On December 2, 2024, scholar Orisanmi Burton spoke with Jesse Hagopian about his book, Tip of the Spear: Black Radicalism, Prison Repression, and the Long Attica Revolt, which argues that prisons are a site of hidden warfare within U.S. borders.

In the audiogram below, Burton describes how the Black liberation organizers from the 1960s, many then incarcerated throughout the 1970s, saw the prison as a “paradigm for how society works writ large” and made far-reaching demands for justice.

Participants shared what they learned and additional reflections on the session:

Prisons are a reflection of how power operates in society. As such, prisons aren’t institutions that are “over there.” Prisons, and the ideologies that animate them, are here, there, and everywhere.

The most important idea to me from today’s class is that education can be a weapon as much as a tool, and that we as teacher educators have to make a decision as to what side we are on in this struggle.

It was powerful to learn of how effective the Attica uprising was, and its interconnection with oppression globally — not just situated in Attica or the grievances of its inmates.

This conversation was AMAZING!

I really want to use the study of Attica in my history classes to introduce students to the idea that prisons are places where revolutionaries are created, and that they hold not simply criminals but people who are critiquing the system and can educate us.

Every session not only impacts my teaching, but unravels the damage done by whitewashed histories. I am a better teacher today.

Event Recording

Transcript

Click below for the full transcript with resources mentioned in the discussion.

Transcript

Jesse Hagopian (he/him): I’m really happy to welcome scholar Orisanmi Burton, an assistant professor of anthropology at American University. We will be discussing his book, Tip of the Spear: Black Radicalism, Prison Repression, and the Long Attica Revolt, which argues that prisons are domains of hidden warfare within U.S. borders. You’ve all got to pick this book up as soon as you can. It’s an incredible history and analysis that will definitely expand your understanding of our country and what needs to be taught in our classrooms. So welcome, Ori. Thank you so much for being here this evening.

Orisanmi Burton: Thank you so much. It’s a pleasure to be here. Shout out to the 5 percent of participants who are K through 12 students. That’s what’s up.

Hagopian: No doubt. No doubt this is the Freedom School this evening. So let’s jump into the conversation. What an amazing book. Thank you for writing this [and] for teaching us so much hidden history.

Many scholars emphasize that prisons serve a role in capitalist society as a way to manage surplus labor people, whose labor isn’t needed by the captains of industry. But you add to our understanding by really arguing in the book that prisons are war, and show how the prison system is a tool of not just warehousing people, but of political repression, particularly against Black Freedom Movements. And you illustrate this through the story of the Attica Uprising in the 1970s. So, I thought we could start there. Could you introduce us to the Attica prison, what it was, and how that history and the uprising enhance our understanding of incarceration in the United States?

Burton: Sure, I can try to do that briefly. There’s lots of different ways to approach it. Attica the prison and the rebellion are one of the most written about subjects in U.S. history, especially in U.S. prison history. But I was confident that I could bring a different perspective to it. Really, what I wanted to do was to tell the story of Attica from a Black radical and Black revolutionary perspective, and I can talk a little bit more about what that is. But for those who are unfamiliar, the dominant framing of Attica is that it’s a prison rebellion that occurred in 1971 in Attica Prison, which is in western New York. But I want to talk a little bit about some of the context that led up to that rebellion.

One, when we’re talking about 1971, we’re talking about a period of deindustrialization. A lot of solid jobs for moderately educated people are being offshored from the U.S. and sent elsewhere. We’ve got rising inflation, rising unemployment. So this is really a recipe for masses of people not having an economic function in society. And this is very much aligned with what you were just talking about, Jesse, in terms of this idea of surplus population, which is a way of talking about people who no longer have a useful function under capitalism. So the question then becomes, “What do you do with those people?” There’s a scholar named Ruth Wilson Gilmore who wrote a book called Golden Gulag, and she makes the argument that prisons were a solution to this problem of surplus population that started to intensify in the 1970s. So Tip of the Spear really tries to hone in on the political dimensions of this. Because it wasn’t just that there was no economic function, it was also that people were organizing and they were fighting for revolutionary transformation. So prisons were also being deployed as a solution to that particular problem.

As I said, Attica erupted in rebellion in 1971, but this is on the heels of several repressive measures that are passed in the United States. For instance, the War on Crime was launched in 1967, where you have the federal government passing down technologies of different control and surveillance, technologies and tactics, to cities and states all around the country. You’ve got the Counterintelligence Program (COINTELPRO), which was launched in 1956, but was revised in 1967. This is an illegal secret FBI program designed to destabilize leftist movements in the United States, specifically the Black left. And even more specifically, after 1968, they’re really trying to target the Black Panther Party. So you have, on the one hand, the intensification of these social and political movements — you’ve got the antiwar movement, the student movement, you’ve got third world liberation movements unfolding globally, and you’ve got movements like the Black Panther Party, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, the Young Lords, so on and so forth — intensifying, and so these movements are increasingly criminalized. You see more and more people that have a political consciousness ending up behind the walls.

What I want to emphasize to this forum full of educators is that the prison then becomes a site of political education. And this is really key. The state is using prisons to try to incapacitate movements, to try to neutralize movements, to try to criminalize and discredit movements. But their attempt to do that essentially backfires, because what happens is that people start to use the prison as a site of radical political education. They start to write and read and study, not just about their immediate conditions or the conditions that produce their incarceration, but in terms of studying global movements for revolutionary politics and revolutionary struggle and decolonization. And that global study really informs the sorts of activism that they engage in.

Hagopian: Yes, I love that framing. And I really appreciate you giving us that historical and global framework for understanding Attica, especially understanding how prisons are used to disrupt social movements — not just warehousing surplus labor, but also specifically aimed at Black struggle. You mentioned COINTELPRO. We have an amazing lesson for educators on how to teach about COINTELPRO that people should look up.

The Attica Uprising is often remembered as a singular event, but in your book you present it as part of a broader ongoing struggle that you call the Long Attica Revolt. I was hoping you could explain more about this concept, what it means and why it’s important for understanding the uprising’s legacy.

Burton: Attica is typically framed as a 4-day rebellion that emerges on September 9, 1971, and is crushed by a violent state assault on September 13. It’s typically framed as being largely confined to Attica Prison, the singular prison in western New York. I think we’ll talk more about this later. It’s typically framed as though the primary demands of that rebellion were about improving prison conditions. So part of what the book is trying to do — again taking Black radicalism and Black revolutionary politics as a source of knowledge seriously — it’s an attempt to decarcerate our understanding of what that movement was about.

There’s different kinds of incarceration happening. There’s the incarceration of physical bodies, incapacitating them in space and time. But there’s also the incarceration of certain forms of knowledge. Ultimately the book is arguing that what many call mass incarceration was really about containing the spread of a certain kind of consciousness, a certain kind of politics. The question of knowledge then becomes decisive. So the Long Attica Revolt is just a name I gave to something that people were already talking about. Part of how I wrote the book was that I talked to people who were involved in these movements, people who were involved in these struggles, and everything that’s in the book is what I learned. There was very little in the book that I could have articulated before I started to do the research.

At the beginning, I’m just feeling around, trying to find people who were involved, asking questions. I would ask them about Attica, this rebellion that happened in Attica Prison in September of 1971, and they would answer my question by talking about earlier rebellions that happened in the Tombs. The Tombs is the name of a jail in New York City. They called it the Tombs. Or they would answer the question by talking about Auburn, which is another prison rebellion that happened. Or they would answer the question by talking about their organizing in the Black Panther Party. In other words, the people who were involved in these struggles, the way that they narrate these struggles does not cleave to the official record of how Attica is remembered.

Part of what I learned from talking to people who were there is that Attica is really this long distended movement or genealogy of prison struggle, which is itself a discrete part of actually a much longer Black radical struggle that’s tied to slavery. It’s tied to resistance to slavery. It’s tied to resistance on the slave ships. It’s a Black radical tradition that speaks to the ongoingness of a struggle for actual human relationships that is in this world, in which these relationships are deformed by different forms of oppression and repression and violence.

Hagopian: Yes, and we’re glad you did. You talked about how we need to examine the ideas of the people who are part of that struggle, so I want to go there now. you describe the Attica revolt as “a revolutionary upheaval that made the maximum demand of the abolition of prisons, the abolition of war, the abolition of racial capitalism, the abolition of this concept of the white man, and the emergence of new modes of social life not predicated on enclosure, extraction, domination, or dehumanization.” I love that description. Then you also write about how often people portray incarcerated people’s demands as just wanting to be treated humanely in the current system, in the current prisons. How does your history complicate that popular perception of incarcerated people and their political agency?

Burton: There are a couple things. One of the first things is that we need to understand what the Black radical theory of prisons is, what the prison is, and what its function is. What’s its place in society? The typical liberal way of understanding what prisons are is [that they are] some institution over there somewhere where people who are convicted of crimes are placed, etc., etc. The Black radical theory of prisons is not that the prison is some place over there, it’s that prisons are actually a distillation of the power relationships of the larger society. In other words, the key intellectuals who are being targeted by this war that I’m talking about argued that if you study the prison you actually understand how power works in the broader society, that prisons are actually the paradigm for how society works writ large. That was their theory of what prisons were, and in dealing with their movement they were struggling against the prison, but they were really attempting to participate in broader movements for social transformation globally. The prison then became a key site for engaging in those struggles.

Part of those struggles was to struggle for better prison conditions, because prisons function in a genocidal manner. And I mean that literally. If you were to read Raphael Lemkin’s canonical definition of genocide, we would see that prisons carry out a genocidal function. And they made this argument in the 1970s. Part of what they needed to do was struggle to ameliorate prison conditions, and that’s typically what we focus on. And it’s important. But it’s not all they were arguing for. I call the struggle to transform prison conditions. I call that the minimum demands. That’s the basic necessity of what they were arguing for, an end to slow genocide. But they also had these maximum demands where they were thinking in really capacious ways about: How do we create a new way for humans to relate to one another? How do we create new forms of intimacy? How do we create societies where caging large amounts of poor people is not necessary? How do we create a society that does not require war and exploitation? How do we create a society where there’s not artificially imposed scarcity that necessitates that people will have to commit crimes in order to survive? These are some of the contradictions that they were working through, and it’s hard to frame that within a narrow pragmatic incremental reformist approach. And so a lot of people just don’t deal with it because they feel like it’s unrealistic. So part of what I wanted to do in the book is to give people an opportunity to engage with this population who is thinking in really capacious ways and creative ways about what revolution looks like and how to actually make that happen, and to show their willingness to make sacrifices, to shed blood, to make that happen. That’s where I go with that tension, and I try to show it and lay it out in the book. I’m trying to be brief here.

Hagopian: Yeah, no, I appreciate that, so we could get some more questions. But no, that’s spot on. The state’s response to Attica was just absolutely brutal, from the initial crackdown to disinformation campaigns, and the aftermath meant to discredit the uprising. So, how does this historical example inform our understanding of how states respond to revolutionary movements more broadly? And how did the suppression of the uprising shape the prison system’s evolution in the following decades?

Burton: Here’s what I want to offer. The response to Attica is really multifaceted. It’s too detailed to really get into all of it here, but I think it’s important. The part that people fixate on — and for good reason — is the brutality of the repression, which was extremely brutal, and it was designed to be publicly consumed. In other words, the state was trying to send a message to people all around the world to say, “Look, if you resist, you will be brutally punished.” That was the message. And that’s usually where the conversation about the repression stops.

One of the outcomes of Attica is the introduction of these very, I call them seductive programs, that are designed to enlist more public support from people outside of prison walls to get them to come into prison and to buy into the possibility of prisons creating a reformed and rehabilitated subject. But there was this other side to it of using prisons as a way to depoliticize and de-radicalize this population and enlisting the volunteer support of educators to do so. This is one among many examples of the proliferation of programs that happened after Attica, and I argue that it needs to be understood within the context of a counterinsurgency, an explicitly designed very sophisticated counterinsurgency. So, while most people focus on the repression, I think, in this instance, with this audience, it would be most useful for us to consider how education was being used as a tool of oppression. Similarly to how colonial education systems have historically always been used as tools of oppression all around the world. There’s nothing inherently good or bad about education, it’s just a tool and it can be used in different ways. I think that’s what I would love for folks here to struggle with.

Hagopian: Yeah, I appreciate that reframing. And I think that’s a question that we need to continue to struggle with and to see the ways the education system reproduces a lot of the same logic and constraints that the prison system does. Thank you for that.

I wanted to shift to looking at the discussion of gender that you have in the book, which I find really fascinating. You wrote in Tip of the Spear that the Attica revolt was “not an attempt to appropriate the trappings of white patriarchal power to attain parity with white man, or become the man at the expense of others’ autonomy or dignity. It was an effort to chart a new course for what revolutionary manhood or humanhood, as one survivor named it, could become.” Can you talk about how narratives of racialized gender inform the repression of incarcerated people, and how their resistance can upend traditional or hegemonic conceptions of gender? Specifically, how do these acts of resistance challenge not only racial but also patriarchal systems of power?

Burton: I could talk about this forever. It’s hard to be brief. I’m going to do my best. One of the things that I try to emphasize is the different practices. Well, there’s a couple of things. The prison is a patriarchal regime. It’s intensely hierarchical, [and] that hierarchy is enforced through violence. The book is primarily about men, and part of why the book is primarily about men is because prisons are organized around a very rigid sex gender binary. In order to write the book in a rigorous way I had to develop these networks of affiliation, and I had to draw a boundary around the book somehow. If I were to then study women’s prisons, the book would have taken me another decade to write. So I wanted to write a book about men, and in doing so I wanted to really think about the gendered struggles, the gendered life, that is happening. There’s this tendency for us to think that when we’re talking about gender that means we’re talking about women, or that we’re talking about gender nonconforming people. There’s this unspoken assumption that men are cisgendered, assumptively heterosexual, especially Black and men of color. That is like an unmarked gender category. There’s nothing worthy of gender theorization there. So I was trying to push back on that.

The other thing is that incarcerated men talk about gender all the time. They talk about gender all the time. They might not talk about gender in the way that we’re socialized to talk about gender in the U.S. academy. They don’t necessarily have the correct, “correct,” most up-to-date, language. Sometimes that can be a reason that people use to dismiss them, because they didn’t say the right thing. Part of what I wanted to do is to focus on what these men were doing, how they were living gender. Because gender is a practice that you do, that you do with other people.

Hagopian: That’s so powerful. I love the way you shifted the lens there and expanded our understanding of the ways gender is produced, reproduced, and struggled against, and how we can fight to create new definitions. That’s so valuable!

We just have a minute here, but if you could touch on this last question before we go into breakouts, I’d appreciate it. Many educators are aware of the school to prison pipeline, but may not see it as connected to this historical process of repression that you have described. So I was hoping you could talk more about how teachers can draw historical parallels between systems of punishment in schools and the broader history of political repression. Do you see any implications for what this means for teachers and what they could do differently?

Burton: I mean, one of the things that I think is most interesting about the prison is what I said earlier about the extent to which the prison was becoming a site of political education. Also, thinking about how enslaved communities developed modes of political education under some of the most difficult conditions imaginable. So thinking about education as something that can be both a tool and a weapon, a tool that you can use to get what you want and a weapon that can be used against you, and being critical about that dynamic and the role that educators play in terms of the intensifying move to divest education of all sort of political substance, of all of its radical substance. And how, even within that context, educators still can do amazing work, because we have models throughout history of them doing that.

In terms of the school to prison pipeline, I think that can be a useful framework, but I think sometimes it’s misleading because it doesn’t highlight the extent to which the school itself can be a carceral site, and the extent to which prisons can be sites of liberatory education. So again, if we think about the prison as a paradigm for how power works, some of these notions of school to prison pipeline and that distinction, they kind of dissolve.

Hagopian: I’ve heard educators talk about the school to prison nexus and how they’re much more connected, and there’s aspects of each within each other. So yes, thank you for that framing.

[breakout rooms]

Welcome back, Ori. Let’s jump back into this conversation. There’s just so much. We can’t even get to all the lessons in this incredible book, but you wrote an open letter to prison officials and you revealed that Tip of the Spear is being banned in several state prison systems, labeled as “contraband,” and that people who are caught with it can be punished. In your book you quote Jomo Omowale, an Auburn and Attica survivor discussing the censorship of George Jackson’s Soledad Brother. This just reminded me how prisons have long been sites of extreme censorship and intellectual repression. Now we’re seeing similar efforts spill beyond the prison walls with schools and states banning books about systemic racism, on Black history, and about gender and sexuality, as well. How do you see these acts of censorship connected? And what does this say about the broader societal attempts to control knowledge and historical memory?

So censorship has always been a tool of control within the prison system because, of course, the best way to control someone is to control what they think. You don’t necessarily have to control their behavior if you’re already controlling what they are thinking and what they have access to. The story you mentioned about Jomo Omowale is really important because he didn’t say that George Jackson’s book was being censored. Well, he talked about that history, but what was happening at that moment was that prison officials had introduced more access to television into prisons as part of a coordinated strategy to get people to stop reading.

This goes back to what I was saying earlier about these seductive methods that, on the one hand, can be presented as a benefit, as something that’s designed to help. But actually there’s an underside to it that’s designed to demobilize people. So the television and access to television and other distractions was introduced as a way to try to depoliticize people. So my book is being banned in prisons all over the country. A prison official in Florida said that it might incite a riot and that’s why it’s being banned. To that in my open letter I wrote, “The real issue is not that my book may incite riots, but that your hold on power is so fragile, so tenuous, so devoid of legitimacy, that mere words on a page may be enough to make your cages of concrete and steel go up in flames.” So that’s a little bit of the response. But ultimately I wrote that, “Yeah, you have a good reason to ban the book. I would ban the book if I were you, too. But that has to do with the conditions that you’re enforcing, and less to do with what the book is about.”

Hagopian: No doubt. Yes. It’s incredible! I really love your framework of how looking in the prisons is like a time machine to look at our future. That’s why we all on the outside need to be linking arms in solidarity with those on the inside. That’s such an important framework that we all as educators need to think through more about what that means concretely and how to organize that. So I appreciate you introducing that.

Let’s see, there was a question about genocide in the chat that we discussed in the breakout. I just thought I’d give you a second if there’s anything you wanted to add.

Burton: If we were talking about the movements of the 1960s, the Black Panther Party was organized around combating genocide. The idea that that oppressed groups in the United States are subject to genocide is a longstanding discourse. We can trace this all the way back to the Civil Rights Congress and their book that they submitted to the United Nations, We Charge Genocide, which made a case for Black people as the historical targets of genocide, which is really building on the coining of that term. It wasn’t a term until 1945, when Raphael Lemkin coined that term genocide. He defined it as a coordinated plan of different actions aiming at the destruction of essential foundations of the life of national groups. That’s one of the ways that he defines it. Then he lays it out in We Charge Genocide. They lay out how Black people, specifically in the U.S., are the targets of genocide. Part of how the prisons are functioning as genocide is at the level of consciousness, which is to try to destroy Black nationalist consciousness, to try to destroy the idea that Black people are a people, are a sovereign people who have the right for self-determination. If you can destroy the very idea that Black people are a people who have the right to self-determination, then you’ve destroyed the foundations for the reproduction of a national group. That’s just an overly theoretical description of how prisons are functioning as genocide. But all of these resources are here for us. So I would urge you to look at the We Charge Genocide petition, which Paul Robeson and W. E. B. du Bois were involved in. I would urge you to look at Raphael Lemkin’s coining of the term, because if you read what he wrote about what genocide is, it’s clear that a lot more things are genocide than maybe we are used to considering.

Hagopian: Excellent. Thank you for adding that. What a conversation. I have so many notes I’m taking here to follow up on and read more about and connect more. I had one more question for you this evening. In the chapter titled The War on Black Revolutionary Minds, you explore the relationship between state violence and intellectual resistance, and you discuss the ACTEC Program, which used psychotropic drugs as part of a broader strategy to pacify and suppress incarcerated individuals. And that wasn’t even the only program like it. You describe several other programs that are similar in many different prisons. It’s just horrific abuse that prisoners had to undergo as part of this effort to undermine radical movements.

You write, “These academic experts aim to manipulate and remold the most intimate parts of people’s personalities. If this could be achieved, perhaps they could also reshape their loyalty, their political affinities, their personal aspirations.” So, despite these efforts to manipulate consciousness, many incarcerated individuals engaged in remarkable forms of intellectual resistance and organizing and sustaining revolutionary ideas. How does the ACTEC Program illustrate the state’s attempt to suppress this intellectual resistance? And what can we learn from the ways incarcerated people resisted such oppressive tactics, both historically and in contemporary contexts?

Burton: That’s a big question. This is from Chapter 6. Part of what I tried to show is the role of academics in doing research on a particular class of imprisoned revolutionaries to try to figure out: Why do they think like this? Why aren’t they responding to our attempts to suppress them? Why aren’t they scared of us? Why are they so bold? These are literally the questions they’re trying to ask, and they do all kinds of tests and experiments. I mean, there’s lots to talk about that. But I suppose I want to end on a note of emphasizing one.

The extent that these folks were willing to go to try to answer these questions in some ways is an index of how effective and threatening these movements were. That’s one thing that I want to emphasize, that these movements were so effective that they had to get professors from all over the world to study these folks and to try to break them. And they failed. A key figure in Chapter 6 is a guy named Masia, an elder brother who’s still alive. He’s 81 [and he] survived some of the most repressive, draconian, dystopian conditions one can imagine. I write in the book that he still manages to smile often. This brother has no reason to still be intact, but when you talk to him he’s intact. Intellectually he’s intact. He’s still political. He’s intact spiritually and morally. When I go to visit him he lives in a home for the elderly, and everyone knows him. He teaches martial arts to the elders outside. In other words, this is an example of the state marshalling all of these techniques, and some of the most dystopian stuff you can imagine, and just failing to destroy this person. Just failing to destroy this person. I find immense humility and inspiration from brothers like Masia, and I tried to do historic justice in Chapter 6.

One thing that I take away from this is that these experiments ultimately failed to produce the intended result, which is to turn people into just obedient, mindless slaves. That was the desire, and they failed. We have people who are walking among us right now who are living testaments to that, and I tried to include them and do their stories justice in the book.

Hagopian: Thank you for doing that. One of my greatest inspirations is a man named Shujaa Graham, who joined the Black Panther Party in prison at San Quentin and came out and continued organizing. As a young teacher in Washington, D.C., hearing him come and speak out against the death penalty and tell stories about how prison guards beat him and spat on him and told him after King was assassinated, “We’ll kill all your leaders. You’re never going to amount to anything,” and him standing there and just saying, “San Quentin, look at me now.”

There are some incredibly strong and brave people that have survived those institutions and are training generations in the struggle. Thank you for bringing their voices forward in this brilliant book. I hope everyone will go get this book and use it and develop lesson plans and pedagogy around it and share that with us. Thank you so much, Ori, for being with us today.

While this transcript was edited, there may be minor errors or typos — if you notice something you believe to be incorrect, please contact us at zep@zinnedproject.org.

Audio

Listen to the recording of the session on these additional platforms.

Resources

Here are many of the lessons, books, and other resources recommended by the presenters and participants:

Lessons

|

COINTELPRO: Teaching the FBI’s War on the Black Freedom Movement by Ursula Wolfe-Rocca “Riots,” Racism, and the Police: Students Explore a Century of Police Conduct and Racial Violence by Ursula Wolfe-Rocca Teaching Social Activism in Prison: The Leap Manifesto and Incarcerated Youth by Rachel Boccio What We Don’t Learn About the Black Panther Party — but Should by Adam Sanchez and Jesse Hagopian ‘What We Want, What We Believe’: Teaching with the Black Panthers’ 10-Point Program by Wayne Au |

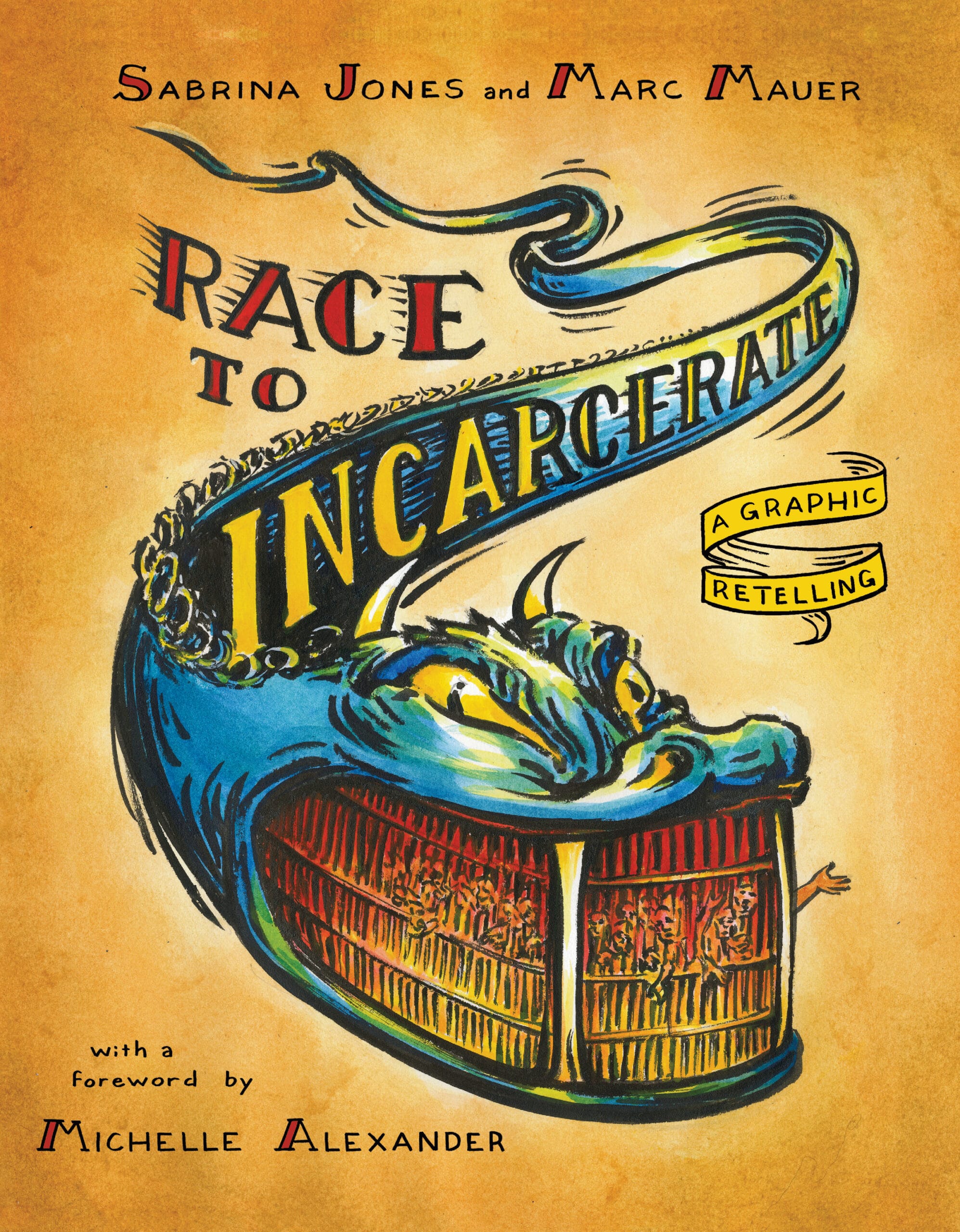

Books

Video

TED-Ed lesson by Orisanmi Burton, directed by Tomás Pichardo-Espaillat.

Additional Resources

| Attica Prison Uprising A resource list with links to articles, books, primers, films, and websites about the Attica prison uprising for the classroom. An Open Letter to Prison Officials on the Censorship of “Tip of the Spear” Attica Was More Than a Riot. It Offered a Framework for Revolutionary Struggle. Certain Days: Freedom for Political Prisoners calendar Howard Zinn on Prisons and Prisoners The Black Panthers: Vanguard of the Revolution |

This Day In History

The dates below come from our This Day in People’s History collection, which contains hundreds of entries all searchable by date, state, theme, and keywords.

|

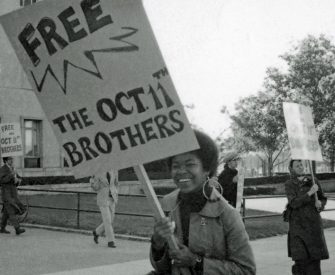

Sept. 25, 1840: William Freeman Imprisoned and Challenged Convict Leasing Dec. 6, 1865: 13th Amendment Ratified Oct. 31, 1891: Coal Creek War Dec. 17, 1951: “We Charge Genocide” Petition Submitted to United Nations Oct. 15, 1966: The Black Panther Party Founded April 6, 1968: Bobby Hutton Killed by Oakland Police Nov. 20, 1969: Alcatraz Occupation July 1, 1970: The Lincoln Pediatric Collective Forms to Serve Bronx Community Feb. 12, 1971: Raiford Florida State Prison Uprising Sept. 9, 1971: Attica Prison Uprising Oct. 11, 1972: D.C. Jail Uprising Aug. 10, 1975: Prisoner Strike Leads to Prisoners’ Justice Day Aug. 15, 1975: Joan Little Acquitted July 4, 1976: Marion Prisoners Stage Bicentennial Hunger Strike April 19, 1989: “Central Park Five” Arrested Nov. 22, 2019: Harlem Park Three Released from Prison |

Participant Reflections

With more than 160 attendees present, the conversation and chat was lively, engaging, and full of history, teaching ideas, and more. Polls showed participants included 42 percent K–12 teachers, 19 percent teacher educators, 5 percent K–12 students, and more.

Here are more comments that participants shared in their end-of-session evaluation:

What was the most important thing (story, idea) you learned today?

Despite all the attacks within the prison system, those incarcerated were still able to fight and gain political knowledge and power.

The story about the [Attica prisoners] sleeping under the stars and taking walks during the rebellion really made me think about what freedom is and challenged me to think about the uprising differently.

The most important thing that I learned is how the truth is often hidden and blocked from the public in order to create a false image of an event or group.

Attica as an example of the “backfiring” of putting political activists in prison.

I think my most important takeaway was the way that some prison reforms, such as education programs and TV access, perform the function of counterinsurgency.

The relationship between prisons and genocide.

Prisons are a form of political education and bringing in teachers and professors to provide education to prisoners may seem like a progressive reform, but in reality it can serve to delegitimize the autonomous political education existing amongst the prisoners.

What will you do with what you learned?

I plan to use excerpts from Tip of the Spear in my Saturday Freedom School, where we will have primary source speakers from the Long Attica Revolt in intergenerational conversation.

I teach an hour on Attica. I will now not only feel empowered to teach about it during the Civil Rights Movement unit, but also reframe the purpose of prisons and education.

I hope to use the Attica uprising, in particular, as an example of intellectual resistance.

I plan to incorporate this book in a class I am teaching next term in teacher education. I will facilitate the comparison of prison system to K–12 schools, emphasizing the collective liberation efforts of those in prisons and the students/families/communities within K–12 schools.

I intend to create lesson plans that trace a line of political backlash from incarceration enthusiasts against human rights starting with policies implemented in prisons.

Teach the long Attica struggle, rather than only events from the four days of the uprising.

I think this will really change how I plan to teach Reconstruction, how I discuss the emergence of mass incarceration with students, and how the threads of incarceration carry throughout history. I’m also revisiting how I plan to teach about protest movements post-WWII.

I will continue to advocate for and work with university students who have come home from prison.

I will absolutely be adding so many things from today to multiple lessons (intended lessons, anecdotes, even vocabulary), but I will always carry it with me as I constantly re-evaluate myself and my teaching. I will force myself to answer, “Am I fighting, allowing, or cooperating with the incarceration of education?”

How was the format for the class?

Excellent format, and the breakout rooms were wonderful.

I enjoyed the breakout room because I got to connect with people and get more in depth on the content. I even got book recommendations, which are always welcome.

Tonight the chat box was on fire with thoughts and ideas.

I really enjoyed tonight’s session. I knew little about the topic, and the format allowed me to ask questions and to sharpen my understanding.

The breakout rooms are always great places to hear from others around the country and gain new insights.

As usual, the entire thing worked. Loved it all.

Presenters

Orisanmi Burton is assistant professor of anthropology at American University. His research examines the imbrication of grassroots resistance and state repression and explores the collision of Black-led movements for social, political, and economic transformation with state infrastructures of militarized policing, surveillance, and imprisonment.

Jesse Hagopian teaches Ethnic Studies and is the co-adviser to the Black Student Union at Garfield High School in Seattle. He is an editor for Rethinking Schools, the co-editor of Teaching for Black Lives, editor of More Than a Score: The New Uprising Against High-Stakes Testing, author of Teach Truth: The Struggle for Antiracist Education, and serves on the leadership team of the Zinn Education Project.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn