By Ursula Wolfe-Rocca

By Ursula Wolfe-Rocca

Sam Wineburg, Margaret Jacks Professor of Education at Stanford University, recently published a new book, Why Learn History (When It’s Already on Your Phone), addressing the need to cultivate historical thinking in students. To publicize the book, Slate ran an excerpt critiquing Howard Zinn’s A People’s History of the United States, and the teachers who teach it. Wineburg writes that Zinn “speaks with thunderous certainty,” and that his “power of persuasion extinguishes students’ ability to think and speaks directly to their hearts.” Ultimately, says Wineburg, the book is dangerous because “Many teachers view A People’s History as an anti-textbook, a corrective to the narratives of progress dispensed by the state.” But in actuality, “A People’s History is closer to students’ state-approved texts than its advocates are wont to admit.”

Given the dangers Wineburg detects in how teachers use A People’s History in their classrooms, it is perplexing that his article offers not a single example of a real teacher, classroom, or lesson. The article opens, tellingly, with fiction, not facts. To establish A People’s History’s popularity, Wineburg describes its cameo appearance in Good Will Hunting and in an episode of The Sopranos. Zinn’s popularity (2 million copies of A People’s History in print) is one thing, but if Wineburg’s real concern is history education, one would expect to be taken into classrooms where Zinn is being taught; one would expect to encounter the teachers who are using the text; one would expect examples of students whose ability to think and reason has been compromised by their exposure to Zinn’s “thunderous” certainties. Yet, Wineburg’s readers get none of that. Nor do readers find any evidence of his claim that “For many students, A People’s History will be the first full-length history book they read — and, for some, it will be the only one.”

Well, I am a real teacher who teaches real students in a real classroom using real lessons that rely on excerpts from A People’s History. It is from this reservoir of experiential knowledge that I take issue with much of what Wineburg has written in his takedown of A People’s History and those who teach it. First, as Alison Kysia noted in her rebuttal to an earlier Wineburg screed against Zinn, he does not spend any time supporting his assertion that A People’s History is ubiquitous in U.S. classrooms. In my own high school history department, most teachers (sadly) use nothing written by Zinn. When I do encounter other teachers who use A People’s History, they, like me, use it alongside a variety of sources, primary and secondary. For some units in my U.S. history courses, I use as little as a couple of pages, for other units, I might ask students to read a whole chapter, and for still other units, I use none of the book. The idea that Zinn occupies an outsized or dominant place in U.S. classrooms is not an accurate description of the curricula and classrooms with which I am familiar.

(c) Rick Reinhard

Wineburg’s claim that teachers like me view A People’s History as a corrective is not entirely wrong. I do see Zinn as part of a long and valuable tradition of historians who explicitly challenged dominant, incomplete, and sometimes downright inaccurate narratives. Indeed, ongoing revision is at the very heart of historical analysis and scholarship. Black Reconstruction by W. E. B. Du Bois challenged the Dunning School’s decades-long racist mischaracterization of the years following the Civil War. Feminist history corrected centuries of patriarchal erasure of women’s lives and power. And A People’s History undermined the dominance of “a certain approach to history, in which the past is told from the point of view of governments, conquerors, diplomats, and leaders,” as Howard Zinn writes. So yes, when I have students read “We Take Nothing by Conquest, Thank God,” Zinn’s chapter on the U.S. war with Mexico, it is in part, to “correct” the narrative of that war students generally encounter in textbooks and other corporate curricula. In this narrative, the war with Mexico is elided into “Westward Expansion” or the Civil War, and given short shrift (in my school’s sophomore-level U.S. history textbook, American Odyssey, the war gets two paragraphs), as if it was inevitable that one-third of Mexico would be seized by the United States. Zinn’s account, on the other hand, is lengthy, offering space to the politics of slavery and expansion, but also to the anti-war movement, to the experiences of soldiers and immigrants, allowing readers to engage the discourse of the time through newspaper editorials, diary entries, and letters. Zinn’s 20-plus-page chapter insists upon the enormity — rather than inevitability — of the war, a correction I embrace.

(c) Rick Reinhard.

Students usually come to me with a basic definition of the historian’s work: to tell the story of the past. My curriculum — and that of other teachers I know — tries to complicate that. I seek to help students understand that 1) there is a contentious debate and dialogue among historians taking place over time and each text we consult contributes to that ongoing discussion, and 2) historians mobilize sources and make analytic moves that shape the meaning of the story we read. I teach students that historians make arguments and that any historical book, chapter, essay is just that: an argument about the past. One way to make this clear is to have students compare their district-adopted textbook with Zinn’s account. But Wineburg scoffs at this idea. He writes, “Pitting two monolithic narratives — each strident, immodest, and unyielding — against one another turns history into a European soccer match, where fans set fires in the stands and taunt the opposition with scurrilous epithets.”

When I bring the textbook and Zinn into dialogue in my classroom, I am not inviting students to judgment, but to clarity. I hope to arm them with the knowledge of how the sausage of historical writing is made, the way textbook writers, and all historians, make choices about what to say and how to say it, leaving the reader with a particular set of impressions and beliefs — an argument — about the past. It is true that one reason I teach A People’s History in conjunction with other texts is to surface different narratives of U.S. history. But my goal is not for students to accept one and to “jeer” the others. Nor, of course, do I want students to throw up their hands and say, “There is no truth!” When students inevitably ask, “Which one is true?” I say, “Let’s dig a bit deeper and see what we find.” We read widely, primary and secondary documents. We discuss. We write. We consider, again and again, what is the argument this author makes about the past and how do they make it? The point is not to coerce my students to accept one text as truer than another; the point is to equip students with the critical reading skills and historiographical fluency to enable them to see arguments that masquerade as simple accounts of What Happened.

Wineburg writes that his concern is not so much what Zinn says in A People’s History, but “the book’s interpretive circuitry,” which he asserts is “largely invisible to the casual reader.” Here, Wineburg seems to forget about teachers altogether, assuming we simply pour Zinn down the throats of our students, as opposed to actually, you know, teaching. Indeed, one could accurately say that a primary goal of my entire U.S. history curriculum is to enable students to identify the “interpretive circuitry” of all the texts they read, whether A People’s History or their textbooks or a post on Twitter.

A People’s History Is Not Just Another Textbook

A People’s History Is Not Just Another Textbook

And when it comes to this “interpretive circuitry” of Zinn’s analysis, it is dumbfounding that Wineburg completely ignores a crucial difference between A People’s History and standard corporate textbooks: Zinn does not disavow his own voice or power in shaping the history he offers; he makes it explicit. Zinn writes, “Thus, in the inevitable taking of sides which comes from selection and emphasis in history, I prefer to try to tell the story of the discovery of America from the viewpoint of the Arawaks, of the Constitution from the standpoint of the slaves…” He continues: “. . .this book will be skeptical of governments and their attempts, through politics and culture, to ensnare ordinary people in a giant web of nationhood pretending to a common interest.” Zinn makes clear his book will “emphasize new possibilities by disclosing those hidden episodes of the past when, even if in brief flashes, people showed their ability to resist, to join together, occasionally to win.” Finally, Zinn says, “That, being as blunt as I can, is my approach to the history of the United States. The reader may as well know that before going on.” Textbooks make no such disclaimer nor do they reveal the values, motivations, and interests driving their argument about the past.

Wineburg allows that A People’s History is full of stories that “acquaint students with a history too often hidden and too quickly brushed aside by traditional textbooks.” But he seems strangely uninvested in the necessity of such a project, as if writing bottom-up history and representing the experiences of traditionally marginalized groups is just another polemical trick. Wineburg writes, “Long before we could Google accounts of a politician’s latest indiscretion, Zinn offered a national ‘Gotcha.’” A book that seeks to center the voices of people of color, women, immigrants, and workers may indeed offer a rebuke to a country that has so often mistreated them, but that is not its purpose, nor the driving motivation behind those of us who choose to teach it. For me, A People’s History is one piece of a larger pedagogical stance toward inclusivity and representation. I seek out curriculum that surfaces the lives of everyone in our society because my students make up that society, and deserve to understand how they, and we, got to where we are today. Wineburg says we cannot enter “the past with a wish list,” but surely we can demand that our histories include a fuller spectrum of the human experience.

It was the belief in the necessity of providing young people access to a fuller account of the past that led to the creation of the Zinn Education Project (ZEP) more than a decade ago. Yet, in spite of the fact that the organization bears the very name of his nemesis, one wonders if Wineburg has ever looked at the lessons posted at Zinnedproject.org. He might be surprised to find that some ZEP lessons make use of A People’s History, some do not, and what unites them all is not a blind faith in the work of Howard Zinn, but an approach to teaching that emphasizes people — including those marginalized by both history and historical writing. Lessons like those addressing the Seneca Falls Convention, SNCC, the Dakota Access Pipeline and Standing Rock, the Tulsa Massacre, the Southern Tenant Farmers’ Union, or the incarceration of Japanese Latin Americans during World War II draw on and introduce students to multiple sources of information, and importantly, engage students in understanding and confronting injustice, past and present, from multiple perspectives.

Wineburg writes that A People’s History “substitutes one monolithic reading of the past for another, albeit one that claims to be morally superior. . .” I encourage you to read David Detmer’s dismantling of Wineburg’s accusation of monolithism, but I want to spend a moment addressing the question of moral superiority. Indeed, this is one place where Wineburg has it right. I do see histories that highlight women, workers, people of color, immigrants, and grassroots resistance as morally superior to textbooks whose pages drip with dangerous nationalism, glorify the already-famous and powerful, and that continue to marginalize the already-marginalized in sidebars and “enrichment” activities. To say I believe A People’s History to be a better kind of history does not mean I abdicate my role as educator, becoming a mindless automaton attempting to stamp Zinn onto the minds of my students. Yet, this assumption — that teachers do not or cannot teach Zinn and critical thinking — is at the heart of Wineburg’s critique. He disrespects teachers and offers zero evidence that such disrespect is warranted.

Wineburg’s disrespect extends to students as well as teachers. All good teaching begins with respect for young people, a belief in their intelligence, curiosity, and ability to learn. But Wineburg paints a picture of young people who are overly emotional, dangerously naïve, and vulnerable to Zinn’s overwhelming “charisma.” He writes,

Zinn’s undeniable charisma turns dangerous, especially when we become attached to his passionate concern for the underdog. The danger mounts when we are talking about how we educate the young, those who do not yet get the interpretative game, who are just learning that claims must be judged not for their alignment with current issues of social justice but for the data they present and their ability to account for the unruly fibers of evidence that jut out from any interpretative frame. It is here that Zinn’s power of persuasion extinguishes students’ ability to think and speaks directly to their hearts.

What a strange notion that one’s ability to think is compromised by one’s ability to feel. In my own experience, it is often the opposite. The engagement of my heart leads to the devotion of time and intellectual labor toward knowledge, understanding, and expertise. Wineburg simultaneously insults teachers — implying that they simply turn their students over to Howard Zinn’s charismatic prose — and students, whose emotions will inevitably stifle their critical thinking.

The Spelman Error

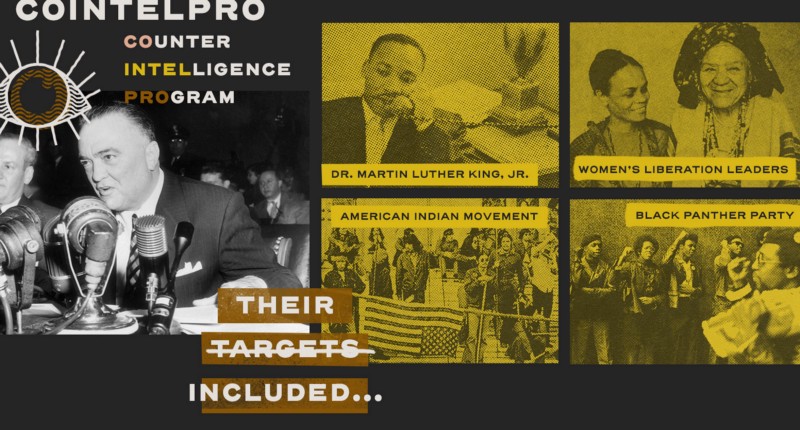

Alice Walker (top) and Marian Wright Edelman (bottom) were among Howard Zinn’s students.

Inadvertently, Wineburg offers a glimpse of this disrespect for students in a section of his article detailing some dramatic moments in Zinn’s life. The function of this biographical sketch is not altogether clear, except as a foil for this statement: “But this is not a story about Howard Zinn, the man. It’s about Howard Zinn, the curriculum.” The sketch Wineburg provides is instructive in its inaccuracy. He writes, “After receiving his doctorate in history from Columbia, Zinn went to teach at Spelman, a historically Black women’s college, but was fired after he organized the college women (Alice Walker and Marian Wright Edelman were among his students) to enter the ‘White Only’ branches of the Atlanta Public Library. . .” In fact, Zinn did not organize the “college women,” they organized themselves. As Zinn explains in his autobiography, You Can’t Be Neutral on a Moving Train,

Sometime in early 1959, I suggested to the Spelman Social Science Club, to which I was faculty adviser, that it might be interesting to undertake some real project involving social change. The discussion became very lively. Someone said, “Why don’t we try to do something about the segregation of the public libraries?” And so, two years before sit-ins swept the South and “the Movement” excited the nation, a few young women at Spelman College decided to launch an attack on the racial policy of the main library in Atlanta.

In Zinn’s telling, he is certainly an important part of the story, but it is a conversation, dialogue between empowered students and a supportive professor, that results in the decision to act. The precise action taken is selected and designed by students. Wineburg, on the other hand, assigns outsized influence to Zinn in the actions of the Spelman activists, robbing them of their agency and power. (He also mangles the chronology, as Zinn was not fired as a result of these events, which took place in 1959, but in the summer of 1963.)

Wineburg’s attempted takedown of A People’s History also assumes teachers and students are passive victims of Zinn’s “charisma” and “thunderous certainty” — that Zinn is “the curriculum.” Just as there was no room in his account for the Spelman women to think for themselves, Wineburg cannot seem to fathom skilled teachers and questioning students capable of engaging Zinn, and even learning from him, without losing our ability to think. Wineburg argues that A People’s History offers a “history of unalloyed certainties,” that “abhors shades of gray.” But it is Sam Wineburg who cannot tolerate complexity and shades of gray. His analysis has no room for Zinn’s statement “I did not pretend to an objectivity that was neither possible nor desirable,” no room for teachers who use Zinn, but not exclusively, no room for students who mobilize both heart and mind in analyzing the past, and no room for curricula that manage to amplify marginalized voices without “turning history into a European soccer match.” In his myopic condemnation of Howard Zinn’s book, Wineburg has ignored the experiences of real teachers and students, ironically imposing a Great Man theory of curricula to what is actually a people’s work.

Help Us RespondIn the face of attacks like these, teachers turn to the Zinn Education Project to respond and to redouble our efforts to provide people’s history lessons for middle and high school classrooms. We do not receive corporate support. Instead, we depend on individuals like you. Let people’s history teachers know they have your support with a donation today.

|

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn