As part of our Teach the Black Freedom Struggle series, historians Robyn C. Spencer and Mary Phillips joined educator Jesse Hagopian to discuss what they have learned from and about the women of the Black Panther Party.

Spencer and Phillips challenged prevailing stereotypes about the roles and significance of women in the Black Panther Party. We share the text of their conversation for discussion in high school classrooms and professional development workshops.

Mary Phillips: I want to begin our conversation by talking about when women joined the Black Panther Party and why they joined. There were many Black Panther groups inspired by the Lowndes County Freedom Organization. Many people are probably familiar with that organization and their symbol of the Black Panther. In 1966, in Oakland, California, Huey P. Newton and Bobby Seale co-founded the Black Panther Party. Women joined a year later in the spring of 1967.

Mary Phillips: I want to begin our conversation by talking about when women joined the Black Panther Party and why they joined. There were many Black Panther groups inspired by the Lowndes County Freedom Organization. Many people are probably familiar with that organization and their symbol of the Black Panther. In 1966, in Oakland, California, Huey P. Newton and Bobby Seale co-founded the Black Panther Party. Women joined a year later in the spring of 1967.

The first woman to join the Black Panther Party was actually a young teenage girl named Joan Tarika Lewis [see video below]. She was a student activist in her high school, and she was very adamant in advocating for Black History Club at her high school. When she came to the Black Panther Party headquarters she actually demanded to join the organization and pointed out the lack of women that were part of the organization at that time. So her presence opened the door for others to join. Just like the men, the women wanted to serve their communities in very practical ways, to address issues like police brutality. They wanted to respond to conditions of civil rights. They were also part of local civil rights struggles. Some were attracted to the political ideology and for others joining the organization was a natural outgrowth of long standing activism in their families.

I became very involved in that level of politics because it was an extension of what I knew, an extension of what they call the Deacons for Defense down south. My grandfather was the first person to buy land on what was considered the white part of town. I’d go visit him in the summers and I remember that the Ku Klux Klan burned a cross on his yard because they opposed him living on that side of town. I remember asking him, “Papa, why you always got a gun?” He’d reply, “It’s for the white folks, baby.” “Papa, why you get up so early?” “To keep up with the white folks, baby.” That’s from very young. That’s why I joined the Panthers.

I came from that idea of standing up, and I think a lot of people in Oakland have these southern roots and that whole connection with that idea of protecting your own people. We’re used to keeping and using guns because that’s what they did in the country. My grandfather always kept a gun; it was invisible, but it was always in the back of the car or up in the window in the back of the truck. They said in the South that they were for hunting, but he said it was for the white man. And it wasn’t for the white man who wasn’t bothering you, it was for the KKK and the others. And that’s what moved me into the Panthers.

So, that’s Elendar Barnes on why she became a Panther.

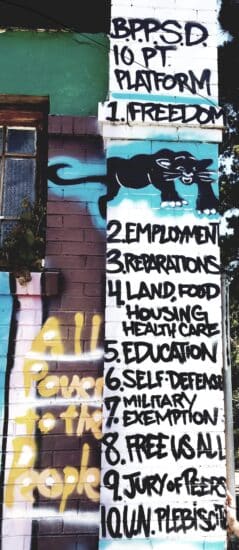

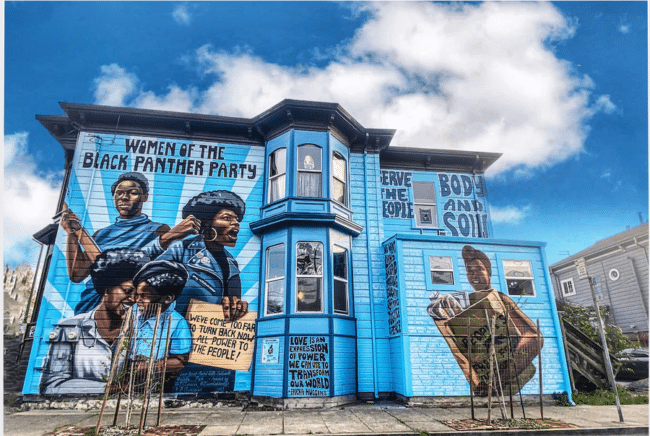

Mural depicting the BPP 10-Point Program, as seen on the side of Marcus Books in Oakland, California. Source: Josh Davidson

Phillips: In particular, they based their organization on a 10-Point Program, a platform some of you may be familiar with. Some of the points in the program and platform were the right to full employment, decent housing, quality education, an immediate end to police brutality, a right to a jury of your peers, and freedom from racial inequities, poverty, structural barriers. Much of the same issues that they were really advocating for during this period we’re still fighting for right now.

They were influenced by revolutionary thinkers such as Malcolm X, Queen Mother Moore, Frantz Fanon, and others. As the Panthers spread nationwide and internationally during this time, you had the Vietnam War going on, you had African liberation struggles. Hundreds of women joined the organization and they saw themselves as part of a global movement, and they contributed to one of the most powerful attempts to create a more just world.

Spencer: I hope that people in the audience have seen images of the Panther women. Those images are so powerful. I hope that you’ve had a chance to really just see those images of Panther women in photographs or in artistic representation, because the arts was one of the ways that the Panthers really delivered their political message.

Their newspaper, The Black Panther, created in 1967, grew to be one of the most popular alternative newspapers. It really delivered their message around the country and around the world. They used the pages of their newspaper as a canvas. It’s important to know that the women served as graphic artists creating these images.

A collage of Black Panther newspapers, as seen at It’s All Good Bakery, the original Panther office in Oakland, California. Source: Josh Davidson

So, I want to talk a little bit about the women who created some of the images and then look at some of the images and the women who were in the images and how Black women played such a pivotal role in carrying the Panther message, so to speak.

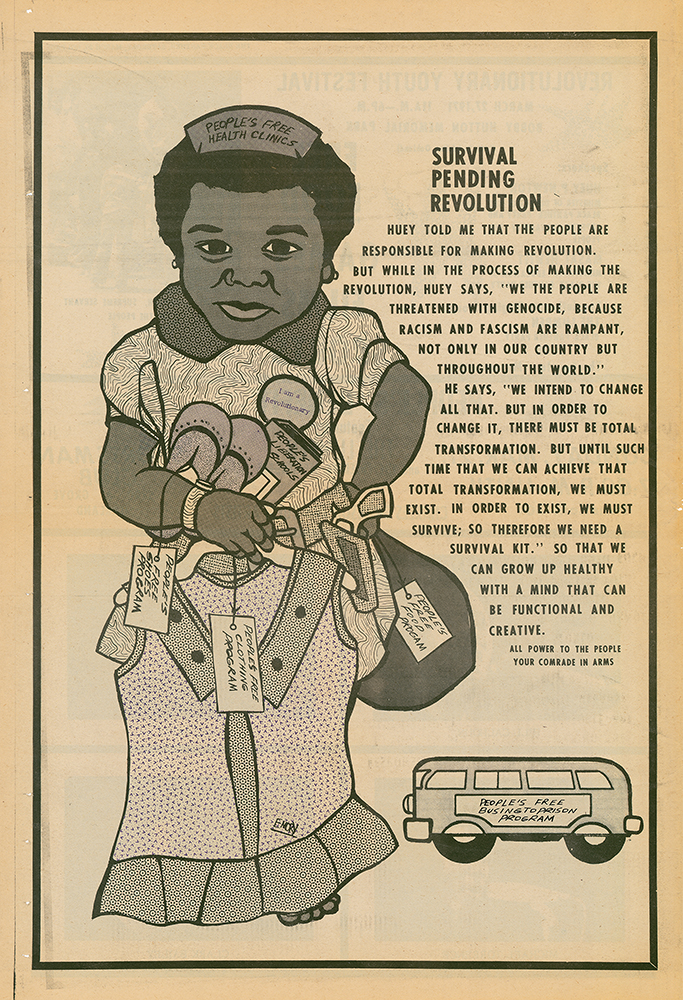

[Tarika] Lewis was not just the first woman to join the Black Panther Party, she was also an artist. Her drawings use sharp and rounded angles to depict Black men and women with intense beauty. She signed her pieces Matilaba. Gayle Dickson was also another Panther artist who created artwork in the Panthers under the name of Sally. Her style carried a sense of realism, where women’s authenticity was celebrated, especially in urban contexts, and they were shown in their everyday environments. Emory Douglas served as the Panther Minister of Culture, creating world famous images of struggle. I know you’ve seen those women who were at the center of many of his pieces.

Let’s travel back to the Panthers era and look at two of his pieces which center Black women.

Phillips: At this time, I want to have everybody take a look at the first image and I want you to draft what meaning does this draw for you. I am going to just read a couple of comments in the chat box. I’m going to have you take some time if you can just go ahead and write some comments in the chat box. So, I’ll just read a couple of them: self sacrifice, collective struggle, the personal is political, warrior reclamation of control by Black women.

I want to point out some of the photos on the wall — and so you see a photo of Ericka Huggins, Bobby Seale, Huey Newton at the time — these were political prisoners who were in the midst of a trial for a crime they did not commit. So, in a way there is a tribute to the political prisoners at the time. And you can see the image is really talking about poverty and the way in which she is really combatting poverty at the center with the rats.

Spencer: The very bottom of the image has language from the Panthers’ 10-Point Program, which says, “We want decent housing fit for the shelter of human beings.” It’s important to note that the woman is at the center of the image fighting back against rats, against poverty, against depression. The presence of rats and rundown housing has been well documented and is a continuing reality. It is these conditions and the reality of repression that prompted the Panthers to expand their community survival programs in the 1970s.

Phillips: The second image reflects the growth of the community survival programs and in the picture Emory Douglas centers community programs such as the Free Clothing Program, the Free Shoe Program, the Free Food Program, the Bus to Prison Program, the free health clinics and the People’s Liberation Schools. The commitment to the Party’s community programs are represented by a Black woman with clothes, shoes, a hat, the Panther newspaper, her purse, earrings, and a gun in tow.

Spencer: It really represents the continuities and changes in the Panthers’ political program in the body of a Black woman. Emory Douglas is reminding audiences that revolution was not just one thing. Then, as the Black Freedom Movement evolved in the 1970s and the terrain of struggle shifted, the Panthers would focus on their survival programs. This idea of survival pending revolution was a shift in the Panther strategy, but also represented these continuities, and the Black woman was centered as the vehicle for communicating this particular message. And this particular image and the one before this can do a lot of work in the classroom.

Phillips: I want to shift to thinking about the impact of Panther membership and the way in which Panther membership had on these young women, and the impact that they had on the work of the Panthers. Women often joined the Black Panther Party in high school and in college. Many Panther women balanced motherhood with the daily responsibilities of community organizing.

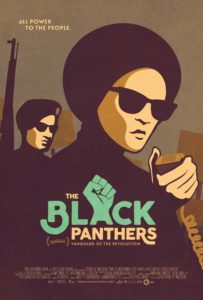

We’re going to show a brief video of Stanley Nelson’s documentary Vanguard of the Revolution [see trailer below]. In this video, you see Phyllis Jackson really talking about the way in which women balance motherhood with the daily responsibilities of community organizing. Phyllis Jackson played a major role in the Panther success of mobilizing thousands of votes during the electoral campaigns of Elaine Brown and Bobby Seale.

We’re going to show a brief video of Stanley Nelson’s documentary Vanguard of the Revolution [see trailer below]. In this video, you see Phyllis Jackson really talking about the way in which women balance motherhood with the daily responsibilities of community organizing. Phyllis Jackson played a major role in the Panther success of mobilizing thousands of votes during the electoral campaigns of Elaine Brown and Bobby Seale.

“I was in labor, cooking breakfast for the breakfast program, so I was between contractions flipping pancakes.” “I would spend all day answering the phones, even after I had my son when I came back to work. I used to have him jumping up and down on my lap (he was really heavy), but he just wouldn’t stop crying, as I’m answering the phone.” “You name it, I cleaned freezers with a toothpick.” I’d answer the phone, “The Black Panther Party national headquarters, how can I help you?”

“Dear Huey, when I joined the party, I was thrilled about becoming part of an organization that believes in the equality of men and women. It bothers me that there are brothers who still view women as sexual objects. We should have no men in the Black Panther Party who feel this way. Or women for that matter.”

“One of the ironies of the Black Panther Party is that the image is the Black male with the jacket of a gun but the reality is the majority of the rank and file by the end of the 1960s are women.” “Everybody knows all the people don’t have liberties, all the people don’t have freedom, all the people don’t have the justice, and all the people don’t have power so that means none of us do.” “The Black Panther Party certainly had a chauvinist tone, so we tried to change some of the clear gender roles so that women had guns and men cooked breakfast for children. Did we overcome it? Of course we didn’t. As I like to say, “We didn’t get these brothers from revolutionary heaven.”

History remembers the high profile names. The names that I recounted might be names that you have heard before, but I hope that during the course of our presentation that we’ve given you names you’ve heard before, but also names that maybe you haven’t heard before. I know that there are probably Panther women listening and in the audience today who can tell their own stories, as well. So we have other stories to tell.

Phillips: For example, Frances Carter — who was incarcerated in New Haven, Connecticut with Ericka Huggins — recounted the maltreatment of Panther women incarcerated with her. I just want to give a quote, which is from some of my work.

We are isolated in Niantic State Prison for Women. When we go to court, we are escorted by two state troopers in front and two state troopers in back. Mail is censored; it takes sometimes 15 days for it to get from one place to another. This demonstrates the high surveillance and the punitive measures such as isolation that women experienced who were identified as political prisoners because of their identity as a Black Panther Party members.

Spencer: From the first woman that supported the founding of the Black Panther Party — from community mother Ruth Bedford, who was an elder in the community who supported the Panthers, who carried their message, who very famously made the curtains for the first office in Oakland, California, to the first handful of women that opened the doors to people like Kathleen Cleaver, communications secretary and the first woman on the Central Committee, to women like Barbara Cox and Charlotte O’Neil, who traveled to Algeria as part of the Panther international section, to women like Audrea Jones, who held the Panthers health activism in Boston, to Ericka Huggins, the last director of the Panthers’ Oakland Community Schools — women really transformed the Black Panther Party in unforgettable ways.

[breakout rooms]

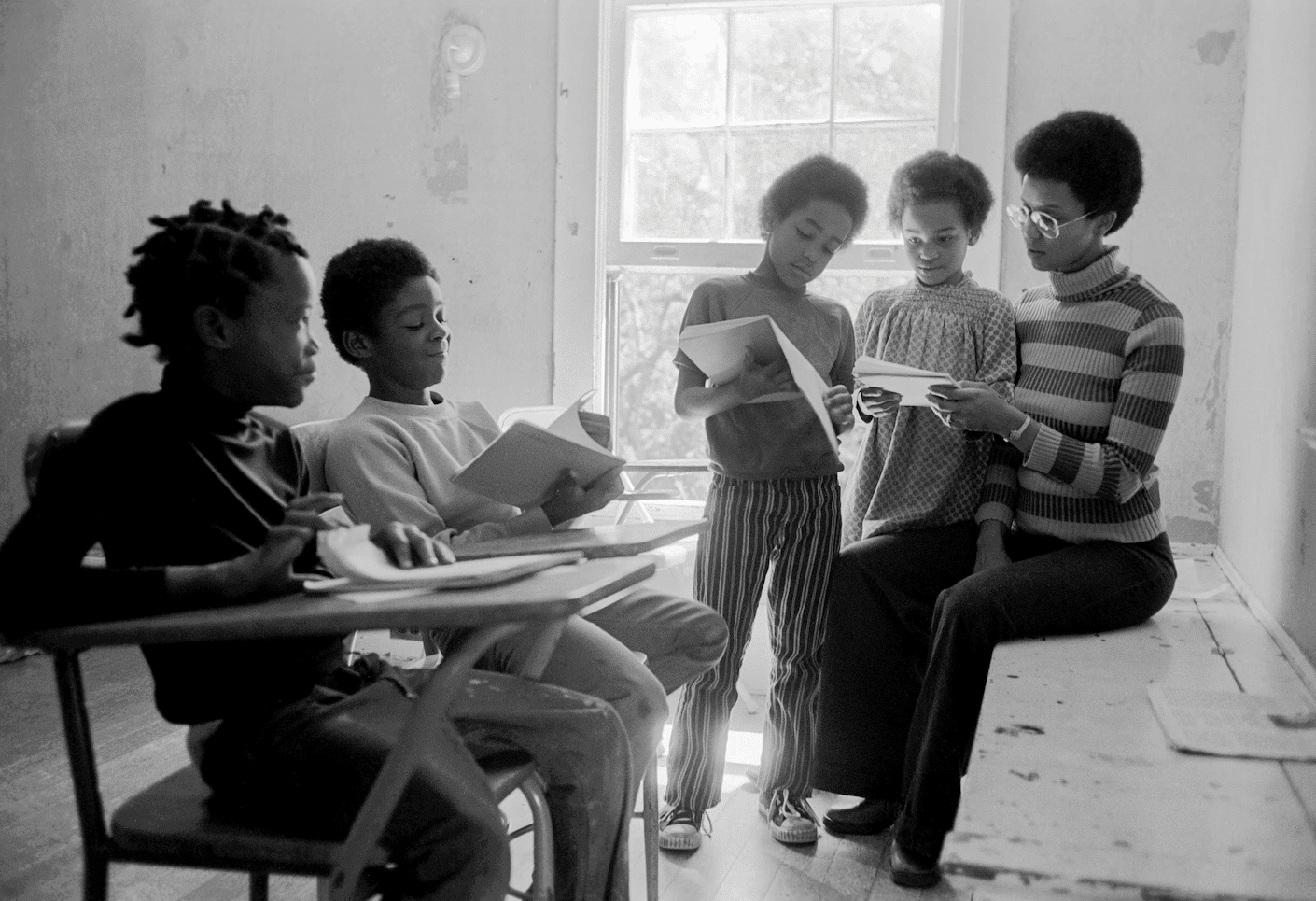

Spencer: Maybe we can start out by just talking a little bit about the Panthers in education, since we do have so many educators, and just thinking about the Panther school. Mary is doing some amazing work on the Panther school and Ericka Huggins, who did many amazing things as a member of the Black Panther Party, including helming the school for many years. So Mary, do you want to start off the conversation, and then we could just bounce back and forth?

Phillips: I don’t know how many people are familiar with the fact that the Black Panther Party did have their own school, the Oakland Community School. It was the last community survival program. It was an elementary level institution. It became, like I said, the Panthers’ longest running community survival program. It initially started as the Intercommunal Youth Institute in 1971, a homeschool safe haven for children of the Panthers due to the FBI’s COINTELPRO harassment that many what I call “Panther cubs” were experiencing. But by 1973, 1974, the Intercommunal Youth Institute evolved into the Oakland Community School with an enrollment of 50 children.

Phillips: I don’t know how many people are familiar with the fact that the Black Panther Party did have their own school, the Oakland Community School. It was the last community survival program. It was an elementary level institution. It became, like I said, the Panthers’ longest running community survival program. It initially started as the Intercommunal Youth Institute in 1971, a homeschool safe haven for children of the Panthers due to the FBI’s COINTELPRO harassment that many what I call “Panther cubs” were experiencing. But by 1973, 1974, the Intercommunal Youth Institute evolved into the Oakland Community School with an enrollment of 50 children.

I think what’s so beautiful about the Oakland Community School is the way that they taught their pedagogy. Students came from a variety of social and economic backgrounds. Most were from poor working class backgrounds. In existence for almost ten years, that administration utilized culturally relevant pedagogy, which I think is really critical, and which students can see themselves in the material in their history. Their culture was reflected in the classroom experience. And what I love about the Oakland Community School is how they embrace this idea of whole body education. That’s when they take into account the mental, the physical, the emotional, the abstract, the creative intelligence. They really try to fulfill all of these needs and all of the different aspects of the young child.

They also integrated restorative justice. They had a justice board, which was run by a small youth committee, and these young children would address any kind of harm or concerns on their own and come up with a mutual agreement. So, they learned how to take accountability, community building initiatives, how to work through their differences (which is critical), and they would do this with no adults in a room. They were given the skills to do this and they were committed. When we talk about restorative justice, it works in a way where no one is shunned, no one is stigmatized, as opposed to criminal justice system where that happens. So students learned valuable life skills, they listened attentively, they problem solved.

Another thing is they practice yoga as a form of discipline at the school today. It’s really cutting edge and very forward thinking in the kinds of strategies of learning that they implemented in the school. That’s just a little taste of why the Panther school was so popular. They had parents with unborn babies registering for the school, they won tons of awards, and it was to be a model institution in Oakland.

Spencer: Thank you, Mary. I encourage everyone to learn about the Oakland Community School. There are a lot of great resources that are out there about the school. There’s even a wonderful short video that’s available on YouTube [see below], and there’s a wonderful documentary in production, so you can learn more about those. We’ll be sending around some information about content after the fact.

So, how to get around that. This is a very real barrier that’s there, in terms of centering the Panthers in the curriculum. But one thing I think is very clear when you look at the story of the Black Panther Party is that there’s something very central to how they connect to all elements of U.S. history in this time period. Their story is a very American story. The story of housing and displacement; the story of migration post World War II; the story of political organization; the story of radicalization; the ways in which they mobilize their connection to the Great Society programs and the reform movements of the 1960s; their connections to a global revolutionary movement in the 1960s; their connection to the growing Vietnam War. These are ways you can centrally connect the Panthers to all of the other elements that are going on in this time period, whether it be the counterculture, whether it be the U.S. war in Vietnam, whether it be the women’s movement, whether it be the mainstream Civil Rights Movement. To think about the Panthers as connected to those movements is very central.

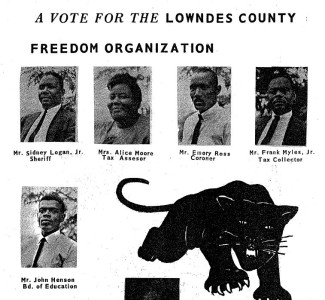

Candidates from the Lowndes County Freedom Organization.

We started out by telling you that the Panthers were one of many Black Panther Parties influenced by the Lowndes County Freedom Organization, which was a program that came out of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, SNCC. That is the place to start with thinking about the Panthers, and also to unpack this question of the violent 1960s. Where was the violence in the 1960s? Was it from these groups that were practicing armed self-defense or was it from the massive resistance to the Black Freedom Movement?

I know in our audience we have SNCC veterans, we have Panther veterans, we have Judy Richardson, who’s put together a great documentary on the Orangeburg Massacre. Right now, we’re walking into the wake of the Jackson State shootings. There are so many ways that we can think about re-centering the types of violence that activists faced in the 1960s, as they fought for their rights. And I think about ways in which we connect the Panthers to that legacy; instead of positioning them as so outside of the pale, but thinking about them as within that same tradition.

When we think about women in the Panthers, we have to think about women like Gloria Richardson, women who were part of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, women who stood up in all of these movements of the 1960s, who were influenced by the radical women who were coming out of the Vietnamese struggle, who were coming out of the Algerian struggle, who were part of a global upsurge, of a new way of thinking about women’s radicalism at the time. So, what was happening with the Panthers was not something that was unique and unprecedented. It was part of larger political and historical cross currents.

When we think about women in the Panthers, we have to think about women like Gloria Richardson, women who were part of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, women who stood up in all of these movements of the 1960s, who were influenced by the radical women who were coming out of the Vietnamese struggle, who were coming out of the Algerian struggle, who were part of a global upsurge, of a new way of thinking about women’s radicalism at the time. So, what was happening with the Panthers was not something that was unique and unprecedented. It was part of larger political and historical cross currents.

In this way, when we learn about the Panthers, we’re learning about U.S. history, we’re learning about global history, we’re learning about all of those standards that people like to put together, that oftentimes decenter Black and Brown people. But, in a lot of ways, if we sort of reconceptualize them, it’s important to think about that, and we have to move beyond the Malcolm versus Martin dichotomy. Even though I know that that is so much of how the Black Freedom Movement is taught.

But, luckily we have entities like the Zinn Education Project, Teaching for Change, and wonderful curriculum that’s produced by scholars, teachers, and archivists that allow us to think about how just one primary source can shift the conversation by showing the students that image. One image can change a conversation, and it can add some nuance to a story that they may think they already know. So, it’s about thinking about how you can use these primary sources, these images, these oral histories to tell another type of story.

Phillips: A couple of people have been asking a question about gender and sexuality in the Black Panther Party and I just want to answer that question a little bit. When we talk about non-gender, non-conforming, or folks that may have identified as gay or LGBT or what have you, one thing I want to point out is that the Black Panther Party worked through all of their differences. For some people, sexuality was fluid in the organization. Ericka Huggins always talks about how everybody brought their stuff to the organization, and we worked through those differences. But, it’s important to point out that the Panthers did make an effort to coalition with women’s liberation groups, feminist organizations, and LGBT identified organizations.

Huey P. Newton wrote an open letter in support of the gay liberation and feminist movements. That’s one of the most, I argue in his writings, powerful documents, because he not only calls out the homophobia that was existent at the time among some members in the Black Panther Party, but he says, “Look, we can’t do this work alone. We need to mobilize.” He says, “Look, folks that identify as LGBT are some of the most radical folks out there, and we need to mobilize with them and coalition with them. And we need to work through our own stuff.” His language in that letter, I’m not sure how many people have read the open letter, it’s very raw and unapologetic.

So, there were many coalitions that the Panthers did. Even if you look in the Panther newspaper, you will see interviews with leading members in the Black feminist groups at the time of them taking on issues that deal with sexism and gender politics. You see women really placing these concerns at the center and talking about these issues, particularly if you look into the 1970s you will see this. So, I want to make sure that I address that, as well.

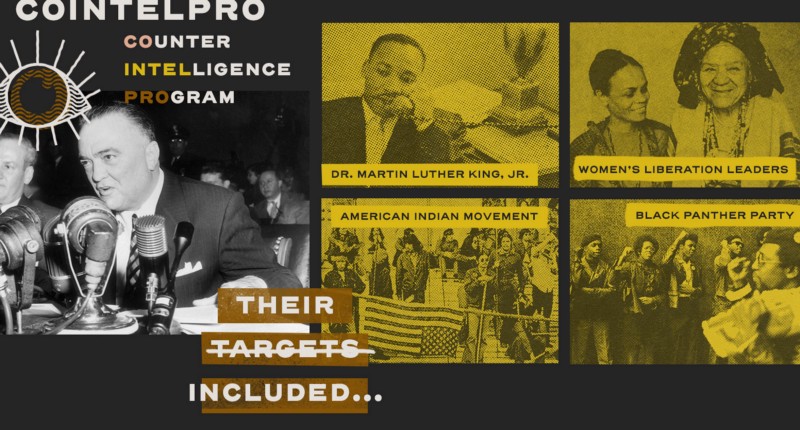

Spencer: I see some questions about COINTELPRO and the silencing of COINTELPRO in the larger history of Black radicalism, the history of women, and the history of this period, in particular. So, I definitely want to highlight that and say that, yes, we do have to tell those stories, this history of political repression in the 1960s, and before as well, to make a long history of political repression, and to connect that to the histories of political radicals and the history of the carceral state, the role of the police and their history in these United States.

Learn About Black Panther Party History, by Nicolas Lampert. Source: Justseeds

And what has that meant for Black dissidents? I think about the ways in which people like Dr. King were set upon by the FBI helped to frame how we think about the Panthers and COINTELPRO because they’re often seen as deserving of that because they were out here with their radical ideas. When you start with nonviolent activists being surveilled, harassed, and positioned into almost suicides, if you think about some of the more recent primary sources that have come out around manipulation of people like Dr. King and others.

Then, to go beyond that, what does it mean to not be a person whose name everyone recognizes, but to be going through that level of repression? What did it mean to be a rank and file member, a woman in the Black Panther Party, and be dealing with the daily surveillance? How did that impact your life, your activism, et cetera? These are the questions that we need to ask. And these are the ways that we need to think about accountability and telling this history and learning the story.

Because we know the stories, the flash points, the moments where male leaders were arrested and it made headlines, or people were assassinated in brutal ways, and it’s left a scar on history that maybe no one could ignore, even though they try. But we don’t know the daily grinding down, the ways in which COINTELPRO, surveillance, and repression really eroded the foundations of these movements in ways that push them into — or try to push them into — oblivion.

So, telling that part of the story is also central. And women, women and repression, women and motherhood, women and ideology, women in art, women in poetry, women and education, philosophy, women and nutrition, ideas about nutrition and parenting. All of these were discussed and central in the history of the Black Panther Party. All of these were radical ideas. But we don’t tend to think about that. When we think about the Black Panther Party, we have one narrow frame. If we broaden that then we’d really have a sense of what revolution looked like. The revolution that they were interested in making, anyway.

Phillips: I want to add the way in which, when we talk about repression and we talk about women in particular, I mean, much of my work looks at the way in which women were targeted during their incarceration and how they were framed, how they were plotted, how they were isolated, how they were beaten in prison, the lack of humanity and the resistance. What I have found in much of my research — and you can see this with Huey P. Newton — there were measures that these Party members put in place that helped them survive, so that they were able to come out of prison with their humanity intact, with their mind intact. Modes of resistance and the community building and initiatives that they did in prison — in a system that’s designed to really kill you, essentially, your mind and spirit — I think that’s useful for us to really take hold of. So absolutely, I mean, there are stories about political prisoners giving birth in prison and the horrific treatment, giving birth under this kind of duress. All of these other stories oftentimes don’t make it into the master narrative that we hear so often in public.

Spencer: I see some questions about change in terms of how the Panthers and Panther women have been portrayed. I’m happy to report an uptick in some amazing literature that has been produced. Our young scholars are on it in terms of the articles that are being written, the books that are coming out, really bringing so much complexity to the question of gender, sexuality, disability, politics, all different ways of thinking about the Black Power movement, the Black Panther Party, and gender and sexuality. There’s really so much more than there ever was before and I think it’s so important to connect what’s happening at and coming out from professional historians to what’s available to be used in classrooms by teachers. I think that’s where groups like the Zinn Education Project are the bridge that creates moments that can become curricular moments, where analyses and the National Endowment for the Humanities Summer Institute can be a place where teachers can go and find out about new interpretations, ways to rethink things, or to push back gently. Or to reframe things or to just pivot.

Sometimes it just takes that pivot, that seed to plant. I can’t tell you how many seeds teachers have planted that have come and sprung up years later, when I didn’t even realize it at the time. Just a question or someone that made me think twice about something I thought I was sure about, I thought I knew. I thought it was a truism, then later on I realized, okay, there’s another way of thinking about this. That’s what teachers can do. For every child whose mind is available to them to touch — whether it be through the screens that we’re forced into now or in person — that’s the power of being an educator.

So, I’m excited to see so many people out here and I’m excited at these connections. I think there’s more content than ever, and literature. People are reading books, fiction writers are on it telling these stories, as are poets. It’s a beautiful thing. Stoop kids can read the stories in their young adult literature and that makes it more even accessible than what’s coming from their teacher. Sometimes it’s coming from a book that they’re enjoying, they’re being entertained by, they’re laughing with, and they’re seeing themselves in, then it’s even better.

Phillips: It’s interesting because I’m teaching a course on the Black Panther Party and we — for those who don’t know, you should check out Alondra Nelson’s book that looks at the health clinics. It’s such an important book — and the Panthers have free health care clinics. The Panthers addressed sickle cell anemia, and they wrote all about this in their Panther newspaper, as well. I want to mention that a lot of the newspapers are online, so you can access those newspapers, as well. But, you could come and get free testing for sickle cell anemia. They were doing research on sickle cell anemia at the time at their health clinics. They were trying to demystify the medical system. They really wanted to be much more thorough and personal when you come to the clinic so you can understand what the person was saying, and they have volunteers coming in. And they didn’t always wear the coat because they were very strategic and organized with the health care clinics. They believed in it being free and assessable. And they believed in demystifying and really challenging the medical system.

Phillips: It’s interesting because I’m teaching a course on the Black Panther Party and we — for those who don’t know, you should check out Alondra Nelson’s book that looks at the health clinics. It’s such an important book — and the Panthers have free health care clinics. The Panthers addressed sickle cell anemia, and they wrote all about this in their Panther newspaper, as well. I want to mention that a lot of the newspapers are online, so you can access those newspapers, as well. But, you could come and get free testing for sickle cell anemia. They were doing research on sickle cell anemia at the time at their health clinics. They were trying to demystify the medical system. They really wanted to be much more thorough and personal when you come to the clinic so you can understand what the person was saying, and they have volunteers coming in. And they didn’t always wear the coat because they were very strategic and organized with the health care clinics. They believed in it being free and assessable. And they believed in demystifying and really challenging the medical system.

There’s a history of medical discrimination of Black and Brown bodies, and they were very aware of that. They were having this discourse in the newspaper about various issues that affect our bodies and what have you. So, it was important. With COVID-19 now, I have my students draw the connections. How do you imagine the Black Panther Party would respond to COVID-19 based on the thorough and detailed work the Panthers were doing in their free health care clinics? I have them look at all those archival documents that are available, that you can access, where you can actually see what their day-to-day lives looked like; the records, the memos. Audrea Jones was running the healthcare clinic in Boston.

Women’s hands were on all these documents, on all the community survival programs. We only know about a couple, but that’s part of the work that we’re trying to do, bringing more and more voices of women of the Black Panther Party to the center of the narrative.

Spencer: I want to highlight that there are so many Panther women who are available, people like Charlotte Hill O’Neil, who lives in Tanzania now but comes to the United States every year. She speaks to classroom groups, high schools, community centers, and other spaces where she’ll talk about the ways that she’s tried to bring the Panther model of survival programs and community programs that she was involved in. She’s brought that to where she lives currently in Tanzania. So the ways that they are bringing that model of community education, of grassroots empowerment, of running a children’s home, serving the community body and soul, and bringing that model to another context, and what that longevity has meant to Tarika Lewis, who is still out here. She’s an amazing musician and she gives talks.

Ericka Huggins, Kathleen Cleaver, Barbara Cox, there’s so many Panther women who are still out here. Sally Dickson, who we mentioned earlier, is an amazing Panther artist. You can look up her art as well. Almost all the names that we mentioned are with us, and I think at a time where maybe we’re more heightened and aware of the fleeting nature of life, we can look to these folks as our treasured sources. They are our primary sources. They are our gold. They are with us.

Finished in June 2021, this mural is the only public art installation in the world dedicated to the Women of the Black Panther Party (WBPP) and the 65+ Survival Programs they created. Photograph by Kerri Gaston. Source: West Oakland Mural Project

I get so many questions; on History Day students are writing to me, egged on by their teacher, to ask historians things. I think it’s nice sometimes to reach out to those folks who can tell how it was. Of course, they’re busy and all of that, but sometimes there are venues in which you can hear their wisdom. So, I always encourage people to just go and try to hear from the people who were directly involved. Sometimes when you hear a lot of stories and they’re so different — because Oakland was not Chicago, which was not New York, which was not Boston, which was not Detroit, which was not in Milwaukee. The Panthers were a nationwide expression but they had local nuances, as well. So being a woman in the Party was very different based on where you were, when you joined, who you were connected to, et cetera. Just to get those complexities, I think, it’s also important to reach out to those sources, as well.

Phillips: I think that’s a nice lead-in. Someone asked, “Did women actually feel equal in the movement?” It has a lot to do with what Dr. Spencer was saying. It varies by person, chapter, branch, region. For example, in much of my work in Detroit you will hear women, former Party members, saying, “Look, the experience I felt as a woman, I didn’t experience all of the kind of sexism that folks maybe experienced in LA or what have you.” So it’s not a blanket thing. All women didn’t experience the same degree. It really did vary by where you were located, who was in the organization, the gender makeup. It’s very complicated. So, I want to get away from the idea that a lot of people when they think of the Panthers and think of women, they just think sexism, and that is really not the case at all.

This interview was lightly edited for length and clarity. Find more on women in the Black Panther Party, including related lessons, books, and articles, in our class resources post.

Robyn C. Spencer is a historian who focuses on Black social protest after World War II, urban and working-class radicalism, and gender. In 2018–2019 she was Women’s and Gender Studies Visiting Endowed Chair at Brooklyn College, CUNY and she is currently an associate professor of history at Lehman College. She is the author of The Revolution Has Come: Black Power, Gender, and the Black Panther Party in Oakland and is working on two book projects. To Build the World Anew: Black Liberation Politics and the Movement Against the Vietnam War explores how and why the anti-imperialist struggle for Vietnamese independence became a rallying point for U.S.-based Black activists who were part of the freedom movement of the 1950s–1970s. She has also begun research on a biography of Angela Davis.

Mary Phillips is a proud native of Detroit, Michigan. She works as an assistant professor in the Department of Africana Studies at Lehman College, City University of New York. She was selected as a 2018–2019 award recipient for the American Association of University Women American Postdoctoral Research Leave Fellowship. Her interdisciplinary research agenda focuses on race and gender in post-1945 social movements. Her latest book, Black Panther Woman: The Political and Spiritual Life of Ericka Huggins, is the first and only scholarly monograph on the experiences of former Black Panther Party member and human rights activist Ericka Huggins.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn