By Bill Bigelow

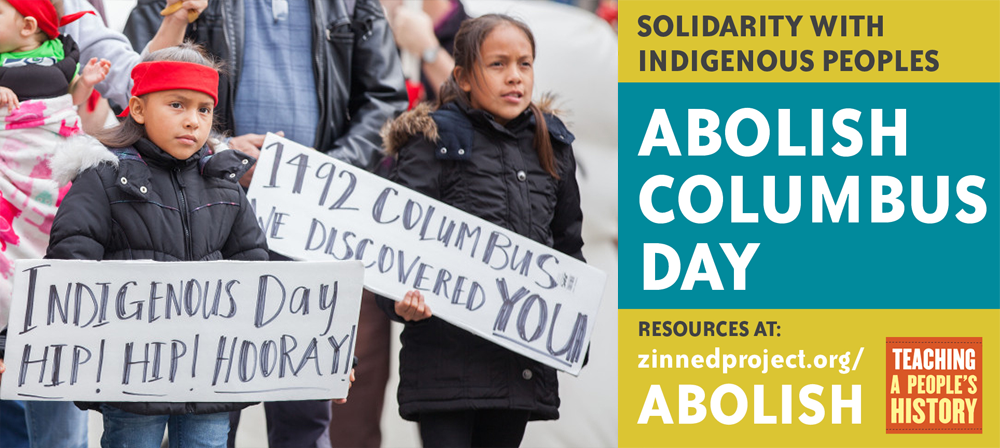

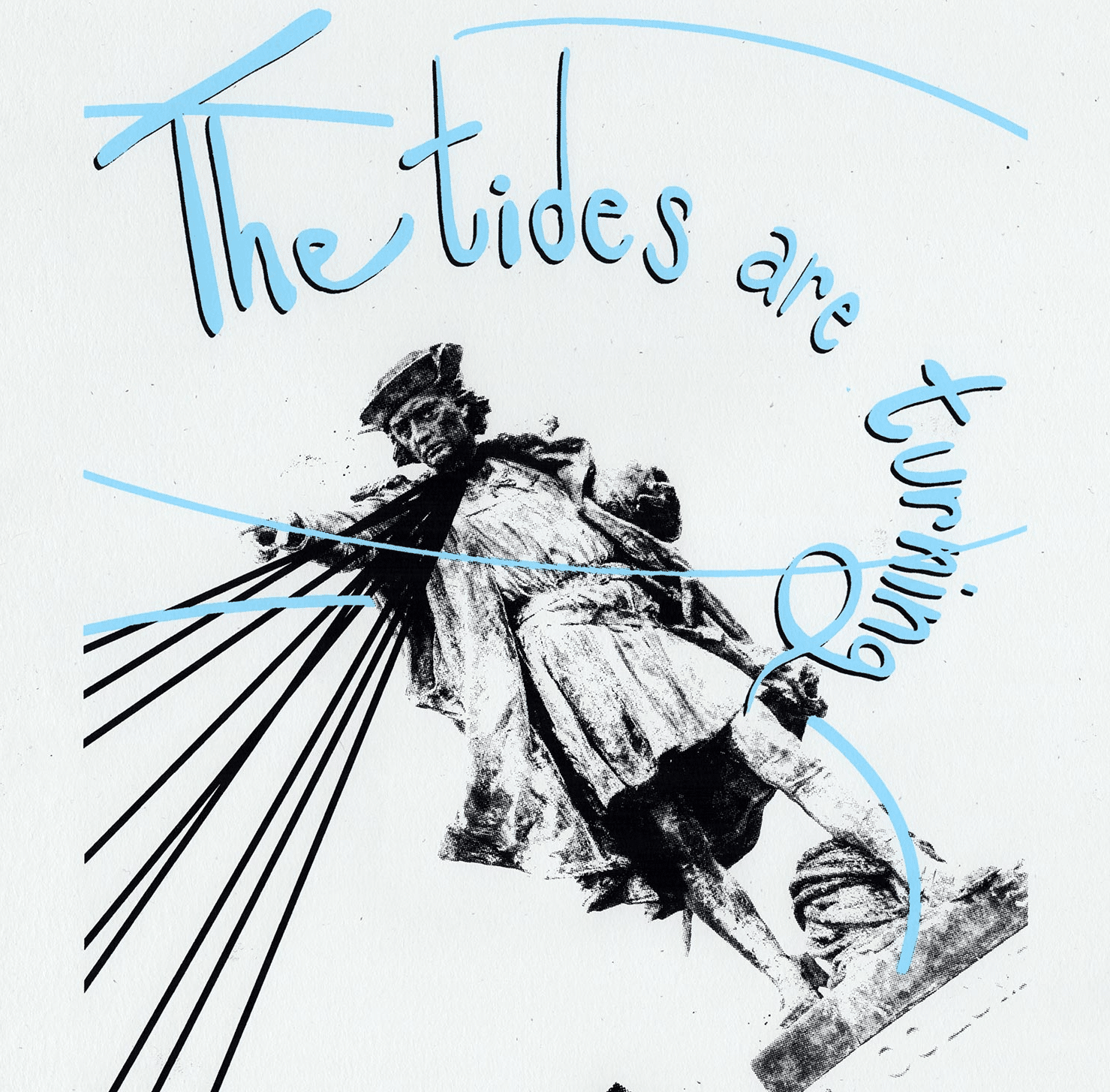

The movement to abolish Columbus Day and to establish in its place Indigenous Peoples’ Day continues to gather strength, as every month new school districts and colleges take action. This campaign has been given new momentum as Indigenous peoples throughout the Americas assert their treaty and human rights. Especially notable is the inspiring struggle in North Dakota to stop the toxic Dakota Access Pipeline, led by the Standing Rock Sioux.

Dave Archambault, chairperson of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe, explains that the oil pipeline “is threatening the lives of people, lives of my tribe, as well as millions down the river. It threatens the ancestral sites that are significant to our tribe. And we never had an opportunity to express our concerns. This is a corporation that is coming forward and just bulldozing through without any concern for tribes.”

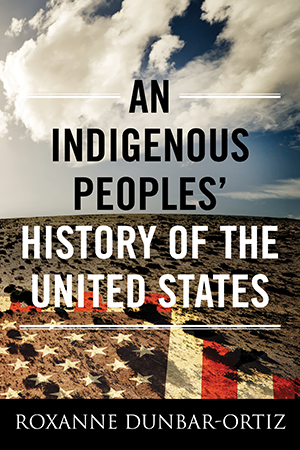

The “bulldozing” of Indigenous lives, Indigenous lands, and Indigenous rights all began with Columbus’s invasion in 1492. Columbus’s policies toward Indigenous peoples in the Caribbean were genocidal. On the island that became Haiti and the Dominican Republic, Columbus ordered Taíno people’s hands chopped off if they did not deliver sufficient quantities of gold. His men took women and girls as sex slaves. He had Taínos chased down by vicious dogs. He ordered his men to “spread terror” among Taínos who resisted — and they did resist. And he launched the transatlantic slave trade — from the Americas to Europe, as well as from Africa to the Americas. “Let us in the name of the Holy Trinity go on sending all the slaves that can be sold,” he wrote.

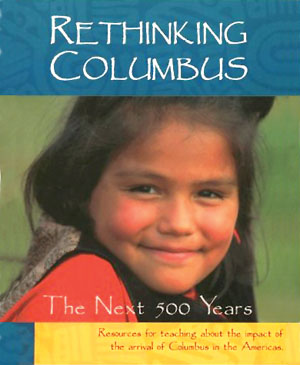

Through the conventional story of the “discovery of America,” the school curriculum has taught students to celebrate colonialism and racism, and to disregard the lives of the Taínos, and other Indigenous peoples. The Columbus-discovers-America story has long been a kind of secular book of Genesis — “In the beginning there was Columbus . . .” — the original Only White Lives Matter myth. And it has played a central role in the curricular erasure of the humanity of Indigenous peoples.

Through the conventional story of the “discovery of America,” the school curriculum has taught students to celebrate colonialism and racism, and to disregard the lives of the Taínos, and other Indigenous peoples. The Columbus-discovers-America story has long been a kind of secular book of Genesis — “In the beginning there was Columbus . . .” — the original Only White Lives Matter myth. And it has played a central role in the curricular erasure of the humanity of Indigenous peoples.

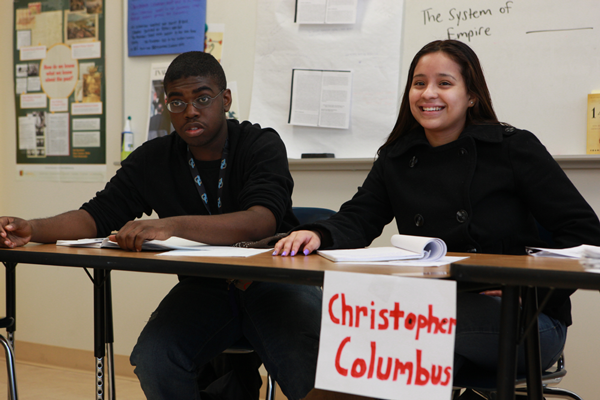

I taught high school social studies for almost 30 years. One of my first activities in my high school U.S. history classes was to steal a student’s purse. Yes, I wanted to capture students’ attention at the beginning of the school year, but I also wanted them to think about whose lives are valued — and whose aren’t — in the traditional curriculum.

I began by loudly calling for everyone to watch carefully, and then I’d snatch a purse off a student’s desk. Frankly, purses worked better than backpacks, because they are more personal, and my theft seemed more, well, invasive.

Bigelow “discovers” a student’s purse in the 1992 film, “The Columbus Controversy.”

“This is my purse,” I would announce to looks of disbelief and annoyance. But annoyance turned to outrage when I opened the purse and started taking things out. (The student who owned this purse, let’s call her Maria, knew what was coming, and had agreed to it, but I’d alerted no one else.) “This is my comb. This is my pen. This is my lipstick.” And when students protested, I demanded that they prove that the purse was Maria’s and not mine. “That’s her stuff in there.” “We saw you take it.” “She knows everything that’s in there, and you don’t.”

“Alright, alright. Then let’s say I discovered the purse. That makes it mine, right?”

Students quickly saw where I was going, as we compared my purse-stealing to Columbus’s “discovery”: The people who were here first — the Taínos — had “stuff” in their land, they had lived there a long time, they knew the land better than Columbus, etc. “So why do some people call it discovery? Why don’t we use the same language that you used to describe what I did to Maria’s purse? Columbus stole the Taínos’ land. He ripped it off. And because he came armed, he invaded it.”

At the heart of all our schooling is a narrative about whose lives matter—who counts in the world. Even today, if I stand in front of a class of high school students and start rhyming, “In Fourteen Hundred and Ninety-Two . . .,” large numbers of students will finish with “. . . Columbus sailed the Ocean blue.” But few of them know the name of the people who were here when Columbus arrived — the Taínos. This tells us that too often our schools still teach young people to celebrate Great White Men and disregard the lives of the “discovered” and dominated.

At the heart of all our schooling is a narrative about whose lives matter—who counts in the world. Even today, if I stand in front of a class of high school students and start rhyming, “In Fourteen Hundred and Ninety-Two . . .,” large numbers of students will finish with “. . . Columbus sailed the Ocean blue.” But few of them know the name of the people who were here when Columbus arrived — the Taínos. This tells us that too often our schools still teach young people to celebrate Great White Men and disregard the lives of the “discovered” and dominated.

The Uruguayan writer, Eduardo Galeano, used the term los nadies, the nobodies. Nobodies can be ignored and ruled, removed and slaughtered, without consequence. They are people who don’t matter:

Who don’t speak languages, but dialects.

Who don’t have religions, but superstitions.

Who don’t create art, but handicrafts.

Who don’t have culture, but folklore.

Who are not human beings, but human resources.

Who do not have faces, but arms.

“With 50 men we can subjugate them all and make them do whatever we want,” Columbus boasted in his journal about the Taínos — los nadies, the nobodies — on just his third day in the Americas.

This disregard for the lives and rights of Indigenous peoples has long been mimicked in the school curriculum, and so often it begins with the Columbus-discovers-America myth. Students readily learn whose lives matter and whose don’t. Whose lives are they invited to imagine? Whose stories are featured in history classes and the literature read in the language arts curriculum?

The good news is that this is changing. The Black Lives Matter movement has denounced our society’s failure to value all lives equally — challenged the continuous war waged especially on Black men, but on people of color more broadly. And high school students, educators, and communities of color are winning demands for more ethnic studies in the schools — curriculum that interrogates racial inequality and features historic struggles to make society more equal.

And that brings us back to Columbus Day. If we are sincere in our claim that all lives have value, then schools need to refuse to honor the first European colonialist of the Americas, the “father of the slave trade.” This is not about what went on 500 years ago. It’s about what’s going on today: an inspiring struggle for rights and dignity. We need to begin to see Indigenous peoples — in the world and in the curriculum.

This article is part of the Zinn Education Project’s If We Knew Our History series.

This article is part of the Zinn Education Project’s If We Knew Our History series.

Posted on: Common Dreams | Alternet.

© 2016 The Zinn Education Project, a project of Rethinking Schools and Teaching for Change.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn