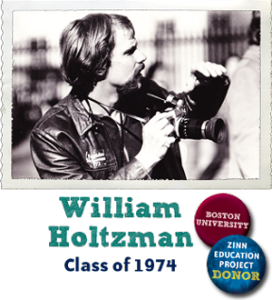

Below is the entry from William Holtzman, class of 1974.

William Holtzman, BU Class of 1974

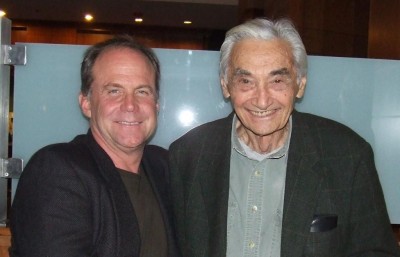

What can I say about my friend Howard Zinn? I met Howard at Boston University, where I attended his classes in the mid-1970s.

To this day, I can quote chapter and verse from his lectures. The man could be spellbinding in a gentle, whimsical way.

One lecture stands out because it says so much about Howard. It was the last lecture of the semester, and he said, “Enough of me; let’s turn it over to you. Let’s talk about whatever you want to talk about.” His lecture attracted 500-plus students, so I was quick to hold up my hand.

I liked to challenge Howard, so I gave it my best shot: “Howard, we just finished an entire semester on American politics, but we’ve never talked about compromise, and compromise is fundamental to the American system. Could you talk about the fine art of compromise and tenure?”

With his Buddha-like manner, he nodded and said: “So, you want to know what I compromised for tenure? Is that the question?” Essentially, that was the question.

“Well, I have a funny story about that. When I was nominated for tenure in the mid-1960s, the rules at BU were pretty simple. If the political science department voted to extend tenure, the rest of the bureaucracy would rubber-stamp it.”

The department finally voted, and it was tied. A second vote gave Howard a one-vote majority, so he was now on the fast track for tenure. And said tenure would be confirmed at the annual Founders Day banquet. But that event was still months away.

Around the same time, a few students asked him to speak at an anti-Vietnam War rally at Copley Plaza in downtown Boston. Howard immediately said yes but didn’t ask for any details.

Around the same time, a few students asked him to speak at an anti-Vietnam War rally at Copley Plaza in downtown Boston. Howard immediately said yes but didn’t ask for any details.

Make no mistake, the Vietnam War enjoyed wide public support in the mid-1960s, and dissenters were considered traitors, communists, or both. This didn’t deter Howard for a second.

He finally realized the anti-war protest was focused on Dean Rusk, President Lyndon Johnson’s secretary of state. And why was Rusk in Boston? To speak at BU’s annual Founders Day banquet.

Howard picks it up from there: “Well, I slowly figured out my academic future was in serious jeopardy.” Speech day/tenure day finally came, and Howard arrived at Copley Plaza and asked who else was speaking. “Well, we’ve had a lot of cancellations, Howard, so you’re it. . .can you stretch your talk to 45 minutes or longer?”

At that point, Howard knew his goose was cooked, so, in his words, he decided to go all out. “I was in great form that day. I denounced the war, I denounced the secretary of state, the president. . . . I even denounced the founders.”

The crème de la crème of polite Boston society, the BU trustees, turned up in black tie to discover one of their own at a microphone loudly denouncing anything and everything.

Howard went back to campus and began to think about his next teaching assignment — in another state or another country.

Howard went back to campus and began to think about his next teaching assignment — in another state or another country.

A few days later, a certified letter arrived from the Board of Trustees. It read something like: “Dear Dr. Zinn: Congratulations, the board has extended tenure” — on the morning of the annual Founders Day event.

To me, this was vintage Howard Zinn: honest, courageous, and right on target.

William Holtzman co-founded the Zinn Education Project with Howard Zinn.

This letter was originally published in the San Francisco Chronicle on January 30, 2010.

|

|

|

|

|

|