Which country is the No. 1 supplier of oil to the United States? Saudi Arabia? No. Iraq? No. Russia? No.

My geography students were surprised to learn it’s my country — Canada. Most of that oil comes from the tar sands located in northern Alberta, in an area roughly the size of Florida. The Alberta tar sands are home to the world’s second largest deposit of oil, after Saudi Arabia. They are also the source of great controversy, seen by some as “Canada’s greatest treasure” and others as “Canada’s greatest shame.”

As a Canadian teaching at an international school in New York City, I had long been planning to teach about the tar sands. Although many people are aware of the devastating effects of BP’s oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico or Shell’s human rights abuses in Nigeria, few know about the enormous environmental and social injustice caused by oil extraction just to the north. The perfect opportunity to teach about this issue arose this past fall when the media focused attention on the proposed TransCanada Keystone XL pipeline. If approved, this pipeline would have brought as much as 700,000 barrels a day of crude oil from Alberta’s tar sands to refineries in Texas.

Who would benefit most from the pipeline? Who would suffer? What would be the pipeline’s long-term effects on the environment, economy, and on local communities? Should we support or resist increasing the capacity of the tar sands? These were the questions that I wanted my geography students (most of whom come from relatively privileged backgrounds) to consider.

To confront these questions, I wrote a role play where students take on the characters of six key stakeholders invited to an imaginary public hearing, chaired by then-U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton (played by myself), to discuss whether or not the State Department and the president should approve the Keystone XL Pipeline.

Key stakeholder roles included with this lesson are:

- The Tar Sands and the Keystone XL Pipeline

- TransCanada

- American Petroleum Institute

- The Republican Party

- Environmental Activists

- Indigenous Environmental Network

- Bold Nebraska

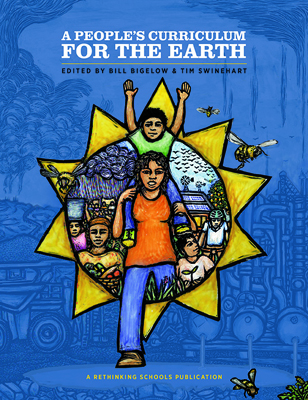

This teaching activity was originally published by Rethinking Schools and is included in their book A People’s Curriculum for the Earth.

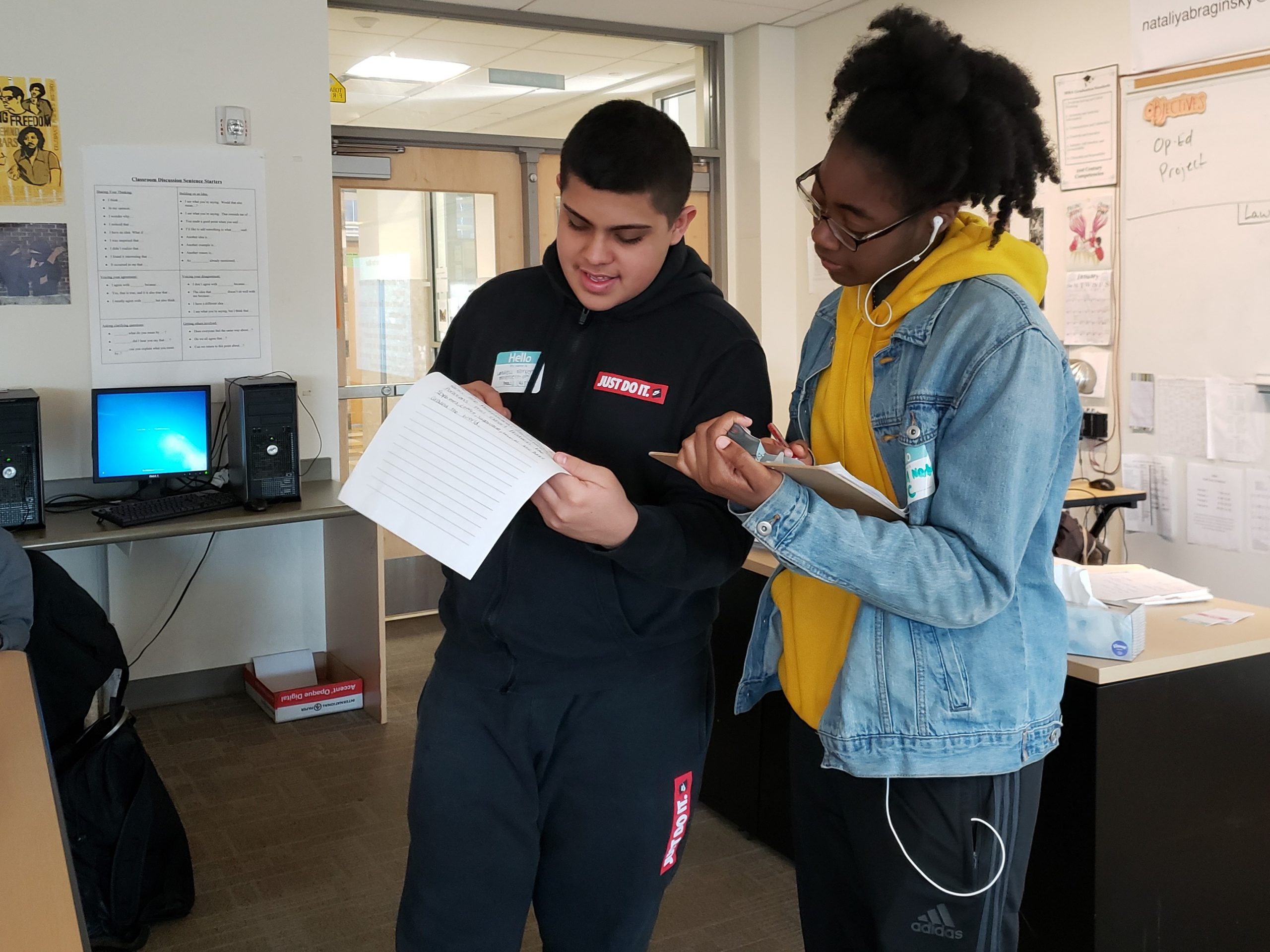

The struggle to engage my students has been real. I teach Geography and Economics. My 7th hour, the last hour of the day, is the class I struggle with. This class had the largest amount of IEPs and behavior issues. At least 4 of my students are at a 2nd grade reading level. Many of the students have constant beef with each other. It is hard to teach. After getting the students in their seats and giving them a short preface on the issue at hand, I put them in groups and handed out the assignment.

I walked around, my fingers crossed, hoping for the best. I almost cried in joy with what happened next. I am going to share two examples of students that surprised me. The first one I will name Mohammad. I have always known Mohammad was smart. However, he constantly loves to act out in class. This time, I told him I was placing him as the leader in the group. When I came around to his group, I was amazed. He was leading the group in a discussion about what points they should bring up in their debate the next day. He included his fellow peers and took down notes. I was amazed. He was excited about representing the Indigenous group. I was ecstatic at hearing their conversations! I thought I was set for the day.

Then I turned to another one of my strong characters in my class. Just like Mohammad, Kyle loves to shout in class and constantly act up because he does not want people to know that he can’t read like everyone else. However, in this moment, he was confident and he was ready to learn. When I turned to listen to Kyle’s group, I saw him writing down everyone’s ideas. Even though the reading was above his level, his peers were helping him decipher the text by summarizing important paragraphs for him. I asked him if he felt as if his group was ready. He told me, “We are going to win! Can we do this again? I really like my group.” I decided to take a moment and listen to the classroom. A moment I don’t always have. I heard student’s explain, “This pipeline is going down!” “I wonder what else we are going to learn about Canada.” “How is this going to impact Kansas City?”

Students were in their seats, lively chatting back and forth. In that moment, I knew this was where I needed to be. It is one more step closer to creating community and solidarity in my classroom. Lastly, I don’t think that I will ever forget the smiles on my 7th hour’s faces when I told them that I was proud of them. That they were becoming the game changers that I knew they could be. —Christina Hendrix, middle school social studies teacher, Kansas City, MO

So relevant and useful right now. Thanks for giving me the opportunity to share this with my children. The role plays are such effective teaching tools.

Thank you for sharing! I have been wanting to present a lesson on the Tar Sands but have not had time to do adequate research. Your lesson looks like a great starting point for my Environmental Science classroom.