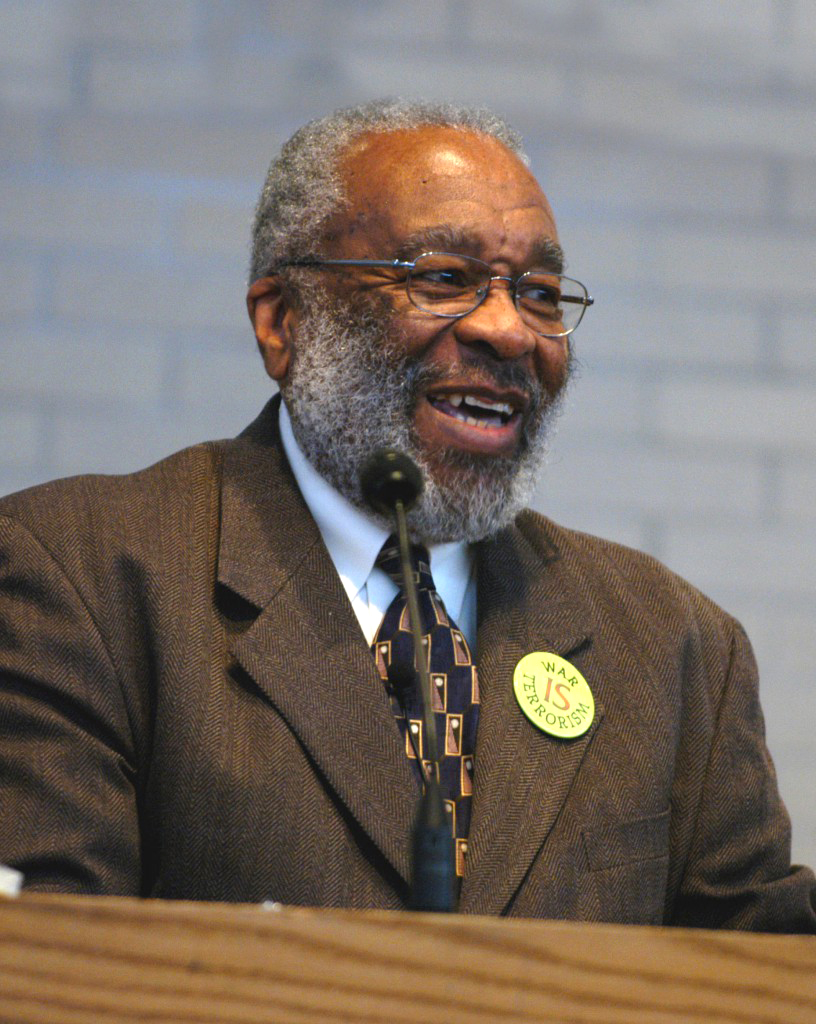

Esteemed historian Vincent Harding shared memories of Howard Zinn at the SNCC 50th Anniversary Conference in Raleigh, North Carolina in April 2010. His tribute was offered during a part of the program entitled “In Remembrance,” moderated by Charles Sherrod at the Shaw University Chapel. The session included a series of speakers who shared stories about SNCC veterans who have passed.

Howard, originally scheduled to speak at the conference, died in January of that year. While his name was added to the roster of veterans who had passed, no one had been assigned to speak about him. After an awkward moment of silence, audience member Harding walked up to the podium and spoke. He began by expressing his disappointment that a volunteer needed to be recruited. As is evident from the video and transcript below, the audience was lucky that Harding “wandered in” as he said, since he spoke with such deep love and respect for his colleague of many years.

Recording

Transcript

Charles Sherrod: Now this one is sort of tricky, because I don’t know who’s supposed to speak for Howard Zinn. Can I get a volunteer, somebody who knows a little bit about Howard Zinn to speak his name?

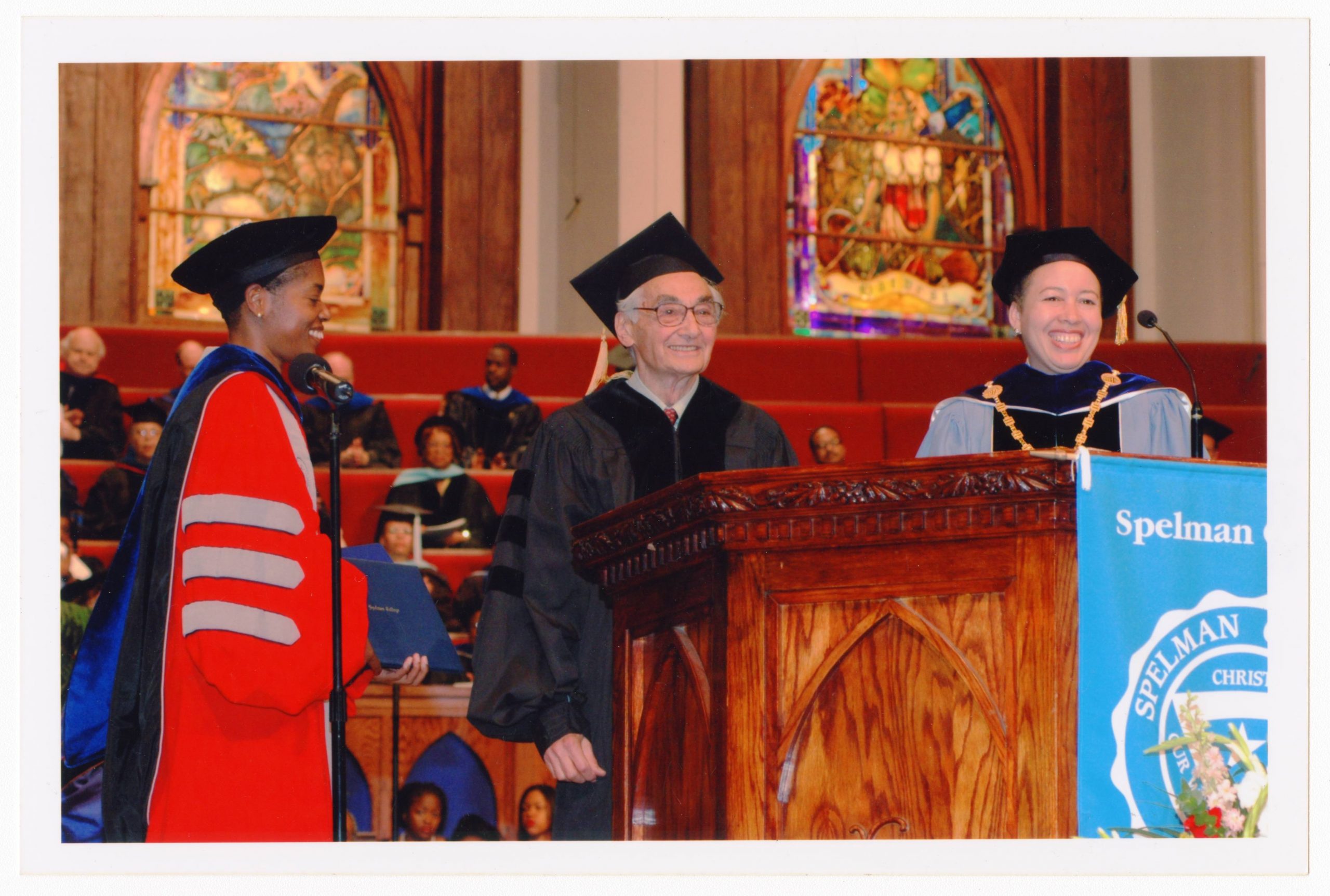

Vincent Harding: I must begin by expressing great sadness for the fact that Howard Zinn needed a spokesperson to be recruited from his memorial audience. Let me discipline my own feelings at this point and go on to tell you a very brief story about Howard and me and Spelman College.

Some of you know that Howard Zinn was part of that fascinating, in many ways courageous and often very helpful, gathering of white scholars who, even before 1960, had chosen for a variety of reasons to bring their lives down to the South. Most of them originated in the North, some originated overseas, but who all wanted to come to offer whatever their gifts were. And in some cases, one of their major gifts was simply the possession of a PhD, which would help the Black schools in the accreditation battles that they fought for a long, long time to be recognized as schools that needed to be accredited.

Howard came to Spelman in that grouping sometime before I met him. I’m fairly certain it was in the midst of the 1950s. Howard was a real believer in participatory democracy and none of the Black schools at that point encouraged participatory democracy. Indeed, they were very frightened, troubled, and unsure about what to do with something like participatory democracy.

As a result, Howard got into a good deal of trouble. At Spelman, he not only encouraged his students to participate in the rising movement among students at Black schools and universities, but he encouraged his students to be consistent, and to challenge injustice wherever they found it.

And therefore some of his students, including Alice Walker, wanted to challenge the injustice that they found on their own campus. And as they raised their voices about such things, while at the same time being involved in the struggles off campus, the administration at Spelman made it very clear that if the students continued that they would be in trouble. They would lose scholarships. They would be kicked out.

And Howard Zinn was considered to be an agitator, an instigator, and generally bad for the status quo. And through a long sequence of actions that I will not try to go into now, Howard was essentially kicked out of Spelman College.

I was living in Atlanta, involved in the movement at that time. I had no connection with Spelman at that time, but knew Howard, knew Staughton Lynd, knew many of the beautiful students who were on that campus and the Morehouse campus and the Morris Brown campus and the Clark campus and the ITC [Interdenominational Theological Center] campus. My late wife Rosemarie and I were very close to those students. And I was asked by some friends to join them in a delegation to president Albert Manley of Spelman College to ask him if he would not rethink the decision that he had made about Howard Zinn. Manley would not, and the deed was done.

Several years after, as I finished my own long, long delayed work on my doctorate at the University of Chicago — almost at the moment that my dissertation was accepted and my assurance of participating in the commencement for the June 1955 graduation at the university was assured, in ways that I still don’t know the origins of now — somehow president Manley discovered my number and called me and asked me if I would come to Spelman College to be the chair of the history department. The position that Howard Zinn had been pushed out of.

As I talked it over with my wife Rosemarie, we came to the decision that I wanted and needed to be with those students, but that I would go only as a faculty person and not take that role that Howard had had as chairperson of the department (of course, in those days, [there was] no such thing as chairperson). I was about to tell Dr. Manley that when we decided that it was absolutely important for me to contact my friend Howard and see what he thought about this situation.

I called him — and this was Howard Zinn, this was his spirit. Howard said,

Vincent, you must go there. Those students in the AU Center, and at Spelman particularly, need as many Black male presences as they can get on those campuses. But do not go simply as a faculty person. If you go on that campus, you must take some power with you, and the faculty role is not powerful enough. He said my chairperson role wasn’t powerful enough, but maybe you in the chair role would have a different kind of result than I did. But whatever the case is, he said, Vincent, go, that’s where you should be.

There was never an ounce of statement of resentment leading him to say, “No, don’t have anything to do with them.” The Howard Zinn who loved his students was sending me to his students. And I never forgot that conversation, never will forget that Howard Zinn. We had many, many times of connection, of working together, that I will also never forget.

And so even though I am sad that there was no one to speak, but someone wandering in as it were, I am glad that I’m here to speak because I love and respect and have such tremendous appreciation for the man, for the scholar, for the teacher, and for the outspoken caller for a more democratic society, that I’m honored to be asked to be a voice for Howard Zinn on this occasion. Thank you.

The video clip is provided courtesy of the SNCC Legacy Project.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn