The Teacher Activists Groups network is sponsoring a No History Is Illegal campaign in support of Tucson’s Mexican American Studies (MAS) program. The program was declared illegal by the state attorney general Tom Horne. Classes were terminated and books were banned by Feb. 1. As part of the No History Is Illegal campaign, teachers across the United States are encouraged to teach lessons and use books from the banned Mexican American Studies program.

The Teacher Activists Groups network is sponsoring a No History Is Illegal campaign in support of Tucson’s Mexican American Studies (MAS) program. The program was declared illegal by the state attorney general Tom Horne. Classes were terminated and books were banned by Feb. 1. As part of the No History Is Illegal campaign, teachers across the United States are encouraged to teach lessons and use books from the banned Mexican American Studies program.

Teachers are also invited to sign this pledge:

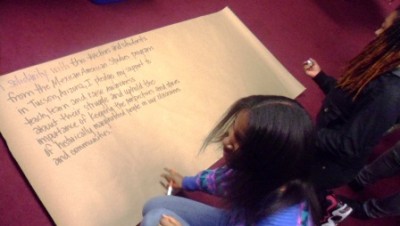

“In solidarity with the students and teachers from the Mexican American Studies program in Tucson, AZ, I pledge my support to teach and raise awareness about their struggle and uphold the importance of keeping the perspectives and stories of historically marginalized people alive in our classrooms and communities.”

Teacher Takes the Pledge

Teacher Takes the Pledge

English teacher Monét Cooper wrote to us about the approach she took to raise awareness about the struggle in Tucson with her 10th graders at Capital City Public Charter School in Washington, D.C.

She explained that: “After watching excerpts from the documentary Precious Knowledge about the Mexican American Studies program benefits and attacks, I knew this was an issue my students needed to discuss and take action on in the classroom. I quickly wrote a lesson plan based on a poem by Martín Espada and our current theme of bullying.”

The Lesson

Cooper had students read and discuss a poem by nationally respected poet and essayist Martín Espada. Espada is one of Cooper’s favorite poets and his work was used by the Mexican American Studies program. He recently wrote an essay for The Progressive about being on the “banned list,” calling it an honor to be “keeping company with ancestors. I am keeping company with some of the finest Latino/a writers alive today.”

In each of her four classes, Cooper repeated the same lesson, engaging students in a poetry study that was interrupted by a prearranged intruder.

She began the lesson by having students read and discuss the poem in small groups, using guided questions she had prepared in advance. Suddenly, another teacher or administrator interrupted the class.

She began the lesson by having students read and discuss the poem in small groups, using guided questions she had prepared in advance. Suddenly, another teacher or administrator interrupted the class.

She or he told Cooper: “Is the poem your students are reading written by someone who’s African, African American, Native American, Asian, or Latina/o? If so, we can’t read that here.” The person went on to say: “Ms. Cooper, didn’t you check your email? If we don’t do this, the auditors could stop by at any moment and take our accreditation and we’ll have to close the school. So, quickly, hand them over.”

She or he then turned to the class and said: “Students, you’ll have to give me those papers. Yes, all of them.” (Note that the actual language of the bill outlaws the teaching of the Mexican American Studies curriculum and any program with classes that might promote resentment based on race or class, or might promote ethnic solidarity. Here is the actual bill, HB 2281.)

“It was interesting to observe what happened in different classes,” Cooper commented. “All of them were surprised. All of them asked me if they were serious. All of them had someone who immediately handed their papers over. All of them wanted to offer their support to the students in Tucson once they learned the true story.”

Student Reactions

Cooper shared with us some of the specific responses from a few of her six class periods.

| Period 1: Students kept asking me if this was “for real.” One person started laughing. Another said, “They can’t do this!” Later, during class discussion, Maurelys told the class that Katie whispered, “I still have a few sheets in here,” and she tapped her closed book. The students in that class discussed their initial confusion about what was happening during the disruption and that they couldn’t imagine that happening in Washington, D.C. When I said that it was happening in Tucson, Ariz.,—refreshing their memory about what we briefly discussed yesterday—and showed them the Precious Knowledge documentary trailer and the class’s recitation of the banned poem “In Lak’ech” they were incensed. “How can they do that?” After that discussion, we moved on to issues of power—who had the power to ban Ethnic Studies programs in Arizona, who has the power to change that—and we wrote poems about bullying and power, mirroring the discussions we had around Espada’s poem. | |

| Period 3: The students were much like first period, except some of them were verbally resistant, refusing to hand over their papers when their world history teacher Mr. Malone demanded it. One student even said, “Let’s get him, Ms. Cooper!” Others willingly handed over their papers, but looked at me with questions in their eyes. | |

| Period 5: Same similarities during discussion, except during the initial disruption, one student pretty much led the class in handing the poems over to Ms. Aberger. No one knew who she was, which made them more inclined to give their things to her. Cleo screeched, “Come on, give her your stuff, then we won’t have anything to learn!” Her words hit home after we watched the video. One student asked, what are they learning? I said, “I don’t know,” adding that some of them are probably thinking the same thing, but also saying, “There’s always something to learn, if you’re willing.” We discussed what else the students were learning: ultimately, how to take action against authority; to learn even when banned from doing so. | |

| Period 6: Much of the same scenario, but even after a discussion and showing the video, many students still thought that the book ban was happening and wanted to do something about it at our school. As Ms. Shelden was coming around and taking up papers, Josue asked me, “Does she want the Richard Santiago essay, too?” I put my index finger to my lips as if to say, “Keep that quiet.” He either put it away or had to give it to her, I can’t remember. Some students who saw the exchange put certain items away. |

Taking Action

In each class, Cooper explained that this had been a simulation with respect to their school, but that in Arizona the ethnic studies curriculum has been outlawed and their books have been taken away. She then showed the trailer for Precious Knowledge.

All classes had a discussion about what they could do to support their peers in Arizona who must adhere to the ban. Several ideas were given:

All classes had a discussion about what they could do to support their peers in Arizona who must adhere to the ban. Several ideas were given:

- go to Tucson, Ariz.;

- write a letter to (the school board, the governor, the students/teachers); and

- watch the full documentary.

After discussing the power of information, they settled on writing a letter to the editor of the Washington Post which has yet to cover the story. The students said they would ask why it has not been covered given its relevance in the context of the resurgence in anti-immigration legislation and a national debate on education and student achievement.

Cooper asked the students to write a first draft of their letter to the editor of the Washington Post for homework.

Finally, before leaving class, students were given the opportunity to sign a modified version of the teacher pledge from the No History Is Illegal website, copied on a huge sheet of paper.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn