On February 10, historian Justene Hill Edwards and Rethinking Schools editor Jesse Hagopian discussed Edwards’ book, Savings and Trust: The Rise and Betrayal of the Freedman’s Bank, a comprehensive account of the Freedman’s Bank and its depositors.

This class was part of the Zinn Education Project’s Teach the Black Freedom Struggle online people’s history series. Register here for upcoming classes.

In the excerpt below, Edwards explains the promising beginnings of the Freedman’s Savings Bank for formerly enslaved people, their incredible economic power in the early years of Reconstruction, and the “chipping away at the bank’s benevolent foundations” that soon followed. In a profound betrayal of trust, white board members and politicians turned it from a savings bank for African Americans into an investment bank to serve white business partners, friends, and family of its white trustees.

Through this shift to investments and the economic depression known as the Panic of 1873, white financiers’ mismanagement and fraud caused the collapse of the Freedman’s Savings Bank in 1874. They loaned and lost millions of dollars of freedpeoples’ deposited savings, devastating generations of African Americans and opening up an enormous racial wealth gap that endures still today.

The real story of the Freedman’s Bank — not failure, but sabotage!

I did not know that the Freedman’s Bank even existed. It’s good to learn about things that have been historically ignored in our educational system.

How the fall of the Freedman’s Bank was one more hit to the generational wealth of Black people in this country.

The amount of money stolen from Black Americans through white lenders and investors looting the bank. I didn’t know that the bank existed, really, and to learn that so much was stolen from these families is heartbreaking.

African Americans contributed $57 billion to the Freedman’s Bank, which was corrupted by white capitalists and their business partners, and over 61,000 Black families were robbed of their life savings and generational wealth. Reparations are overdue and this is why they keep this history hidden.

Everything I heard today was all new and enlightening. The shrewd method used by whites to entice newly freed Black people to put their hard earned money in their bank only to turn around and steal it from them, and not to give it back when the bank went broke, is disheartening (just like all the struggles Black people went through and continue to go through with systemic racism).

The historical and systemic way that whites have exploited African Americans is deeper than I could have ever imagined. We need to be teaching authentic history! Our students and teachers deserve nothing less!

The defrauding was normalized by having Congress investigate and then “find” that African Americans were not capable of engaging in citizenship, personhood, practices of planning for the financial security and future of their families. This narrative that Blacks are incapable of taking care of themselves is a leitmotif to all white supremacist strategies and practices to annihilate Black humanity and community.

Event Recording

Transcript

Click below for the full transcript with resources mentioned in the discussion.

Transcript

Jesse Hagopian (he/him): Thank you all for joining us. On behalf of the Zinn Education Project, we would like to welcome everybody to our class this evening with Justine Hill Edwards. My name is Jesse Hagopian and I work with the Zinn Education Project, I’m an editor with Rethinking Schools, and I’m delighted to be with you all for this urgent conversation. . . .

I am so thrilled to get to welcome historian Justine Hill Edwards. She is an associate professor of history at the University of Virginia, and she is the author of the book we will be discussing called Savings and Trust: The Rise and Betrayal of the Freedman’s Bank. I can’t recommend this book highly enough. This is a must read to understand not only Reconstruction, but our own era today. And she’s also the author of Unfree Markets: The Slaves’ Economy and the Rise of Capitalism in South Carolina. Welcome, Justine, thanks so much for joining us.

Justene Hill Edwards: Thank you for having me. I’m so happy to be here this evening.

Hagopian: Alright, alright. I’m excited to dig into this brilliant work. I wanted to start with the Bank and ask you what was the Freedman’s Bank and why was it such an important institution in the era of Reconstruction? I want to get at what were the hopes of so many formerly enslaved, now freed, Black folks who put their money in this bank, and if you could tell us about some of the people who first deposited their funds there.

Edwards: Sure. Well, again, thank you all for being here. Thank you for the team that invited me to come in and speak with you this evening. So, the Freedman’s Bank was founded and established in 1865. March 3, 1865, was actually when Lincoln signed the Freedman’s Bank Act, which created the bank — the Freedman’s Savings and Trust Company. It was established to help the formerly enslaved men, women, and children of the U.S. make the transition from slavery to freedom economically by helping them save money.

But, it is important to note that the Freedman’s Bank was really not the first instantiation of this idea of a savings bank for African Americans. Actually, in 1864, the Union Army created three military savings banks — one in New Orleans, one in Norfolk, Virginia, and one in Beaufort, South Carolina. I saw in the chat that someone is from Beaufort, and knew about the Beaufort branch. So these three military savings banks, again established in the summer of 1865, were created to serve one goal primarily, and that was because in the spring of that year the federal government and the Department of War actually created a law that allowed for Black soldiers to earn equal pay to their white counterparts. So they were earning money on par with white soldiers, and they needed a safe place to store their money. They were earning money that they wanted to essentially send to their families. So three Union generals created these three military savings banks in these three locations to help Black soldiers save money.

And these banks were wildly successful in the first six months, such that by the end of 1864, there was about $50,000 of Black soldiers’ pay deposited in these bank accounts. So these military savings banks kind of served as a test case, and proved that African Americans were interested in savings banking and would be reliable customers if a savings bank were created for them and their purposes.

Hagopian: This is fascinating history. That is just astounding, and I would guess most of us on this call never learned about it. I told you just before we went live that my dad just discovered an obituary for my great, great grandma, who was enslaved in Mississippi, and this just makes me want to look up and find out if she had deposits in the bank. There are so many questions I have now, after reading this book and learning about it, but I wanted to ask you more about the founding of this bank.

You write about how an abolitionist John Alvord became a champion for the Freedman’s Bank, and he highlighted the potential and really the optimism surrounding this bank. But you also point out that his leadership was marred by an inexperience in overseeing large financial institutions, but then also his decision not to include any Black leadership in the management of the bank. So, how did this absence of Black leadership shape the bank’s trajectory and ultimately lead to its exploitation? Maybe you could talk about that in terms of the founding of the bank.

Edwards: Sure. John Alvord was a white congregationalist minister, and at the outbreak of the war he lived in New Jersey. I think he had benevolent means. I think he wanted, at the beginning, to actually help African Americans. Going back to 1864, he was working as an attache with the Union Army and he took that opportunity to follow famed Union General William T. Sherman on his march to the sea. During this campaign he took that opportunity to meet with and speak with recently emancipated African Americans. and he asked them about their experiences in slavery, what they wanted to enjoy and experience in this new period of freedom, and, overwhelmingly, they said 1) they wanted to join with their families and reunite with their families, but 2) they also wanted the opportunity to buy land. Purchasing land and being property owners were really important goals for African Americans, especially freed people.

So in 1865, [Alvord] gathered a group of white abolitionists, ministers, philanthropists, bankers. In January of that year, he created what would be the Freedman’s Savings and Trust Company. At this point the bank’s founder, John Alvord, and the bank’s growing board of trustees — about 50 white men — were doing this and engaging and supporting this bank as a philanthropic measure. They weren’t really thinking about the Freedman’s Bank, as, I think, a serious financial institution. They were doing so as an act of philanthropy. And so John Alvord, again, he was not a banker. He did not really have much knowledge of the intricacies of finance and banking, especially at this time, when the landscape of banking was changing. In 1863, we had the creation of the office of the Comptroller of the Currency, and the Comptroller was supposed to be responsible for regulating national banks and bringing the thousands of state banks under the National Bank umbrella, creating a uniform currency — the dollar. Alvord would have known all of this had he had experience with banking. But he didn’t. And so he taps the men in his network that he knows, and they are all white men. It takes two years, in particular, for the first Black men to join the Board of Trustees. But, interestingly, in May of 1866, the trustees tap Henry Highland Garnett to be the bank’s first Black trustee. Now, interestingly, there is no information about whether he formally accepted or declined the invitation, but he subsequently did not join the board. Again, it took two years, until 1867, when the first three Black trustees joined the bank. And that happens during this moment of transition in the bank’s history when the bank’s main office is moving from New York to Washington, D.C. And that’s where those three first Black trustees come in.

Hagopian: Right on. Thank you for walking us through that founding and some of the potential consequences of the decisions they made. You also write about how the bank was moved around, and you say that relocating the Freedman’s Bank from New York City to Washington, D.C. under the influence of white financiers like Henry D. Cooke really opened it up to political and financial exploitation. So how did this change — the impact of the bank’s mission to serve Black Americans — and what role did it play in redirecting the bank’s resources away from the community that it was supposed to empower in the first place?

Edwards: Sure. Well, the bank first operates at a small level. Again, the major main office is in New York, close to the heart of financial power, which at this time was in New York and Philadelphia. And John Alvord comes up with this plan to relocate the bank’s main office. He wants to be closer to the heart of political power, and so with that he invites a group of white men led by a famed (or infamous now) banker named Henry Cooke. Now, Henry Cooke was an important figure in this period. He was a close personal friend of Lincoln. He was a close personal friend of Salmon P. Chase, who during the war was the Treasury Secretary, and at this moment in time, in the 1860s, he is the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court. He and his brother established Jay Cooke & Company, and Jay Cooke & Company was the nation’s first investment bank. They had made millions of dollars during the war, selling U.S. bonds both domestically and abroad. It was basically their fundraising efforts that helped the Union, at least financially, win against the Confederacy.

So he was extremely tapped into a network of bankers, most certainly a network of politicians, and when he was invited to join the Board in the spring of 1867, it marked this shift, not only a shift from New York to D.C., but a chipping away at the bank’s benevolent foundations. The bank is established to serve the formerly enslaved, to be a depository, a savings institution for them; but once this transition happens, once Henry D. Cooke joins the board and he brings two other men with him (one’s name is William Huntington, and the other’s name is D. L. Eaton) who would serve as the bank’s actuaries, the person responsible for evaluating risk, it dramatically marks a turn away from the bank’s fundamental mission of serving African Americans.

Hagopian: Yeah, it really seems like that was a turning point. And, unfortunately, it didn’t go well with white supremacists in control in the end. But you argue that the bank’s white financiers drove the bank into the ground, and it’s often explained that Frederick Douglass drove it into the ground because he was the final president. But you argue that it was actually the bank’s white financiers that drove it into the ground and that, instead of master narratives that we get so often, like it was Black depositors’ faults, or it was Frederick Douglass’s negligence. So what specific financial decisions or manipulations really were most damaging by these white financiers, and how did they contribute to the bank’s downfall?

Edwards: Well, this is really the heart of the story. If you recall, I mentioned a man named D. L. Eaton, and on April 19, 1867, he took the bank’s first loan. Now that’s important for a few reasons. The bank, again, is a simple savings bank. It’s established to actually not make loans. It’s established only to accept the deposits of the formerly enslaved or any other depositors. And that’s how it operated for the first two years. On April 19, 1867, Eaton — who at this time was a businessman, he owned a construction company, and actually he was close friends with Oliver Howard, who founded Howard University. He was contracted from Howard to provide the bricks that went to build Howard. So, interestingly, there’s a connection there. But when D. L. Eaton takes that loan of $1,000 it fundamentally changes the bank’s mission. Interestingly, he takes the position of actuary two weeks later.

So it’s kind of built, in this idea of corruption, very early on in the bank’s history. And that continues such that by the time the bank starts to invest money in buying a new building for the bank’s main office. At the same time, Henry Cooke decides to lobby members of Congress to amend the bank’s fundamental charter, and changes the bank’s mission from being a savings bank to an investment bank to a commercial bank. And a commercial bank can make loans. This happened and was approved by Congress in May of 1870. In May of 1870 the Freedman’s Bank really stops serving African Americans in the way that it was originally supposed to, and it turns into a lending powerhouse such that over the next two to three years the bank loans out millions of dollars to the white business partners, friends, and even family of the bank’s white trustees. By the time that we get to 1873, about four million dollars had been lent out to white borrowers, mostly in and around Washington, D.C. We find out later that about 10 percent of that money was lent out to Black institutions, like Howard, and Black churches in and around the city. Even the Douglass Institute in Baltimore gets a small loan. But the vast majority of that loan volume goes to the white trustees, their business partners, and politicians in and around D.C.

Hagopian: This is just incredible history — people just out of slavery are now able to earn wages, they’re working hard, and there’s all this discussion about how to really be free. You have to learn how to save your money. You write about how dedicated Black communities were to that principle, and how many millions of dollars they saved, and then to see that all get loaned out to predominantly white financiers and their aims is just breathtaking.

Edwards: I think it’s worth saying, too, that by 1870, five years into the bank’s tenure, African Americans had put about $12.6 million into the bank. That’s about $292 million today. It’s a staggering amount. By the end of the bank’s tenure in 1874, that number was $57 million, and that’s about $1.5 billion today, the vast majority of which was deposited by recently emancipated African Americans. This gives you hopefully a sense of the economic power that African Americans were bringing with them into this period of freedom, and really dispelling this idea that has been, I think, really understudied in the scholarship on Reconstruction, the fact that African Americans were an economic group that had incredible economic power. They were thinking critically about wealth and wealth building, having themselves been capital and property. They were thinking critically about wanting to pass on generational wealth through owning property, and so they were bringing that enthusiasm, and really that knowledge, to their engagement with the Freedman’s Bank in very meaningful ways.

Hagopian: You can’t understand the current wealth gap or this history without understanding all that. This is incredible history. You can see why they’ve hidden it from us. You can see why it’s not taught, because it really unlocks the understanding of that period, and so much more.

I wanted to ask you more about Frederick Douglass. Now, you know Frederick Douglass accepted the presidency of the Freedman’s Bank hoping to restore confidence in it. But it seems he was really being used as a symbolic figurehead, while white financiers had already pretty much doomed the institution by the time he came onboard, if I’m reading it correctly. I wanted to add that Frederick Douglass is a hero of so many, myself included. An incredible story of escaping slavery and teaching himself to read and write and become one of the greatest abolitionists in U.S. history. So I wanted to dig more into what his role here was, and ask do you think he should have accepted that position? Is there anything he could have done differently that could have saved the bank? Or was he going to be manipulated and it was doomed from the start? Then, how did this experience shape his later views on Black economic independence?

Edwards: I think I give Douglass grace in this respect. I think he had been wanting to make a more public foray into political life. There were calls for him to move to the South and run for a Senate seat. He wasn’t quite ready for that, and so he wanted to think critically about how he could best, I think, use his profile in a way that would benefit other African Americans. So his position with the bank, in his mind, was a step in that direction. Again, Douglass was not a banker, but that doesn’t mean that he didn’t have financial knowledge. He was running a newspaper, a very prominent newspaper, in Rochester, New York. He was running the premier Black newspaper in Washington, D.C. When the bank had moved there he was himself a depositor. He was thinking economically, and so I think he wanted to make a step that would best benefit him. And I think he thought that accepting the invitation to join the Freedman’s Bank as its president would be the best next step.

But, unfortunately, he takes the position in March of 1874, and he looks at the bank’s records and realizes that the bank is underwater. Far more in loans had been given out than they actually had to cover the depositors demands. He realized that many of the loans were unsecured, and, according to Congress, each loan was supposed to be secured with real estate twice the value of the loan. Sometimes stocks were given as collateral, which was running afoul of Congress’s mandate. So he quickly realized that the bank is underwater, and again, this was after two examinations, finally, from the nation’s Controller essentially saying that the bank needs to ridership because they are at risk of being insolvent. But by the time that Douglass steps into this role the bank is insolvent. He tries to rally the troops, he tries to get African Americans to not make runs on their bank branches. But by this time there’s really nothing that he could do to make sure that the bank was run as it should have been. So he takes the position recognizing that perhaps the best that he can do is try to get depositors the money that they have in their accounts, and this is where he runs into a challenge. Congress mandates essentially that the bank close. On June 29, 1874, the trustees met. They go back and forth and decide to try to see if the bank is redeemable. Essentially, they recognize that no, it’s not. So, on July 2, 1874, the bank suspended operations, closed its branches, and Douglass was left as the president of the Freedman’s Bank when it failed and collapsed.

Hagopian: And how much money was lost for Black folks again?

Edwards: Between 1873 and 1874, there were several runs on the bank, especially after the panic of 1873, which happened in September of 1873. Interestingly enough, the catalyst for that in the U.S. is the failure of Jay Cooke & Company. The famed investment bank, Jay Cooke & Company, through Henry Cooke, had borrowed at least $500,000 from the bank and by the time the bank closed in July of 1874, African Americans had left about $2.9 million across 61,144 accounts. But pair that with the fact that there were $3.5 million outstanding in loans, and the fact that there was less than $50,000 in cash and $400 in bonds, the bank was severely over leveraged, and African Americans, at the time that the bank closed, would not get their money, and they would spend years getting their money in return.

Hagopian: Oh, wow! Incredible. And you talked about the panic of 1873, so I just wanted to follow up on that briefly before we go to breakout rooms. It seems to me that the Freedman’s Bank collapse was not just the result of mismanagement. It definitely was mismanaged, and all the ways you described how the bank ran afoul of its congressional mandates, but also it happened in the larger context of the cyclical crises that capitalism goes through. And this was one that happened in the panic of 1873. So, I was wondering if you could talk more about how the broader economic collapse exacerbated the Freedman’s Bank vulnerabilities, and what does this really reveal about the way capitalist financial crises disproportionately impact Black communities?

Edwards: Jesse, I love that question. Well, the panic of 1873 was one of the major economic depressions of the 19th century. Again, the catalyst was the collapse and the failure of Jay Cooke & Company. At this time Jay Cooke & Company was heavily invested in the transcontinental railroads, specifically the Northern Pacific Railroads, and they were responsible for selling millions of dollars in bonds to help finance this railroad project that failed. They really couldn’t raise as much money as they’d hoped, so they started borrowing money, including borrowing African Americans’ money from the Freedman’s Bank. Once it became clear that Jay Cooke & Company would not survive, they declared bankruptcy on September 10, 1873, and it started a wildfire.

Their branch in Philadelphia closes and shuts down. Henry Cooke is in DC at First National Bank, the D.C. branch of Jay Cooke & Company, and he flees the city and goes to his brother’s in Philadelphia. There are runs on branches, especially the Washington, D.C. branch of the Freedman’s Bank. So this starts to kind of crumble really the veneer of benevolence that the Freedman’s Bank continued to have, so that when the Freedman’s Bank really fails in the summer of 1874, it is within this broader depression. Now it is worth saying, there were about 100 banks that failed as a result of the panic of 1873, but none of them were like the Freedman’s Bank. This was a bank established first and foremost for the formerly enslaved, and I would contend the most vulnerable populations of America at this time, so they were not risky in their investments. They were not risky in wanting to save money, so they could least afford to really weather and survive the ups and downs that come with engaging in a capitalist economy such as the U.S.’s economy during the 19th century.

Hagopian: Thank you for laying this foundation for us to understand this. We have important questions to get to on the other side of the break to really bridge this history to our own time. So nobody should go anywhere. You’re going to want to hear how this history led to the situation that we are in today.

[breakout rooms]

Welcome back, everybody. I hope you had a rich discussion. We’d love to hear what you discussed in your breakout room, so please share in the chat, shout out your group, share highlights from your discussion. If you learned anything new, or got any new ideas for how you want to teach this, please let us know.

One way we support teachers in bringing this history to the classroom is with our Teaching for Black Lives study groups. We have them all over the country. It’s amazing the way we’ve built a network of resistance to anti-truth laws to see hundreds of teachers teaching thousands of students the truth about Black history, regardless of laws trying to get people to lie. So thank you all who are in study groups. And if you’re not, you might think about joining one or starting a new one. We have more than 70 this year, and you can see some of their locations there.

I am really happy to welcome Ina with us today, Ina Pannell-Saint Surin, who has co-led a Teaching for Black Lives study group in New York City for three years already. She’s also a Prentiss Charney Fellow and a good friend. I just got to meet her for the first time in New York City. That was a treat. But it’s been wonderful to work with her over the last few years in these study groups, and I wanted to bring her up with us today and ask what has been the biggest benefit of discussing the Reconstruction report as part of a Teaching for Black Lives study group?

Ina Pannell-Saint Surin (she/her): Thank you, Jesse. And yeah, kudos to you as well, and the whole team at ZEP. I really appreciate the opportunity to talk about our study group. When the call came for our study groups to consider the Zinn Education Project’s Reconstruction report, we decided to explore this. A couple of principles that ground us in our study group are the importance of learning from history and analyzing power. What we realized was that the Reconstruction era was a revolutionary time in history for African Americans that is under-taught, that is avoided, and that is misrepresented. Even when I was in school, I never learned about Reconstruction from this perspective, and did not enjoy learning about it. And now I understand why.

The report starts out stating that Reconstruction was a social, economic, and political revolution. This is such an empowering statement to share with students. We discussed the power and the depth of the Teach Reconstruction report and the lessons, the revised standards, the articles, the commentary, and the hashtag #TeachTruth honesty as a resource today, and how it connects to W. E. B. du Bois’s groundbreaking book Black Reconstruction in America, 1816 to 1880. We are asking students to reflect on how they feel learning about Reconstruction as presented in this report, and then we will write about the connections that studying this time in history has on our present day resistance and organizing against the white supremacy that we experience today.

Hagopian: Thank you, Ina. I really appreciate you sharing that. You’ve done incredible work in your group, and I hope others will think about starting Teaching for Black Lives study groups and working through some of the same questions that you have.

Pannell-Saint Surin: Well, the Zinn Education Project is doing incredible support for all of us. So my hat goes off to all of you. Thank you so much.

Hagopian: Right on, right on. We’ll talk soon. . . .

But welcome back, Justine. I wanted to ask you a few more questions. I thought before we get into the aftermath of the collapse of the bank, maybe you could just tell us a story or two about some of the people that invested their money in the bank, and what some of their hopes were, their aspirations with the bank.

Edwards: Yes, and I see there is a question kind of prompting that as well. I’m looking specifically at my chapter 5, and it is in the wake of the ratification of the 15th Amendment in 1870. I start off talking about the wave of celebrations, the excitement that African Americans are feeling at this moment, and I take this opportunity to talk about a family in Richmond, Virginia. The Harris family, and their names are Robert and Betsy Harris, parents, a married couple, and they bring their son Charles and their daughter, Mary Susan. Charles is 6, and Mary Susan is 11 at this time. Robert had opened a bank account a few days earlier, and he brought his family a few days later. Not only does he introduce his children to the Freedman’s Bank branch in Richmond, but he opens accounts for his son and his daughter. The sources for this are really fascinating, and I think heartwarming, because it shows a family taking this step toward financial literacy by opening accounts as a family.

Interestingly enough, if you look at the depositor record of Mary Susan, who is 11 at this time, it says who her parents are, where she’s born, and where she lives. But her occupation, which is in all Freedman’s Bank depositor records, says “going to school.” I just love that. The idea that she claims, or her parents claim for her, the fact that she is a student. She’s going to school, and she is quite possibly the most literate member of her family. Not only is she learning how to read, but she’s thinking about it, and she’s being encouraged to think about her own financial future by opening a bank account. So I just love this kind of story of this Black family, again, in the wake of the ratification of the 15th Amendment, making this group move toward attempting to secure their own financial futures in the best way possible. And at this time it was by opening Freedman’s Bank accounts. I think it’s a very heartwarming thought to have this Black family making this really important step.

Hagopian: Yeah. Thanks for giving us that window into who some of those depositors were and what some of their aspirations were. You discuss how the Freedman’s Bank collapse devastated Black economic prospects. I was wondering if you could talk more about what were some of the responses from Black leaders and communities about rebuilding their wealth? How did they navigate financial exclusion in the years that followed the collapse of the Freedman’s Bank?

Edwards: Well, the Freedman’s Bank failure was absolutely devastating. The Black press, in particular, really took Frederick Douglass to task, saying, “We trusted you with our savings, and even though you were in the position for a short period of time, you did not do us justice.” But increasingly, as the months and years went on, toward the end of 1874, there was a first congressional inquiry into the bank to really illuminate and excavate the reasons for the bank’s failure. That’s where we get the first accounting of the bank’s lending portfolio, and the extent to which millions of dollars were lent out to white borrowers in and around D.C. But in the years after that, Congress mandated that the trustees elect three commissioners to help liquidate the bank’s assets to try to pay depositors their money. Not much comes of that.

There was subsequently a second congressional inquiry in 1876, and this was led by Virginia Congressman Beverley. His name is Beverley Douglas, with one s, and he’s actually the Grand Wizard of the Virginia chapter of the Ku Klux Klan. And he’s a former Confederate general. So you can imagine the kind of questions that he’s asking. He has a very political reason for agreeing even to go through with these congressional inquiries. The beginning of the testimony is fascinating because he’s actually saying exactly what you would hope that someone who cares about the African American depositors would say. He’s saying that white Republicans who by and large filled the bank’s list of administrators took advantage of African Americans in their time of need, that they deserve a recompense and a full accounting of the banks’ corruption and behavior. But then he goes on and says it’s clear that African Americans were not prepared for the responsibility of democracy, the responsibility of citizenship, and the responsibility for taking care of themselves and their communities. So it’s kind of a weird juxtaposition.

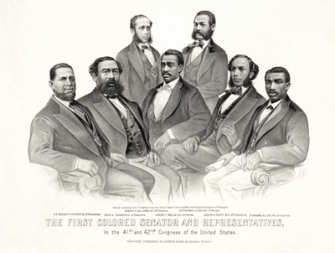

But the final congressional inquiry happened in 1879, and it was by the Black senator Blanche K. Bruce, born in Virginia but elected to the senate from Mississippi. He is actually the first Black senator to serve a full term. He recognizes that he’s on his way out. This is toward the end of congressional Reconstruction with the election of Rutherford B. Hayes, so he chooses to make this his final big move, and he calls to testify John Alvord, Frederick Douglass, Henry Cooke, many of the bank’s administrators, even a handful of Black depositors. He does not believe that he’s going to get the information that he really wants, but he just wants to put all of this on record. He spends the next year doing this congressional investigation to have on record as best that he can what happens in this period of time.

The Department of Treasury decided to issue five dispensations, the most being 20 percent of the money that depositors had in their accounts, the least amount was about 5 percent. By 1890, after these five disbursements happened, only about 48 percent of the money that depositors had in their accounts was paid off, and that was because there were all of these steps that depositors had to make. They had to prove their identity, which was incredibly hard in this period. In the 19th century they had to have a valid bank book, which was an accounting of the money that they had in their account, and they had to do so by a specific period of time. It was really tough for African Americans to even jump through those hoops. By 1901, this was the final time that conversations were had in Congress about reimbursing depositors. And it’s not until 1911 and 1912, finally, in 1913, when the final bill was introduced. But it fails. So we have this period of time when African Americans’ trust in traditional banks and white-owned institutions really starts to erode and fade. Even into the 1930s and 1940s, you have African Americans appealing to Comptrollers of the Currency, to Treasury secretaries, to attorneys general, even to presidents, even FDR. Franklin D. Roosevelt received letters from African Americans begging him for the contents of their descendants’ accounts. These records are actually in the National Archives in College Park. Barring any more interference from the executive branch, which I’m not sure about, these records are available. It’s a fascinating look at the strides that African Americans were trying to make to get money that their families had, and hopefully wanted to pass down after their death. But that didn’t happen.

Hagopian: That’s devastating history. But it explains so much. I wanted to wrap up on the connection to today. The Freedman’s Bank collapse is a pivotal moment in the creation of the racial wealth gap that persists to this day, as you write about. How did its failure shape finance and what do you see in terms of parallels with other moments in U.S. history where finance capital has been used to block Black economic progress? And what about the current role of white billionaires in the administration, how does that history inform where we are right now?

Edwards: Well, I am very wary when I hear conversations from politicians about deregulation, because historically I think about the fact that deregulation, especially in terms of the nation’s biggest banks and financial institutions, disproportionately will affect African Americans and communities of color. The Freedman’s Bank, I think, is a perfect example of this. We see this happen again throughout American history. We see the Great Depression. We see the Great Recession. So this is not past history. This has happened in the 21st century, and we are still dealing with the fallout of this. What this also tells me — and one of our attendees here writes, “This makes the keep your money under the mattress mantra make sense.” Yes, that’s exactly right. There’s a reason, and I’ve talked about this. My grandmother used to hide money under her mattress. I have family members who save money in old coffee pots and coffee cans just in case. And this economic behavior comes from somewhere, and I think it comes from this generational memory that we have about not being able to trust traditional finance.

So the Freedman’s Bank, I think, was the first example of why this continues to be so important in our conversations, again, about trust. Then the statistics kind of play this out. There have been reports recently in the past 4 and 5 years from the Department of Treasury, from the Fed, from the FDIC, that say African Americans and African American families are disproportionately unbanked and underbanked, which means that they don’t have a sustained relationship with the financial institution. And there are real consequences to that — getting mortgage credit, being able to tap into equity to help with paying for college or starting a small business, or having a rainy day fund. All of these things matter. So I think the history of the Freedman’s Bank is enduring, and I’m constantly seeing ways in which it’s playing out in our modern conversations about the racial wealth gap, about wealth, inequality, and about the kind of explosive power that the billionaire class and technocrats currently have, which really frightens me and scares me, to be quite frank, especially knowing this history.

Hagopian: Yes, such powerful history, understanding the way they looted Black wealth out of these banks and gave it to white people, white financial organizations, is crucial for understanding our own time. I can’t thank you enough for doing this research and for making it accessible and bringing it here to educators. So thank you, thank you, thank you.

While this transcript was edited, there may be minor errors or typos — if you notice something you believe to be incorrect, please contact us at zep@zinnedproject.org.

Audio

Listen to the recording of the session on these additional platforms.

Resources

Here are many of the lessons, books, and other resources recommended by the presenters and participants:

Lessons and Curriculum

|

Reconstructing the South: A Role Play by Bill Bigelow Reconstructing the South: What Really Happened by Mimi Eisen and Ursula Wolfe-Rocca When the Impossible Suddenly Became Possible: A Reconstruction Mixer by Adam Sanchez and Nqobile Mthethwa 40 Acres and a Mule: Role-Playing What Reconstruction Could Have Been by Adam Sanchez Repair: Students Design a Reparations Bill by Ursula Wolfe-Rocca How to Make Amends: A Lesson on Reparations by Ursula Wolfe-Rocca, Alex Stegner, Chris Buehler, Angela DiPasquale, and Tom McKenna Find additional resources in our Teach Reconstruction Campaign and in our national report, Erasing the Black Freedom Struggle: How State Standards Fail to Teach the Truth About Reconstruction, by Ana Rosado, Gideon Cohn-Postar, and Mimi Eisen. |

Books

| In addition to Savings and Trust: The Rise and Betrayal of the Freedman’s Bank, the following books were referenced.

Unfree Markets: The Slaves’ Economy and the Rise of Capitalism in South Carolina by Justene Hill Edwards (Columbia University Press) Before the Movement: The Hidden History of Black Civil Rights by Dylan C. Penningroth (Liveright Publishing Company) Black Power U.S.A.: The Human Side of Reconstruction, 1867-1877 by Lerone Bennett Jr. (Johnson Publishing Company) Black Reconstruction in America by W. E. B. Du Bois (Penguin Random House) The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America by Richard Rothstein (Liveright) Ellen’s Broom by Kelly Starling Lyons (Penguin Random House) |

Additional Resources

|

The Other ’68: Black Power During Reconstruction by Adam Sanchez (from the If We Knew Our History series) Freedmen and Southern Society Project, a digital collection that helps explain how Black people traversed the bloody ground from slavery to freedom between the beginning of the Civil War in 1861 and the beginning of Reconstruction in 1867. |

This Day In History

The dates below come from our This Day in People’s History collection, which contains hundreds of entries all searchable by date, state, theme, and keywords.

|

Dec. 23, 1815: Henry Highland Garnet Born March 3, 1865: Freedmen’s Bureau Established Dec. 6, 1865: 13th Amendment Ratified Feb. 5, 1866: Thaddeus Stevens Proposes Land Distribution Amendment April 19, 1866: Couple Receives Freedmen’s Bureau Marriage Certificate April 23, 1866: Freedmen Demand Equal Medical Treatment Feb. 3, 1868: First Freedmen’s Bureau Teacher Appointed in Lafayette Parish Oct. 19, 1870: First African Americans Elected to the House of Representatives April 15, 1878: Real Estate and Homestead Association Relocated Oct. 22, 1883: Frederick Douglass Denounces Supreme Court Ruling Nov. 28, 1898: First National Convention of the Ex-Slave Mutual Relief, Bounty, and Pension Association |

Participant Reflections

With nearly 200 attendees present, the conversation and chat was lively, engaging, and full of history, teaching ideas, and more. Polls showed participants included 45 percent K–12 teachers, 22 percent teacher educators, 7 percent historians, and more.

Here are more comments that participants shared in their end-of-session evaluation:

What was the most important thing (story, idea) you learned today?

The most important thing that I learned was that Black folx did not cause the downfall of the Freedman’s Bank.

The collapse of the Freedman’s Bank due to the corruption of the white board is repeated throughout history.

How economic systems, government policies, and discriminatory practices worked together to disadvantage Black Americans financially while empowering white wealth accumulation.

The most important thing I learned today was how the Freedman’s Bank collapse hurt Black communities and made it harder for them to build wealth after slavery. I didn’t realize there was a financial crisis before the Great Depression, which isn’t talked about much. It showed me how unfair financial systems can be and how history still affects people today.

The true history of the Freedman’s Bank was phenomenal. Identifying the origins of the fraud as beginning with Jay Cooke instead of seeing the blame for the failure being placed on Frederick Douglass was enlightening.

Just understanding how the Freedman’s Bank, Reconstruction, the Panic of 1873, and the backlash to Reconstruction all fit together was insightful.

What will you do with what you learned?

I will connect this to the financial struggles of the country between 1873 and 1877, which will add depth to our discussions about capitalism, racism, and Reconstruction.

I think teaching about the Freedman’s Bank will highlight the connection between capitalism and structural racism for students. It is a pretty stark example.

This information will be used in my AP class, but also in our Saturday Freedom School that seeks to bridge the gaps in education and serves students from multiple districts.

This session helped humanize the aims and support of the Freedman’s Bank. As a teacher, this session enlightened my ability to dramatize the idea of how congressional law impacted the citizenship of newly freed Africans in the United States.

I’m including the Freedman’s Bank in my Reconstruction unit, but also using it as an opportunity for students to examine current wealth gaps and narratives surrounding those gaps.

How was the format for the class?

The breakout rooms were a great way to share thoughts and meet other people doing the good work.

It all worked. I was reluctant to join a breakout room after a long work day; but it was refreshing.

The conversation, presentation, breakout groups, chat box all worked well. I thoroughly enjoyed the discussion.

It was flawless! This is without exaggeration the first time I experienced Zoom at its finest! There was no feedback or background noise and distractions, and the videos were clear. The breakout room was great, everyone was respectful of each other, lots of interesting new ideas were shared, and no one talked so long that it became boring.

Everything was good. These are well-organized and clearly thoroughly panned.

Everything was perfect, as usual.

Everything worked tonight. I would change nothing. I could go on and on learning and gathering information from tonight’s Teach the Black Freedom Struggle class and all the other ones! History has some very valuable lessons that are intentionally kept from us. But not tonight. I am very grateful for all the work that the Zinn Education Project, Rethinking Schools, and Teaching for Change do to educate and empower. This is how we will win!!

Presenters

Justene Hill Edwards is an associate professor of history at the University of Virginia. Her work explores the intersection of African American history, American economic history, and the history of American slavery. Edwards’ first book, Unfree Markets: The Slaves’ Economy and the Rise of Capitalism in South Carolina, explores the economic lives of enslaved people, not as property or bonded laborers, but as active participants in their local economies. She is working on A Short History of Inequality, which will interrogate the ways in which inequality has pervaded and structured American life.

Jesse Hagopian teaches Ethnic Studies and is the co-adviser to the Black Student Union at Garfield High School in Seattle. He is an editor for Rethinking Schools, the co-editor of Teaching for Black Lives, editor of More Than a Score: The New Uprising Against High-Stakes Testing, author of Teach Truth: The Struggle for Antiracist Education, and serves on the leadership team of the Zinn Education Project.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn