On January 13, Teaching for Black Lives co-editor Jesse Hagopian and Rethinking Schools executive director Cierra Kaler-Jones discussed Hagopian’s latest book, Teach Truth: The Struggle for Antiracist Education, and the campaign to fight back against bans on books and education.

In the excerpt below, Hagopian explains how today’s book bans and attacks on educators are divide-and-conquer tactics used by the right during the McCarthy era to silence movements for justice and suppress the crucial lessons of history.

I love the idea of “organized remembering” and appreciate the naming of the “violence of organized forgetting.” Things don’t happen by accident and we have to be as purposeful in the truth telling as others are organized in trying to suppress it.

A beautiful reminder that what happened historically is a necessary part of teaching about what’s happening now.

I love the focus on educational arson. It’s so important to see what the authority figures are scared of. This is the important knowledge that people need.

Jesse said, “They don’t burn books because they fear the past, they burn them because they fear the future they could inspire.”

Teaching truth is a work of resistance that we must never grow weary of.

Epistemicide was an eye-opener to me. White supremacy is very intentional about intellectual violence.

This class, and Jesse’s new book, powerfully reveal that the fight for antiracist education is not just about curriculum, but about confronting systemic inequities woven into the very fabric of our educational system, demanding a courageous reimagining of how we teach and learn.

Event Recording

Transcript

Click below for the full transcript with resources mentioned in the discussion.

Transcript

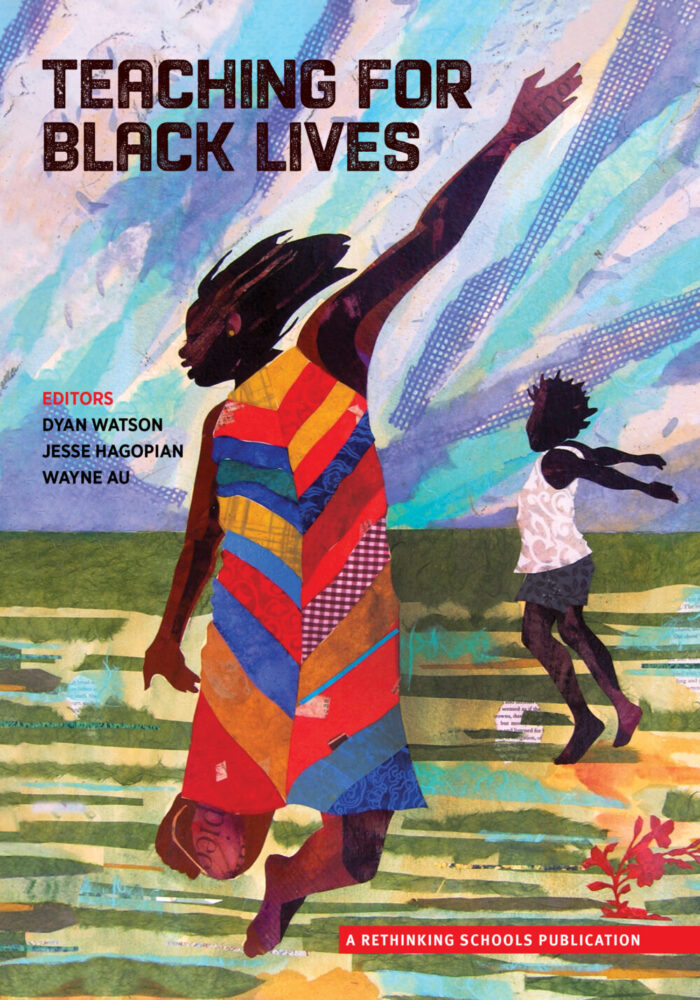

Cierra Kaler-Jones (she/her): We are about to begin our conversation with Jesse Hagopian. I have Jesse’s official bio, but I just wanted to say, from a very personal place, that tonight is a very special night for many reasons. Jesse’s book comes out tomorrow, Teach Truth. So you all are actually getting a sneak preview of the book. This is actually Jesse’s first public conversation about Teach Truth. It’s so exciting that you all get a sneak peek. I also wanted to say that, in addition to being a brilliant organizer and radical, thoughtful educator, Jesse is also a really wonderful friend. He’s always the first to affirm you, laugh with you, and talk with you for hours about collective dreams for liberation. I’m so grateful to have a friend like Jesse in the struggle. Jesse, you have taught me so much about being a storyteller, about creating time for rest, and what it means to teach truth in the classroom, and also beyond. I’m so, so excited that folks will get to learn from you as much as I have. Now, I’m happy to welcome Teaching for Black Lives co-editor, Jesse Hagopian. He is an editor for Rethinking Schools and campaign director for the Zinn Education Project. He joins us today to discuss his latest book—look at it, it’s beautiful, it’s fantastic—Teach truth:The Struggle for Antiracist Education and the campaign to fight back against bans on books and education. Jesse, I’m so excited.

Jesse Hagopian (he/him): I’m so excited for this conversation, and I don’t think I’ve ever had a better introduction. I really appreciate not just this conversation tonight, but all the work that we’ve gotten to do together, and all the play, and just hanging out as well. And I look forward to many more years in the struggle with you. So thank you so much, Cierra.

Kaler-Jones: Thank you. I appreciate you. Now, speaking of you being one of my favorite storytellers, you begin the book with a personal and a powerful narrative about your family’s discovery about your ancestors. So, can you share a bit more with us about your family’s story? How does it shape your commitment to education and being a truth teacher?

Hagopian: Yes, thank you for starting the conversation out with my ancestors, because that’s really how I start the book off. In fact, I thought I’d just read folks the dedication. I wrote in the dedication for my ancestors:

Writing this book has allowed me to delve into the portal of history and draw nearer to you. I am grateful to be closer to you now than ever before, and grateful for all you have taught me. No one has the right to tear us apart by erasing your legacy. My supreme aspiration is to guard your memory and make you proud.

As I began writing this book in the summer of 2021, my dad made a stunning discovery. He found out which plantation our family had been enslaved on, and I opened the book with the story of my family’s journey to discover the plantation in Mississippi where our ancestors were enslaved. That journey was delayed multiple times by COVID, long Covid, [and] my dad’s stroke, but we eventually stood on the land where our ancestors toiled under unspeakable conditions. I was there at the burial ground for our enslaved ancestors, and I wrote a letter to them that we read aloud as part of our ceremony to honor our ancestors. So, I thought I’d just read the very end of that letter that I read aloud at the burial site. I conclude the letter to my ancestors saying:

We are here to experience a truth deeper than any that can be understood intellectually. We are here to make a promise to you, to this land, and to each other. You will not be forgotten. It doesn’t matter if they pass laws that make it illegal to speak of you, teach about you, or learn about you, because those laws don’t govern us. Only truth and love govern us, and so we will pass on the knowledge of this land and your existence here to our posterity, and to all who we encounter. We send to you our deepest gratitude for gifting us the will to survive and the spirit of resistance that you passed on to us through your blood and through your stories. With eternal love, Jesse, Jomana, and Gerald (my dad).

After reading that letter we knelt on the ground to be closer to our ancestors. It was just one of the most important moments in my life, and I think something that will sustain me until my last breath in pursuing that promise to my ancestors to teach the truth. I see teaching the truth about my ancestors as both an act of remembrance and an act of rebellion against a system that would rather have us forget what happened in this country.

Kaler-Jones: Oh, yes, thank you so much. And thank you for sharing your words directly from the book. It’s just so moving to hear your story, your experience, and to be on that land, to reclaim those stories, and to be able to pass those stories on. Wow!

Now you talked about it being an act of rebellion. Right now, in 44 states and counting, legislation has either been introduced or passed that denies educators from teaching the truth about history, creating a chilling effect, and the termination and doxing of a lot of teachers which you interviewed in your book. What are some of the root causes of the attacks on education that we are experiencing now, and why is the right latching on to the term critical race theory?

Hagopian: Yes, they certainly are, aren’t they? The right has latched on to critical race theory as this catch-all term to weaponize it against everything they fear. This is part of what I describe in the book as post-truth schooling. This is an effort to rewrite history to justify the current inequalities that exist. The attacks on education are really just so over the top, so absurd today, that I think only really the Onion can capture what’s going on in society right now. If people remember the Onion headline that ran above the picture of a Black teacher, it said: Teacher Fired For Breaking State’s Critical Race Theory Laws After Telling Students She’s Black. It’s as ridiculous as the Onion headline is.

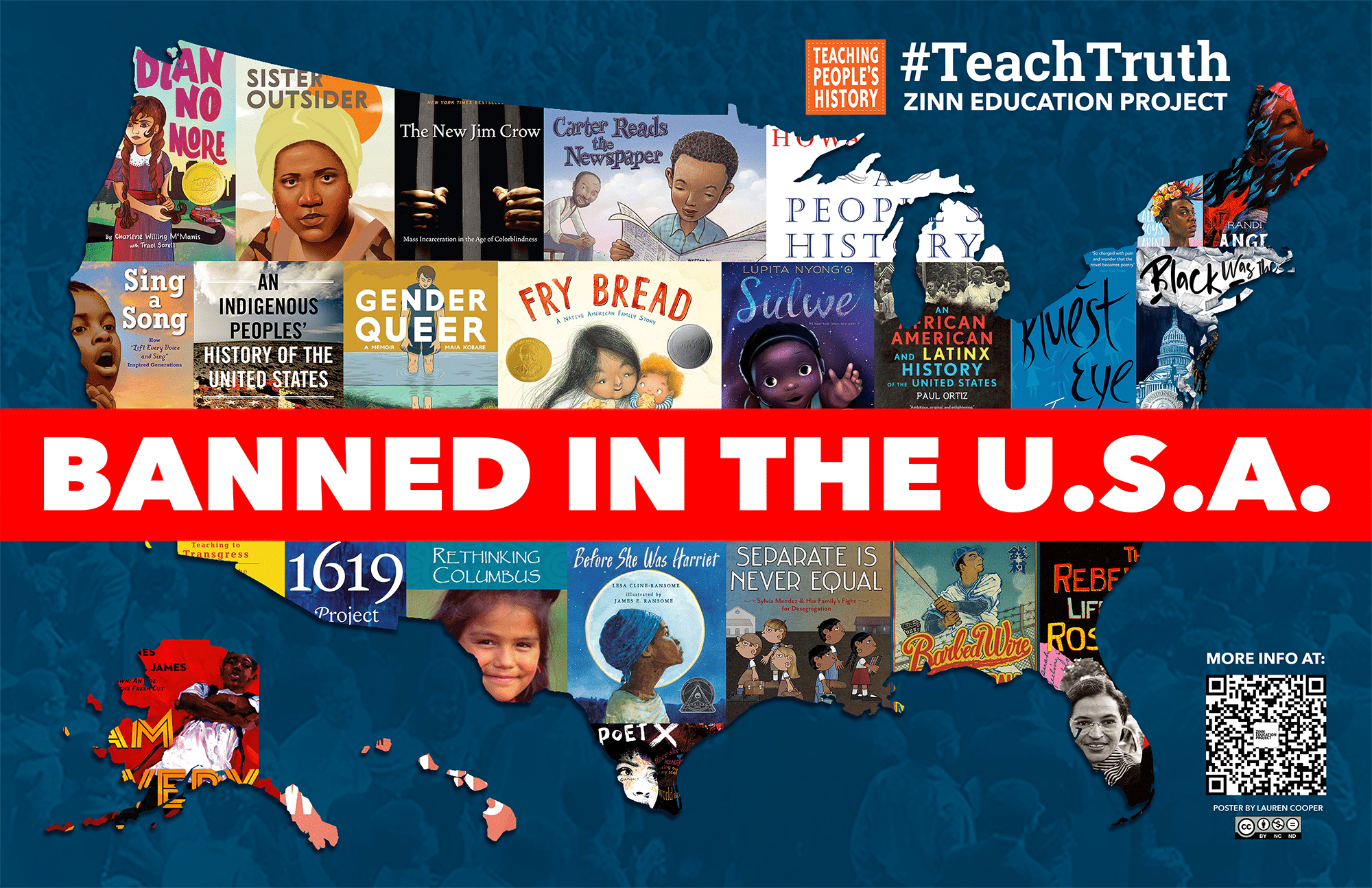

The reality of the laws that are being passed are more ridiculous. You have to consider the laws in Florida. Under the current law in Florida, Florida’s official state curriculum declares that slavery was quote “of personal benefit” to Black people. For real. This isn’t in the Ku Klux Klan’s youth handbook, this is in the state mandated curriculum that calls slavery “of personal benefit” to Black people. They banned AP African American studies class, and it is now a felony in Florida—if you get caught with a banned book in your classroom you can go to jail for 5 years. If you get caught with a book that tells the truth about Black history, or about gender identity.

And the problem isn’t just in the South or in red states. Many of you educators here today know this. In New Hampshire they proposed making educators sign a loyalty oath similar to the one that they made educators sign during the Red Scare. These anti-truth laws have passed in Idaho and Montana and Iowa. And it’s not just the statewide bans. In California, these bills have been passed in at least 7 districts. In the state of California over 110,000 students go to school where it’s illegal to teach the truth. We’re now in a situation where almost half of all public school children across the country today are subjected to laws that require educators to lie to their students about systemic racism, and many laws also require dishonesty about gender identity and sexuality.

In the book I call these laws “truth crime laws” because they criminalize educators’ ability to teach honestly about history. These truth crime laws are really grounded in fear, and I call the people that perpetuate these laws, I call them in the book, “uncritical race theorists.” Today the conversation about critical race theory is ubiquitous. But I think what’s not really discussed—and what needs to be at the center of the debate about education—is uncritical race theory. This is the set of ideas that unquestioningly reinforce existing racial power relations, unequal power relations. Uncritical race theory [is a] system of ideas that deny that racism exists at all, or maintains that racism primarily victimizes white people, or rejects any idea of systemic racism instead for ideas around individual bias. Uncritical race theorists position themselves as neutral and objective—just natural ideas—but in fact, they have a highly developed idea of race, and they have tried to politicize the classroom to an extreme extent.

One of the best examples of uncritical race theory I could give you comes from our president-elect, who in a speech in June 2024, at the Faith and Freedom Coalition, was criticizing proposals to change names of schools. I wonder if people saw this speech. He said, quote, “How about George Washington High School? They want the name removed from that school, but they don’t know why. You know, they thought he had slaves. Actually, I think he probably didn’t.” And there you have it, the greatest example of uncritical race theory. They would just rather lie to youth about American history than confront the uncomfortable truth, the cotton picking truth, that George Washington owned 123 enslaved Black people and added 153 more enslaved Black people through marriage. Trump believes that dishonesty about us.

History is essential because if students understood this country’s foundation in genocide and in enslavement they might question today’s unequal distribution of power. That’s why, when I teach George Washington, I don’t just teach about his policies and his power. I also teach from the perspective of Ona Judge, who was an enslaved Black woman who bravely escaped a forced labor camp. I want my kids to think critically about our history. I want them to refuse to exclude the role of race in U.S. history as their part of that inquiry.

In the book I traced the history of uncritical race theory, law, thought, and truth crime laws from the first anti-literacy law in South Carolina in 1740, banning Black people’s right to to read and write all the way up through today’s attack on critical race theory. I hope people will dig into that to see that people like Trump and Christopher Rufo, their legacy is one of the anti-literacy laws and the attacks on Black education, all through history. Our legacy is one of those who built the pit schools and the hush harbors—secretly, clandestinely educating Black people about their history in order to resist. I’ll just end by saying that I think we have to build a new movement for racial justice that not only uplifts the popular slogan of the Black Lives Matter movement, that says Legalize Being Black. We definitely have to fight for that, but to achieve that, I think we also have to couple that demand with the demand to legalize Black history if Black lives are ever to be truly valued.

Kaler-Jones: Yes, wow! I have my Legalize Black History shirt on for Jesse today. Perfect segue. For everyone who’s listening in, I highly recommend diving into the Teach Truth book, because Jesse just catalogs this history so thoughtfully and strategically, weaving so many historical moments together that, when you read it, I mean, my mind was just blown, of the connections and the history that they’re trying to ban to make it so that we can’t learn that history and make connections to today. Jesse, you make connections not only between what’s happened historically and what’s happening right now, but also between the attacks on teaching the truth about racism, the anti-LGBTQ+ plus legislation, and the backlash that a lot of educators are experiencing when teaching about Palestine and Israel. So, can you share the connections between these struggles for justice and why uncritical race theorists are attempting to police students and teachers?

Hagopian: Yes. I just love that we’re having this conversation. It’s amazing, after all these years of us interviewing everyone, that we get to dive into it. I thank you for the close read you did of the book and the opportunity to share some of these connections, because I think all these attacks share a common playbook, the playbook of divide and conquer, the playbook of McCarthyism. Whether it’s banning books on race or silencing LGBTQ+ voices or suppressing critiques of Israel’s policies, I think the goal remains the same—to pit people against each other, to suppress marginalized voices, and to preserve the current power system. Teaching about the intersections of race, class, gender, imperialism, I think this really threatens their agenda because it equips students with the tools to recognize and challenge oppression.

They claim that critical race theory is divisive, but I think what’s divisive is racism, xenophobia, homophobia, transphobia. Those are the tactics of divide and conquer. Today’s uncritical race theorists are just recycling strategies from the McCarthy era. They’re borrowing from the Red Scare and the Lavender Scare to attack honest educators and movements for social justice. During the Red Scare, teachers who encouraged students to question inequality were labeled as Communists and they were fired by the thousands all over the country. As I said, they had to sign loyalty oaths. There were book bans. Over 400 teachers in New York City alone were fired during the Red Scare, and the Lavender Scare also had a devastating impact. I think even more people were fired from the federal government under suspicion of being homosexual than even were fired under suspicion of being Communist. And this is what we’re seeing today. The Don’t Say Gay laws, Don’t Say Trans laws are echoing the Lavender Scare bigotry that we saw in that era.

Red Scare tactics are certainly being applied today to educators who are teaching the truth about the genocide being perpetrated by Israel in Gaza. Many politicians, both Republican and Democrat, expressed more outrage over students protesting and camping out against the genocide than they did when Israel was bombing Palestinians in their tents in refugee camps. These attacks are not about protecting education, I think they’re really about silencing solidarity, silencing movements for justice.

I’ll just end by saying, you know what really ended the McCarthy era, what broke through the paranoia and the hysteria of the Red Scare and Lavender Scare? It was the Civil Rights Movement. It was the great resurgence of the Black Freedom Struggle that then gave birth to a student rights movement, a women’s rights movement, and an anti-war movement that swept campuses to put an end to the murderous war in Vietnam. This incredible struggle freed people from the fear of being labeled Communists to actually look at how we are going to build a society that is built around meeting human needs and not just enriching the few. And they don’t want us to learn that history, because then we would begin using those lessons to build a new uprising, to wipe away their lives today.

Kaler-Jones: Yes, yes, yes. We’re actually going to talk more about that later on, we’ll talk about the resistance to the truth crime laws. But one of the other things you talk about is the silencing and the erasure. So, I want to talk a little bit more about how in the book you talk about educational arson. So you’re talking about erasure and violence as a means for uncritical race theorists to engage in this erasure of information and knowledge. What is the purpose of educational arson, and what are some historical and current examples of how that happens?

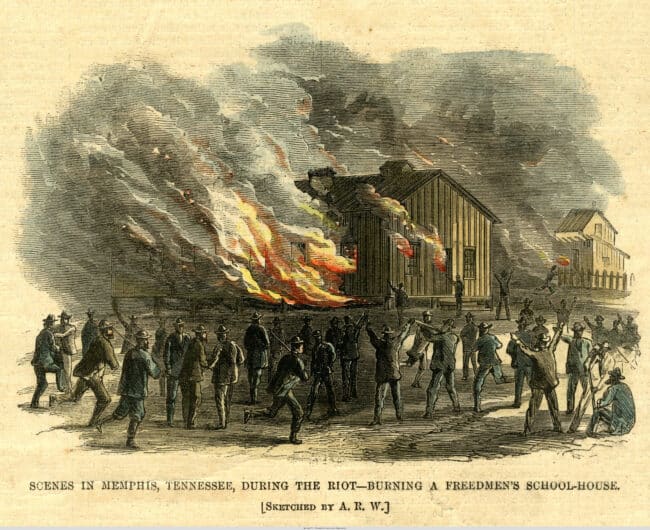

Hagopian: The more I researched the history of Black education, the more I noticed this pattern of white supremacists using flame, using gasoline, actually physically burning books and schools and teachers that they disagreed with. So I wanted to name that practice that’s been happening throughout history, so I call it “educational arson.” It’s connected to an interrelated idea of epistemicide, which is the destruction of ways and understanding the world that Boaventura De Sousa Santos developed. Epistemicide is really about erasing ideas that don’t conform to dominant colonial paradigms. It’s a form of intellectual violence that marginalizes alternative forms of knowledge. So educational arson is one tool that radical extremists of the uncritical race theorists use to destroy systems of knowledge that challenge racism. And there’s a lot of important examples. I’ll give you a couple of them.

The Spanish Bishop Diego de Landa came into contact with the Mayan people in 1562. When he met the Mayans, we’re talking about a culture that was over 2,000 years old. The Mayans had produced some of the most important advancements of any society on earth. They were probably the most sophisticated astronomers, mathematicians, agriculturalists, and linguists of any people on earth, and the Mayan books they wrote recorded their civilization, their religion, their scientific breakthroughs, their mathematical theories, and their history. Then, on July 12, 1562, Spanish educational arsonists, these conquistadors, came and they burned every single Mayan text in existence in a giant conflagration. Four books were found that were spared. There’s four books left. But all of that history and knowledge was destroyed in a giant bonfire of epistemicide, and that’s a tactic they’ve used over and over again throughout history.

During Reconstruction, educational arsonists burnt down over 600 schools. These were Black schools. Black people were building the public school system. We have to know that Black people built the public school system in this country. There were public schools before Reconstruction in the North, but how public can we really call them when they didn’t accept Black students? And in the South there were no public schools. So it was Black people who built the public school system in this country, and the Ku Klux Klan found that to be a great threat to their power, and used the flame and kerosene in their attack.

Also during the Reconstruction era, there was the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice, and this organization had as its emblem a book burning. That was its official seal and it was headed by a man named Anthony Comstock. If Anthony Comstock was alive today he would just take the light in today’s truth crime laws and today’s educational closeting — what I call educational closeting are the ideas of the Don’t Say Gay laws — because Comstock passed a series of laws known as the Comstock Laws, which were (in his mind) about eradicating obscenity. Here’s his idea of obscenity: he wanted to ban Walt Whitman’s poetry collection Leaves of Grass; he wanted to ban anatomy textbooks because, after all, they show naked bodies; [and] he wanted to ban anything that provided women with information about contraception. And in 1934, Comstock’s Society oversaw the destruction of an estimated 15 tons of literature, over 476 books, over 11,000 magazines, and 100,000 pamphlets.

And educational arson is still a tool they use today. There was a wave of arson attacks on Black churches in the 1990s that attacked Sunday schools. In 2016, it was a bomb threat on John Muir Elementary School in my hometown of Seattle that launched the Black Lives Matter at School movement to press back against those educational arsonists. You might remember Black History Month in 2022, there was a series of bomb threats against many Historically Black Colleges and Universities across the U.S.

One of the most famous recent examples of educational arson came in September, I think it was September 2023, and people may have seen this viral video of Senator Bill Igle, who was campaigning for governor using a flamethrower to torch a stack of boxes at a fundraising event. In the video he said, quote,

I am taking a flamethrower to cardboard boxes representing what I’m going to do to leftist policies and RINO (Republican in name. only] corruption of the Jeff City swamp. Let’s be clear, if you bring those woke books to Missouri schools to brainwash our kids, I’ll burn those too on the front lawn of the governor’s mansion.

This is how outlandish the rhetoric has gotten from uncritical race theorists. And they don’t burn books because they fear the past, they burn books because they fear the future that those books could inspire.

Kaler-Jones: Wow! Yes, those stories and the connections that you’re making are just mind blowing. To think about how this has shown up time and time again, and still to this present day. Wow! There’s so much more to dive into.

[breakout rooms]

Welcome back, everyone. I hope that you had rich discussions [. . . .] Now, one way we support teachers in bringing this history to the classroom is with our Teaching for Black Lives study groups that we have all over the country. We have more than 70 this year [. . .]. Many members and leaders of those groups are in the session with us today. Check out that map and all of the different locations where study groups are located. Jesse Hagopian and Ursula Wolfe-Rocca describe the power of the Teaching for Black Lives study groups in a recent Truthout article, Teachers Turn to Study Groups for Anti-Racist Learning as History Is Whitewashed.

One of our study group coordinators who has been an active participant in the Black Lives Matter at School Week of Action and the Teach Truth Day of Action shared some remarks to share with all of you via video. So, this is Michael Rebne from Kansas City, Kansas.

Michael Rebne: Hi, everyone. My name is Michael Rebne. I teach at Wyandotte High School in the Kansas City, Kansas school district. The Zinn Education Project and the Teaching for Black Lives book and study guide has been an amazing support for us at my high school, and I’m so happy to get a chance to talk briefly about it. One of the barriers our Black students in particular face is the criminalization that is part of white supremacy. Often, whether Black kids are in the majority or not, our Black students have higher rates of discipline and suspension than other students, especially for generalized and often dubious infractions like disrespect.

The opportunity to adapt a group that was examining the attitudes of our mostly white teaching staff to Teaching for Black Lives and work to center the experiences of our students and Black teachers was a huge boost to us. Several years ago in school-wide PD sessions, we organized through the support of the group. We strategized ways to alter our teaching, to center our students. We elevated and supported the voices of Black educators at our school who shared their experiences of being forced into roles as disciplinarians and racism educators with, of course, no additional pay. Our school even hired a restorative practices coordinator as a result of some of our work that helped us shift away from the punitive discipline that often targeted our Black students, and vitally this helped us launch both the Teaching for Black Lives Week of Action at our school and the Teach Truth Day of Action. In both cases, we’ve collaborated with Black-led community groups that work in areas like police accountability and voting rights, and critically, the school PTSA. I’m so excited this year to once again participate in the Teaching for Black Lives Week of Action, and I hope you choose to form a study group as well. I wish you so much success in justice in 2025.

Kaler-Jones: Thanks so much to Michael Rebne from Kansas City, Kansas, for that great description of the work that the Teaching for Black Lives study group was able to accomplish and work together to move collectively forward their school district and their school. [. . . .]

Alright, let’s get back to the conversation. We’ll bring Jesse back in to dive into some of the resistance that’s happening today. So, Jesse, you got to surprise some of the groups and chat with the folks in the groups which is awesome. There are so many teachers who are in this space today, teacher educators, librarians, historians, community members who are already a part of this resistance, but Teach Truth and the Teach Truth movement really celebrates the resistance. What are some examples of the resistance from what you share in the book?

Hagopian: Really the heart of this book are the stories of students and parents and caregivers, and especially educators at all levels, and administrators who are fighting against these truth crime laws, who are courageously teaching the truth even where it’s illegal to do so. I also tell the story of the work of the Zinn Education Project and Black Lives Matter at School, the African American Policy Forum, and other groups like H.E.A.L. Together that are at the forefront of providing tools and frameworks for educators to fight back.

I just want to tell the story of one particular educator who was fighting these truth crime laws. Do people remember the story of Summer Boismier, a high school English teacher at Norman High School in Oklahoma? Her story was just really remarkable, and I tell it in the book because her administrators were really scared of what could happen under Oklahoma’s new truth crime bill, which was HB 1775, and it restricted how race and identity could be taught and which books you could read. They wanted teachers to get rid of all the books until they knew which ones were safe. What Summer did was a really innovative form of resistance. She covered up all the books in her classroom with red butcher paper. But she didn’t stop there; she then took a black marker and wrote “Books the state doesn’t want you to read” in large letters across the butcher paper.

And she didn’t stop there. She added — really a stroke of genius — a QR code that provided students a link to apply for a Brooklyn Public Library card which would grant them access to any online book in their collection, in any state. Then she added a note next to the QR code that said, “Definitely don’t scan this.” There was no law stating that you couldn’t tell students to scan a QR code. There was no law that said you couldn’t tell students definitely don’t scan it. But nonetheless, the administrators put her on administrative leave and the Oklahoma Secretary of Public Education, Ryan Walters, even sent a letter to the State Board of Education demanding that Summer have her teaching certificate revoked.

And then she just faced an onslaught of hate. She said that she was getting messages saying that she should be lynched or sterilized. Just all kinds of hateful stuff. And like so many educators that I interviewed in this book, she just showed an incredible amount of courage to say, “I refuse to lie to kids,” and practice what Jarvis Givens calls fugitive pedagogy.

I interviewed Matthew Hahn, who was fired in Tennessee, and Amy Donofrio, was fired in Florida, and I also interviewed who maybe we could call the protagonist of this book, James Whitfield, who is the Black principal in Texas who was pushed out when he sent an email to his school community after George Floyd was killed saying that systemic racism is alive and well. I think one of the most important parts of this book is learning from the educators who have looked back at history, studied it, and are implementing it today. We tell the story of how the national Day of Action to Teach Truth was launched with the Zinn Education Project and Black Lives Matter at School. Many thanks to Deborah Menkart, who has spent endless hours helping to organize this movement across the country, to Tamara Anderson from BLM at Schools, and Julia Salcedo, who has put in so many hours. So many people behind the scenes have put in the work to coordinate this effort across the country, and it’s resulted in some extraordinary forms of resistance.

One of my favorites has been the historical walking tours. They’re not your ordinary protests, because educators have found places in their community that reveal something about the Black Freedom Struggle, or about systemic racism, and have gathered their community together to show them the history we’re talking about is all around us and we can’t allow them to criminalize it. In Michigan, the group organized a gathering at the very site on the train tracks where Malcolm X’s dad was lynched and then marched from that spot to the hospital where his dad ended up dying and gave out banned books to all the kids in that hospital. And they kept this history alive that way. In Seattle, we did walking tours to show where the Black Panther Party free healthcare clinic was started that still is in operation to this day. And many other places. So I’m excited to say that we’re organizing our 5th annual Teach Truth Day of Action on June 7, 2025. It’ll be rolling actions up to June 7. We will be supporting these actions across the country, and there’s so much good information that we will be providing to folks for how they can participate.

Kaler-Jones: Yes, I’m so in awe of all of the educators across the country who have publicly pledged and also just done so in their classrooms to teach the truth, regardless of the law. And to see how you are telling the story of the movement, especially at a time where they’re trying to erase this history, you’re putting it in print to pass down, I think, is so critically important that we have this resource to be able to share the story of the movement. So thank you. Speaking of resistance, the concept of the “radical healing of organized remembering” plays a central role in your book. What does this mean and how can educators engage in it as an act of resistance?

Hagopian: Yeah, thank you. You know, I was reading a book by the critical pedagogue, Henry Giroux, and this book was titled The Violence of Organized Forgetting, and he talks about how curricular violence is used to maintain racism, militarism, privatization, and a lot of forms of oppression. I think the violence of organized forgetting is such an important framework for understanding the current attacks on education right now. But I also wanted to think about how we heal from that violence. Someone I think both you and I both really love, Cierra, is Shawn Ginwright, and Ginwright writes a lot about healing-centered education. He developed this concept of radical healing which he wrote, quote, “radical healing refers to a process that builds the capacity of people to act upon their environment in ways that contribute to the well-being for the common good.” So, in this context, I think the radical healing of organized remembering is about identifying collective efforts in education, but also in social movements, to uncover the historical lessons that they’ve purposefully concealed — the historical lessons that they are trying to hide from our kids, that they are trying to hide from social movements.

I think recovering those historical lessons are really vital for recovering from historical trauma that many of us face, and they’re also crucial to building healthy movements for social justice. I think that trauma is not only inflicted by physical acts of violence, but also by the erasure and distortion of history. And I’ll just tell a quick story that I think really, I didn’t have the language of the radical healing of organized remembering at this time, but I think it’s a good example of what I mean.

When I started teaching at my alma mater, Garfield High School, back in 2010, I was given the AP U.S. history course to teach. I’ve got to say, I was really nervous to teach that course, because as a student at Garfield High School I never took an AP class. I didn’t think those classes were for me. They didn’t have Black kids in those classes, and so I kind of felt like an imposter there — even as the teacher — like I didn’t really belong there. And a lot of white parents didn’t think I did, either, and were very forthright about being concerned that I wouldn’t be able to get their students prepared to pass the AP exam. That was a really hard situation, and there was a lot of pressure to teach to the test. But you know that just isn’t me. I couldn’t do it.

I just went to the Zinn Education Project website and used almost every lesson I could find, because I wanted to engage the kids in collective discussions about history and how to use that history today. We did the abolitionist role play, where students are members of different abolitionist organizations and they have to debate each other about which strategy works the best for fighting and ending slavery. We did role plays about the fight for women’s right to vote simulations, about the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, where all the youth are members of SNCC and they have to debate what the best strategy is for the civil rights movement. We did all these interactive lesson plans about every social justice issue I could find, and in the end the students did very well on the AP exam — even though we hadn’t prioritized teaching to the test.

But I told them later that that’s not actually when they passed my test. It was the next year when the state legislature announced that they were going to cut billions of dollars from the education budget in the wake of the Great Recession, and our state constitution says that education is the “paramount duty of the State,” meaning they have to fund education before they fund anything else. So a group of us in a group called the Social Equity Educators organized a plan to disrupt their budget cutting session, and we went to the state capitol with many thousands of other protesters. We actually got into the House Ways and Means Committee meeting, where they did the budget cutting session, we mic checked the room, and we read out the state constitution. We announced that it was their paramount duty to fund education and we said that we were at the scene of a crime, that they weren’t just committing any crime, they were breaking the highest law of the state. At that point, I asked them to come into my custody for a citizen’s arrest, and I even brought out some plastic handcuffs and dangled them in the air, and then the police officer didn’t agree with my interpretation of the law and ended up arresting me instead of the legislature, if you can believe that.

I spent the evening in jail. But my students found out what had happened on the news, and then the next day I came to school and one of my students who was in that class in my AP U.S. history class had organized a Facebook page called “Free Mr. Hagopian.” So he took credit for my release. But then the following day, in 24 hours, he changed the Facebook page from “Free Mr. Hagopian” to “Walk out against the budget cuts.” They organized a committee where they created a pamphlet that showed what the budget cuts were going to do to Garfield High School. They made signs and flyers, and over 500 students marched out of Garfield High School to City Hall and demanded an audience with the mayor. They got their picture in the New York Times, they organized a citywide coalition, and then organized a citywide walkout of schools all across the city. They just put immense pressure on the state, and only a few weeks later the state Supreme Court ruled in their favor, saying that yes, the state was in violation of school funding policy. It was just this awesome victory for our movement, and to me that really showed what the violence of organized forgetting was about, and also what the healing of organized remembering is about. These students had learned how to organize social movements in my class. They had learned the lessons of almost every great movement I could find, and then they applied it in the real world. That’s what uncritical race theorists are scared of. They’re not scared that we’re shaming white children; they know we’re not shaming white children. What they really fear is that we’re empowering white children to be part of a multiracial uprising that will demand the schools and society that our children deserve.

Kaler-Jones: Wow! I’m speechless. So, since I’m speechless, I’m going to pull from something that you wrote. One of my favorite lines from your book is, “Honest educators are blues singers. They tell history like it is, and they know how to improvise, to bring the class into harmony.” I think the story that you just shared exemplifies what it means to be an honest educator, especially at a time of so much backlash, of so much violent erasure, how there’s still so much resistance, there’s still joy, there’s still creativity. There’s still friendship and camaraderie and truth teaching. So, Jesse, thank you so much for teaching and sharing these stories with all of us. Y’all, you’ve got to get this book, Teach Truth: The Struggle for Antiracist Teaching. Jesse, yay, amazing! I’m so happy for you, and I’m so happy for this resource.

Hagopian: Thank you, thank you, thank you, Cierra. I hope folks will order the book and not just read it, but use the lessons to build a new uprising. We need the new uprising to break through the kind of McCarthyist society that we’re living in today, just as the Civil Rights Movement broke through the last one. I hope that the book has lessons for folks, and I can’t imagine a better way to launch this book than in dialogue with you, Cierra. This has just been so joyful. I really appreciate you.

Kaler-Jones: I appreciate you, Jesse. Thank you.

While this transcript was edited, there may be minor errors or typos — if you notice something you believe to be incorrect, please contact us at zep@zinnedproject.org.

Audio

Listen to the recording of the session on these additional platforms.

Resources

Here are many of the lessons, books, and other resources recommended by the presenters and participants:

Lessons and Curriculum

|

Subversives: Stories from the Red Scare by Ursula Wolfe-Rocca Teaching SNCC: The Organization at the Heart of the Civil Rights Revolution by Adam Sanchez Testing, Tracking, and Toeing the Line: A Role Play on the Origins of the Modern High School by Bill Bigelow What We Don’t Learn About the Black Panther Party — but Should by Adam Sanchez and Jesse Hagopian Teaching for Black Lives, a teaching guide edited by Dyan Watson, Jesse Hagopian, Wayne Au (Rethinking Schools) |

Books

Articles and Podcasts

|

People’s History Podcasts for Young People, including the podcast mentioned in the chat, Empire City. More than McCarthyism: The Attack on Activism Students Don’t Learn About from Their Textbooks, an article by Ursula Wolfe-Rocca (from the If We Knew Our History series) “These People Are Frightened to Death”: Congressional Investigations and the Lavender Scare, an article by Judith Adkins, Prologue Magazine, Summer 2016, Vol. 48, No. 2 (National Archives) |

Take Action

|

Teaching for Black Lives study groups — read the book and start a study group today. Teach Truth Day of Action 2025 — join us to defend the freedom to learn. |

This Day In History

The dates below come from our This Day in People’s History collection, which contains hundreds of entries all searchable by date, state, theme, and keywords.

|

Sept. 9, 1739: The Stono Rebellion May 21, 1796: Ona Judge Escapes Enslavement by President George Washington July 29, 1835: Abolitionist Literature Removed from Post Office and Burned May 1–3, 1866: Memphis Massacre Jan. 7, 1868: Mississippi Constitutional Convention Jan. 9. 1873: Convention of African Americans Discuss Education Aug. 21, 1939: African Americans Arrested for Going to Public Library April 23, 1951: 16-Year-Old Barbara Johns Leads a Student Strike March 1, 1954: The Green Feather Movement Launched July 16, 1960: Greenville Eight Stage Read-In at Local Library March 27, 1961: Jackson, Mississippi Library Sit-In April 1, 1965: Blackwell v. Issaquena Board of Education Feb. 24, 1969: Tinker v. Des Moines Case Wins Free Speech Rights for Students June 28, 1969: Stonewall Riots Jan. 4, 1977: Students Successfully Sue School Board Over Book Bans Feb. 28, 1997: Teachers Suspended for Chicano Studies Lessons |

Participant Reflections

With more than 200 attendees present, the conversation and chat was lively, engaging, and full of history, teaching ideas, and more. Polls showed participants included 42 percent K–12 teachers, 21 percent teacher educators, 5 percent family of students, and more.

Here are more comments that participants shared in their end-of-session evaluation:

What was the most important thing (story, idea) you learned today?

It was incredibly eye-opening to hear about the heinous policies, bans, and laws that are happening today in America. It provided me with a sense of urgency to take action.

The idea that “educational arson” is prevalent all over our country, but teachers are standing up. Teachers risk their jobs and make changes to history by teaching true history!

The importance of courage and resistance.

Thinking of the CRT and “don’t say gay” backlash against educators as part of a continuum of white supremacist suppression of education going back to the first anti-literacy laws.

Teaching the truth is vital for radical healing.

Teaching the truth matters, and primary sources are key.

One of the most important things I learned today was the story of Jesse’s class organizing a walkout to protest an anti-education bill. It really made me emotional and was a super clear example of how education is fundamental to this movement. The story showed also how important young people’s voices are, which I will take into account as a young student.

I found Jesse’s story about reconnecting with his ancestors after finding the plantation where they were held as slaves very moving and impactful.

It is encouraging to understand the network that is supporting educators in teaching authentic Black history.

The term “uncritical race theory.” It’s a helpful way to think of it. And to also bring the term uncritical to other things I see happening in my school district.

I learned that “truthcrime” laws are a new version of everything that white supremacists have thrown at the struggle for liberation. Teaching about this history means teaching about resistance.

Jesse‘s application of new terms (or terms I haven’t considered in this context) are so helpful in unpacking the weight and layers of both historic and modern situations people have persevered through to teach the truth.

What will you do with what you learned?

Share knowledge with other teachers and work with others to pass a bill (already in the legislature) to prevent banning of books in schools and libraries.

I am going to re-write my curriculum to not only include absent narrative BUT to share with my students the history of educational activism.

Try to help the students I teach BE critical and know it’s OK to think about issues that concern them and the world around them.

I am inspired to talk about educational suppression and “educational arson” openly with my students, who are currently adults, so they can be more critical of their own children’s education.

I will not teach to the test. I will deviate from curriculum as much as possible and whenever necessary to tell my students the truth and give them the tools to use it.

I’d like to buy the book and get a group of white folks into a discussion to educate them on the historical truth of Black Americans.

Read the book and form a study group around it for the purpose of forming a collective in my community.

I want to make my lesson more active. I want students to actually engage and play out the history they’re learning about, not just read about it. It’s one thing to know the truth, it’s another to act on it, and my job isn’t done until they’re confident in acting on it.

I am thankful to know that there are resources and Teaching for Black Lives study groups that are going to help me once I become a teacher.

My lessons are consistently reinforced by Zinn Education Project and Rethinking Schools resources. We will also definitely be using Jesse’s book in our professional development workshops for our organization MapSO Freedom School.

How was the format for the class?

I love the links to resources, the breakout rooms work flawlessly, and I’m thankful for the follow-up email, the recording, and upcoming events.

Succinct and informative!

Another awesome session. I really enjoyed the speaker, and the breakout room was so informative.

The breakout session in the middle broke up the direct presentation, and I really enjoyed hearing from other people around the country. It makes you feel less alone.

Everything worked tonight. It was very exciting having Jesse discuss his new book right before it launches and to be part of such an important, historic night!

Presenters

Jesse Hagopian teaches Ethnic Studies and is the co-adviser to the Black Student Union at Garfield High School in Seattle. He is an editor for Rethinking Schools, the co-editor of Teaching for Black Lives, editor of More Than a Score: The New Uprising Against High-Stakes Testing, author of Teach Truth: The Struggle for Antiracist Education, and serves on the leadership team of the Zinn Education Project.

Cierra Kaler-Jones serves as the executive director of Rethinking Schools. Cierra is also on the leadership team of the Zinn Education Project, which Rethinking Schools coordinates with Teaching for Change, and has hosted many of our Teach the Black Freedom Struggle classes. Cierra is a teacher, a dancer, a writer, and a researcher. She previously served as director of storytelling at the Communities for Just Schools Fund.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn