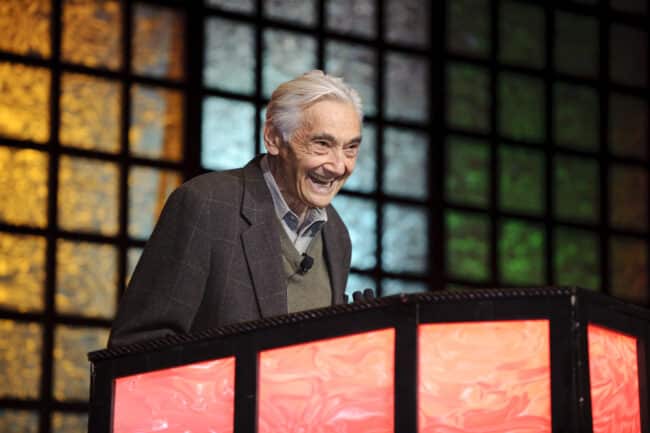

Howard Zinn gave a keynote speech to more than 800 teachers at the National Council for the Social Studies Conference in Houston on November 16, 2008.

He addressed key issues in history and current events including:

- Academics and Activism

- Thinking Outside of the Box

- Conflicting Interests Throughout U.S. History

- American Exceptionalism

- Patriotism

- Military Power and National Security

- Who Makes History?

- People Can Change

The formal talk was followed by questions and answers.

Viewed in full or in sections, it is an excellent presentation for teacher workshops or discussion groups.

Below is a slightly edited transcript of speech. It is edited for ease of reading; none of the content is changed. The times are included on the transcript so that anyone using the film can select excerpts. The film and transcript are shared here with permission of the National Council for the Social Studies.

00:00:00 Howard Zinn: Thank you, thank you. Can you hear me OK? OK. When you speak you like to be heard.

00:00:32 I’m happy to be talking to social studies teachers. I admire you a lot. Mainly because you’re teaching middle school and high school, and I always thought that middle school teachers and high school teachers are the most heroic people. Really, you know, I compare you to the kind of jobs I had and the kind of jobs we — I hope the university teachers who are here are not offended by what I say — but the fact is, I don’t think we work as hard as you do.

00:01:04 This is recorded for posterity, and it’s a bad thing to say. It will result in decreasing the salaries of university teachers, but maybe it will result in increasing your salaries, which will make up for it. And you need it more, yes.

Howard Zinn offering keynote at 2008 NCSS Conference in Houston, TX. Photo by Steve Puppe.

Academics and Activism

00:01:28 So, I start from a premise that we’re teaching social studies not just because we want to prepare our students to get high grades on exams and — and do well in the Bush program of Leave No Child Behind, which is a slogan he stole from a former student of mine, Marian Wright Edelman, who’s head of the Children’s Defense Fund in Washington. Their slogan has been “leave no child behind” and, I know it’s an accusation about stealing a slogan, but you know, it’s a good slogan.

00:02:13 But I don’t think we teach in order to prepare people for exams. In order simply for them become quote successful and make their way in society and become sort of another little cog in society’s machinery. Not that we want our students to starve, yes of course, everybody has to make a living and so on.

00:02:42 But it seems to me that people who teach social studies want something more than that. They want it that young people should come out of their classes, I think, you know, imbued with desire to change the world. A modest little aim, right? That’s what we want.

I was struck by something Barack Obama said. How many people here are happy that Barack Obama — well — yeah.

00:03:26 That’s known as a scientific poll. A scientific poll is where you just ask one side of the question, you don’t ask how many people are unhappy. OK, now it’s scientific.

00:03:46 But I was struck by one thing Obama said in the course of the presidential campaign, and you may remember this. At one point he said, “I want us not to just get out of the war in Iraq, but I want us to get out of the mindset that brought us into the war in Iraq.” And this struck me as something very important. As teachers, it seems to me, that is what we want to do — encounter and deal with, not just immediate circumstances and not such — superficial issues, but mindsets.

00:04:32 That is, ideas that are deeply ingrained by our culture, and that we need to challenge. And so, I want to talk for a while about that, then later I want to come back and see if — if Obama has followed his own instruction to challenge that mindset, which is a delicate matter.

Thinking Outside of the Box

00:04:59 But I can’t think of anything more important we can do in education than to get students to challenge these fundamental premises which keep us inside a certain box. We want people to think outside of that, because if they don’t things will never change.

00:05:26 If they don’t think outside that box, if they don’t challenge the premises, then we’ll go on as we have been going on, and then we’ll have the kind of world that we have had so far, which is not good enough, right? A world of war and hunger and disease and inequality and racism and sexism. We want to move away from that and so we have to re-examine these premises.

Conflicting Interests Throughout U.S. History

00:05:59 One of these is the idea that we all have a common interest. Everyone in society, that we’re one big happy family. That’s like the first words of the preamble to the Constitution: “We the people of the United States.” But of course, we know it wasn’t “we the people of the United States” who established the Constitution. It was 55 rich white men in Philadelphia who established the Constitution.

00:06:32 And the American Revolution was not fought by we the people, by all the people. No, no, there was a lot of dissent and disagreement, and there were soldiers’ mutinies. When the Constitution was finally adopted it was only adopted in reaction to rebellions of farmers in western Massachusetts who saw the rich in Boston taxing them so heavily and many of these [were] veterans of the Revolutionary War.

00:07:01 There was class conflict before the revolution, during the revolution, after the revolution, and represented, finally, by a constitution which was set up to favor the interests of the upper classes. After all, you know, the Constitution established the rule of slaveholders and merchants and bond holders. It had elements of democracy, it had some elements of representative government, but my point is it was a class document.

00:07:30 They didn’t all have the same interests. And all through American history we have not had the same interests. We have had people on the top, and we’ve had people on the bottom, and in between we’ve had a lot of nervous people. So after all, the important thing for young people to think about so they don’t simply swallow these enveloping phrases like “the national interest,” “national security,” “national defense,” as is if we’re all in the same boat.

00:08:09 No, the soldier who is sent to Iraq does not have the same interests as the president who sends him to Iraq. The person who works on the assembly line at General Motors does not have the same interest as the CEO of General Motors. No — we’re a country of divided interests, and it’s important for people to know that.

00:08:28 It’s important for people to know their own interest and not confuse their interest with the interests of the people up on high. Because people up on high, of course, in order to stay up on high have to persuade the people below them that they all have the same interests. They don’t. The language, the culture, lends itself to this idea of we all have the same interests of national security.

00:08:59 No. And for some people, a small number, national security means military strength. I would say that for most people, national security means having a job, having health care, just having a decent standard of living. Different definitions of security. So, that’s one kind of premise that needs to be examined.

American Exceptionalism

00:09:29 Another one that we all grow up with is the premise that the United States is somehow unique in the world. Well, of course every place is unique and every country is unique. That’s not the point. But unique, not just unique, but better. The best. Number one. We are the greatest, right?

00:10:00 That is a dangerous thing to think. Because when you begin to think that arrogantly that somehow the United States is an exception to the things that plague other countries and other governments in the world, that is dangerous for people — it’s dangerous for people in other countries. And it’s dangerous for people in our country to think that way. That kind of arrogance leads to trouble.

00:10:30 You know, in the world of social science, that notion, that premise is called “American exceptionalism.” I think that’s something that young people need to re-examine. I think that we need to have an honest view of our country. Not in order to put it down, but to see it in the context of countries in the world. That’s where history comes in handy.

00:10:57 For instance, if you look at the history of American expansion in the world, we have expanded, haven’t we? Yeah, we’ve expanded. We were just a thin band of colonies along the east coast and we expanded across the continent. And I remember when I went to school it all seemed very benign. The Louisiana Purchase, it was empty. It was a huge, huge, huge tract of empty land, you know.

00:11:33 Much later it suddenly struck me, hey, there were people living there. There were Indigenous people there, hundreds of tribes there. We had to get rid of them in order for it to be ours, in order for our railroads to crisscross that land, and for our corporations to move into that land. But, we were an expansionist country from the beginning. There’s the Louisiana Purchase, there’s the Mexican cession – I like that word “cession”.

00:11:59 They just ceded it to us. They’re friendly people. No, we fought a war with Mexico and then we took almost half of their land. And now we build a wall along the southern [border] to keep them out of the land we took from them. It’s really neat, yes.

Expansionism. And then we expand – and you know this history – we expanded to the Caribbean, with Cuba, and Puerto Rico, and we expanded into the Pacific with Hawaii and the Philippines.

00:12:32 And of course after World War II, you know. And now we have military bases in a hundred countries. So you can’t really say that the United States is different in a good way; that we’re different because we spread democracy and liberty around the world. Because if you look at the history of what happened in those countries that we spread to and occupied, we did not bring liberty and democracy to these places where we fought wars and conquered.

00:13:08 The reason for people knowing this history is so that – again, not to derogate our country, not to be sour; but to say: “Oh, yes, we’re an empire like other empires. There was a British empire, and there was a Dutch empire, and there was a Spanish empire, and yes, and we are an American empire.”

00:13:41 Let’s face it. We’re prone to all the same things that other empires have been prone to, and that is to take advantage of other people and to beat them down when they rebel. So when some leader come and says, “Well, you know, the United States – we go around and we spread democracy and liberty, and tomorrow we’re going to go into this place and we’re going to spread democracy and liberty there.”

00:14:07 Well, that’s where it’s important for young people to know their history. So they’ll say “now wait awhile, let’s be honest about ourselves, and let’s not rush into this, uh, on the ground that we [are] beneficent in everything we do, and we take care of other people in the world.” Of course, when you talk this way it’s just a matter of being honest about yourself, and all of us as individuals need to be honest about ourselves as individuals, you’re — very often you’re accused of being unpatriotic.

Patriotism

And there’s another premise I think that needs to be examined. Another mindset, that needs to be looked at, and that is the whole issue of patriotism. And I think it’s very bad for everybody when young people grow up thinking that patriotism means obedience to your government.

00:15:13 So, if you criticize your government, you’re considered unpatriotic. That premise should be discarded. That’s why it’s important for young people, for all of us, to learn to think about our patriotism; to look at Mark Twain’s definition of patriotism. Mark Twain distinguished between the country and the government.

00:15:43 So, when you hear a young person going off to war saying “I’m doing this for my country,” wait a while. Are you doing this for your country? Are you going off to fight and kill for your country, or are you doing it for your government? That’s different. Or are you doing it for Halliburton, which is even more different?

00:16:00 Patriotism requires a distinction between government and country, that’s what the Declaration of Independence was all about. The Declaration of Independence, which isn’t taught very well, I must say. On the fourth of July you’ll see newspapers printing the whole Declaration of Independence, but it seems meaningless because they don’t really catch the philosophy of the declaration because the philosophy of the declaration is expressed in the idea that governments are artificial creations.

00:16:41 They’re set up by the people to ensure certain rights, an equal right to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness. And, according to the declaration, when governments become destructive of these rights, it is the right of the people to alter or abolish the government. There’s the government and there’s the people. There’s the government and there’s the country.

00:17:05 Patriotism does not mean support of government. Patriotism means support of the principles of the government it’s supposed to stand for. And when the government violates those principles, well, you might say the government is being unpatriotic.

So that premise of patriotism needs to be examined.

Military Power and National Security

00:17:32 Another mindset which is very important to discard is the mindset that believes that military power is what keeps you safe. And war defends you, even if you’ve sent your troops half way around the world to invade a little country, a country that has been beset itself by wars and civil wars, whether it’s Afghanistan, or Iraq.

00:18:12 Even if you send your armies halfway around the world to invade and bomb and attack this little country, you know, that somehow you’re doing it for “defense.” That’s another word that needs to be examined, the word defense. When are you really defending yourself, and when are you not? The idea that military force protects you is something that needs to be re-examined.

00:18:44 A few weeks ago I was doing a phone interview with a radio station. I do a lot of interviews by phone because it’s easy. I can sit home in my pajamas, or without my pajamas, and be interviewed by a radio station in Missoula, Montana, or wherever. You see, it’s very nice. But I was doing this thing and then there were call-ins, and then this person called in and because I’d said something really bad.

00:19:19 I had talked about dismantling American military bases around the world. Now you can see how troublesome a statement like that would be. It attacks a very fundamental premise that we, you know, that’s how we defend ourselves. We need military bases all over the world. This person said “How can we defend ourselves against terrorism if we don’t have these military bases?” I said (I like to quote myself, I find I’m always right) I said, “Think about this.”

00:20:02 At the time 9/11 took place we had military bases in a hundred countries in the world. At the time 9/11 took place, we had 10,000 nuclear weapons. We had aircraft carriers and battleships on every sea in the world, and we were attacked by terrorists. So, how does military strength protect us against terrorism? These aircraft carriers that we keep building are a billion dollars a carrier, right? A billion dollars a carrier.

00:20:36 How does that protect us against terrorism? How does it protect us against anything, you know? You have to think about that. And in fact, is it possible that the military things that we do, the bases that we have, the invasions that we engage in. Is it possible that they not only do not protect us against terrorism but that they provoke terrorism? Provoke terrorism?

00:21:02 It doesn’t take much thinking to realize that if you station troops in other countries, the people in that country might be annoyed. The governments may accept it because they get, you know, benefits from it and the economic people on top might accept it because they get benefits from it.

00:21:27 But the people very often resent it. People in Okinawa resent all those American bases on Okinawa, people in South Korea, etc. They may resent it. And when you annoy a lot of people in the world with all these bases around them by invading and attacking, you are annoying millions and millions of people. And out of those millions and millions people, a very tiny number of them will become fanatics, terrorists, violent.

00:22:01 So, it may very well be that the military actions that we take, presumably to defend ourselves against terrorism, are exactly what increases the number of terrorists in the world.

And it’s interesting that if you — to put it another way — there are countries that don’t worry about terrorism. There are a lot of countries that they don’t worry about terrorism.

00:22:30 Why? They’re not bothering anybody. If you look at the report, the official report of the commission, the 9/11 commission, it was set up to investigate 9/11, etcetera. And if you look at the inside pages of that report you will find — I don’t know if I have it with me — but, I always claim I have something with me, and then I find I don’t, in which case I make it up.

00:23:01 This is, you know, this is the commission headed by Lee Hamilton. I’m quoting from it: “The presence of American forces in the Middle East was a major motivating factor in Al Qaida’s actions.” And then one of their investigators, the supervising special agent named James Foley, says “There was a sense of outrage against the United States that was behind 9/11.”

00:23:41 So, you know, it’s not just us, you know, the people are – on my radical side, you know, who say that American foreign policy needs to be reexamined if we want to do something about terrorism. Because, when you start talking that way, [they] say “Oh, what? You’re blaming us for 9/11?”

00:24:03 No, it’s not that. They did 9/11, but you know, it’s not an intelligent response to [an] attack on you to then strike out blindly, look for a country you can bomb and say “we’re going after the terrorists”. You don’t know where the terrorists are. Number one, we went into Afghanistan, and most of the country was for it, then there are still people who say “well, the war in Iraq was bad, but the war against – in Afghanistan is good.”

00:24:33 Well, if you look back at what happened at that moment, you know, the country – 9/11 took place, the hijackers, etcetera, kind of hysteria in the country, kind of fear in that atmosphere. Bush, “Oh, we’ve got to attack Afghanistan because we’ve got to go after the hijackers. We have to go after the people who planned it, we have to go after Al Qaida, and Al Qaida is in Afghanistan.”

00:24:57 Well, probably, yes. Al Qaida was in Afghanistan, but where? We didn’t know. Osama Bin Laden is in Afghanistan. Where? We don’t really know. So what will we do? We just bomb Afghanistan. Like, you know, the chief of police can’t find a criminal. We know he’s in this neighborhood. We don’t know where. Bomb the neighborhood. Really, when you think about it, how unintelligent can you be?

00:25:28 So, all these premises about military power and the importance of military power and dealing with problems [with] military power, and defending yourself against terrorism with military power need to be examined. The whole idea of war needs to be examined because if you’re against terrorism; I believe if you’re against terrorism you have to be against war. War is terrorism. You have to just look at it historically.

00:26:04 Especially since World War II, you know, before World War II, in war it was mostly soldiers who died. Like World War I it was ninety percent soldiers, ten percent civilians. By World War II it was fifty percent soldiers, fifty percent civilians. After that, Korea, Vietnam, it’s seventy, eighty percent innocent civilians who die in war, you see.

00:26:30 So I’d argue war needs to be the premise that somehow war can solve problems in the world. That war is necessary. I think that needs to be examined. Not that there aren’t tyrants in the world, not there aren’t situations in the world that call for some sort of remedy. All I’m arguing is the remedy cannot be war, because war is always the indiscriminate killing of huge numbers of people, and that is terrorism.

00:27:07 You can say “well, oh, the terrorists they mean to kill innocent” – I’ve seen this distinction made by very well educated people who I think should know better. They make this distinction: “The terrorists deliberately kill innocent people. When we kill innocent people it’s by accident. It’s inadvertent. They’re collateral damage.”

00:27:30 Well, I don’t accept that. It’s not that we deliberately kill innocent people. It’s just that we engage in actions which inevitably kill innocent people. So, there’s something in between accidental and deliberate, and the word is inevitable. And when you’re doing something that will inevitably have horrific consequences, you mustn’t do it. So, all of that needs to be, I would argue, reexamined.

00:28:05 I said I would come back and look at a question about whether Obama, who made that very profound statement about changing our mindsets reminded me of what Einstein once said.

00:28:45 He once said, “We must change our way of thinking.” Change our mindset. And then I said I’d come back to question. Did Obama change his mindset? Well, in some instance he did, and other instances he did not. He did not change his mindset about military force, and so although he wants to withdraw from Iraq, he wants to send troops to Afghanistan, he wants to build up our military.

00:29:16 He has not gone beyond the premise that military strength is the thing and if you don’t stand for it you’re unpatriotic. Well, you might argue they’re in election campaign he was afraid of being called unpatriotic if he would say those things. I think, unfortunately, it goes deeper than that with him.

00:29:43 I think that we therefore have to face the Obama presidency, honestly and soberly. I mean, I was very happy when Obama won, and I’m still happy that Obama won.

00:30:02 And what a relief. I mean, just, that was to me the word that came to me, relief. We’re through with those . . . whatever they are. War criminals, really, war criminals. Really.

Who Makes History?

So, it’s interesting that Obama himself gave us the clue to being honest about Obama.

00:30:37 Because he said, and this is to his credit, and of course in the campaign, he said, “Don’t count totally on me,” and he was reaching back to his experience as a community organizer, and reaching back to the history of the movement, of the civil rights movement, you know, that don’t depend upon the people up on top.

00:30:59 You the people, you have to do it. Well, that was a very important statement. And it’s very important for us to now to accept that and recognize that so that we don’t look to Obama as a savior, because he won’t, unless we do something to create an atmosphere in which Obama moves out of some of the mindsets that he has, you see.

00:31:29 Like having some sort of belief in a free market and the market system, and capitalism, and bailing out the financial, you know. In order for him to move out of that mindset we have to move out of our mindsets and we have to then become forces and energies that push Obama in a direction that maybe, sort of deep down, I like to think he would want to be pushed.

00:31:58 To counter all of these forces around him, these old timers from the old Democratic establishment, and the Robert Rubins, and the Summers, and the, you know, the Brzezinskis, and the Albrights, and the Clinton retreads who are hanging around him and giving him advice. And he needs a counter to that, he needs the people – all those wonderful enthusiastic people who supported him and traveled from state to state to work for him. That is needed.

00:32:36 I want to tell you about what I think is a very telling quote from Wendell Phillips, and a lot of you know who Wendell Phillips was, he was a great abolitionist leader, uh, [unintelligible] Boston. Wendell Phillips, some of you may know, was a sharp critic of Abraham Lincoln, because Lincoln was not the – I think almost everybody knows this – ending slavery was not Lincoln’s first priority.

00:33:13 And so Lincoln was very political and careful and shrewd and compromising on the issue of slavery, and so the abolitionists, including Wendell Phillips, were very critical of Lincoln. And then Lincoln was elected. And when Lincoln was elected in 1860, Wendell Phillips said this, and this is as close as I can get to quoting to him, because I don’t have his exact quote with me, but this is as close as I can get.

00:33:45 He said “If the telegraph speaks right” – that’s how we learned the news about Lincoln’s election – “If the telegraph speaks right, a slave – the slave has elected the president of the United States.”

00:34:06 And then he said “Lincoln is not an abolitionist. He’s not an anti-slavery man. He’s really a pawn on the chess board. And like a pawn on the chess board he can be moved up, moved up. We could convert him,” Phillips said, “into a knight or a bishop, and into a queen” – queen has, as you chess players know, queen is all — powerful. “Move the pawn, make him a queen, and sweep the board.”

00:34:42 Interesting, that’s the situation. Obama is there on the chess board and he can stay where he is and he could, or Wendell Phillips said, I think I left out a phrase. He said, “With fair effort,” that’s the phrase he used. “With fair effort we can move him across and sweep the board.”

00:35:10 Fair effort. That’s the clue to the rest of us. That effort is needed in order to move Obama and all of us in the country away from that mindset which will keep getting us into war, even if it gets us out of Iraq it will get us into another war.

00:35:30 That mindset which will not solve the economic crisis because it won’t get to the root, the economic system’s root which, I think the root is really capitalism. The root is the profit motive. The root is corporate power, you know, much more serious problem than simply giving a handout to banks and fooling around at the edges of the economic system.

00:36:03 Yeah, we need a new peoples’ movement. We need the kind of movement we had. And we know from the past that we cannot depend on saviors. We can’t depend, they couldn’t depend on Lincoln. They had to have a huge anti-slavery movement that pushed Lincoln into the emancipation proclamation. That pushed Congress into the thirteen and fourteenth and fifteenth amendments.

View this post on Instagram

00:36:28 We’ve never had our injustices rectified from the top, from the president or Congress, or the Supreme Court, no matter what we learned in junior high school about how we have three branches of government, and we have checks and balances, and what a lovely system. No. The changes, important changes that we’ve had in history, have not come from those three branches of government. They have reacted to social movements.

00:36:57 Lincoln and Congress reacted to the anti-slavery movement. Congress and the president reacted to the labor movement. Roosevelt, FDR, reacted to the strikes and the tenants’ movements, and the unemployed councils, and so on. In the civil rights years Johnson and Kennedy, they were not saviors. They reacted to all those people, Black people and some white people in the south who demonstrated and protested and went to jail, and some that were killed.

00:37:31 That’s what they, then got the Civil Rights Act of ‘64 and the Voting Rights act of ‘65. No saviors from the top, [that had never done], always taken, peoples’ movement.

And therefore it’s important, and I think for instance in teaching, to get away from the traditional heroes, there’s another mindset issue. The mindset about who are our heroes.

00:37:59 And generally, as I remember, and I don’t know to what extent, you know better than I do, to what extent this is still the way things are taught, the heroes are military heroes. When you look at the statue, right – the statues on our city squares are statues of military heroes, you see. I think we ought to examine that premise that our great heroes are military heroes in war and look at other heroes.

00:38:28 Young people, yes, young people want icons and they want people they can admire and respect and look up to, and so military heroes fill the bill. But there are other heroes that young people can look up to. And they can look up people who are against war. They can have Mark Twain as a hero who spoke out against the Philippines war. They can have Helen Keller as a hero who spoke out against World War I, and Emma Goldman as a hero. They can have Fannie Lou Hamer as a hero, and Bob Moses as a hero, the people in the Civil Rights Movement — they are heroes.

00:39:02 They can have Ron Kovic as a hero, the Vietnam veteran who came back and opposed the war. We have so many heroes. There’s Muhammad Ali who refused to fight in Vietnam. How better a hero can you have than him?

So they’re there. I think there are ways of satisfying the young peoples’ need for, icons for models. People who protested and people who fought for equality and justice and won.

00:39:36 Sure, there’s a lot of losses in history, but also victories. And have to point to those victories because the victories show that the people up on top don’t simply have absolute power because their power depends on the obedience of everybody else, right? When that obedience is withdrawn they lose their power.

00:40:00 Corporations lose their power when their workers no longer obey, when their workers go out on strike. Corporations lose their power when consumers don’t obey, and consumers boycott their books, their goods just as the farmworkers did back in the 1960s. And governments lose their power to make war when the population no longer goes along with the war, and when the military begin to resist the war, which is what happened during the Vietnam War. So, power demands obedience. When people begin to disobey then that apparently absolute power begins to crumble, and people come into their own.

People Can Change

00:40:42 So I think these are important things for all of us to keep in mind and for young people to remember. And one more thing, maybe. Just one thing. People change. It’s important to know this because, you think, well, can people really change their mindset?

00:41:01 Yes. People can change their mindset. And by the way, the election of Obama shows that there were white people who changed their mindset, have changed over the course of these last decades. Obama couldn’t have been elected thirty years ago, you know that. There were people who changed their minds. You didn’t have to change the minds of Black people about Obama. They had to change the minds of white people and enough of them changed their minds. And, living in the south, being involved in the movements for those seven years that I was there, saw people change.

00:41:34 Saw white people change. People can change. Well, we’ve seen the country first supporting the war and supporting Bush, and then some years later the people had changed. That gives us hope.

Thank you.

Questions and Answers

00:42:22 Host: Thank you for what you’ve done, thank you for who you are, and thank you for speaking with us today. We’re going to take questions, and then we’ll be heading down to bookstore, and we ask that if you want to go on down there, we’ll try to get down there as fast as we can. If there are any questions, there is a microphone back over there. And please, if you would just speak up and identify yourself because I can’t see through the lights.

00:42:50 Female Voice 1: Alright, is it on? Can you hear me? I’m Dr. Cynthia Dubois from the University of Texas and I’d like to thank Dr. Zinn for his presence and for giving me the courage for the last thirty years to teach what I knew needed to be taught, and to take the rap that went with it sometimes. My question is now that we – it looks like we have the sea change in the way things are going, do you think that we can motivate and continue the young peoples’ enthusiasm for the change that Obama keeps recommending and advocating for?

00:43:39 Are we going to get those young people now they voted, out and working and being the community organizers that are going to create the change?

00:43:50 Howard Zinn: Well, that’s, of course that question remains to be answered, but there’s a good basis for answering it positively. Because this election, unlike previous elections, I didn’t see such a turn out for Kerry and – and Gore, or Clinton, or – no. But we saw such a turnout of enthusiastic young people, Black and white, in this situation. That we have the reservoir of energy and enthusiasm there that can – yes, bring about the change that was promised in that mantra “change” that we heard in the course of the campaign. But, you know, it’s up to us to encourage that.

00:44:34 Male Voice 1: Good morning Dr. Zinn. My name’s Nathan and I’m a student, and I was just curious to hear your opinions about the electoral college.

Howard Zinn: Do I have an opinion about the electoral college? Of course. It’s ridiculous. Yeah. I mean, the political system is undemocratic enough without the electoral college.

00:45:31 I mean, undemocratic in the sense that, you know, we only have two parties and third parties, you know, cannot get on the ballot, they cannot get on the debating platform. And there are all sorts of obstacles put in the way of people voting and registering. You know, there are a lot of things wrong with the electoral system. But certainly, the electoral college is a very important part of what’s wrong and should be immediately flunked.

00:46:09 Male Voice 2: Hi, Professor Zinn. Thank you so much to be here. Wonderful presentation. I’d like to ask about your thoughts on the economic crisis. You were critical of the bailout.

Howard Zinn: Yes.

Male Voice 2: And, I’m wondering what you would do. If you think that this economic crisis is as serious as what was faced in 1929; if it has a potential to bring a depression and what you would do.

00:46:36 Howard Zinn: I’m glad you asked me that question because it implies that I know. And in fact, you are right, I do know. Well, I think I know. I believe we ought to react to this crisis, and as you say it’s a crisis that – that has some of the characteristics of 1929, and we might be going into a depression like the 1930s. One thing I’m sure, and that is giving seven hundred billion dollars to the same financial institutions that have ruined us is not going to help the situation.

00:47:20 That’s why I was disappointed to see Obama and McCain joining in supporting, you know, this bailout. To me that represents what we used to called the trickle-down theory. You pour the money into the top and – but the people at the bottom are the ones who are suffering. They’re the ones – and it’s their lack of purchasing power which is causing the problem in the first place because they’ve been so beset over the years with inequality, and they’ve been losing and losing, while the people at the top have been gaining and gaining, and this gap has grown and grown.

00:45:56 And that huge gap, which in the 1920s also grew and grew with Andrew Mellon, secretary of the treasury, you can imagine how egalitarian he was.

And so we have this gap, and the people below — the mortgage – you know, people who are trying to pay their mortgages, and so on, and people who are losing their jobs, they’re the ones who need the help. And – and the idea that money will somehow trickle down from the financial institutions to these people and solve the problem – no. The thing to do is take that seven hundred billion dollars and more, in fact more is already, you know, in the works to give more to the top – and give that money directly, use that money directly to help people.

00:48:41 Forget about the banks. Use that money to help the people who have to pay their mortgages. Use that money to give people jobs, for the government to give people jobs. For the government to do what the New Deal did, and here we can learn from the history of the New Deal and FDR. What did they do? They faced an economic crisis, they faced joblessness on a large scale, and the government did, you know, what no democratic candidate has had the courage to say because they’re afraid of being accused of being for big government, which is very funny when you think of it.

00:49:20 What’s bigger than the government bailing out these banks. That’s big government. So, they’re afraid of big government so – but no. The government needs to give people jobs. The New Deal gave jobs to millions of people, millions of people. They gave jobs to hundreds and hundreds of thousands of young people. Instead of giving them guns to go overseas and fight, they gave them picks and shovels and they build all sorts of things. These young people in the CCC, you know, they built playgrounds and they repaired bridges and they cleaned up waters, and they did all sorts of, you know, they planted trees, and did all sorts of wonderful – so, yes.

00:50:01 We need to use money, the money that would be going in the bailout, the money that can be accumulated by larger taxes on the super-rich, the money that can be accumulated by no longer being a military superpower that has to spend six hundred billion dollars a year on the military. Huge sums of money can be saved and that money can create free health care for everybody, can create jobs program, can double teachers’ salaries, can give free education, higher education . . .

00:50:37 In other words you have to take – I’m surprised that Obama didn’t look back to the New Deal and FDR because they still resonate with people, FDR and the New Deal. Look back to them as a model and even go beyond them. We need a New Deal, and even more than a New Deal, because we really have to get at the foundations of the economic problem.

00:50:59 And the foundations of the economic problem are the system, the profit system, the – yes, the capitalist system, the corporate – the system of corporate power. We need a more democratic economic system. Not a centralized bureaucracy, not, you know, because whenever you – whenever you criticize capitalism, they say, “Oh, you want the soviet system.” No. No, there are things in between. There are – all – various alternatives, which would take care of people better than we take care of them now.

Male Voice 2: Thank you very much.

00:51:36 Female Voice 2: Hi, I’m Liz Morrison, I’m the coordinator of social studies for the Parkway School District, K – 12, located in St. Louis, Missouri, and I’m the mother of a seven year old, an eleven year old, a sixteen year old, and a nineteen year old. My thinking here is this. Your audience today is made up of K through 12 teachers, as well as college professors and other people from around the country who are connected to social studies education.

00:52:01 And I think as social studies educators we face a very unique challenge of trying to foster pride in our country while tempering that with the realism of what that means to be an American. And I would like you to kind of address that as well as the other question I had about — you mentioned the heroes, and I do not disagree with you. I think we have many, many heroes in America, but some of the other heroes I don’t think should be neglected and also, I think by leaving out some of our military heroes, that’s a bad thing.

00:52:30 They just celebrated Veterans’ Day recognizing their service. One of my students, [Josh Eckoff], was injured in Iraq seriously and – and Josh believes in his country and he believes – and I know what you were saying about government and country. How do we address that as teachers at different levels without thinking – my son is six, and he has a different view of what America is than a high school student or a college student about what that means. So, thanks and that made me very nervous.

00:52:58 Howard Zinn: Well, that’s very important questions. You know, the – yeah, so guys go to Iraq, women go to Iraq, come back, they believe in what they did and they believe that they were fighting for their country even though, as I believe and as maybe years later they might decide also, they weren’t fighting for their country, they were fighting for their government and whoever would profit in the war. But still, you have to take account of how people feel.

00:53:28 But, you have to recognize how they feel and – and of course, you have to care about them. You have to care about the veterans who come back. You have to care about the GIs who are there. Care about them not in order to keep them there but care about them by bringing them home, and getting them out of that thing that may kill them or dismember them. So it is a very delicate matter of dealing with this. As for recognizing military heroes, now, you talked about Veterans’ Day, and I always think about it, right, because I’m a veteran.

00:54:01 I’m a veteran of World War II. I was a bombardier in the air force in World War II, and yes, Veterans’ Day. But I don’t want Veterans’ Day to celebrate war. I want Veterans’ Day to celebrate a time when there will be no more veterans. Yes, recognize veterans, recognize – of course. Veterans – you know, people who suffer, who saw their friends die and who themselves may have come back injured.

00:54:30 No, they deserve to be recognized, not because they necessarily engaged in a good thing, because many of these wars are not good things. But, you know, people, young people, can engage in something which is not good, like the Vietnam War, or like the war in Iraq, but they thought they were – they thought they – and so they – their feelings have to be recognized without going overboard, and without being dishonest about the kind of wars that they have been in and that they have suffered in.

00:55:05 So, you know, as I say it’s a complicated and delicate matter. And as for, you know, celebrating military heroes, I don’t know which military heroes you’re thinking about. But I don’t think just the fact that somebody has served in a war makes that person a military hero.

Female Voice 2: I was thinking like George Washington.

Howard Zinn: Oh, like George –

Female Voice 2: He’s a traditional hero that we talk about in school, and for first graders.

00:55:31 Howard Zinn: George Washington. Well, that brings up the Revolutionary War, and I think the Revolutionary War needs to be re-examined. I don’t want to take down George Washington, but I think people ought to have a more realistic picture of the distinction between the elite – the Washingtons and the Adams and the Madisons and the Jeffersons – that greater distinction between them and the rest of the population.

00:56:03 I mean, George Washington, yes, he was a very good general, he was a very good military strategist, and so on and so forth. He was also a slave holder and he also was, reluctant to use Black people in the revolutionary army, while the British, who were not reluctant, and they gave freedom to slaves who fought in revolutionary army. And you know, I would recognize Washington for his military savvy, and so on, and courage and so on.

00:56:36 I’d also recognize the soldiers in his army, the rank and file, the people who mutinied against him. The thousands of soldiers who mutinied against the officers, against Washington, and why? Because the officers were being treated like nobility and the ordinary soldiers were really being treated like dirt, and they were not getting food and not getting their pay, and not getting clothes and so on.

00:57:06 In other words, the Revolutionary War is more complicated than the simply heroic story that’s told about, well, we fought a revolution against England, and everything about our revolution was heroic, and everybody who participated – no. It’s more complicated than that. Yes, we won independence from England. But it was in many ways a revolution that was riddled with elements of class difference and, you know, Black slaves did not benefit from the revolution.

00:57:43 And I don’t remember learning, and I don’t know if it’s still taught this way, when they talk about the revolution do they talk about the fact that the Native Americans were not happy about the American Revolution? They did not benefit from it. They lost from it, because the British had set a line beyond which they settlers could move into Indian Territory, when the American colonists won over England, established independence, they obliterated that line.

00:58:09 The Proclamation of 1763. And then, it’s colonists could move into Indian Territory. From the point of view of the Indians, the revolution was not a happy thing. So, not from the point of view of slaves, not from the point of view of Indians, not from the point of view of many of the sort of farmers and working class people who fought in the war.

00:58:32 The revolution was not simply the kind of pure and totally good thing that our culture, our history, our movies, our textbooks portray it. And for students to learn that something is complicated rather than morally simple, I think it’s a good idea to get them accustomed to the idea that things are complicated.

Female Voice 2: But my question is for a six year old. That was what —

Howard Zinn: Yes.

Female Voice 2: I mean, for a six year old. How many people have six year olds? Yeah, sorry, OK.

00:59:05 Howard Zinn: Well, should you be honest with a six year old?

Female Voice 2: No, not — that’s not what I’m asking.

Howard Zinn: I don’t know. I’d like somebody else who has a six year old, there must be somebody here who has a six year old. I mean, this question comes up very often. So what you can tell a young person? What can you tell a six year old – can you tell, you know.

00:59:31 I believe you should be honest with kids at any age. You may tell them the story differently and more simply, but I don’t think you should tell them, untruths, whether it’s about Columbus or about George Washington.

00:59:55 Female Voice 3: Alright. Hi, Dr. Zinn, thanks for coming today, and there are many things I’d love to ask, but I’ll limit it to one: Campaign finance. We all agree it’s gotten out of hand, but what can we do about it?

Howard Zinn: I think we need to spend more money on elections. No, I’m sorry. No, you’re absolutely right. Campaign finance has gotten totally out of hand, elections should not be based on who raises the most money.

01:00:28 There should be public money available for candidates, not just of the major parties but of other parties, and shouldn’t be a situation of whoever has the most money has the most television time and therefore the greatest chance of winning. So, yeah. Campaign finance, very serious matter.

Thank you.

Host: Thank you very much. We will see you in Atlanta. We’ll be down at the bookstore to sign books.

The Zinn Education Project distributed 800 copies of A People’s History for the Classroom for free to the participants. The keynote presentation was supported in part by HarperCollins.

55 White Men, and no common interest of the people? A little reconstruction of both history and reality here!

Let’s make this easy, 55 white men did not single-handedly, without the support of the people rebel and defeat the British. Long before they came together, former Irish Slaves were coming down from the Appalachians and burning the homes of Loyalists Plantation owners. Many Colonists were protesting the Sugar Act, Stamp Act, etc. Mostly merchants. Motivation included the Irish hatred of the British for Cromwell’s Slaughter of their homeland, exile to plantations, men taken from their families and sol to France and Spain as soldiers. (Canon Fodder)