When I included the poem “The Prison Cell” in my first anthology of poems for young readers, This Same Sky (Four Winds Press, Macmillan, 1992), I had not yet met the poet Mahmoud Darwish, but had been reading his poems in English translation since I was a teenager.

It would surprise me, in years following the appearance of my first anthology, how many U.S. teachers (in high schools particularly, but also middle schools) would ask me to read this particular poem out loud during my presentations.

Somehow, Darwish’s simple, strong poem “The Prison Cell” had the power to encourage people to sit up straighter, take note — and discuss or contemplate issues of injustice, as they recognized them. Latino students in Santa Fe, for instance, seemed profoundly moved by the poem and the possibilities of reclamation and enduring power it suggests.

Darwish, beloved as the beacon-voice of Palestinians scattered around the globe, had an uncanny ability to create unforgettable, richly descriptive poems, songs of homesick longing, which resonate with displaced people everywhere.

Darwish, beloved as the beacon-voice of Palestinians scattered around the globe, had an uncanny ability to create unforgettable, richly descriptive poems, songs of homesick longing, which resonate with displaced people everywhere.

It would have stunned me to imagine that I would stand next to him on stage, along with the poet Carolyn Forché, reading his poems in English after he read them in Arabic at an event some years ago at Swarthmore College, when he received the Cultural Freedom Award given by the Lannan Foundation. He spoke English well enough to have read his own translations, but did not want to.

It would have stunned me even more that he would die prematurely in August of 2008, at the age of 67, after heart surgery, in a Houston hospital in my own adopted state. I had awakened the day he was put on life support, feeling intensely that someone very precious was getting ready to pass out of the world. I nervously mentioned this to my husband a full day before we learned it was true. Perhaps someone very precious is getting ready to pass out of this world every minute.

Now we are left to encourage one another to read Darwish, and to believe in the quest for justice, which he, and so many other homesick Palestinians, never abandoned.

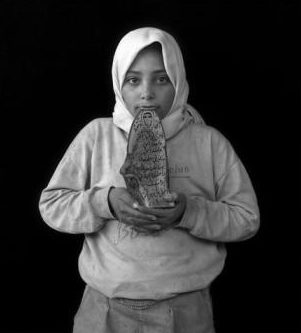

A little Darwish tale worth telling: My husband, photographer Michael Nye, once photographed in a West Bank Palestinian refugee camp for days, and was followed around by a little girl who wanted him to photograph her. Finally, he did — and she held up a stone with a poem etched into it. (This picture appears on the cover of my collection of poems, 19 Varieties of Gazelle — Poems of the Middle East.)

A little Darwish tale worth telling: My husband, photographer Michael Nye, once photographed in a West Bank Palestinian refugee camp for days, and was followed around by a little girl who wanted him to photograph her. Finally, he did — and she held up a stone with a poem etched into it. (This picture appears on the cover of my collection of poems, 19 Varieties of Gazelle — Poems of the Middle East.)

Through a translator, Michael understood that the poem was “her poem” — that’s what she called it. We urged my dad to translate the verse, which sounded vaguely familiar, but without checking roundly enough, we quoted the translation on the book flap and said she had written the verse. Quickly, angry scholars wrote to me pointing out that the verse was from a famous Darwish poem. I felt terrible.

I was meeting him for the first and last time the next week. Handing over the copy of the book sheepishly, I said: “Please forgive our mistake. If this book ever gets reprinted, I promise we will give the proper credit for the verse.” He stared closely at the picture. Tears ran down his cheeks. “Don’t correct it,” he said. “It is the goal of my life to write poems that are claimed by children.”

‘The Prison Cell’

It is possible . . .

It is possible at least sometimes . . .

It is possible especially now

To ride a horse

Inside a prison cell

And run away . . .

It is possible for prison walls

To disappear,

For the cell to become a distant land

Without frontiers:

What did you do with the walls?

I gave them back to the rocks.

And what did you do with the ceiling?

I turned it into a saddle.

And your chain?

I turned it into a pencil.

The prison guard got angry.

He put an end to the dialogue.

He said he didn’t care for poetry,

And bolted the door of my cell.

He came back to see me

In the morning.

He shouted at me:

Where did all this water come from?

I brought it from the Nile.

And the trees?

From the orchards of Damascus.

And the music?

From my heartbeat.

The prison guard got mad.

He put an end to my dialogue.

He said he didn’t like my poetry,

And bolted the door of my cell.

But he returned in the evening:

Where did this moon come from?

From the nights of Baghdad.

And the wine?

From the vineyards of Algiers.

And this freedom?

From the chain you tied me with last night.

The prison guard grew so sad . . .

He begged me to give him back

His freedom.

—Mahmoud Darwish (1941–2008)

Translated by Ben Bennani

‘The Prison Cell’

Teaching Idea

By Linda Christensen

As Mahmoud Darwish portrays in his poem, as long as our minds are free, human-made prisons cannot contain our imaginations. After reading the poem with students, ask: “What imprisons you? Think metaphorically. For example, growing up, poverty imprisoned me. Sometimes, school imprisoned me. Other people’s ideas about women’s role in society imprisoned me. Create a list of the ways you have been imprisoned.”

Share and discuss students’ lists. “Now create a second list: things you love. Darwish brings his land to the prison: the Nile River, trees, music. What do you bring to your prison that helps you escape, that feeds your soul? Notice how specific Darwish is. He names the river, the orchards. He tells us where the wine is from. Get specific. Does your joy come from singing in the Maranatha Church on Sundays? From smelling your grandmother’s sweet potato pie?” After students have listed, ask them to share and add to their lists.

Darwish begins with the line: “It is possible”:

It is possible for [what to disappear? school

walls? prejudices against women?]

For the cell to become [what is your dream

place: a library? your neighborhood?]

For example:

It is possible for your contempt for my

language to disappear.

For the cell to become a room

Where my ancestors’ voices can sing again.

Ask students to write a first stanza using Darwish’s frame as a model. Ask a few students to share to give others ideas.

Then Darwish moves into conversation with his jailer. Help students notice the question-answer between the poet and the jailer.

Encourage students to begin a dialogue between the oppressor and the liberated as Darwish does.

For example:

What did you do with the rules we created

for you?

I gave them back to your books that made

me small.

Where did voices come from?

I freed them from the shame that made their

voices fade.

Darwish’s poem should provide a model, not a prison cell, as students write their own. The intent is to get at the richness that emerges when students begin to name the invisible forces that imprison them.

About the Authors

Naomi Shihab Nye grew up in Ramallah (then in Jordan), the Old City of Jerusalem, and San Antonio, Texas. She is the author of numerous books of poetry. In 1988 she received the Academy of American Poets’ Lavan Award, selected by W. S. Merwin. She lives in San Antonio.

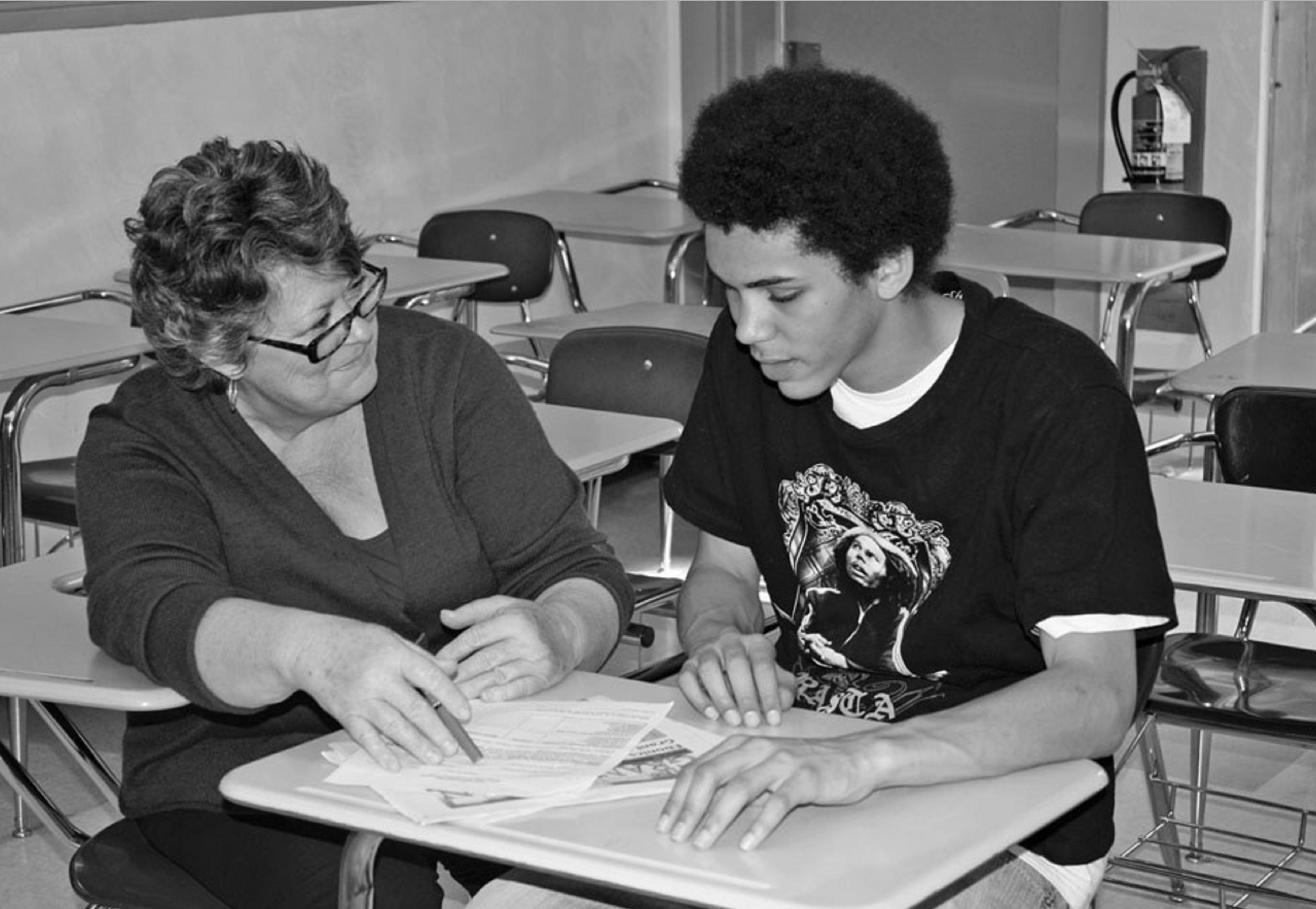

Linda Christensen is Director of the Oregon Writing Project at Lewis & Clark College in Portland, Oregon. During her thirty-year career in Portland Public Schools, she taught language arts at Jefferson and Grant High Schools and worked as Portland’s Language Arts Coordinator. She is on the editorial board of Rethinking Schools and author of Reading Writing and Rising Up: Teaching About Social Justice and the Power of the Written Word and Teaching for Joy and Justice: Re-imagining the Language Arts Classroom.

This lesson was published by Rethinking Schools in an edition of Rethinking Schools magazine, “Marketing American Girlhood,” (Winter 2008/9; Vol. 23, #2). See Table of Contents. For more articles and lessons like “Remembering Mahmoud Darwish,” see the Rethinking Schools books by Linda Christensen: Reading Writing and Rising Up: Teaching About Social Justice and the Power of the Written Word and Teaching for Joy and Justice: Re-imagining the Language Arts Classroom.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn