The following description of the film was written by film producer Judy Richardson for H-Net.

The following description of the film was written by film producer Judy Richardson for H-Net.

Slave Catchers, Slave Resisters is a two-hour History Channel documentary that depicts the system of slave policing — enforced by militia, armed community slave patrols, paid slave catchers, and federal law.

The stories are set in both the South and the North, from the mid-1700’s colonial era through the end of the Civil War and its aftermath, and told through archival material, scholar interviews and recreations.

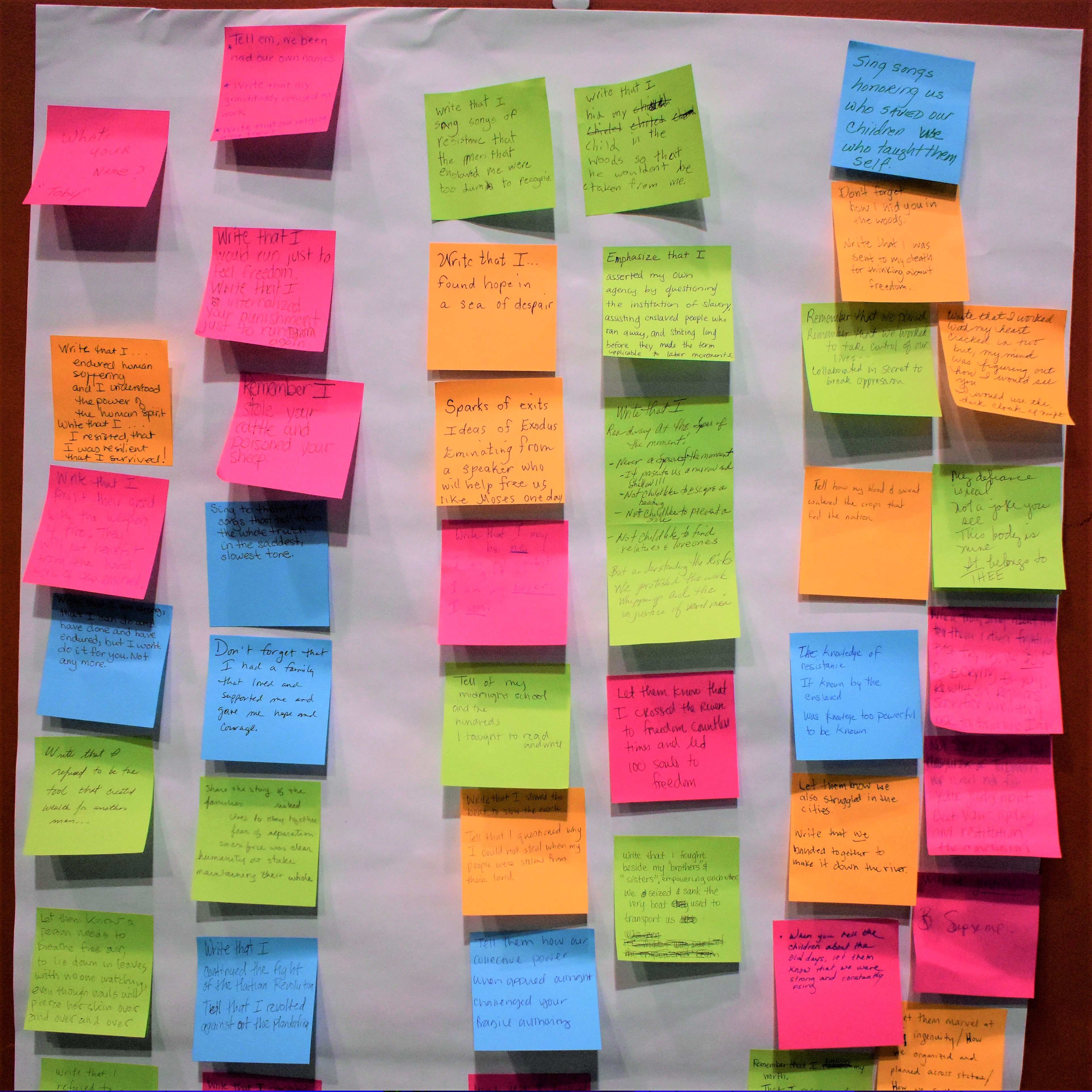

While the stories show the brutality of the slave system, they also reveal another, often-overlooked side of the history — the strength and ingenuity of the enslaved. As historian Peter Wood observes, “Would they [the enslaved] go willingly into a situation of perpetual racial servitude? No way!”

In the South, we portray slave hunters and their bloodhounds, who sometimes lost against the intelligence and fight-to-the-death courage of the enslaved. And in the North, we show slave catchers who were sometimes blocked by an organized — and armed — black community. Historian James O. Horton comments: “Boston is not a safe place for slave catchers to operate. . . Blacks — and sometimes whites — formed as groups to protect fugitives.”

Even in the South, plantations were like pressure cookers, as our film illustrates. Sometimes they exploded into full-scale rebellions — like the 1739 Stono Rebellion in South Carolina or the 1831 rebellion led by Nat Turner in Virginia. But, more often, they were plagued by the low-level simmering of individual acts of resistance. One Philadelphia company even refused to issue fire insurance policies in slave states because of the high incidence of arson.

However, as we make clear, the main problem for slave owners was not rebellion, but runaways. Historian Loren Schweninger notes, “A minimum number of slaves per year that ran away was 50,000 and probably many more. . . It was almost routine.” Most ran simply to be reunited with family members who’d been sold away.

During the Revolutionary War, Thomas Jefferson noted that thousands of slaves fled Virginia plantations alone, including some from Jefferson’s own plantation. One of Patrick Henry’s slaves took to heart Henry’s cry of “Give me liberty, or give me death” — and fled. Even the power granted the slaveholding states in the new Constitution could not stop slave escapes. Historian Sylvia Frey states, “The enslaved population had waged a desperate. . . but unsuccessful struggle for freedom, [but] the impetus that the Revolution provided persisted.”

To stanch the flow of escaping slaves, plantation owners used a variety of methods over time: an elaborate system of slave patrols with rigid rules, Negro Acts and other legislation, “Negro dogs” especially bred to track runaways (including some bred by a future U.S. president), and slave catchers hired in the South and the North.

Our documentary tells true stories of slave catchers and escaping slaves that have never before been portrayed on film. And threaded throughout these unusual and little-known stories is information about the tools slave hunters used to bring back runaway slaves, the strategies used by the enslaved to thwart their pursuers. . . and the lengths to which both would go to achieve their goal.

We close on the aftermath of the Civil War, as the newly freed people work to build their communities, with farms, schools and churches. But the system of slave police has not disappeared — it is soon reborn in an even more violent form: the Ku Klux Klan. As historian Sally Hadden, author of the definitive book on slave patrols, explains, “The Klan is an extension of slave patrols in most direct, obvious ways. . . they’ve changed the names from patrols to Klan, they’ve put on sheets, but the activities and the purpose remain pretty much the same.”

Yet, while these stories acknowledge the brutality of slavery, they reveal something much deeper: that within the darkness, there was also light. For, even during the darkest days of slavery — even when freedom seemed no more than an illusive dream — the enslaved and their supporters continued to struggle against overwhelming odds . . . and sometimes won.

Produced by Judy Richardson of Northern Light Productions. Judy Richardson is also the filmmaker for Scarred Justice: The Orangeburg Massacre 1968, series associate producer of Eyes on the Prize, and co-editor of Hands on the Freedom Plow: Personal Accounts by Women in SNCC.

Watch Online

Related Resource

- Nat Turner: A Troublesome Property. A California Newsreel film.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn