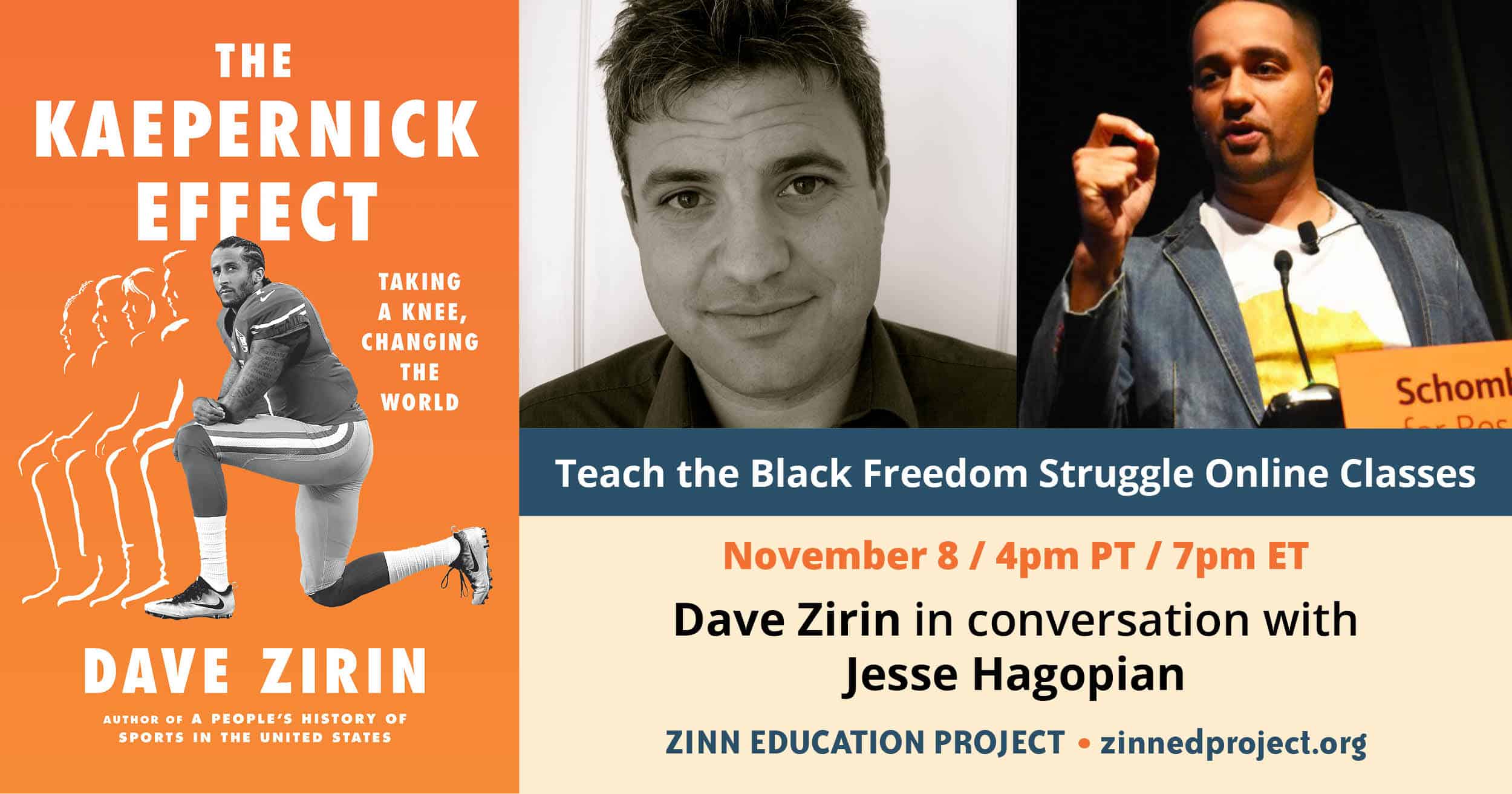

On November 8, 2021, author Dave Zirin joined educator Jesse Hagopian in dialogue for the Zinn Education Project’s Teach the Black Freedom Struggle online people’s history class to discuss his new book, The Kaepernick Effect: Taking a Knee, Changing the World. Through extensive interviews with high school and college students around the country, The Kaepernick Effect is dedicated to understanding how young people were inspired to launch a social movement from below.

Here are a few reactions from the participants:

Thank you so much for this opportunity! I want to get the book by Dave Zirin and continue learning and #teachingtruth!

I didn’t know how much could be taught through sport protests.

I was so tired to begin the session. Left with enough energy to flow.

I thought this was one of the most participative, inclusive feeling webinars that I have ever attended. It did not feel like a group of over 200 ‘anonymous’ participants and instead it seemed like a small group who were explicitly invited to participate & who did. It all worked well for me. Thank you.

Video

Video of the full event, except the breakout sessions.

Transcript

Click below for the full transcript with resources mentioned in the discussion.

Transcript

Jesse Hagopian: We’re lucky today to be joined by Dave Zirin, the Nation’s sports editor and author of eleven books now, I believe, on the politics of sports. He is joining us today from Barcelona. What’s up, Dave?

Dave Zirin: Hey, it’s great to be here. It is 1:05 am in Barcelona, and I could not be happier to be spending this time with everybody here. Seriously, Barcelona has got nothing on this Zoom call, I swear.

Hagopian: You out there running with the bulls?

Zirin: No, because that would be speciesist. Just more chillin’ with some paella and some sangria and doing my thing. No, but in all seriousness, in Barcelona the 1992 Olympics were held, and it’s often held up as a model of how the Olympics should be run. There’s a lot of ugly underbelly to that 1992 Olympics Barcelona story, so I’m actually doing some investigation. Yes, there is Sangria involved. But I’m doing more investigation into the 1992 Olympics. They have a museum here and an archive here, and that’s my focus.

Hagopian: Right on, thank you for making the time. I really appreciate that. I love the new book you just dropped, The Kaepernick Effect. There’s a lot of reasons and I’m excited to dig into the book. But, in the beginning of the book, you write that after interviewing many of the people in the book, many of them young people, you said that you understood the Kaepernick effect was not the result of someone else’s protest, but a cause, a catalyst, for something far greater. You really thought about what the whole concept of the Kaepernick effect really was, so can you tell us what is the Kaepernick effect?

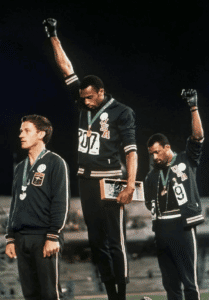

Zirin: Wow. I mean, the best way to tell you, and the best way to make it clear, would be to start by saying I was having a conversation with John Carlos. He was, of course, one of the 1968 Olympians who raised his fist on the medal stand. I wrote John’s memoir with him and he’s just not only a dear, dear friend, but a total hero to me, and an inspiration. John Carlos said to me in a very offhanded way, “There were a lot of people who raised their fists in 1968, after we did at athletic events. That happened a lot.” And it really made me think for a second, my goodness, I don’t know any of those stories. That’s been completely thrown into the memory hole. We’re not taught that and we don’t know it. One reason is that nobody really recorded it and took the time to do what I call the Studs Terkel work of actually going to the folks and actually doing those kinds of interviews and really learning about how the real motor of history, the real hand on the lever of history, involves hundreds of thousands, millions of people whose names we’ll never know. But I think one of our jobs as educators or as writers is to get as many people as possible to know these names. Partly because it takes away from the passivity with how we study history sometimes — like history is made by other people, great people, usually great men, and the rest of us are just sort of spectators to the story of history, the greatest story ever told. That’s not really how history changes, though. History changes through the actions of masses and masses of people. Sure, great individuals arise from those masses, but the work of the masses needs to be recognized and told so we can learn the lessons.

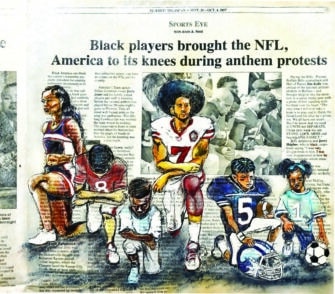

One of the great lessons is that history is not just about one human being, it’s about what we all do collectively. So I started thinking a lot about all the young people who took a knee after Colin Kaepernick did, and all these one-off stories, a lot of which I wrote for the Nation about this particular high school in Detroit where kids got beer thrown on their heads and bottles thrown at them. Or thinking about other stories in small towns like Beaumont, Texas. Just all these stories, these amazing stories. I was like, we need to have a book that brings all of these stories together. So that was the first motivation for the book. But then that changed as I was working on it, after the police murder of George Floyd. I went back and I called all the people I’d interviewed to see how they were doing and how they were feeling, and they were all either at demonstrations or organizing people for demonstrations. That made me realize that while many roads may have led to the summer of 2020 and the largest protests in the history of the United States, one of those roads runs straight through the athletic fields of the United States. And that, to me, was a story that needed to be told.

Hagopian: Yeah, no doubt. I’m so glad you told it, and I’m hoping you can share some of those stories with us. What are some of your favorite stories? I love how you organize the book in terms of the first third is high school students, then college students, and then pro athletes. But I’m thinking, especially for this group, we can focus on the high school students in the book, whose courage to kneel during the anthem really was catalytic for this national movement. I’m especially interested in the role of Black girls and young women athletes whose leadership played, I think, a really decisive role in propelling this movement forward.

Zirin: Yeah, a couple of things I want to share. First, I interviewed dozens and dozens of people, and most of the people I talked to for the book actually are high school students, and that was very much on purpose. I could have done a whole book about pro athletes who took a knee during the anthem to protest racial inequity and police violence. I could have done a whole book about college students. But I wanted the book to be proportional relative to my research. And in my research, what did we see? We see tons of young people, tons of people who aren’t old enough to vote, who are the ones propelling this movement. You see an incredible interaction with the young person in their community after they take that knee, in terms of the conversation it starts or the backlash it provokes. Also, when I was looking at the movement nationally, it was really inspiring how many young women were part of the struggle, and that needed to be represented in the book.

Then it was, frankly, a little bit surprising. I’m just going to be very honest, how many cheerleaders were part of the struggle. I knew the cheerleaders needed to be represented in the book as well. See, that’s so important, for the book to have proportionality, because I really wanted it to represent what I think was, in a lot of respects, a subconscious mass movement in this country of people in big states and little states, blue states, red states, small towns, big cities, taking a knee and facing very, very similar repercussions for it, very similar backlashes for it. And I’ll tell you, I do want to tell stories from the book, but I’ve got to say, when I started writing the book I felt pretty pessimistic about the state of the world. I mean, the pandemic was just starting and I wasn’t feeling great about some of the choices headed up for the election. But after talking to these young people I really did go from being pessimistic to optimistic because the young people, the young people listening to this right now, I mean, they were so tough in the face of so much crap that was thrown at them. They were so strong in the face of so many people who told them not to do anything. And there’s no other word for it, they’re old souls.

I was talking to young people the name when I asked them, “Who’s your biggest inspiration for taking that knee during the anthem and for risking everything what you risked?” When I talk about risk, I mean, we’re talking about not just getting in trouble with your coach or the school administrator, we’re talking about violent threats against them, against their family, against the school. Stakes are really high when they’re doing this, and their courage in the face of that was so intense. So, as I was saying, when I asked, “What was your reason for doing this? Who inspired you?” I thought the name I would hear most of all was Colin Kaepernick. But that’s not the case at all. The name I heard more than any other was Trayvon Martin. In speaking to them, it really clicked with me like, wow, here I am talking to these folks in 2019, 2020, and Trayvon Martin was murdered by George Zimmerman at age 14 in 2012. So that’s eight years earlier. If I’m talking to a 17 year old, and they’re saying that their inspiration was Trayvon Martin, that means they were nine [when Trayvon was murdered] and that means it marked them in a very sincere way. It reminded me so much of stories that I’d heard about that first generation of civil rights activists in the 1950s. I’m speaking about Emmett Till, who was also 14 years old, that’s one similarity, when he was also violently killed because of the color of his skin. That’s, of course, another similarity. But the biggest similarity . . .

Hagopian: And Rosa Parks famously credited him [Till] with her decision not to move.

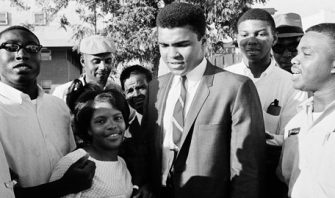

Zirin: Yeah, and Muhammad Ali said that that was the start of his radicalization, being a child and seeing his face in Emmett Till’s face when he would look at him. The biggest similarity, though, is that there was no justice. It’s like, okay, you can brazenly kill us and we cannot receive justice from this society. That’s what they were saying to me. And that’s what made it for them this thing where they had to do something, and they were just so brave in the face of what they were dealing with.

Someone joked with me that the book should be called What to Expect When You’re Protesting, like What to Expect When You’re Expecting, because it’s got all of these scenarios about what do you do if your coach supports you; what do you do if your coach stabs you in the back; what do you do if your friends don’t talk to you anymore; what do you do if your family gets a death threat. And these people, they talk me and they talk the reader through all of these remarkable scenarios that they’re forced to deal with, and that they dealt with with a lot of courage. That’s why, if people have read my other books, I don’t know if you have or not, but my voice tends to be in there pretty centrally. But this book, I took a massive, massive step backwards and really looked more at folks, just listened to them. So it’s their words on Front Street, their experiences on Front Street.

The last thing I’ll say is that that’s also why I am donating proceeds of the book to the organization Serve Your City, which is an amazing mutual aid group in D.C. run by my dear friend Maurice Cook. Because the idea for me is that the courage of these young folks needs to be paid forward, and people my age can’t just sort of cross our arms and say, “Yay, young people save us, I’m going to have a drink.” But we need to figure out ways to center them, center their voices, center their struggles, but also figure out how we can support them educationally, materially, organizationally. Whatever skills people like you and I have developed along the way, over the years, we need to bring them to bear for them and for their work.

Hagopian: Right on. You said that you started the project off pessimistically about society and you ended very optimistically after talking to these young people. So following up on that, I just hope you could say a little bit more about what you learned about the consciousness and the political beliefs of young people by doing these interviews, and then how the 2020 uprising impacted that consciousness?

Zirin: Great question. I mean, this generation is less tolerant of intolerance than any generation in the history of the United States. That makes them both very precious and it also makes them very tough, because we live in a society that mocks people for giving a damn, that mocks people and calls us the woke mob. They use the word woke as a racial slur, even when it started in the Black community. That’s what it’s become in their hands, and to have young people care in the face of that, and to have them act in the face of that. . . The story I always go back to is when my daughter was in eighth grade, there was a call for a school walkout at her public school. They were in junior high and the principal of the school said, “Okay, you can have the walkout,” because there were so many, too many, students who were ready to do it, “but we’re going to walk out to the football field and hear talks.” So they weren’t really walking off of school grounds, they were walking to another safe space. And that led to a protest inside the school of the principal not letting them walk off of school grounds.

This idea that they’re playing chess and they’re . . . what I learned, you asked the question so well. What did I learn speaking to them? I learned that they’re going to fight for a better world and a different world, and I think because of that they’re going to be unapologetic about doing so. I also think that they were the political weathervane for those 2020 protests, which, you know, the size of those protests, the biggest protests in U.S. history, took a lot of people by surprise, a lot of people. That there were protests in all fifty states took a lot of people by surprise. If we had been paying attention to what these young folks were doing throughout 2017, 2018, and 2019, and the way they were really spreading the word of you can take a knee during the anthem and really hold up a mirror to this country, you can have a conversation about the gap between what this country says it represents and the lived experiences for Black and brown people in one of the most unequal societies the earth has ever produced. If you can do that, and spread that word, town by town by town, and if our media in this country was an actual media and was tracking how that was going, then 2020 would not have surprised anybody. It would have said the groundwork has been laid.

And similarly, this generation, if we had paid attention to what they’d been doing in 2017, 2018, and 2019, and we had followed the backlash that they would have to receive — and how not just uncomfortable but how violent it made certain sectors of their communities — when they were dared [or] challenged on why is this country is so racist and what are you doing about it to make it different? If we’d seen how those people in these small towns did not say, “Well, let’s agree to disagree,” or, “Well, let’s get together and have a conversation about it,” but instead responded with that level of vitriol, and the looming threat of violence. If we had paid attention to that, then these 2021 so-called CRT debates, that wouldn’t have caught people as much off guard either. Because that was there in all of these small towns. I think that it twisted and thought that stuff was concentrated at Trump rallies, when it was concentrated everywhere. Whether red state or blue state — you know this better than anybody, Jesse — you can be Seattle or you can be Beaumont, Texas, and there are going to be people there who feel like white supremacy should be the order of the day and any challenge to that is inherently deeply, deeply offensive, and they feel that offense in the marrow of their bones. And you’re seeing that level of twisted, distorted passion at these school board meetings. But these young people saw them for years in the lead up to what we’re dealing with today.

Hagopian: Yeah, they did. And I think you’re totally right about the resolve of young people today. It’s just amazing to see how they use their platform as student athletes. My favorite part of the book is talking about the students from my class at Garfield High School. It was incredible to see their stories just come to life in the pages of your book and get to see the smiles on their faces when that section of the book got into Sports Illustrated and they were celebrated for their resistance after all they had been through — after the death threats that came streaming into Garfield High School for Jelani and Janelle taking knees at their football and softball teams, it was just a really important vindication of their work. So I just thank you very much for helping to lift those young people up, my own students, but also all of them across the country who deserve that recognition for their bravery.

Zirin: Thank you so much for saying that, and that’s wonderful to hear. Certainly one of the most rewarding things about the process has been hearing from students, the people I profiled saying to me, “Okay, you got the story. You got it right. Thank you for putting it together.” I would also just add though, Jesse, that you are one of the very low key heroes of the book because one of the common threads in the book is that the actions of teachers are really important in this process. So many of the people I interviewed, oftentimes the coach distanced themselves from the athlete, sometimes teammates distanced themselves, always the administration would distance themselves, but oftentimes it was the teacher giving them a pat on the back. The teacher.

My favorite story was the teacher with the student who felt so alone and so isolated. She did it with a friend of hers, she walked into her high school classroom, and the teacher yelled, “Hey, it’s Tommie Smith and John Carlos, everybody. Wow [clapping].” And that, of course, developed a thirst in her to read about Tommie Smith and John Carlos. And that was another common thread I saw, Jesse, that for a lot of these folks, Kaepernick was really their only example of athlete activism. Kaepernick’s great gift to them was this language of protest that they could do as athletes. Their inspiration might have been Trayvon Martin, but the person who gave them, who bequeathed to them, this language of protest as an athlete was Colin Kaepernick. And that, I think, is his great contribution to the struggle. What’s going to be remembered much more than his individual story is that method for doing what he did. I forget why I was going down that path in particular.

Hagopian: No, that was right where I was going, because you write about Rodney Axson Jr. who, I believe, was the first player to take a knee after Kaepernick, isn’t that right?

Zirin: Yes. And, just to say quickly, the place I was going is that people became like sports history mavens. These young people, all they knew was Kaepernick, but then all of a sudden, they’re reading about people like Althea Gibson and Billie Jean King and Eroseanna Robinson and Jackie Robinson and Ali and [Tommie] Smith and [John] Carlos — this whole world of history opened up to them that they just went through like sharks. Suddenly they’re reading something that feels relevant to their lives, and the arguments that they want to make when class is over.

Hagopian: No doubt. The students at Garfield who led that protest had been reading your work and seen your film Not Just a Game in my class. So that stuff is important, it gives them a whole other way to conceptualize their identity and understand what they’re doing as an athlete when they can see it as not disconnected from the rest of society.

Zirin: You mentioned Rodney Axson Jr. I was so taken with Rodney, it’s hard to chew, it’s hard. I’ve been sort of ducking and weaving around, telling my favorite stories from the book because they all mean a great deal to me. I hate the thought in my head of even prioritizing them because at the end of the day, this was young people just giving me a lot of trust, when they didn’t have to. I’m still convinced most of them talked to me just because it was the start of the pandemic and they were home and bored and had nothing else to do. Remember those first weeks of shut down, where there was just like done? I think they were like, “Oh, cool. Yeah, I’ll talk to this guy.” But, they trusted me. So I hate prioritizing them.

That being said, Rodney’s story in Brunswick, it has so much pathos to me, because he was growing up in Cleveland and his family moved to Brunswick precisely because they felt like their neighborhood in Cleveland had too much crime. They saw this path to the American Dream through the Brunswick suburbs, where they got better schools for the kids, less crime. But far from a better life, Rodney found himself an outcast at school, harassed by police. I mean, just not comfortable in his own skin. And what can possibly be worse than that? Especially for a young person to feel that way. To top it off, football was his outlet and he was good at it, but he also wasn’t starting. That just felt kind of sleazy and gross, because you just wouldn’t know. Is this because I’m one of the only Black kids on the entire team, because it certainly feels that way. But then his teammates start throwing around the n-word like it’s nothing, talking about opposing players. When he said to them, “You need to not do that,” their response was to say to him, “Well, we’re not talking about you, because you’re our teammate,” basically saying, you’re one of the good ones. And it broke his heart. When you couple that with the Black Lives Matter movement that was happening, he was like, “I need to do something.” But he’s not living in Ferguson, he’s not living in New York City, he’s not living in Seattle. He can’t just walk out in Brunswick and have a Black Lives Matter demonstration. But then when he saw Colin Kaepernick do what he did, it was like, bam, “That’s something I can do. That’s something I can definitely do.” And he did it.

Hagopian: I love how you write about how when he took a knee he said he wasn’t actually thinking about Kaepernick. You wrote, he said, quote, “I was actually thinking about my teacher, Mrs. Burgess. She was talking to us about the national anthem and about how the man who wrote the anthem actually owned slaves. I just love that the role of teachers and mentors showing up in your book is nurturing these youth.

Zirin: Also, isn’t that just a great example of the sort of thing that would make right-wingers, particularly in the state of Virginia, particularly in Loudoun County, just keel over. When I hear that, I’m like, “That’s what an educator is all about. That’s what it’s supposed to be. You’re trying to open eyes. You’re trying to teach the truth.” But if you’re on the other side of the aisle, you look at that story, you look at truth as something almost toxic, like opening up a lamp and having a genie come out or something. “Oh, no, look at you. You told them the truth about the anthem. And now Rodney, who was one of the good ones, is now taking a knee during the anthem. How dare you teach truth?!!”

Hagopian: The truth is dangerous.

Zirin: Poisonous. And that’s how they view it. I think that’s one of the great divides in this country right now, and it makes me wonder about us ever being able to come together. I mean, I view truth as the ultimate disinfectant, and they view truth as poison.

Hagopian: Yeah, absolutely. That’s the struggle so many of the educators in this room are in right now, just to say basic facts about U.S. history. I’ve got one more question for you before we move to breakout rooms. I’m excited to hear what comes from the breakout rooms and what conversations come up and how educators dig into this discussion and think about how they want to use sports more in their classrooms. But before we get there, I think sending us off with a conversation about how educators should teach about the history of sports. Why are sports such an important lens for analyzing society, and why have they been such a consistent site of social protests throughout U.S. history? And I was hoping you might also specifically tell the story of Eroseanna Robinson, the first athlete to refuse to stand for the anthem, and other athletes educators should know about to teach the intersection of sports and the Black Freedom Struggle.

Zirin: So just a small question, right [laughing]? This is what I think: I think sports is such a terrific lens because it’s the ultimate lens to tell the story about the United States of America. The reason for that is when sports began in this country as an organized business entity in the 19th century — and tell me if this doesn’t sound like America for a second — it was built on this basis, it’s built on the basis of the myth of inclusion and the reality of exclusion. The myth of inclusion and the reality of exclusion.

The myth of inclusion was how sports marketed itself from the very beginning, which is this idea of the level playing field, and anybody who’s good enough can do it. So if you can play, you’re taking the field. That was how they talked about it, and their little promotional films, like, “Hey, start playing this new sport called baskets ball! Get a peach basket and give it a try. Anybody who’s good enough can do it.” So, that was the myth of inclusion. But the reality, of course, was exclusion. If you were a woman, there was just nowhere for you to play. There’s no space for any sort of collective play. If you were Black or brown, it was like, “Well, if you want to form your own leagues over there, go ahead, but all the resources and attention and everything is going to be located on what we deem to be the American and national leads, which are going to be all white.”

But from the very beginning, the very beginning, there is an effort from the marginalized people to be included in sports. There is a fight to take the field. There is a fight to play. That, in and of itself, is like the story of this country, that there’s an image and there’s a reality and to try to make the reality even come close to the image it takes an absolutely relentless struggle to make that happen. So teaching about sports is teaching us about that struggle. So then, moving forward, if you teach about the Civil Rights Movement, the stories of Jackie Robinson, the 1960s, Muhammad Ali, the women’s movement, Billie Jean King, the story of LGBTQ liberation in this country, runs through the world of sports in so many ways. There’s so many resources that I could certainly recommend for folks, if they want to use stuff for the classroom. There’s a great compilation book called The Unlevel Playing Field, which I really recommend. There’s a great book about women in sports called Nike is a Goddess. There’s a terrific book that just came out this week, called Hail Mary: The Rise and Fall of the National Women’s Football League, about this story. Not a history I was aware of, but what a history to tell a story of: the 1970s and people feeling empowered and that reflecting itself in the world of sports. So, I strongly encourage people using sports.

And you mentioned Eroseanna Robinson. I mean, what a great way to show a picture or to start a class by showing a picture of Colin Kaepernick and feeling like he wasn’t the first person to do this. Because you’ve got the students’ attention. It’s like, well, who was the first person? Eroseanna Robinson, 1959 track and field athlete, refused to stand in opposition to spending that’s going on around the Cold War, the nuclear build up. Then that becomes another question like, well, what’s that about? The Cold War, the nuclear build up, what are you talking about?

Hagopian: A lens for teaching the Cold War, right?

Zirin: Yeah. You do it through the eyes of Eroseanna Robinson and the fact that she not only sat during the anthem, but she also ended up in prison and she had to go to the hospital for a hunger strike, because she was a tax resistor, precisely because of the money that was being spent on the Cold War. So, I love that story.

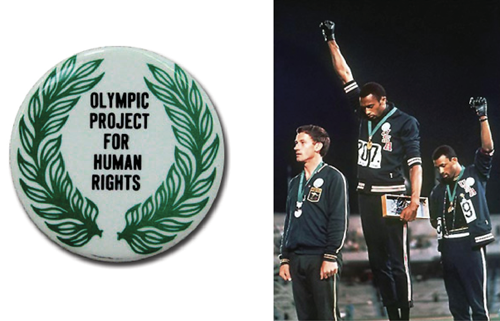

Then just one last thing, it’s like you show the picture of Tommie Smith and John Carlos, a lot of people know that moment from the 1968 Olympics. I mean, it’s on your shirt, Jesse. A lot of people know the moment, but it’s such a teaching tool because it was more than a moment, it was a movement, and to begin to talk to folks about what that movement was, the Olympic Project for Human Rights, what it stood for, the pressure it put on apartheid South Africa and the Olympics, the fact that they organized internationally, all of these things are just such great teaching tools. Then you can point at the picture and be like, “What do you notice other than the fists going up?” Then you can point out that Tommie and John aren’t wearing shoes to protest poverty, or that they’re wearing buttons that say Olympic Project for Human Rights, or that they’re wearing beads and scarves around their necks to showcase the history of lynching in the United States. So, it’s all of these interesting, incredible, what John Carlos calls artifacts, in the image that allow for just incredible discussions.

Hagopian: We would love to see if any other major questions come up. I have a couple more questions that we can start with, and then if any questions come up I can take a look at the chat box. I would just like to hear from you, Dave, more about how you came to focus on sports as a way to analyze society. I think telling us about your story and how you became a political sports writer would be interesting to the educators here.

Zirin: Well, sure, I’ll keep it brief. I mean, basically, I was really into politics and movements when I was in high school. In college, I was studying them and I had this whole parallel life where I was a sports obsessive, and I played sports in high school, and I was super into it, but it was sort of in its own realm. And that really changed for me when a basketball player for the Denver Nuggets named Mahmoud Abdul-Rauf made the decision to not come out for the national anthem. All of a sudden sports was a political issue, and there were politics and sports and it was on Sports Center. I know there’s a whole history of this, we were talking about it before. But to me this history didn’t exist. I didn’t know this history. I had no idea. I thought I knew everything about sports, but I realized all I really knew were batting averages and not necessarily the way people’s struggles would enter the world of sports. That became a kind of mini obsession. I didn’t have Google, I couldn’t just say “sports activists” and see what came up. I had to dig, I had to do research, not only microfilm but microfiche, and just tried to read and learn as much as possible about athletes who had been political. And that’s really where it started for me.

What help me a lot was a professor at Macalester College, Professor Mahmoud El-Kati. Professor Mahmoud El-Kati was somebody who taught a class called the Black Athletes Since World War Two. I couldn’t get into the class, but this was where my obsession was. My roommate was in the class, so I just read his books and would sneak into the classroom. I mean, I read more for that class than I did for my own classes. And that’s really how it started for me.

Then I was really into the idea of being a political sports writer, or writing about the politics of sports, because when I started, when I was doing my microfilm and microfiche digging, I saw there was an amazing history in the Black press, in the Chicago Defender, the Amsterdam News, the Baltimore Afro-American with Sam Lacy, certainly, the Pittsburgh Courier definitely had amazing political sports writing that took racism on. I also learned a lot about Lester Rodney, who was the sports editor for the Communist Party’s newspaper in the 1930s, and fought for the integration of baseball. Then I got to meet Lester Rodney, who was in his 90s, and talked to him about what I wanted to do. I said, “I want to be a political sports writer like you,” and Lester looked at me and he said, “To be 80 again.” It was very funny. And since that’s really what it came out of, it came out of both an anger at having history hidden from me, but also a feeling of responsibility to carry on a tradition.

Hagopian: Yeah. That’s wonderful. I’m seeing some great stuff in the chat that I want to lift up. First of all, if any of you have had students participate in these protests, we’d love to hear about that. So, if you want to drop in the chat what happened at your school around the Kaepernick effect we would love to hear that. There have been some good questions as well. JT says, “Dave, what do you see as the WNBA role in the 2020 election and the activism possibly ahead of the NBA?”

Zirin: Oh, definitely. First and foremost, yeah, the WNBA has been on the front lines every step of the way, predating the Black Lives Matter movement around issues like reproductive rights, certainly women’s rights. They’ve been, I think, more than any other sports league, a political weathervane for everything we’re doing right now and everything we’re seeing. Even protesting during the anthem, Colin Kaepernick was the first person to take that knee in the recent period, but it was basketball players on teams like the Minnesota Lynx who were not bowing their heads, wearing political t-shirts, and holding hands during the anthem, which was in itself a step in that direction of saying, “Hey, the anthem is actually a political space. It is a political space. It’s not this neutral space. It’s political.” And it was the WNBA athletes who first stepped in that direction.

Also, yeah, the Senate. I mean, I have serious problems with what the Democratic Party is doing with this, but the Senate would not be in Democratic Party hands without the WNBA. Simple as that. The work that they did in Georgia to elect Raphael Warnock was essential, and Reverend Warnock, Senator Warnock, says that and it’s acknowledged. I mean, it’s going to be taught in political science classes, what these WNBA athletes did. What they did that was particularly brave and historic was that it wasn’t just them saying, “We think Raphael Warnock would be a better senator than this Kelly Loeffler person.” It’s that Kelly Loeffler owns 49% of the Atlanta Dream, a WNBA team, and Kelly Loeffler was running for office by using the fact that WNBA players were being political, like they were her own specialized team of Willie Horton’s that she could point at and say they’re part of the problem. They’re part of the problem. And one of her players said, “Well, how about we meet and talk about it.” And she refused to meet with that player, refused to meet with her. So they decided, “Alright, well, you don’t want to talk to us, you’re going to demonize us for the purposes of running for office and kissing up to the klan community of Georgia,” which she did. I’m not speaking just extemporaneously about that. They changed Rafael Warnock’s and the entire perspective of his campaign. He was only polling at 9% when they decided to support him, and they turned him into this national candidate because it was too delicious a story, like they’re taking on the person who actually has control over their lives and they’re sitting there basically saying, “No, no, we’re actually going to force you out.” So it’s a story not just about mainstream politics, it’s a story also about labor, it’s a story about how different women can have different objectives politically in a given moment or situation based on whether they’re on the floor or in the big box. It’s a story that I think resonates with students, especially because one of the people on our team who wanted to meet with her was eventually part of a group that actually bought her out and kicked her out of the league. And when does that ever happen?

Hagopian: Yeah, that’s an amazing story. There are so many good questions popping up. I’m curious about this, too, Martha said, “Any Kaepernick effect examples from outside the U.S., especially since you’re in Barcelona right now?”

Zirin: Oh, tons. I mean, it’s taken European soccer by storm, Australia and New Zealand. The interesting thing out here is that, first of all, they don’t play the anthem before sporting events. That’s a lovely U.S. contribution to world sporting culture. They often don’t except in very, very particular circumstances. But you do have — like in the English Premier League and some of the other soccer leagues — players taking a knee before the game. For a while I thought that that was a kind of whatever thing because it’s being done with the approval of management, it’s being done as a team activity. It’s obviously not being done during the raising of any kind of flag. So, all they’re really doing is taking a knee as a group to basically say, “We don’t like racism.” So I thought, “Okay, that’s a little different than what we’re seeing in the States.” But then I had a reporter from one of the Irish papers who was interviewing me, and he gave me a real history lesson that I needed to hear about just the incredibly virulent history of racism in European soccer, and about how there are very racist fan clubs, and there are also very antiracist fan clubs. So to have players take a knee, it is like them saying to their fans in a very, very upfront way, we side with some of you, but not all of you. And that’s important, that matters.

Hagopian: I like that. That’s really cool. Well, there’s a lot of teachers here that had student protests. Sherry and Carolyn had some really cool stories here about their all girls high school joining the struggle. Excellent. There’s an interesting question about how do you talk to students about moving from the protests to real action? I’m losing it in the chat right now. Shoot, I wish I could read it out word for word. There are so many great comments here. I’m losing it. But I think it’s an important thing to grapple with — What next after the knee? How do you talk to students about that?

Zirin: Yeah, how to talk to them about what they do afterwards. What’s the next step? I mean, that was a question I was asked earlier today, actually. I mean, Jesse, I think you’re better equipped to answer this than I am. I just think the starting point is asking them what they want to see and then helping to facilitate their own vision. As you know, some of the people I’ve talked to, what they wanted was an assembly where they could actually raise all the micro and macro aggressions that they deal with at school. Then they fought for that assembly, and they actually won it. You know, that could be something, it could be a change in the way that the sports teams operate. Maybe that’s what they want to see. It could be that they want the school senate to issue a statement about getting police officers out of their school. I mean, there are all kinds of issues that can come up from something like this. But I think it’s about helping them articulate their own vision, and then working with them on how to put it into practice. Because if somebody’s taking a knee, there’s a demand in there. You know the old expression, “Power concedes nothing without a demand?” There’s a demand in that knee, and so helping them articulate what that is, I think, is really important.

Hagopian: I totally agree. I mean, at Garfield, when our football team became the first in the nation to have the entire team take a knee, they didn’t just take the knee — which I think is really important in and of itself. I think sometimes adults can gloss over that, and say, ”Oh, all you did was take a knee. But what are you really about? What did you do next?” I think, just pause for a moment and honor the bravery of that. That they had the courage to call out this country when so many others don’t I think is important. But then the football team also said that ethnic studies was something that all students deserve to have access to, and helped organize the struggle for Black studies and ethnic studies. And we won Black studies and ethnic studies in the Seattle Public Schools. You also can’t tell that story without acknowledging the role of the youth and the student activists. So, just a couple more questions, because we have some great ones in here. “How do you encourage activism in athletes who have been shown the repercussions of speaking their minds are greater because of who they are, and sometimes don’t provide enough benefit to outweigh the risk?”

Zirin: That’s a great question, too. I couldn’t tell if the question was assuming that they had looked at the book and were seeing that level of backlash, or if it was something maybe they just intuited themselves, that they would receive a lot of backlash? So, I guess it has to do with them reading the book first, I think the book is not starry eyed. I mean, it’s very real in terms of what you have to confront and deal with. I think young people appreciate that. I mean, it’s honest.. This is what you’re going to have to deal with, and these young people, though, in the book, they say it was still worth doing. So, just keep all that in mind before you go ahead — go in with eyes wide open.

Also, there’s pre work you can do as well, which I think the book at least helps [with]. Like, what do we know from the book? We know that it’s always easier if you can get some teammates to do it with you, because you can share the weight of the backlash. We know that it makes a huge difference if your coach has your back. But really think about that critically — do you know your coach? What will your coach say? And if you think your coach would have your back, talk to them about it. There are little things that can actually make it easier. Another big one, another case more recently, is to see if you can build support in the school and have people taking a knee in solidarity with you in the stance, which is another thing that makes a big difference, because then that becomes part of the story. It becomes more difficult to write off people as being like a lone malcontent or something. Because that’s what they’re going to try to do, they’re going to use mockery and isolation. But if you counter that with numbers, and with people power, it destroys their narrative.

Hagopian: Yeah, no doubt. I love all these stories of resistance that are dropping in the chat. Anna said, “It wasn’t just the athletes who took a knee. It was also the musicians.” The choir, the marching bands.

Zirin: Someone with a bassoon took a knee.

Hagopian: Yeah, I love that even sometimes some of the people who are doing the singing of the national anthem [take a knee].

Zirin: I interviewed someone, her name is Leah Tysse. She was singing the national anthem at a Sacramento Kings NBA game and took a knee.

Hagopian: Yeah, that’s wonderful. Then you have the opposite side: Jim talks about in his high school that the head football coach said they wouldn’t play if they took a knee. So, instances of the coaches and mentors also cutting down the students.

Zirin: The last thing you want is for a student to educate themselves and actually try to do something with that education [smirk].

Hagopian: So many great stories, maybe just add on one, one last question. I think just the last year and a half has been such a watershed moment in U.S. history in many ways — with the uprising, dealing with COVID-19. How do you think that this movement and the activism of 2020 will be written into the history books? How will future generations look back at this time that we’re in right now?

Zirin: Well, it’s interesting. There’s that expression, “history is written by the winners.” So, how will 2020 be remembered? It’ll depend on whether this generation is able to win. If they’re able to win an antiracist future, then both the kneeling part of this history will be remembered, Black Lives Matter will be remembered, and the fact that 2020 saw the largest protests in history will be remembered. It will be part of a narrative about how this country finally faced its past and its present in order to change its future. Now, if the people of Loudoun County win then we know how it’s going to be remembered: 2020 will be about what they said in the 60s, they’ll say it’s about lawlessness. The people who took a knee, they’re going to be forgotten. Colin Kaepernick, maybe there’ll be a picture of him in a Texas history book, but it’ll be one of those pictures without a caption. And the student will say, “Can you tell me who this football player is? We love football in Texas. Who is this guy?” And the teacher will say, “I’d love to tell you, but I’m not allowed.” That’s the other future.

Hagopian: Yeah, well, the people in this meeting tonight have a lot to say about which future we end up having. Encouraging your youth to participate in this uprising, teaching the truth, all these things can help us achieve that much better picture that you painted first. So, Dave, thank you so much for staying up late with us. I’m looking forward to hearing about your trip at a later date. What an incredible conversation and I think this will be so important for so many of the educators with us.

We want everybody to fill out an evaluation form. So, please don’t drop off until you have filled that out. I just want to also recommend some of your other books, especially the YA version of Things That Make White People Uncomfortable. Everybody should pick that up and pair that with the Kaepernick Effect in your classroom. Wow, look at all the love in the chat. Why don’t we unmute real quick and everybody give a shout out to Dave. We appreciate you being with us.

While this transcript was edited, there may be minor errors or typos — if you notice something you believe to be incorrect please contact us at zep@zinnedproject.org.

Audio

Listen to the recording of the session on these additional platforms.

Sparked by this discussion with Zirin, some participants in the class shared similar stories of student activism in their own communities:

After I taught my 8th grade civics students a lesson on Kaepernick, the anthem, and the 1968 Olympics, one of my students started taking a knee and putting his fist up every day during the pledge of allegiance. Other students were surprised to know that they could not be required to stand for the pledge. I kept a copy of the West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette case from the 1940s about free speech and the pledge in my drawer to use if (and when) students were challenged for not standing. — Billy Rutherford, Boston, Massachusetts

The Kaepernick Effect impacted students at the Catholic all-girls high school I was at when an in-league school six blocks away from us modeled walk-outs and football game protests. The proximity and influence was stifled by local admins. — Carolyn Sideco, San Francisco, California

We had a student led protest after the murder of George Floyd, and a group of teachers followed the students with the support of our administration. We took a knee for nine minutes, and my colleague raised his fist during this time period. Around the seven minute mark, his arm started to shake, and he asked me if I had him and could hold him up. I braced my arm to hold him up, without question. He is a football coach and educator at my school. — Vikki Reid, LaGrange, Illinois

I teach at an all girls’ school and our cheerleaders created a cheer where they end with their fists in the air. The place went crazy and the girls won great admiration from the fans. — Nelva Williamson, Houston, Texas

We had both athletes and musicians participate. . . some athletes took a knee but, in addition, our choir typically sings the national anthem before games. . . we had multiple students take a knee and refuse to sing. No punishment or consequence as the choir director was supportive. — Anna Schottenstein, Bexley, Ohio

We had marching band members who took a knee while they were playing the National Anthem at football games. We also had members of our student body who protested via a walk out, advocating for a safe and secure environment for all at our school. . . . During the spring of 2021, our social justice club hosted a social justice rally on the football field, advocating for justice for all students. As part of our high school teachers book study of The Guide for White Woman Who Teach Black Boys, we came up with an action plan, in collaboration with our students of color. We asked what they would like to see and what it would look like and sound like. In addition, administration and staff met with our social justice club and interested students to find out what they felt the issues related to equity and diversity were at Linn-Mar HS and the students made a list of suggestions and we are working through them, including SLOW changes in the curriculum. First up a new diverse literature course will be offered next year. – Sheri Crandall, Linn-Mar HS, Iowa

Baltimore School for the Arts led a protest from their school down to the school district. Once there, they addressed superintendent, performed poetry and song written for the moment in early pandemic, and then made demands about the curriculum they need to be evaluated upon, saying The Autobiography of Malcolm X, for example, must be taught. The superintendent listened and references that demonstration . . . so do I! Go students! — Kelly Barnes, Baltimore, Maryland

The football team of Garfield High School in Seattle taking a knee during the playing of the national anthem.

Resources

Here are many of the books, articles, films, and more recommended by the presenters and also by participants.

Related Books

|

|

In addition to The Kaepernick Effect: Taking a Knee, Changing the World, the following books were referenced. A People’s History of Sports in the United States by Dave Zirin (The New Press) Full Dissidence: Notes from an Uneven Playing Field by Howard Bryant (Beacon Press) Hope for Haiti by Jesse Joshua Watson (Penguin Putnam Trade) Step Up to the Plate, Maria Singh by Uma Krishnaswami (Tu Books) The John Carlos Story: The Sports Moment That Changed the World by John Carlos and Dave Zirin (Haymarket Books) The Revolt of the Black Athlete by Harry Edwards (University of Illinois Press) Things That Make White People Uncomfortable (Adapted for Young Adults) by Michael Bennett and Dave Zirin (Haymarket Books) Tigerbelle: The Wyomia Tyus Story by Elizabeth Terzakis and Wyomia Tyus (The Edge of Sports). Wilma Unlimited: How Wilma Rudolph Became the World’s Fastest Woman by Kathleen Krull (Clarion Books). |

Articles

Films

|

Colin in Black and White by Ava DuVernay and Colin Kaepernick Walkout by Moctesuma Esparza

|

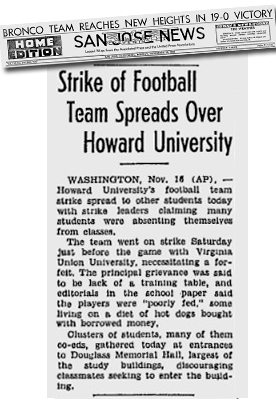

This Day In History

Participant Reflections

What was the most important thing (story, idea) you learned today?

It is not easy to choose one. I am inspired by the students who are taking action and the teachers/adults who support them by teaching the truth and sharing examples from history. I have coached and seen sports as a part of social protest, but I have new resources and more information on the intersection of sports and the struggle for inclusion and liberation.

A sketch of the history of athletes’ activism for equity in the U.S. going back many decades, with examples that are not the big, famous ones that everyone hears about and instead include women and names that are not known in every household.

Underscoring that the big name stars might make the history books, but it’s the individuals in the masses that truly pushed a moment into a movement. Let’s find, memorialize, and share those narratives!

The moment we all remember is NOT the most important thing. What folks did afterwards is what really matters. Movement > moment.

The importance of collectivism. . . encouraging students to work together to fight the wrongs in our communities.

That I am not alone. That the kids are alright. I am so inspired by Dave’s work documenting this important history of the brave choices of our student athletes all over the country.

The important role of teachers, coaches and administrators in encouraging young people to “change history” — it takes only a word or two to signal support and respect for young people’s resistance.

I was taken by the statement that Dave said about Tommie Smith talking about the number of fists that were raised after the 1968 Olympics — it makes sense, but I never really thought that much about it before. Considering the way that Kaepernick has impacted so many people, it makes me want to look into how Tommie Smith and John Carlos influenced protest in young people.

They don’t play the anthem before sporting events in other countries, but you do have players taking a knee before the game. Zirin paused to emphasize the context for European sports, which are especially racist. Taking a knee in that context means that the players side with some of the fans, but not all of them, which is significant.

How Trayvon Martin was a catalyst for this generation like Emmett Till was for young civil rights activists in the 1950s and 1960s, but that athlete activists provided models of what to do with that anger.

The importance of uplifting our youth and teaching our youth the ways in which their voices and actions have always been central to the Black Freedom Struggle.

What will you do with what you learned?

I will invite more students to attend with me, provide service learning credits, and continue to connect modern world history and 20th century U.S. history to the events of our day with pre-vetted #TeachTruth folks, such as Dave Zirin.

Support teachers and students to research athletes and sports protest/history.

Think more about how I can support student activism at my school with athletes or non-athletes. Also, how I bring stories of sports into the ELA classroom that offer connections to activism.

Continue to share the ZEP lessons and resources and all the info I gather from reviewing the resources and reading the texts that I have been given.

Take it back to my T4BL study group.

Make my classroom a place of radical confirmation.

I want to bring more sports activism in our research papers — at a 4th grade level.

Incorporate the reading suggestions and historical figures into my Sociology of Sport class (and hopefully other classes too!)

I am currently working with a local coach on modifying a toolkit for sports coaches around integrating SEL into their practice- and one of our top priorities is integrating equity and activism. I am excited to think about how to include what I have learned here into that work.

Continue to use stories of sports in teaching and add more stories of female athletes and their powerful role in making movements.

I will be looking more into Dave’s book and the Zinn Ed Project!

Additional Comments

Thank you for the work you do — it is important to connect and learn from people across the country doing this work. It can feel isolating and lonely and hard. Opportunities like this remind me that I am in this with MANY others. Dave — I have a few of your books and will definitely be getting this one. It was incredible to be “in” the same room as you! Thank you for telling the stories that need to be heard and known.

Thank you very much for such an amazing session, which gives me hope about our shared future.

I loved everything about this workshop. I was especially touched and elated to know that it was accessible to those who communicate via ASL. The provision of skilled interpreters, subtitles, and available transcript was absolutely phenomenal and literally OUTSTANDING. It’s unfortunate that those who are DEAF and interested in participating in any kind of workshop, be it in person or via online, have to miss out due to lack of inclusion and accessibility. Kudos to ZEP for taking measures to ensure that people like me could participate and have FULL ACCESS to everything afforded to others.

Presenters

Jesse Hagopian teaches Ethnic Studies and is the co-adviser to the Black Student Union at Garfield High School in Seattle. He is an editor for Rethinking Schools, the co-editor of Teaching for Black Lives, and editor of More Than a Score: The New Uprising Against High-Stakes Testing.

Dave Zirin, The Nation’s sports editor, is one of UTNE Reader’s “50 Visionaries Who Are Changing Our World” and is the author of ten books (including A People’s History of Sports in the United States) on the politics of sports — none more important than The Kaepernick Effect for helping educators understand how young people can change the world.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn