On September 16, 2024, historian Kellie Carter Jackson joined Rethinking Schools executive director Cierra Kaler-Jones and editor Jesse Hagopian to discuss her book, We Refuse: A Forceful History of Black Resistance. This session kicked off the 2024–2025 season of our monthly Teach the Black Freedom Struggle online classes.

Jackson discussed countless ways African Americans refuse and resist white supremacy. She reframed popular narratives about revolution, explaining why the American Revolution was not revolutionary, and how the Haitian Revolution and the Reconstruction era had more liberatory and revolutionary outcomes. (Listen to an excerpt in the audiogram below.)

The most important thing I learned today was how Black people have refused and resisted by asserting their humanity, building joy, and continuing to live freely.

This class was mind-blowing!

I really appreciated how Dr. Jackson incorporates joy into how we teach. I struggle with figuring out how to show that history often doesn’t have a happy ending but there are ways we can still uplift students.

I came this evening feeling tired and drained, but I’m leaving feeling full and inspired.

Our people were able to accomplish so much because they protected and uplifted each other. We need to continue with the new generation because the fight for liberation is not over.

I was riveted and deeply moved by the histories that Kellie Carter Jackson shared. The focus on refusal is so powerful as a theme in history and education.

Event Recording

Recording of the full session, except for the breakout rooms.

Transcript

Click below for the full transcript with resources mentioned in the discussion.

Transcript

Jesse Hagopian: I’m happy to welcome Kellie Carter Jackson. She is the Michael and Denise ‘68 associate professor of Africana studies and the chair of the Africana Studies Department at Wellesley College. She is the author of We Refuse: A Forceful History of Black Resistance and Force & Freedom: Black Abolitionists and the Politics of Violence. I absolutely loved this book, and I’m really excited to dig into it with you this evening.

Cierra Kaler-Jones: Yes, thank you so much for being with us. We’re looking forward to this conversation. The book cover is beautiful, it is fabulous, and the contents of this book are just incredible. We want to start by asking you about your ancestors’ refusal and how you came to this concept of talking about refusal. In the book you share this story of your ancestor who was denied medical care leading to a lifelong limp. Can you talk about this story and how this personal history shaped your understanding of resistance and your interest in writing this book?

Kellie Carter Jackson: First of all, thank you so much for having me. This is like such an honor. I’m a huge fan. A lot of my fellow academic friends have done this class before and it’s just really special to be asked, and to have people that are like invested in my work. I tell people all the time, every author just wants to be read. That’s it. To be read. So it feels really good to be read.

The story We Refuse actually opens with a story about my great grandmother Arnesta. When Arnesta was 9 years old, she stepped on a rusty nail, and we’re not sure what happened. We probably think that she got tetanus, but she got a really bad infection and was almost to the point of death. Her mother, Mary Bullard, was frantic because Arnesta was a child and she was her only child. So she took her to the only doctor she knew, a white man who lived in a big house on the other side of town.

Basically she says to him, “Will you help my daughter?” And this white doctor says, “Sure, I’ll help her on one condition. After I do this, she has to come live with me and work for my family for the rest of her life.” She’s 9 years old. I just can’t imagine that kind of proposal. And because it was 1915 in rural Alabama, her mother, Mary Bullard, agreed. She didn’t want her daughter to die, and she thought, “Well, maybe this is better than death.” My great, great grandmother — whose name is actually lost to history, I don’t know her name, but we suspect it’s Mary as well, but we’re not sure — she picks up our Arnesta and she’s like, “Absolutely not. No way, not on my watch. We refuse,” and takes her back home and gives Arnesta every single concoction that she can come up with. I’m not exactly sure what she used but she healed Arnesta. She saved her life. But as a result of the healing, my great grandmother walked with a limp for the rest of her life.

I talk about how she was really imprinted by this violent racial act of refusing to care for her. I talk about how oftentimes that’s what it means to be Black in America. We can refuse bondage or we can limp. Those aren’t great options, you know what I mean. It’s not great options to die or to be in bondage or to walk with a limp. But what I love about that story is that my great, great grandmother refused the metaphorical fork in the road. She carved out a space for her granddaughter to survive that had nothing to do with the doctor and had nothing to do with death or slavery.

The reason why I started with this story is because I asked my mom why our great grandmother walked with a limp. She told me this story and it just set off a whole bunch of questions. If these were her options in 1915 — 50 years after slavery had been abolished these were the detestable options in front of her — how might we think about our own refusal and the options that are presented before us in our own lives — maybe not as stark, or maybe not as dire — requiring us to refuse proposals and to refuse white supremacy. So that’s where the book started.

I think that oftentimes in history we talk about resistance a lot, but for me resistance is the how of fighting back against white supremacy. But refusal is the why. And I think that for me, I see refusal as not just a no, but never. Never. And that’s why it was so powerful for me to start there, to say, “Yes, resistance matters and we’re going to talk a lot about it.” But we’ve got to get to refusal first because that’s the why.

Hagopian: I love that. I really appreciate how you wove in your family story all throughout the book to ground it in your own experience. My dad recently discovered which plantation our family had been enslaved on in Mississippi and we had a chance to go down there this last spring. We even met descendants of the family that enslaved our family and had lunch with them. I still don’t know how to describe that or what to say about it. I’m working on that. But I was inspired by your storytelling about your family history to think about how to explain it.

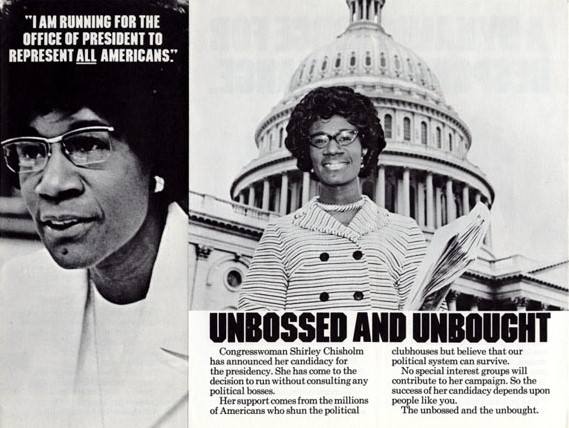

In the introduction you write, “Refusal is Black culture. It is our anthem, a mantra, a way of being present in the novelty and genius of our vernacular, in the newspaper, and the literature we create to tell our stories, in the drum, the banjo, and bass that permeate our music and vocals that refuse to be timid, deluded, or replicated. It is present also in our willingness to welcome, forgive, be hospitable, and care. We refuse to build ourselves up.” I just absolutely love the language, the emotion, and the sentiment that you put forward there. Can you explain why you titled the book We Refuse and how you see this idea of refusal playing out in today’s ongoing struggles for racial justice?

Jackson: That’s a good question. I had a horrible title at first. At first it was like Violence in Four Parts or something like that. My friend was like, “What? That sounds like a play. What is that?” And I was like, “Okay, that’s not good.” Even my editor was like, “We need a better title.” I was on vacation and I was trying to think the whole time what should I call this book. I started thinking about refusal because I talk about refusal so much in the book, but I didn’t want it to be I Refuse and I didn’t want it to just be Refuse.

I wanted to call back to the collective and We Refuse is really this mantra, this idea, that I think is pertinent in not just Black culture, but native American culture and Latino culture, and a lot of cultures of oppressed people and marginalized people where it’s like, “No, we are not taking this lying down. We will fight back.” I love the idea of refusal because it’s not a polite “no.” It’s not a “please.” When you refuse something you are emphatic that it is not there. There’s no politeness and well manners about it. Sometimes when we talk about white supremacy and we talk about combating it, sometimes I’ve gotten really frustrated. And that’s where the origins of this book came from.

I feel like we talk about resistance like are you going to be violent or nonviolent, like these are the options in front of you if you’re going to be like Malcolm X. Is it going to be “by any means necessary” or is it going to be like MLK? Are you going to march and protest? But are you going to be nonviolent? That’s always what it comes back to, and I just wanted to have a much more expansive way of thinking about Black resistance. If my students, if Gen. Z, has taught me anything, it’s that binaries do not serve us very well, that these dichotomies, these limited boxes that we put ourselves in of violence or nonviolence, does not explore the fullness of Black resistance.

We are not just throwing Molotov cocktails or forgiving people when they harm us. Those are not the options. So, by looking at refusal I get to look at a lot of different things. The book is made up of five chapters — Revolution, Force, Protection, Flight, and Joy. This is not an exhaustive list; I feel like I could have added more chapters if I had time. But I wanted to look at all of the different ways that Black people refused, and that refusal looks so different. It looks different for the individual as it does for the collective. It looks one way for women and Black mothers than it does for Black men. But, I thought it was just so important to encapsulate that.

I,n 2020 there were all these memes, trash memes, going around like, “Be careful. I’m not my ancestor,” and I was like, “What’s that garbage? Do you not know your history? Do you not know that Black history is a history of refusal? We’ve been doing this for centuries; what you are doing is not new.” So, as a historian, I like to tell people stories. That is how history is my weapon. It’s my way of talking about how people have refused.

Hagopian: That’s beautiful.

Kaler-Jones: Wow! That’s so powerful. I love the intentionality behind the language, all of the iterations of the book title and coming to refusal. It makes me think about one of my mentors, David Johns. He always told me that no is a full sentence, period, full stop.

Jackson: Yes, I love David.

Kaler-Jones: You talked about it in different sections of your book, so we wanted to talk a little bit about revolution. Now, this question, I think, is really pertinent given the conversations happening online in light of the presidential election and the debate. It’s so important that we lift up Haiti. In the book, the Haitian Revolution is “a radical reimagining of what freedom could be — a world without slavery, a world where the oppressed could claim their humanity.” You also contrast the Haitian Revolution to what’s called the “American Revolution,” arguing that it should be more accurately described as the American War for Independence. So, can you talk a little bit about that distinction, especially for the teachers on the call, and talk about what the Haitian revolution teaches us about the potential for revolutions to create systemic change rather than just incremental progress.

Jackson: Absolutely. This may sound like fighting words, but the American Revolution was not revolutionary. It just was not. Nothing changes for Native Americans; life is worse; nothing changes for Black people; life gets worse; slavery persists for another 100 years after 1776; nothing gets better for women; nothing gets better, really better, for poor white people, either. It’s not revolutionary. What it does is, it replaces a foreign leader with a local one. But for the most part, a lot of those power structures are still in place.

When I think of a revolution, for me, it’s not just this apocalyptic, we ride at dawn, like this very scary thing. It is like replacing a broken system, a bad system, with a better one, with a just one. So when I think of revolutions, to me, you can’t talk about a revolution without the abolition of slavery. So, America has its revolution but it doesn’t free its enslaved. France has its revolution, it does not free its enslaved. Haiti is the only one that says, “Yes, we’re going to overthrow a colonial power and we’re going to abolish the institution of slavery.”

And not only that, but when you think about the revolutions that take place in Latin America, when Simón Bolívar is popping off his revolution he goes to Haiti. He’s like, “Hey, I need help.” And they’re like, “Okay, we’ll help you. We’ll give you guns and we’ll give you soldiers on one condition — that you abolish slavery throughout all of Latin America. South America has Haiti to thank for its freedom in a lot of ways. We don’t talk about how liberation should liberate other people, that it shouldn’t just be something that is for one group of a select few people, but for everyone.

So, Haiti to me is just the starting point for a lot of places. I think we don’t talk about Haiti enough, and part of that is because of racism and anti-Blackness. The short answer is anti-Blackness and a refusal to see that this small island nation — smaller than the state of Vermont and more mountainous than the state of Vermont — managed to overthrow a European power and do what the other European powers could not — abolish slavery; not have to subsist off of enslaved labor. That, to me, is just everything. So I write about Haiti. I also write about Guadeloupe, this small island that was also part of France that does get freedom, then gets re-enslaved again, and then gets freedom later, like what these delays look like.

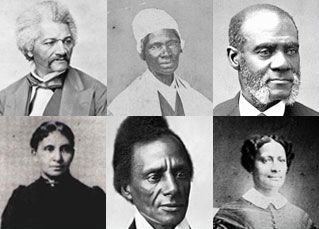

But in the American context, I think it’s important to say that revolution does come to America. But, one of the arguments I make is that if America was conceived in 1776, it wasn’t born until 1865. I really see the birth of America as the conclusion of the Civil War. So, when you think about what happened after 1865, you have not just war, [you have the abolition of slavery; you have the granting of citizenship with the 14th Amendment; you have the granting of suffrage with the 15th Amendment for Black men. Reconstruction brings the first universal education system. We all have public education because of Reconstruction. We all have the first public health departments because of Reconstruction, because so many people died in the Civil War and there were so many diseases that it was important for the country to have its own first public health departments and sanitation departments. There’s so much that comes out of Reconstruction that is revolutionary.

There are revolutionary things that are happening. There are over 1,500 Black elected officials during Reconstruction — that’s insane to me. Nowhere else other than Haiti do you get an enslaved person who’s now serving as a U.S. senator or a congressman within less than a generation — that someone like Robert Smalls, a Black man who’s enslaved in South Carolina, gets his freedom, and then goes on to serve in Congress — happen anywhere else. That’s revolutionary. So yeah, we do have a revolution in America, but the hardest part of getting a revolution is sustaining it. That is the hardest part. Haiti has had the hardest time sustaining its victory. Black people in America have had the hardest time sustaining their victory. And I think that’s because a lot of times we think that revolution is the ending point. No, it’s the starting point. It’s where you start, it’s where the story begins. This is the beginning of our work, and that work is ongoing and really never ending, because the moment you take your foot off the gas in terms of liberation then that injustice is right around the corner.

Hagopian: No doubt. What wonderful lessons you drew out of that. We’re seeing it again today with U.S. imperialism attacking Haiti — instability that they just chalk up to Haiti being poor — and understanding the way that the U.S. built blockades against Haiti and impoverished the country. This is where knowing something about history is so important, and you just broke it all down in the book.

In the chapter you title Protection, I love this chapter and I learned something brand new that I’d never heard of before, that I really appreciated. You discussed the Lancaster Black Self Protection Society that I hadn’t heard of and was really inspired by. You highlight the essential role that Black women played in organizing and leading efforts to protect their communities. I’ve been studying more and more the role of Black women in both armed self-defense and all kinds of areas. But I hadn’t come across this story before. It was great, and this was fascinating history that was kept from me and my schooling. I was hoping you could talk more about the Lancaster Black Self Protection Society and the historical role of Black women in armed resistance.

Jackson: First, I love the word that they’re using, the word “Black.” In the 19th century, the Black Self Protection Society, it’s just amazing. This story is one of my favorite stories to tell. It’s actually a story I also talk about in my first book, Force & Freedom, too. I’m going to try to keep it short because I don’t want to have too many long answers. But basically, William and Eliza Parker are Black, they are fugitives, they are living in Christiana, Pennsylvania, which is right on the border of Maryland — the slave state of Maryland — and the Free State of Pennsylvania, and they make their house a depot on the Underground Railroad. A stop where, if you need to get supplies to keep going further north, they will protect you, they will hide you, they will do whatever they can, even at the risk of their own lives. That was part of the mantra of their group, that we will protect fugitive slaves even at the risk of our own lives.

They had this reputation that if you got to their home you could be protected, and everyone in that community would work to protect you. So, four enslaved men escape Maryland and they wind up going to Christiana. They go straight to the Parker’s home, where William and Harriet Parker basically say, “Come on in. We’ll hide you in the attic and we’ll help you get further north.” Well, because of the Parker’s reputation, it’s a matter of hours before the enslaver, Edward Gorsuch, his son, his nephew, a U.S. Marshal — and I think maybe one other person — showed up at the Parker’s home, banged on the door and said, “We know you’ve got our enslaved property and we want them back.” I’m paraphrasing a lot of this, but that’s essentially what happened. Then William Parker comes to the door and he’s like, “Over my dead body. That’s not happening. You’re not getting these men back.”

Then Eliza goes up to the roof, and basically is like, “Babe, you want me to sound the alarm? I will sound the alarm.” She starts blowing this horn for the Lancaster Black Self Protection Society, the horn that would alert everybody that danger is here, come to our house, meet us, help us out. The men who are outside start shooting at the window. Thankfully, they live in a stone house. She’s hiding under the window but still blowing the horn while hiding under the window. Within minutes, 80 men and women, white and Black, show up with rifles, pistols, pitchforks, and farm equipment, ready to protect these four enslaved men.

It’s crazy because Eliza’s brother-in-law is panicking. He’s like, “No, just give them up. Give them up.” And Eliza, she picks up a corn cutter — which is like a machete — and she basically says, “I will chop off the head of the first member of our group that tries to give these people up. This machete is not just for enslavers. This machete is for snitches. Snitches get stitches!” That’s what she said. So long story short, all of a sudden shots are fired. We don’t know who fired the first shot. An altercation ensues. Edward Gorsuch is laying on the ground, dying. His son got shot and took off. The nephew and the U.S. Marshal, they see they’re outnumbered, so they take off. It’s wild.

What’s crazy is that William Parker writes about this in his narrative. He says Edward Gorsuch lay on the ground dying, and then he says the women put an end to him. The women put an end to him. As I’m in the archive reading these things, I’m like, “What, did they slit his throat? Did they snuff him out? What did they do? I don’t know.” All I know is that this tells me a lot of things: that women were very much engaged in violent resistance; that women were not timid and unafraid — they were not the damsel in distress — they were the ones that were sounding the alarm, picking up corn cutters, and ready to take out the master as he lay on the ground dying. For me, the story is like the pinnacle of protection. They don’t know these four enslaved men, but they help them anyway.

And they manage to escape. They get all the way to Rochester, New York. They stay in Frederick Douglass’s home. Frederick Douglass writes about this in his narrative. He’s like, ”Yeah, I saw these men. I saw William Parker, and I helped them get on a boat to Canada. As they’re getting on a boat, William Parker is like, “Hey, Freddie Doug, I got a gift for you. I want to give you a token, a memento of the battle of Christiana,” and he gives him the pistol that fell out of Edward Gorsuch’s hand. To me, that whole thing, I mean the abolitionists were gangster. They were gangster, and they knew what they were up against was life or death. And I just love that story. I’m sorry that took too long. But, if you want to read the book, there’s more to it. There’s more that happens. There’s plot twists.

Hagopian: Everyone’s got to read the book and get that story. I told you I was down in Mississippi last June and I got to interview someone that knew my enslaved great, great grandmother. And she talked about surviving during Jim Crow. They burnt down the daycare center in their town, trying to drive all the Black people out of the town. They armed themselves, resisted, fought back, and were able to reopen the daycare center in a tent. It didn’t end. That story just made me think of how much they refused.

Kaler-Jones: Yes, this is so powerful! I don’t know about everybody else, but I was on the edge of my seat for that story. As we’re talking about force, as we’re talking about this refusal through resistance and protection of community of self, in your book you state, “Black people have always used force not to oppress, but to protect, defend, and liberate themselves.” So, how do you see this distinction between using force for liberation versus oppression? How does that play out in both historical and contemporary resistance movements?

Jackson: Another good question. Force and the way I define it is really about arresting violence. It’s not about committing acts of violence; it is about compelling forcefully to get someone to stop. I think that’s really an important distinction we’re talking about — really it’s armed self-defense, protective self-defense. We don’t interrogate white violence enough; so much of the gaze is put on Black response. Are they going to be violent? Are they terrifying? Do they have guns? Do they have weapons? And we never talk about the fact that white supremacy is violent. It is violent. It is so violent that we have story upon story upon story of Black people trying to resist it.

I push on this a lot because I feel like when we talk about violence, it’s really not a two-way street. It just isn’t. We don’t have stories in which four little white girls are killed while worshiping in their church. We don’t have stories in which white men are assassinated in their driveway in front of their family like Medgar Evers. We don’t have stories where 14 white boys are killed while visiting the North, in a Black community like Emmett Till was in reverse. We don’t have these stories of Black people going to white churches and being welcomed by white churches, and then proceeding to shoot up the entire church like Dylann Roof did in South Carolina. There is no Black corollary for that and I think that’s so important to harp on, because oftentimes we think about Black violence and we think that Black people want revenge for slavery, or they want revenge for Jim Crow. I say in the book, “No, revenge is a white imaginary project. White people are obsessed with revenge. Black people are not. Black people don’t want revenge, they want justice. And justice is much more costly than revenge.” It is much more costly. But most Black people just want to live their lives. Most Black people don’t want to be a hashtag or statistic.

So, the way that they’ve had to do that oftentimes is to take up force when nothing else will work. To me, it was important to talk about the ways that armed resistance was successful, because I think that a lot of times we think that Black people who use guns or take up guns are somehow bad faith actors. Nothing could really be further from the truth. There are stories after stories of Black people who really don’t shoot white people, but just have the gun, and the gun is enough to scare away the Klan or whoever is trying to terrorize them. Ida B. Wells talks about the importance of having a gun. Rosa Parks talks about her kitchen table being covered in guns during the Montgomery Bus Boycott. I learned about my grandmother, who was packing heat and carried a gun. These stories, I think, are stories in which Black people are asserting their own rights to protect themselves. So, it’s never about causing harm, it’s always about stopping harm.

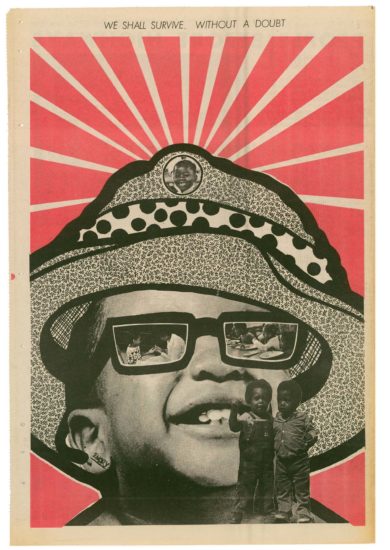

Even if you look at the Black Panther Party — I think this is really important — the Black Panther Party starts out using guns as a way to assert themselves and protect other Black people in their community from police brutality. They have this whole cop watch thing. But I also think that really the bedrock of the Black Panther Party was not force — it was protection. Within a year, they actually decided the guns were backfiring. No pun intended. They’re not really helpful. What is going to help us more is feeding our community, educating our community, making sure that our children have something to eat, and that our people are well cared for. I think the federal government, if they were honest with themselves, was more afraid of a well-fed, well-educated Black child than they were a Black man with a gun.

That is why the Black Panther Party got shut down, not because of guns, but because the breakfast program spread across the country, the literacy programs, the grocery programs, the public health programs that they had. They’re like, “Whoa, Whoa, Whoa! The government should actually be doing this.” It terrified people in the FBI. But for me, I saw what the Panther Party was doing as a form of not just force, but also an extension of protection. So it’s important to distinguish those two a little bit. I talk a lot about guns, I talk about Daisy Bates and the Little Rock 9, and how she used the gun. But again, she doesn’t kill anybody. She fires off some warning shots, and that’s enough to scare away the Klan, or whoever these white people are.

But, at the end of the day, it’s going to sound bad, but it is what it is. At the end of the day, a lot of white people are cowards, and when their own life is on the line they stop those shenanigans. When somebody armed shows up like, “Oh, you want to go toe-to-toe? You come to my house like you want to play these games?” Play stupid games, win stupid prizes. I feel like that is how a lot of Black people engaged. And when white people saw that — “Oh snap, these Black people are going to fight back” — a lot of that racial violence stopped. There are stories where riots in Black communities actually get quelled, actually stop, because there’s an armed Black presence in that community, and the white folks know it.

Hagopian: Oh. wow! Thank you for keeping it real, for teaching us all this history. This has been an amazing start to the conversation.

[breakout rooms]

Kaler-Jones: Welcome back, everyone! I hope you had rich discussions.

Hagopian: Let’s jump back into this conversation. I wanted to get back to Dr. Jackson and ask about your chapter called Flight. You write, “Flight is one of the most common actions in the history of Black resistance. It can mean quitting a job or a place. It can be short term or permanent.” I love this framing of how you talk about what flight is, and I was hoping you could talk about fight as resistance, especially in the way you reframe the Great Migration as a mass refusal to accept the terror of Jim Crow, and viewing that as a political act?

Jackson: Yeah, flight is probably one of the most widely used forms of resistance. I’ve definitely seen it in my own family. I’m a product of the Great Migration, my family was. They all hail from Louisiana and Mississippi, and they all migrated up to Detroit and Chicago during the automotive boom. I thought about flight in this current election, because people always — listen, if it goes sideways, we’re going to Canada, we’re going to Ghana. Where are we going? Black people are always thinking about where we’re off to. I even think about flight in terms of when the automotive industry in Detroit started to fade. A lot of my family members left Detroit and they went back to the south — they went to Houston, they went to Atlanta. So we see flight.

At the end of the American Revolution we see flight. During the Civil War Black people are leaving plantations. We see flight during the Black Panther Party. A lot of Black Panthers went to Tanzania or went to Algeria. So flight is common. What I think is problematic about flight, though, is that it’s probably the least effective of all of the remedies or the tools that I talk about. I say that because it’s so individualistic, meaning I can leave, but can we leave? I mean, when I think about We Refuse, I think about the collective. When you think about the fact that anti-Blackness is global, that there’s really no place in the world where you can go where there’s not either white supremacy or anti-Blackness, it means that you really have to do the work right where you are.

Oftentimes, while talking about flight I talk about truancy, because truancy is maybe leaving for a short period of time and then coming back. It’s what a lot of enslaved people did. Maybe they couldn’t leave Georgia and get to Boston, but they could go out to the woods or to the swamp for two weeks, and they could rob the slave holder of their labor, of their bodies, for that short amount of time. And it would give them respite. They would leave and maybe go to another plantation, maybe visit a loved one, like Frederick Douglass’s mother did. She would walk 12 miles just to sleep a few hours with her son when Frederick Douglass was a child and then walk 12 miles back to her plantation before the sun came up.

I tell this story not in the book, but in another book, in which there’s a woman that ran away from her plantation. When she got captured she was sent back to the plantation, and as a form of punishment they put her inside of a wheelbarrow that was hammered with nails and they rolled her in it. I was like, “Oh, my gosh!” She says when she gets out of the wheelbarrow, “It wasn’t until two weeks later that I ran again. I could not stay there.” It’s a great title of an article written by Stephanie Camp called I Could Not Stay There about how, even when you know that the consequences are dire or death, Black people refuse to stay in their subjugation.

So, flight is one of the ways that Black people manifest that. But flight is also limited. Because outside of the United States there’s not one single country in the world that can come to the United States without a visa. Not one single Black country, like you could do if you were in Germany or Italy. Say I want to go on holiday, I want to go to New York City, let me just book a ticket and go. You can’t do that if you live in Ghana. You can’t do that if you live in Jamaica. We have really racist policies that limit Black mobility all over the world. So it’s worth talking about. That’s why I put it in the chapter. But I’m clear about its limitations, too.

Kaler-Jones: Thank you so much for that. We appreciate hearing about how Black folks have used flight as a form of resistance and refusal. For the next question we want to talk about the chapter on Joy. I saw Joy come up in the chat. Jesse and I were talking about this. We’re so excited. I’m a dance teacher, Jesse’s a musician, so reading this chapter, we were like, “Oh, yes, we love to hear it.” You write that, “Joy is its own form of resistance,” and that “Joy is pride that can be expressed with swaying hips, stomping feet, and jolts of back-arching dance moves.” So, in what ways are dancing, singing, and loving acts of defiance? And how can you teach about and create space for Black joy?

Jackson: Joy is a weapon. Y’all, joy is a weapon. It is how we fortify ourselves. It is how we protect ourselves. It is how we enact our humanity. I can’t think of a Black experience that does not include or strive for joy, even in the most difficult violence. You think about the institution of slavery, and yes, there were times when enslaved people laughed, when they danced, when they enjoyed a good meal. I’m not saying that to belittle slavery, to say that it wasn’t that bad. I’m showing that Black people always carved out spaces to assert their humanity, and joy is a part of that. So I talk about it a lot in the book.

I talk about how I cultivate joy with my children. There’s a quote by Ashley Simpo that says, “Some of us fight racism by teaching our Black children to know joy.” This matters, too, and joy can be so superficial. At the end of the book I close by talking about my daughter and how my daughter has the most infectious laugh. I don’t need to know what she’s laughing about, if I hear her laughing, I’m cracking up because I just love her laugh. And how she recorded herself singing. The singing was so terrible, she was way off key. She’s screaming out the note and we’re listening to this recording together and we are hollering with laughter. I thought about that and I was like, “Well, what does this moment have to do with white supremacy?” And I’m like, “Nothing. That’s the point. That’s the whole point.”

Whether it is dancing or sharing a good meal or coming up with a hilarious meme like we did for the Montgomery Brawl — the Montgomery Brawl was all about joy. Do you know what I mean? It was all about laughter and creating these moments of levity and pointing out the absurdity and the ridiculousness of racism. We see it in our protests when in 2020 people would be marching and then all of a sudden somebody would play RIP, Frankie Beverly from Maze, and you’re like, “Wait a second. It’s a party.” The next thing you know people are dancing. Imani Perry says this as well. That it’s not Black people making light or being superficial of their trauma, it’s a way of them insisting on their humanity. We dance, we laugh, we sing, we eat, we love to insist on our humanity. And that’s why joy is so important. You can’t just have anger, you need joy, too. And you can’t just have joy because there are reasons to be angry, and so we need a healthy balance of both.

Hagopian: Yes, we are equipped for the struggle now with all of that wisdom. We really appreciate you highlighting that. People have to read to the end to get the chapter on Joy, and I hope you all will.

Jackson: I could do a whole book on joy. Y’all watch out, I might do a whole book on joy.

Hagopian: Good idea! I know Cierra’s working on a book about dance and arts and all forms of artistic expression with pedagogy, and I’m excited about that project, too, Cierra.

Jackson: I love it. Can I just say one thing? I’m going to keep this quick. I think it’s so important as teachers and educators, something I started doing maybe a few years ago — especially because I teach a lot of courses on slavery, the Civil Rights Movement, and a lot of stuff that’s just doom and gloom and drama — I said I wasn’t going to teach a class anymore where we didn’t dedicate like a whole week to Joy. Whether that was how the enslaved created their own dance parties out in the woods, which they did; how Black people in the South created their own safe houses and places where they could go to share a good meal or eat; how Black people created knitting circles just for their own wellness and enjoyment. I think it’s so important to highlight music, theater, and sports. Whatever it is that brings people joy that you can use as a counterbalance, I think, is so important, because our students want to be empowered, too. They don’t want to feel like they’re taking a class that shows Blackness is a problem. They want to have pride. So, including that joy is about instilling pride in Black culture.

Hagopian: I love it! The right wing always says that what we’re doing is making victims, that we’re just teaching Black children to be victims, and it’s a foul lie because we’re teaching them how to be empowered, and the history of resistance. But we’re also teaching them that joy and how to be joyful in your Black skin. So this puts lie to everything the right wing is saying about what anti-racist pedagogy looks like. And I wanted to just finish up with a question about that.

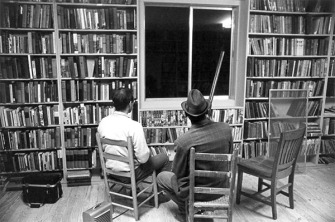

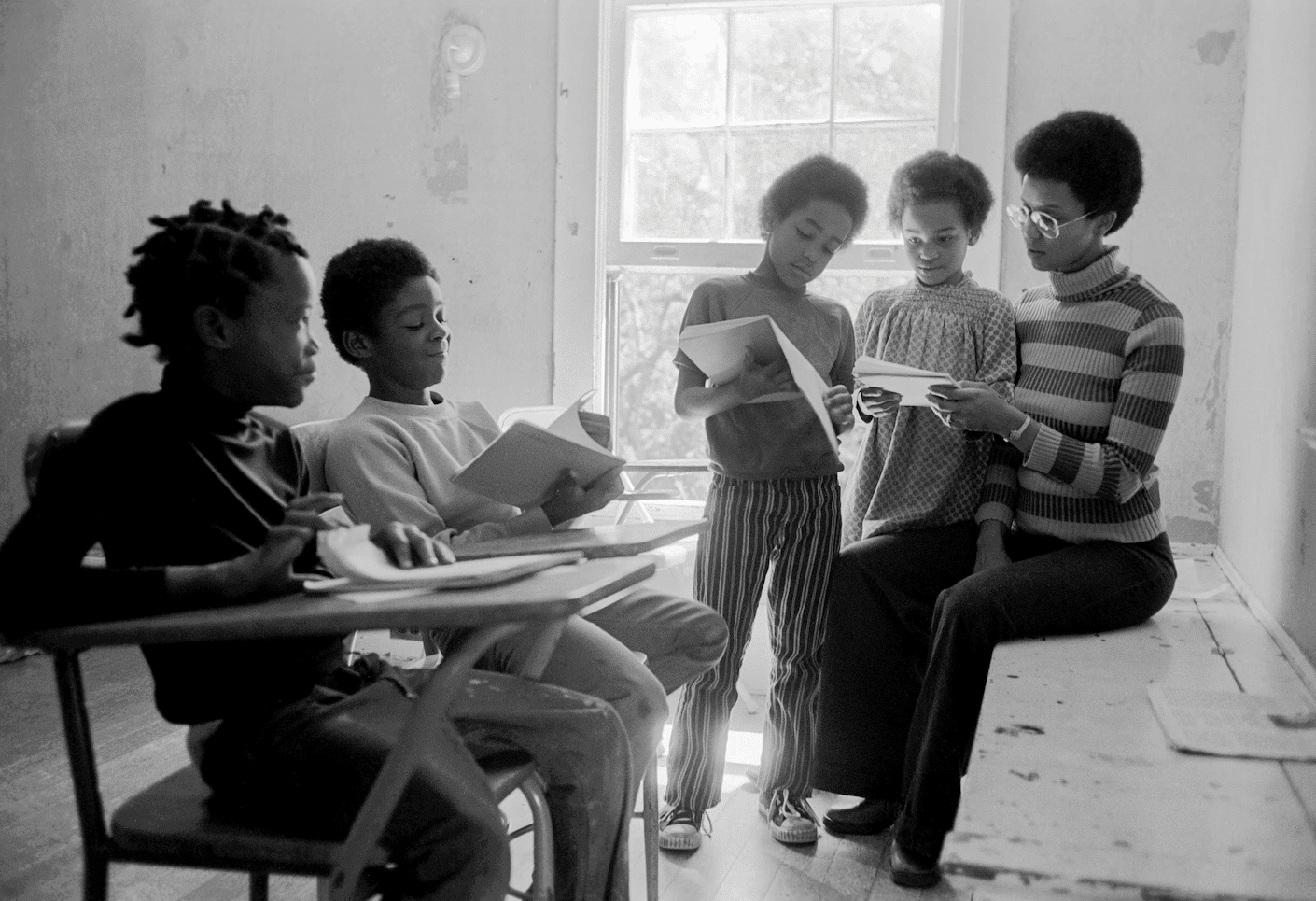

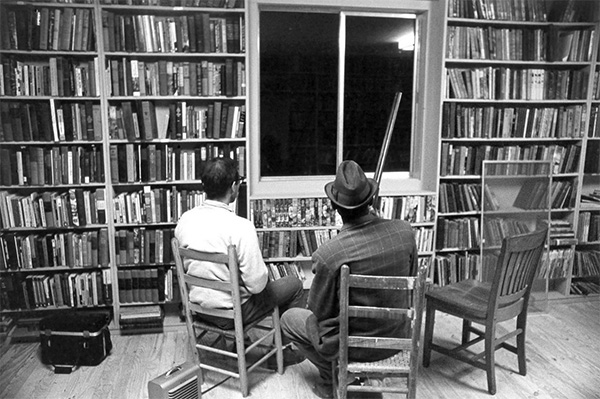

This attack that’s happening on anti-racist education. You write in the book, quote, “Educating Black children has always been a political act. From the moment literacy was banned for enslaved people, the work of getting Black children education could be met with danger and even deadly force by white supremacists who wanted a subjugated Black class. And this history is clearly repeating itself. It is particularly important that we study now in light of laws that are banning anti-racist education and the teaching of honest history.” So, what lessons from past struggles for Black education can we apply in this current moment to build fights to end these laws and to win Black studies and ethnic studies?

Jackson: I feel like it is an all hands on deck approach and we need everything that I talked about in the book. We need revolution, we need protection, we need force, we need flight, we need joy, we need spaces where we have our own classrooms, where we educate our children in ways that our public schools will not. There were a lot of Freedom Schools and Literary Schools during segregation and Jim Crow; we need spaces where we can retreat and leave to feel safe in and be away from the white gaze. That’s important, too. We also need grassroots workers and activists and people that are going to be like, “Oh, hell, no!” and march and protest and demand policy changes and say, “No, this does not work for our school district. This does not work for our community.” We need collective refusal. I think that’s so important.

I am not resigned at this moment. I’m not just like, “Oh, well, they made another law. I just can’t do anything about it.” We make the laws; we are the law. I think being able to push back on that and say “No.” To me, that’s going to take on a lot of different variations. I tell people this book is not a how-to guide. It’s not. We’re not going to solve racism in three parts; that’s not what this is. But it is a way to encourage more conversation, to think about the myriad of ways — not just the five that I offer — but the multiple ways we can engage and combat white supremacy at an individual level, at a collective level — in our homes, in our schools, in our spiritual places of worship, at the local level, at the national level, [and] at the global level. I want people to be doing this work, engaged in this work. It doesn’t mean that you have to put your body on the line, but it does mean that you have to be willing to engage, willing to make sacrifices, and willing to ask the hard questions and different questions. It’s necessary work.

Hagopian: Well, you’ve really filled my heart tonight. I know Cierra, too.

Jackson: Thank you. Same here. Likewise, we need each other. It’s a good solidarity action right now.

Hagopian: No doubt. Thank you so much for taking the time this evening. What an incredible conversation! I’m really excited about this growing community that we’re building here of teachers and educators across the country who are doing this refusal, who are building this collective resistance. So thank you all for being a part of this.

While this transcript was edited, there may be minor errors or typos — if you notice something you believe to be incorrect, please contact us at zep@zinnedproject.org.

Audio

Listen to the recording of the session on these additional platforms.

Resources

Here are many of the lessons, books, and other resources recommended by the presenters and participants:

Lessons

|

Poetry of Defiance: How the Enslaved Resisted by Adam Sanchez ‘If There Is No Struggle…’: Teaching a People’s History of the Abolition Movement by Bill Bigelow Teaching With Seizing Freedom by Ursula Wolfe-Rocca Reconstructing the South: What Really Happened by Mimi Eisen and Ursula Wolfe-Rocca When the Impossible Suddenly Became Possible: A Reconstruction Mixer by Adam Sanchez and Nqobile Mthethwa What We Don’t Learn About the Black Panther Party — but Should by Adam Sanchez and Jesse Hagopian The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks teaching guide Why I Teach Look for Me in the Whirlwind by T.J. Whitaker (Rethinking Schools) |

Books

| In addition to We Refuse: A Forceful History of Black Resistance, the following books were referenced.

Force & Freedom: Black Abolitionists and the Politics of Violence by Kellie Carter Jackson 1919, The Year of Racial Violence: How African Americans Fought Back by David F. Krugler Hands on the Freedom Plow: Personal Accounts by Women in SNCC edited by Faith S. Holsaert, Martha Prescod Norman Noonan, Judy Richardson, Betty Garman Robinson, Jean Smith Young, and Dorothy M. Zellner Look for Me in the Whirlwind: From the Panther 21 to 21st-Century Revolutions edited by déqui kioni-sadiki and Matt Meyer No More! Stories and Songs of Slave Resistance, a picture book written by Doreen Rappaport and illustrated by Shane W. Evans They Left Great Marks on Me: African American Testimonies of Racial Violence from Emancipation to World War I by Kidada Williams |

Articles

|

Guns and the Southern Freedom Struggle: What’s Missing When We Teach About Nonviolence by Charles E. Cobb Jr. (from the Zinn Education Project’s If We Knew Our History series) Five Ways Textbooks Lie About Reconstruction by Mimi Eisen (an addendum to the Zinn Education Project report, Erasing the Black Freedom Struggle) Remembering Red Summer — Which Textbooks Seem Eager to Forget by Ursula Wolfe-Rocca (from the Zinn Education Project’s If We Knew Our History series) |

Podcast and Film

|

Seizing Freedom, a podcast by Kidada E. Williams, tells stories of Black Americans’ quest for liberation, progress, and joy Slave Catchers, Slave Resisters, a film produced by Judy Richardson and Northern Light Productions for the History Channel, depicts many rebellions by enslaved people and other forms of resistance |

This Day In History

The dates below come from our This Day in People’s History collection, which contains hundreds of entries all searchable by date, state, theme, and keywords.

Participant Reflections

With more than 200 attendees, the conversation and chat was lively, engaging, and full of history, teaching ideas, and more. Polls showed participants included 39% K–12 teachers, 18% teacher educators, 9% historians, and many more.

Here are more comments that participants shared in their end-of-session evaluation:

What was the most important thing (story, idea) you learned today?

I appreciate the centering of Black women’s stories in the narrative of resistance.

I attended with my students. They appreciated the part about the Haitian revolution and also the Black Panther Party. They also enjoyed learning about the Lancaster Self-Protection Society and the role that Black women had in that organization.

The idea that educating and feeding a Black child is more powerful and threatening than a Black man with a gun.

I really valued Dr. Jackson’s teaching that we don’t interrogate violence enough, particularly white violence. Rather, we are obsessed with defensive responses. I want to think about that in my daily life as it pertains to young people and the ways we resist university structures and other arms of the empire.

I loved learning about Eliza sounding the alarm for the Lancaster Black Self-Protection Society. Thanks to her unflinching commitment and refusal, enslaved men were able to escape.

Joy as resistance; a well-fed Black child who is educated; honest history — all of these are dire threats to white supremacy.

Resistance comes in many forms.

The American Revolution was not a revolution — it only benefitted one group, not all, and “liberation should liberate other people.”

My mind will forever be blown about two things: South America has Haiti and its Black revolutionary leadership to thank for its freedom, and America was conceived in 1776 but born through the Civil War.

The influence of the Haitian Revolution throughout the Caribbean and South America.

Revolutions are just the beginning and not the end point! It is an ongoing fight for liberation for all. We must be a part of the collective resistance.

Community is the key to everything.

Black resistance was evident in all facets of the making of America.

I really liked the part of the conversation where they were talking about modern day refusal. I liked how Kellie Carter Jackson framed refusal in many different lights. Flight is a form of refusal, dancing and singing are a form of refusal, and expressing your culture.

Healing thyself is revolutionary.

What will you do with what you learned?

I want to infuse my syllabi on social movements with a unit on joy. I also can see linking the forms of refusal discussed in We Refuse to other displays of refusal against white supremacy, like Native American resistance to oil pipelines.

I can’t wait to share this book with my students. I teach all girls and they love stories of female resistance to oppression!

I teach rhetoric(s) of resistance and will happily add this story and text to my course list. I am an organizer and will share this text with student organizers during our groundings sessions.

This presentation provided me with several fresh perspectives for museum education programs on the American Revolution, enslavement, abolition, and Reconstruction.

I am excited to use the lens of refusal in my work with artist teachers who will be using the arts and creative strategies to connect history to contemporary movements, and for engaging students in imagining forms of creative resistance and activism in their own lives — and through art!

I’m a student, not a teacher, but I will take into account the action of refusal and the diversity of methods of resistance in my analysis and understanding of history and freedom struggles.

The concept of collective refusal as an act of Black liberatory resistance is a theme I will continue to explore.

I’m going to host an informal educational group to discuss this recording once it is available.

I think this has given me the tools to engage students in discussion on the role of guns in self-defense in a way that isn’t triggering or that doesn’t compound any trauma that exists around the issue of gun violence. Contextualizing the Black community’s relationship with guns within our history of refusal feels safe for all my students, even empowering.

I will infuse teachings of Black joy within my units throughout the year, especially when we talk about the institution of slavery.

I hope to use stories from the book to inspire discussion. I intend to introduce each of my classes with a positive story to highlight the joy that fed the resilience and helped to build perseverance.

How was the format for the class?

I thought it was one of the best virtual PDs I have been to in a while. Many are too long and don’t respect attendees’ time. This felt like a perfect mix of facilitation and space for participants to discuss. I felt positive about all segments and look forward to attending more!

It was great. I often don’t like breakout groups but I did tonight. The size of our group was perfect, the questions were good conversation starters (and did not overwhelm us). We actually had an opportunity to hear from everyone, maybe twice.

Great format! I loved the time and the pace of the class.

The format worked very well! It’s rare to place the breakout groups in the middle of the session, but I think it was effective to reflect on what we’d learned previously, share thoughts, and bring them back with us to keep learning.

I felt that almost everything about the meeting was amazing. One of my best Zoom meetings yet. I only wish that it were longer.

Presenters

Kellie Carter Jackson is the Michael and Denise ‘68 associate professor of Africana studies and the chair of the Africana Studies Department at Wellesley College. She is the author We Refuse: A Forceful History of Black Resistance and Force & Freedom: Black Abolitionists and the Politics of Violence. She has also given a TEDx talk on “Why Black Abolitionists Matter.” Her next book project is entitled, Losing Laroche: The Story of the Only Black Passenger on the Titanic, which traces the story of Joseph Laroche and examines the possibilities and limitations of Black travel in the Titanic moment.

Cierra Kaler-Jones is the executive director of Rethinking Schools. Cierra is also on the leadership team of the Zinn Education Project, which Rethinking Schools coordinates with Teaching for Change, and has hosted many of our Teach the Black Freedom Struggle classes. Cierra is a teacher, a dancer, a writer, and a researcher. She previously served as director of storytelling at the Communities for Just Schools Fund.

Jesse Hagopian teaches Ethnic Studies and is the co-adviser to the Black Student Union at Garfield High School in Seattle. He is an editor for Rethinking Schools, the co-editor of Teaching for Black Lives, editor of More Than a Score: The New Uprising Against High-Stakes Testing, author of Teach Truth: The Struggle for Antiracist Education, and serves on the leadership team of the Zinn Education Project.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn