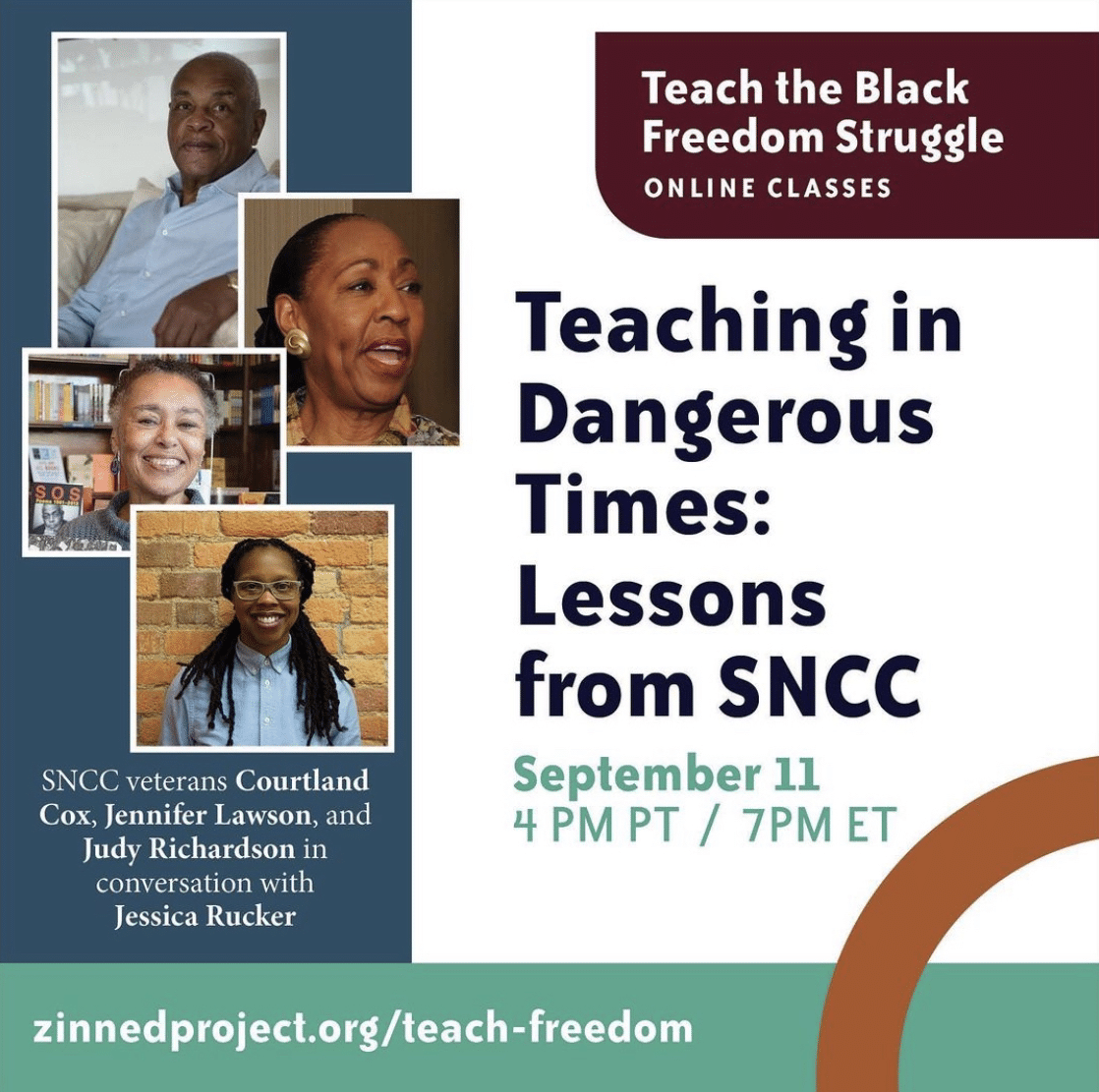

On September 11, Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) veterans Courtland Cox, Jennifer Lawson, and Judy Richardson joined educator Jessica Rucker to discuss key tenets of their work that we can draw on today.

This session kicked off the 2023–2024 season of our monthly Teach the Black Freedom Struggle online classes. Don’t miss this year’s lineup — register now.

Participants shared what they learned and the impact of the session:

It’s so inspirational to see the vitality and passion of the SNCC veterans after all these years of organizing. It’s a reminder that this work brings joy in the midst of years of challenges and that determination is the key factor, not bravery.

Storytelling is powerful; it’s what kept me at the edge of my seat wanting to learn more.

I learned the danger of lost histories and the increasing injustice that comes with banning and eradicating information.

Mr. Cox’s discussion on why white supremacists attack education was profound — in terms of framing the critical role of educating not only BIPOC individuals, but also white individuals at predominantly white institutions. The latter point will be very helpful for convincing my white colleagues why we should be spending time on these topics.

It hit hard just how much SNCC history is relevant today.

The resources on the SNCC website are amazing and I am so excited to use them with my students. I loved hearing the stories directly from the people who participated in these protests and, as a high school teacher, I think my students will be similarly inspired as activists who are finding their voices.

In addition to the conversation with these SNCC veterans, participants heard from teachers CJ McDermott and Tina Tosto, who described using SNCC lessons in the classroom and how empowered their students felt after learning this history.

Event Recording

Recording of the full session, except for the breakout rooms.

Transcript

Click below for the full transcript with resources mentioned in the discussion.

Transcript

Jesse Hagopian: It’s so wonderful to be in this virtual community with you all, and we’re so happy to be relaunching this invaluable [Teach the Black Freedom Struggle] series. These classes are hosted by the Zinn Education Project, which is coordinated by Rethinking Schools and Teaching for Change, as part of the Teaching for Black Lives campaign.

We have members here from the Teaching for Black Lives study groups. Shout out to y’all; if you are in one of those groups, please put T4BL after your name. The Zinn Education Project offers free downloadable people’s history lessons that many of you have probably already used for middle and high school classrooms. We also have a very important lesson and report on Reconstruction that we hope everyone will check out and learn how to teach the truth about Reconstruction.

I want to note that today’s session is on September 11th, which — in addition to the anniversary that we all know here in the United States — is also the 50th anniversary of the U.S.-backed coup in Chile, and other events of note that you can see on the slide and in the chat.

I want to just say some notes about our plans for our time together. We have ASL interpretation provided by Krystal Butler and Tyriibah Royal-Lampkins, and we will do short evaluations at the end. In about a week we will share the full recording of this session and all the resources you shared in the chat box. For PD certificates we’ll need your evaluation, so be sure to submit that to us. Then, after about 25 minutes of this invaluable discussion, we’ll pause so that you can meet each other and talk in small groups to share your thoughts with one another. Those small groups are really where so much of the deep learning occurs.

I’m very happy to welcome the esteemed Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee veterans, or SNCC veterans, who each played an active role in SNCC at a young age. Their profiles from the SNCC Digital Gateway are in the chat. Their accomplishments, truly, would take the rest of the session to recount. So I want to just introduce them briefly, with a highlight from each one. You’ll learn more about them in the course of the conversation. We are honored to have Courtland Cox with us, chair of the SNCC Legacy Project. We’re honored to have Jennifer Lawson with us, who served as the first chief programming executive for PBS. And we are very honored to have Judy Richardson, who was the series associate producer of the award winning PBS series, Eyes on the Prize. They will be interviewed by our longtime colleague, Jessica Rucker, a former high school teacher in D.C., and now a doctoral student and a truth teacher. Thank you so much, Jessica, for hosting this session. I will turn it over to you.

Jessica Rucker: Thank you. Thank you so much, Jesse, and hello to the audience. I’m so grateful to my guest speakers. Let’s just jump right into this thing, Jesse. We’re in dangerous times right now and I’m going to direct our three guest speakers today, as SNCC veterans, were working in areas that were so dangerous that other civil rights organizations feared to even consider taking them on. You were behind what Bob Moses called the “cotton curtain,” and we want to learn from your experiences and about your analysis and approaches so that we can use them today. The three of you continue to be active, so this is not only drawn from the 1960s, but on your decades — and I want to underscore decades — of organizing and leadership.

Throughout the session, like Jesse mentioned earlier, we’re going to be sharing links to the SNCC Legacy Project website and other related sites, and we want everyone here to share them, too. As a former teacher, I’m just going to say that’s your homework. Let’s start with the questions. Judy, I see you’re in my line of sight now, so I want to start this question off with you. If someone has never heard of SNCC, which would be so understandable given the textbook erasure of grassroots organizing, how would you describe SNCC in just a few sentences?

Judy Richardson: First of all, just thanks. I want to begin by thanking the Zinn Education Project for inviting us, [and] for all the years of emerging work that you and your team do to expand the larger human rights struggles. As you know, we at the SNCC Legacy Project continue to value our really long collaboration with you guys. And of course, I always love learning from these sessions when I’m an attendee. So I’m on the other end and this is really surprising. Anyway, I’m going to give you SNCC in three minutes.

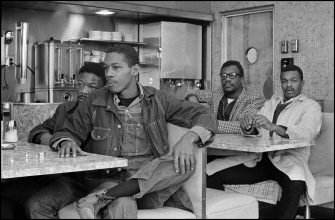

SNCC was founded in April 1960, by activists from the student sit-in movement, a movement that mushroomed throughout the South after that Greensboro, North Carolina sit-in one month before in February 1960. The movement was grounded in the activism of Black students at HBCUs. These students were then brought together by the legendary strategist and organizer, Ms. Ella Baker, at her alma mater, the HBCU Shaw University in North Carolina.

At that first meeting that she called, Miss Baker cautioned the students to think beyond integration — that the struggle had to be bigger than a hamburger and that it had to deal with whether people could afford that hamburger. Ms. Baker was SNCC’s political mentor, grounding the organization in the concept of building bottom up, grassroots leadership, moving away from demonstrations to effective long-term organizing. Not demos, but organizing; [they’re] not the same.

So SNCC soon became an organization of full time youth organizers working in rural areas of Mississippi, Alabama, southwest Georgia, and Arkansas. We lived in the communities where we organized. The primary issue was voting rights. Basically, how do you get Black people registered to vote without getting them killed? And economic justice. SNCC was the driving force behind the continuation of the 1961 Freedom Rides, through Diane Nash’s leadership, as well as 1964 Mississippi Freedom Summer, which included the establishment of free health clinics, Freedom Schools, and a voting rights campaign that was propelled by the formation of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party. Many remember the speech by the MFDP’s Miss Fannie Lou Hamer at the Democratic Party Convention that year. “I question America.” A lot of us on this call notice SNCC chairs have included Marion Barry and John Lewis, and in 1966, SNCC’s Stokely Carmichael and other SNCC organizers had been up — including the 3 of us on this call — had been working with local leaders in Lowndes County, Alabama to organize an independent Black political party with the black panther as its logo.

Stokely had just been elected SNCC chairman when he raised the cry for Black Power on a Mississippi voting rights march. That slogan reflected a fundamental concept that had long grounded SNCC’s organizing. It didn’t just pop up in 1966. I’ll end with this. SNCC was always guided by the concepts Ms. Baker spoke about at a 1964 Mississippi mass meeting for the MFDP. She said, “Even if segregation is gone, we will still have to see that everyone has a job.” And she meant everybody, not just Black people. “Even if we can all vote, if people are still hungry we will not be free. Singing alone is not enough,” she ended. “We need schools and learning in Hattiesburg.” Miss Baker. Alright, take it over.

Rucker: First of all, it looks like you’re in your living room. I’m in my living room and just learning that this movement was bigger than a Big Mac, right? And that we need schools and classes in session right now. So I have my notebook out and I hope other people do, too. I want to swing over to Jennifer and Courtland. And Judy, I want you to stay right here with us. But my next question is, why do you all think that the right, and I mean the politically conservative of this nation, why is the right prioritizing an all out attack on education at this time? Miss Baker said, “We need schools.” So what’s this all about?

Courtland Cox: I think it’s very clear, what we find today, and what we see today, what has been happening in this country from the beginning. The reason you see the all out attack on education is part of the larger scheme to frame the narrative from which decisions are made about this country.

So, whether it’s that denial of information in terms of education, whether it’s lying (such as Stop the Steal), whether it’s the view that they’re making up about women and their ability to control their own health, whether it’s about the LGBTQ communities, it’s always about a narrative that says that you have no value, and we [do] have value, therefore we’ll begin to make decisions about you from the the narratives that we create. So it’s really about who’s going to set the agenda. It’s really not only just about education, [though] that’s the way it’s manifested. It’s really about the big question in this country of who sets the agenda.

Jennifer Lawson: I agree fully with Courtland. I think it’s about defining who’s in control, who’s going to set the agenda, [and] who’s going to have the power. And that’s something I think we’ll need to talk about as the evening goes on, which is power, and not be afraid of power, and think about roots to empowerment. Because the people in charge make up the stories and make up the lies, and we then become the victims of that, and that’s not a place that we want to be.

One of the things that I loved is that when I grew up in Alabama, when they were trying to deprive us of a decent education, I appreciated that the community stepped forward and created, for example, libraries for us. Our parents worked together to create libraries. I mean, they didn’t have the best books in the world, but they had books, and they were teaching us the importance of learning and the importance of doing for ourselves. So I do think that power and the way in which people are deprived of information and correct information is something that is a key part of keeping people down and subjugated. It’s really important for us to always rise above that and to teach our children and to learn ourselves how to overcome those problems.

Rucker: This is powerful stuff. I want to stay here with power for a bit. So, you all talked a little bit about power, but I want to pull out a little bit more. Some of the systems and structures that we’re specifically against. We know right now books are being banned, libraries are being closed. Tell us a little bit more about what systems and structures of power we’re up against, and say a little bit more about who right now is controlling these narratives.

Cox: A couple of things. I want to go back to 1963 for a minute. Bob Moses always talks about this example, and Bob Moses, he was in a courthouse, and I think Judge Clayton, when they were bringing people down to register to vote, the judge said, “Why are you bringing these ignorant people down here to register to vote?” And Bob and others pointed out to him that he created the educational system, it wasn’t just people making statements about education. It was an educational system based on keeping people as sharecroppers. So education has served as a way of the time, determining how people would be able to be positioned in this country. My sense is that education is connected to almost every aspect of life in this country, and the example I just wanted to point out, with the federal judge pointedly saying that people who were ignorant should not vote, and therefore it is so, and they should be maintaining a position of subservience in the cotton fields and never rise to anything. So, I mean, I think we have to understand the connection between education and all the other aspects, that it doesn’t exist in isolation.

Rucker: Do Jennifer or Judy want to add anything?

Richardson: Yeah, just a quick thing. Because certainly it’s focused on Black kids, but what we’re also seeing is that the right, the white supremacists that are in control now in many of these states, also don’t want white children to understand. It’s kind of like what was happening when I was teaching at Brown, these were kids who said, “I’m coming from the crème de la crème of schools.” And they said, “How come we didn’t know this?”

So it’s not that Black kids are being oppressed. White supremacists want to make sure that their kids and their kids’ kids do not learn about the reason that white people are on top, because the whole premise of white supremacy is that you’re better. Well, if you learn about redlining, and you learn about this, you learn about all the structural suppressions that have been put in place since we got here.

Then it’s not just that. “My grandfather came over here from Italy. He couldn’t speak English, and in five years he worked hard” — which is not what we do right — “he worked hard enough that he was able to get the money for his store.” Everything that they say is with the idea that the reason they’re on top is because they’re better. Once you give them information, that it’s the structural stuff that prevents Black and brown and a lot of other people from getting equity, then that doesn’t work anymore and the whole construction of white supremacy falls apart. They don’t want their kids to know.

Rucker: What I’m hearing from you all is this idea that when we have systems and structures that seek to limit what people can learn, that’s one of the ways that white supremacy — and I would even advance anti-Blackness — maintains itself. But what I’m also hearing is that education isn’t limited to what we do through institutions like schools and libraries. Those are the social institutions that are set up. But what I’m also hearing, as somebody who’s not in the classroom anymore as a public teacher, that it’s still my role and my responsibility to be an educator. That’s why this class tonight is very, very important. So, I want to talk a little bit more now, this time, about how we gain control and seize power to get to where we want to be, to control that narrative. Because this is something I love about SNCC. We don’t just talk about the issues, we are thinking through and putting into action the solutions to gain control and to seize power. So let’s talk a little bit about what SNCC did.

Cox: I think basically the way we approach things is as an issue of problem solving. It may seem strange to talk about it that way, but there were problems ahead of us that we had to solve, and we had to use the various instruments that we had, as limited as they were, in order to solve the problem. I think that’s the same thing that we have today. We have a problem in front of us and how do we begin to solve it? Jessica, you just mentioned something that I think as we begin to think about education today and solving the problem we may want to start outside the schools in terms of churches, in terms of community organization, in terms of building a sense of humanity, because what’s very critical in terms of people becoming active and becoming serious is that they see themselves as worthy, they see themselves as actors, they see themselves as people who can make a difference and should make a difference. So, as we begin to think about what it is we are going to be doing, we should be thinking not only in terms of classrooms, as you mentioned, but we have the SNCC Legacy Project and SNCC Digital. People may want to do freedom schools in churches. People may want to just connect one on one. But I think that, and not to be overwhelmed by things. Let’s just look at it as a problem to be solved, and the steps that we can take to deal with it.

Lawson: That aspect of looking at it as a problem to be solved can be so, so very empowering for people of all ages, for kids as well as for adults in a community. It’s one of the questions that we sometimes get when we’re speaking like this. “Weren’t you all afraid? How did you get involved? Why would you do something like that when you were a young person?” We had problems. We were facing problems in our communities that we didn’t want to live with. We didn’t want to grow up in a society that was framed the way it was, and that’s what led us, then, to action. I think the whole idea of thinking and working with others to solve a problem, working with people who have that in common, you begin to develop and begin to understand the values that you have in common as well, and that helps to create a bond among you and among us that can then propel us forward.

Rucker: This is great. I’m thinking a lot right now about my 7-year-old niece, and just the gift of freedom schools and this idea that we are disrupting the false, pernicious, and violent belief that we’re not worthy, or that our work is contingent upon the labor we produce for this country. So this concept of the freedom school as being a collective space for liberatory education is really powerful. It’s my understanding from what I’ve studied really briefly that SNCC really taught history that was denied to us in structural and systemic ways. That we still found ways, as individuals and as collectives within a broader community, to say, Yeah, but what you’re going to learn today, Jessica, you need to know this truth.” Then can somebody say a little bit, I think there was a primer of some sort that came on through. Just give a commercial version of it, like the 30 second snapshot, because I want folks to see this, and some folks in school might want copies of this as well.

Richardson: SNCC was always about education. I mean, we understood that we had to flip it, you know. I mean, they were still in the South, they were still learning, and may still be learning, about the Civil War as the war of Northern aggression. So we always wanted them in freedom schools. For example, take the state constitution. Does this work for you guys, for those of you in your communities? Does it work even for poor white people? How would you change this? How would you change the wording so it works for you? It’s always thinking beyond what is to what could be and what should be.

We did a lot of publications as well. It was the freedom schools, it was a residential freedom school, a lot of materials. One of them was the book that you’re talking about, and it was done by one of the volunteers, Frank Cieciorka. He did illustrations, but the great thing is that the intro was done by Charlie Cobb, a wonderful SNCC person who has written a lot. It’s a history book about us. [From] Toussaint Louverture to Harriet Tubman. It has the kind of folks that you were not getting generally unless, somebody like Harriette Moore in Florida, and teaching this material from books hidden under the desk in your classroom. So we did it, and then I started doing distribution for it. The SCLC, Dr. King’s organization, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, was also interested in using the book for their citizenship schools. We were sending it up north to the northern freedom schools. So part of it was just how do you get this distributed once you’ve done it.

Rucker: Wow! First of all, yes, shout out to Aileen on the chat. These resources are there so please take advantage of them. I love that SNCC has so many nimble approaches to ensuring that we owned and controlled the narrative. Now I want to pivot just a little bit to talk about something that was referenced earlier, which is the SNCC Digital Gateway site.

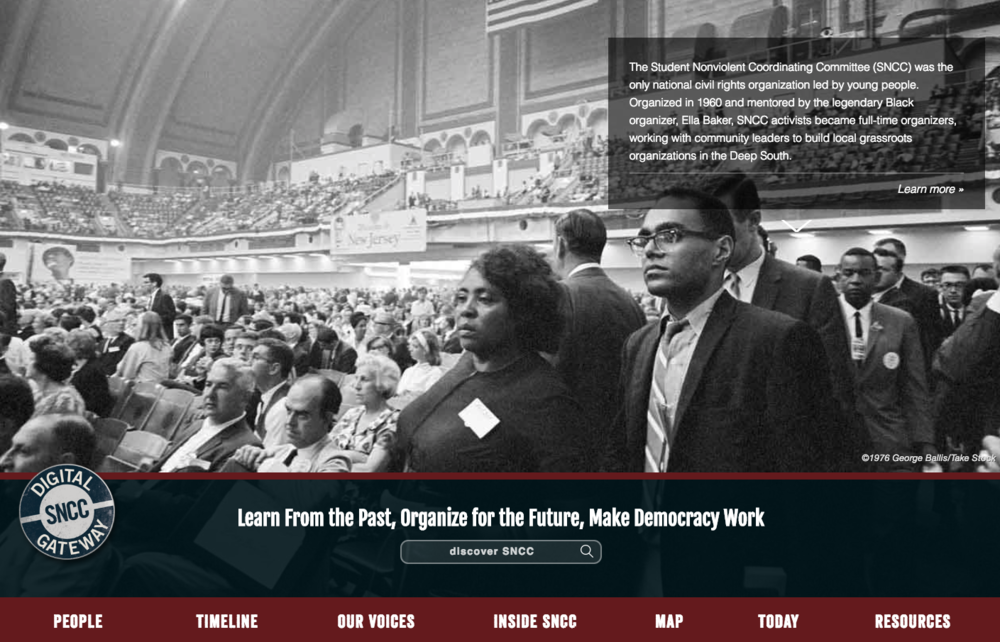

My students’ own responses to it, with the primary that we just saw, for folks thinking about “okay, how can I translate this now?” one of the things that some of my colleagues . . . I was in the electives department at the high school where I used to teach and we would create zines with students. We would use powerful imagery combined with language to help challenge these ideas of power and who had power. One of the resources that we often consulted when teaching students about liberation, challenging power, democracy and justice for all, and even the concept of the freedom school was the SNCC Digital Gateway website. What I loved about this as a humanities teacher, as a special education teacher, is that the site is accessible. There’s text, there’s audio, and there’s visual information, and my students love, love, love, love, love, love that they got to experience historical figures. These are not characters, these are real people who dealt with real issues and made real change. But they got to deal with historical figures in their own voice through personal bios, interactive timelines, interactive maps, and primary source documents including voice recordings and pictures. Something that really surprised my students when they got to the sections with the people and the bios, they were like, “But Miss Rucker, the little line after the dash, there’s nothing behind it. There’s no other year behind it.” And they were like, “So folks are still alive?!” And I’m like, “Yes.” “So that means, wait, they were younger when they were doing this?” I was like, “Yes, they were just like you, just like us.” And so I think this is another thing that they loved about our lessons, about SNCC, freedom schools, is that we were teaching freedom, rights, and Black liberation, and that it was intergenerational, that often there were youth who inspired adults like me to say, “Well, hold up, if you’re walking out, I need to, too.”

So, next round of questions. That’s enough of my narrative. I’m curious, and Courtland, why don’t you start us off, how does the leadership of women (this is ironic, alright, anybody could start.) But how does the leadership of women advance the work that was and still is necessary both during the Civil Rights Movement but also today.

Cox: I want to emphasize something that you just said. We were barely out of high school when we started on this journey of education. Most people in SNCC were between the ages of 17 and 22. When Bob Moses, who was 28 years old, was involved, we thought of him as an old man. We thought that you would never get beyond 30. So let people understand that we were 17 to 22, and we did the freedom schools, we in that same area. In terms of women in the movement, Judy and Jennifer, I just want to mention one person in particular who is one of my favorite people, Ruby Doris Smith Robinson. She was a person that ran the organization, and she was one of my favorites. She liked me and I liked her, and she controlled the money, so therefore I liked her even more. But I’ll let Judy go and talk about the Hands on Freedom Plow.

Richardson: One of the things Courtland said was that people talk about Jim Foreman, who was our executive director, running the organization, but in those early days it was Ruby who ran that organization.

Cox: The thing I liked about Ruby, she was both an inside person and an outside person. She ran the organization, she kept the books, she dealt with personnel, she dealt with all the administrative stuff that people did not want to deal with. And that was just in the morning; in the afternoon she would go on a demonstration and confront the cops. And if you wanted to be on a line with somebody who will go down with you, Ruby was there. So she was both an inside person and an outside person. Basically she embodied the ethic of what the students were at that particular time, especially in dealing with public accommodations and issues like that. She was a tough person who could run the organization in a way that was both efficient and also very personal, in the sense that she knew the people who worked in Alabama, she knew the people who worked in Mississippi. She knew all the steps, and she knew them in terms of their idiosyncrasies and so forth, and, unfortunately, she had an untimely death in terms of some health issues, but in terms of holding the organization together in the early days, it was her. She was both inside and outside.

Richardson: I would just mention, just picking up on something and not to just talk about Ruby, but Ruby was so important. When you mentioned Hands on the Freedom Plow, for example, a lot of us talk about Ruby Doris Robinson. I don’t get to SNCC until . . . because I’m doing some work on the campus where I am, at Swarthmore Campus, and well, anyway, Swarthmore College in Pennsylvania, and it’s my first year. Then I’m doing demonstrations in Cambridge, Maryland, and a SNCC person comes back who had been away and working in southwest Georgia, Penny Patch, and she says, “Well, I hear you’ve been getting in jail. Why don’t you take off the next semester of your sophomore year, the first semester of the sophomore year?” I’m on a full four year scholarship. It’s like, “Oh, I don’t think so.” But we worked it out, and the main thing about this is that Penny Patch says, “But since you’re coming from the north, you have to do an application to go on staff.” But she says, “In order to do that you’ve got to go by Ruby Doris.” Ruby Doris ran that place. Ivanhoe Donaldson, who was a close friend of mine, a legendary SNCC organizer, Ivanhoe said when he went to jail he got a letter from Ruby Doris everyday. People had a connection because they knew she walked the walk. She had done 30 days “Jail, no bail.” It’s in Rock Hill, South Carolina. She had done all that time, over 30 days in Parchment Prison on freedom rides. So when people talk about did women have to take it low? No, we had Miss Baker. We had Ruby Doris. We had Diane Nash. We had all these people, women whom the men in the organization saw as leaders. It was amazing.

Lawson: It truly was. I was 17 and in college at Tuskegee when we started our student demonstrations because we had problems at Tuskegee. It was a wonderful little bubble of a place, but if you went beyond the campus, then you found the same kind of racism that you’d find anywhere else in Alabama, Georgia, Mississippi, and other parts of the country. So we, as students, wanted to protest, we wanted to march, we wanted to make a change there. When I then met SNCC people for the first time, who were coming through on their way to Selma, generally it was astonishing to me how impressive the women were. I was impressed with everybody because you had these young men, too, who were really making change, and who were in their twenties.

We were all kids, but we kept feeling that, “Oh, there’s a problem. We can come up with a solution. We can work on this and that.” Every one of the women that I met during that time was so impressive to me that I then felt this is an organization that I would definitely want to be a part of, and it just kept getting better. Because then SNCC is also an organization that believes very deeply in working from the bottom up and from the inside out. When we would go to communities like when we were working in Macon County, Alabama, or Wilcox County, Alabama — notice I say county, because we weren’t working in cities, we were working in rural areas for the most part — and the women, the people that I met there were very impressive, in Lowndes County, in Mississippi, [like] Fannie Lou Hamer. So many people know her name, but then you had other people like Unita Blackwell, who then became the mayor of her town in Mississippi. There were all of these incredible, impressive women. And the book that Judy mentioned, Hands on the Freedom Plow, provides profiles of some of those very impressive women — over 52 of them are profiled in the book.

Richardson: This is an amazing profile, but in the sense that it is their own words, their own testimonies. For some we did recordings, like with Annie Pearl Avery. Honey, legend was she used to carry stuff with her, and we had to say, “Look, you’ve got to leave that revolver on before you get on the line.” So all about those women. If they didn’t want to sit down and take the time to write their own stories, then we would do tapes with them. We would transcribe it, let them see it, and put it in. They’re just lots of women whose own stories are in this book, 55 [of them], including Dr. Bernice Johnson Reagon.

Rucker: Thank you all so much. I love how you all are dropping Jim’s and dropping names. My notebook again just continues to fill up. I love it. We’re about to head into breakout rooms, after which we will come back and continue the conversation. Please do not drop off. We’re just getting started, basically.

Judy, you were talking a little bit about the 55 stories that are featured in [Hands on the Freedom Plow]. You mentioned a little bit about Miss Annie Pearl Avery. I’m wondering if you will be willing to share a little bit about who she was. I’m really inspired by her, because, she said, “I ain’t come off no college campus,” really challenging this idea of the education that Courtland was talking about. I don’t need to be formally educated to know that I can fight for freedom and rights.

Richardson: It was an organization where you could feel valued, where you realized you could make a contribution regardless. I mean, I’m coming from the North. I don’t know nothing. I felt absolutely amazed that people were accepting of me and said, “Oh, she can type. Okay.” I can do this with Annie Pearl Avery. She knew all these things. I mean, she knew the rhythms of the South. I didn’t know that. So I’m learning as I come in, and what was amazing about SNCC is that we understood what people could bring to the organization, what skills, what understandings they had, what experiences they had, that could be useful to the work. So for me, I was in jail with Annie Pearl, and what was amazing to me, we had just gotten arrested and I’m in there, and it was one of the few times — now, see, the thing is, I don’t want to start a story because I know we’ve got to go and break. So I’m not going to let you find that story. Annie Pearl Avery is alive and well and still as spicy as ever.

Rucker: I love it, but I have to cut you off. One of the reasons why what you’re saying about the knowledge and the skills that she brought, specifically about the South, why that’s so important is because folks like me were born and raised here in D.C. I had teacher colleagues who weren’t born and raised here, but what I love is when we can collaborate around shared values and shared goals. I can help share some of the history and context as long as we know that we are keeping our eyes on the proverbial prize, so to speak. Let me see, I had some other questions. What SNCC Digital Gateway resource should we be paying attention to?

Lawson: In that little moment that we have, I would say plunge into the site. I think you will find the SNCC Digital Gateway really well organized and, depending on how you want to cut it, you can get to the topics and get to information from so many different pathways. For example, we were just talking about Annie Pearl Avery. You can go to “People” and look up a person. If you’ve heard of Stokely Carmichael or somebody you want [to know more about], you can go to “People.” If you want to know what happened in 1964, you can go to the “Timeline” and it’s all laid out there in front of you. If you want to know, “Gee, when did this start?” the timeline can take you all the way back to the beginning, all the way back into the 1940s, to the groups and people that were predecessors of SNCC. So there are so many ways that you can plunge into that. If you want to know how this is relevant to today and today’s young people, there’s a section on today, where you hear the voices of young people who meet with us regularly to talk about what they are doing now.

Cox: Also there is a search engine where you can just type the name “Annie Pearl Avery” and everything across this platform will come up. So there’s a search engine.

Richardson: What’s great is that there are all these primary sources. What’s fascinating to me is, I’ll go on the site and I’ll see a leaflet from 1963 of Charlie Cobb going to so and so, or footage. There are a couple, like the women in SNCC, there’s a videotape of pieces of folks’ interviews talking about how they got into SNCC and what it felt like being a woman in SNCC. There’s lots of primary stuff, which is amazing.

Rucker: What I loved about it as a classroom teacher is that the sources are credible and reliable. Sometimes one of my biggest challenges was finding a central repository. Well, I couldn’t find one, but that’s what SNCC Digital gateway was. So from D.C.’s mayor for life, Marion Barry, students were like “That man was a part of SNCC?” “Eleanor Holmes Norton was part of SNCC?” Like Jennifer said, and like Courtland and Judy have said, it’s just such a multifaceted, accessible space, and not just for student learners, but for me [too]. When I need to do some background research before introducing students to content, I will watch the videos. I love engaging with movement leaders of today, being in conversation with SNCC veterans. It’s just an all out rich resource. No matter how old you are, there’s a piece of history reflected on the site that you will be able to connect with. That’s what I found, which I really love.

Rucker: The SNCC veterans wanted to hear from teachers who are teaching about SNCC, so we’re now going to have the opportunity to very briefly hear from two said teachers. I want to give them shout-outs in advance. Then we’re going to ask our SNCC veteran guests some more questions. If you have stories to share, please add them to the chat. First, I’d like to welcome CJ, a middle school social studies teacher in Forest Lake, Minnesota. CJ, tell us about using the lessons on SNCC by Adam Sanchez from the Zinn Education Project.

CJ McDermott: The last time I used it, I kind of adapted it a little bit. But this specific lesson, it’s been a couple of years, when I was student teaching. I was in a fairly conservative white school, kind of middle of nowhere, Wisconsin, and at this point I was teaching a unit on civil rights in a civics class. I really believe in hands-on learning. I think that’s really important. So I use the SNCC meeting role play lesson from the Zinn Education Project. In this lesson the students take on this role of a SNCC member and they have to come to this consensus as a group when faced with different dilemmas and problems and things like that. So, when they’re really asked to step into this history and choose which actions to take, my students overwhelmingly wanted to use direct action. It really opened up a lot of dialogues, and I just hadn’t seen this group ever so engaged. They really had good discussions and deliberations that they otherwise wouldn’t have had. I was really, really impressed by their insights, and many students come to me after these lessons and tell me that they never heard these histories before, and how much they appreciated me opening their eyes and helping them really learn more about it. I had a lot of them thank me, too, for helping them feel seen in the classroom.

Rucker: Thank you so much. CJ. Next, I want to kick it over to Tina. Tina teaches high school social studies in Mississippi. Tina, tell us about using the SNCC Digital Gateway website and lessons from the Zinn Education Project website, please.

Cristina Tosto: Sure. Well, I use these lessons in both my U.S. history classes and my African American studies classes, and I love teaching about SNCC because it really shows young people the possibilities that they have if they’re willing to wield their power and organize. I developed a lesson that’s on the SNCC Legacy Project site where students read an unnamed scenario based on real people from Mississippi during civil rights who are involved in SNCC. But the students don’t know that these are real people. So then students have to decide whether the person that they read about would join, like if they were in their situation, would they join in the Civil Rights Movement in the face of these circumstances. After students make their decisions, I reveal to them that all these people courageously said yes, and then I reveal the real identities of these people and they use the SNCC Digital Gateway website to learn more about their person.

Then I use a lot more websites, from the Zinn Education Project website, where I use the lesson that CJ used as well, with the SNCC meeting. Students conduct their own SNCC meeting and then they have to make decisions about what actions to take next. I’ve also used lessons about the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party and COINTELPRO.

We also watched the movie Freedom Summer, and I found that my students really connect with the individuals through the lessons, especially with being in Mississippi. So by the time we watch the movie students have a really good grasp on the courage and sacrifice of regular people, the different organizations, the goals, and the strategies of the Civil Rights Movement.

Rucker: Tina, first of all, I’m just glad that you’re still teaching this people’s history. We met a few years ago, but Freedom Summer did it for my students, too. That is a powerful piece. One thing that I want to let folks know who are still in a classroom, or who treat the world as our classroom, we actually are living in an era where teaching actual history can allow us to make history. If y’all don’t want me to be Black history, we’ve all got to start teaching this Black history right? Because our very futures are on the line. So thank you so much to CJ and Tina. Y’all rock. We’ve got to keep supporting our teachers, y’all, at every single level. But, I want to kick it back over to Courtland and Jennifer. We have questions about how do you stay strong in the face of real threats to your safety. How did you and how do you maintain your faith?

Lawson: For me, it is community. And it’s that when we worked, when Courtland and I worked in Lowndes County, I always felt protected because the people around us — the people with whom we were working, who were sharecroppers. Some were landowners, but many were sharecroppers — that they then had our backs. They fed us, they wanted to make sure we had gas for our cars, they wanted to make sure that we were safe, because they felt that we were there to help and work with them, and that always, they also would make us know that. “Don’t worry if that truck comes down this way. We have our guns, too. You are protected.” So it was a circumstance where I felt that the community was that protective shield for us during those times.

Cox: I’ve been on this journey for, I guess, 64 years, and probably most people on this call are not 64. What is interesting, what I keep in my head, is, I guess, three things keep going in my head. There’s a line from “Ella’s Song” that Bernice Johnson Reagon wrote a song and it says, “We who believe in freedom cannot rest until it comes.” What’s important and keeping people going all this time is a belief system. It’s intangible, but it’s a belief system. Just as people want to believe in democracy, or people want to believe in this or that, by my sense, people should be able to have freedom to reach their highest levels and their best lives. So that, to me, has kept me going for some 64 years.

Also what is important in terms of keeping you going is the part that Jennifer just talked about, that you have to be embedded. You have to. Even if you’re not living in that place in Mississippi — I’m no longer there — or Alabama, or all these other places. The sense of who I connect to is really important. Here’s one interesting example. Jennifer and I mentioned we worked in Lowndes County, Alabama and when I wanted to inspire and we worked to create the document to inspire the people in Lowndes County, we used the language and the concepts and the thinking of people we worked with in Mississippi, because we knew that if we were going to talk to the people in Mississippi, in Alabama, they were in the same condition, and we had to use the spirit of that community to transfer it to other communities. So my sense is that, one, having a fundamental belief system about freedom, and secondly, grounding yourself in the communities that you think you are trying to work with.

Lawson: I think another aspect of that is determination and focus, and being really clear about what I’m trying to do, and that even though obstacles may come in my way I’m going to stay focused on that. That’s where, again, some of the songs of the movement played such an important role. I mean, you’ve probably heard the stories of how, when we were in jail, oftentimes one of the ways that we would comfort ourselves and feel connected was because we could hear each other singing from one part of the building to another. But the song “Eye on the Prize,” for example, is another one that, for me, is like a little motto. It’s like a guide post that, when things are going wrong or bad — and that doesn’t necessarily mean in the movement part of my life; that could be in other parts of my life, as well — it’s about staying, keeping that determination, and staying focused. Or keeping my eyes on the prize.

Cox: Let me just say one thing about determination. People always kept saying, “You guys were in there and facing all that violence and so forth. You guys were pretty brave.” I said, “We weren’t brave, we were determined.” At the end of the day, when you look at what happened, if you go listen, look at, and read the WATS reports, where people day after day after day after day engage in trying to get to where they need to be, determination was the most important factor, not bravery.

Rucker: Go ahead, Judy, don’t even raise your hand, just unmute.

Richardson: All of that is really, really important, but you’ve got to find somebody else besides yourself that you can talk to, that you can relate to. This is too hard. I’m looking at this chat. Honey, teachers are getting jammed right and left. I mean, somebody who says they just got off a call with a teacher who just this evening got somebody saying, “You’ve got to come into the office because a teacher” — and it only takes one — “called you up because you taught something.” You’ve got to find somebody that can be part of your strength. It may be a fellow teacher. It may or may not be a principal. It’s got to be somebody who can work with you, who can help fortify you, because it’s too hard. You’ve got to be determined. You’ve got to. But you can’t do it by yourself, because it’s hard. What’s carried me through is all these people that you see and the people you don’t see, and work. I look at teachers, I mean, every time I get on one of these sessions it absolutely amazes me, teachers blow me away because they’re going into the classroom every day and changing the world. We did it in the movement, but you all are changing the world.

Rucker: The movement is still moving, through us and through folks in the classroom. I love this beautiful visual that we lift every voice when we sing and our song is a freedom song. My stay on freedom. This is a part of the song, too. This is a little part of the rhythm and the melody, what we’re doing here together. I love this idea that having a belief system, not just a wondering, but a deep knowledge that freedom’s going to come, this freedom dream. It’s so radical that we do it together. One of the other things I really want to drive home is whether it’s the butcher or the beautician, whether it’s the doctor, whether it’s the lawyer, whether it’s the principal or the teacher, not to create binaries or hierarchies, but to say that we are all responsible for this work of freedom and providing that protective shield that Jennifer talked about.

So, I want to ask just a couple more questions, and then I want to take some from the chat, because there have been some really great ones. If you could make it super concrete, because I will be taking my notes too, what recommendations do you have for teachers today?

Cox: First of all, the sense of realizing that there is an issue and there is a problem, and understanding that even as bad as this problem is that problems have been worse than what they even seem today. I know when it’s happening to you that’s hard to believe. But in fact, there is sense. I mean having the perspective that we’ve had, the situation was much worse, and the determination to make a difference is the real issue. Now, I think for teachers who are in these schools in Florida or in Texas, that may not be the place to make the fight. I mean it. You have to determine how you want to navigate that.

But, as Judy said, having other people who are like-minded, who you can sit down with and say, “Here’s the problem. We may not be able to solve it now, but what are your ideas? What do you think? How can we act in concert in order to make a difference?” I think the first thing I would begin to do is to look for like-minded teachers and like-minded educators and like-minded preachers and like-minded butchers and all these people to try to get as many like minds as you can. Because at the end of the day you want to have more people moving with you than they have with them. Because at the end of the day, I don’t care what the governor of Florida thinks as long as I’m not the governor of Florida. So at the end of the day, how do we now begin to create a collective effort that is both communal, both educational and supportive, but also political. Which says, we want people in these offices that will advance where we want to go. So my sense is that the first thing I would do is pick up on what Judy said, the like-minded people. How can we talk to each other, and it may take . . . and it’s not going to be media, it’s not going to be in the next six months, or eight months. It may take a year, it may take two years, but having the sense of like-minded people moving in the same direction is the most important first step.

Lawson: I think that this forum right here is one of those, is a part of that. I mean, the the fact that you can identify other people across the country through this Zinn Education Project, that helps you then know who else is experiencing this problem, that then begins to create more of this community that I was talking about. You begin to identify more allies, more people who are in a similar place to the place you’re in and who can then offer support.

Rucker: That’s right. Like these Teaching for Black Lives study groups, these monthly people’s historians online sessions are great places to build relationships with folks I like to call “curriculum comrades” because we’re vibrating on a similar political wavelength. Let’s do this. I want to ask a really practical question. Building on this idea of the intellectual tradition and strategy, I want you all to connect for us how you challenged unjust laws and what you think should be done today about teachers being told to remove books from their classroom or to lock their school library.

Cox: One of the things I tell people, and I know it sounds strange, is that what we’re seeing today in the classroom is not an issue of education solely — it a political issue. People are trying to reinforce a concept and a narrative on you. I mean, we’re not educators arguing this is the best way to teach, what to teach, and so forth. They are trying to establish a political view of the world on you, and I think you have to determine. That’s why I said that, and it may be a longer term issue than people want to understand. The thing that we have to do at the end of the day is make sure that these people who hold views that are inimical to our own interest never hold political office, or never be in a position to hurt us. And I think that the organizing has to be almost bigger than just the particular classroom that you’re in if you’re going to succeed.

Lawson: I just would echo what Courtland is saying, and say that I think that we you shouldn’t feel, as teachers, that this burden falls on your shoulders to make the change. Because this is a community thing, this affects all of us. It affects all of our children, it affects all of us, and the community needs to be a serious part of stepping forward to protect the teachers and to protect education in this country.

Richardson: I would also mention that the larger thing is really, really important because nothing’s going to change until you change the people who are creating all this chaos and white supremacy. But personally, if I’m a teacher and I know that my job is really at risk and I don’t know what I can say and what I can’t say. I mean, every time now that I go in that classroom I have to worry in a way I didn’t before about the kind of ideas that I’m asking them to just consider, not saying you should think this way or that way, that the teachers on this session are really asking for themselves about ideas that they are now presenting to them. So teachers are very much at risk. I guess I’m thinking about what we did in the movement, which is that there has to be some kind of network, so that these idiot school boards, who are being taken over by various people. That Moms for Liberty and Heritage Foundation, and all the folks who are against real education, that there has to be some way that they know, and the way that we did it, that somebody outside that little school board is looking at it and it can’t wait until the Washington Post or the New York Times or something does something. I think if there’s a way to create something, so that people start flooding that school board in the way that we did, we would contact the Friends of SNCC, and when somebody was arrested, say Mary Lane is in the jail in Greenwood, Mississippi, well, you know someone would call for Chicago, and this so and so would call from there and you have to have some kind of response outside because they think that they don’t have to be beholden to anybody, even in their own community. But, at least if somebody outside their community is seeing it, and they are aware that they’re seeing it, it may help. But I don’t know what kind of network you can do to use that. But I certainly would get on the email. I would call. I would do whatever.

Rucker: Thank you so much. Now, we just have two golden minutes before I want to say some other things. But we have seven minutes before we’re going to wrap up. But this question came from one of our participants, and I want to ask this question, too: How can those of us in places like Chicago or here in D.C. organize to support our colleagues in Texas or Florida, or other places where teaching history is being suppressed and criminalized?

Cox: I’m not sure of all its responsibilities, but one of the things that Judy just mentioned is having a central location where people can talk about ideas, but also begin to do the supporting and networking that is really important. Things might seem that they may be going around and they’re not to that point that I have to deal with this problem, but it seems there’s this bigger problem that always exists. One of the things — and I hate to say this at the end so that it may freak people out at least a little more — is that we are really fighting to determine whether public education can exist in this country. At the end of the day, that’s what the money people want to do. A number of things. So the fight is really a big fight and it’s not just the fight that you have, and it’s going to be a fight for a lifetime for those who you believe in education.

Rucker: Thank you all so much. I think that’s a powerful place for us to pause. I want to say thank you, thank you, thank you, thank you to Courtland, to Jennifer, to Judy, and to the folks who are here with us participating, our co-learners. We want your feedback on this session, both the content and the format. We put the link in the chat box. But before that evaluation please unmute yourself and or use the chat and share your thank you to our SNCC veterans. We’ll continue to keep the movement going. Please thank each other for your commitment to learning and teaching, and massive, massive shout-outs to our breakout facilitators and our ASL interpreters, Krystal and Tyriibah. Thank you. Thank you. Thank you.

We’re going send a follow-up email with resources that were referenced here today. Please go ahead and complete the evaluation. We are going to be playing “This Little Light of Mine” sung by Sam Cooke. Because we want to let this historical moment fuel us and not fool us, like Mariame Kaba reminds us, let’s let this radicalize us rather than lead us into despair. We got this, y’all.

Lawson: Thank you all so much. And thank you, Jessica. Thanks to the Zinn Education Project.

While this transcript was edited, there may be minor errors or typos — if you notice something you believe to be incorrect please contact us at zep@zinnedproject.org.

Audio

Listen to the recording of the session on these additional platforms.

Audiogram

Take a moment to listen to Courtland Cox on the importance of determination.

Resources

Many of the lessons, books, and other resources recommended by the presenters and participants.

Lessons

|

Teaching SNCC: The Organization at the Heart of the Civil Rights Revolution by Adam Sanchez Sharecroppers Challenge U.S. Apartheid: The Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party by Julian Hipkins III, Deborah Menkart, Sara Evers, and Jenice View Stepping into Selma: Voting Rights History and Legacy Today by Teaching for Change COINTELPRO: Teaching the FBI’s War on the Black Freedom Movement by Ursula Wolfe-Rocca What Would You Do? Students Grapple with Risks Faced by Voting Rights Activists by Cristina Tosto |

Projects

|

|

All three SNCC presenters are on the board of the SNCC Legacy Project, which collects and analyzes SNCC’s work from the inside out. It is engaged in long-term collaborations to further SNCC’s legacy and carry movement work forward. Also check out the Freedom Schools Movement. The SNCC Digital Gateway offers profiles, stories, a timeline, map, and much more. It focuses on southwest Georgia, Mississippi, and the Alabama Black Belt as geographic locations central to SNCC’s voting rights organizing. |

Books

Films

|

Eyes on the Prize: America’s Civil Rights Years, 1954–1985, produced by Henry Hampton Freedom Song, written, directed, and produced by Phil Alden Robinson Lowndes County and the Road to Black Power, directed by Sam Pollard and Geeta Gandbhir |

Articles and Primary Documents

|

‘Is This America?’: Sharecroppers Challenged Mississippi Apartheid, LBJ, and the Nation by Julian Hipkins III and Deborah Menkart Lowndes County and the Voting Rights Act by Hasan Kwame Jeffries Negroes in American History: A Freedom Primer by Bobbi and Frank Cieciorka (The Student Voice, Inc.) The Voting Rights Act: Ten Things You Should Know by Emilye Crosby and Judy Richardson “The fascists can’t stop us!” — Judy Richardson at Teach Truth Rally |

This Day In History

The dates below come from our This Day in History collection, which contains hundreds of entries all searchable by date, state, theme, and keywords.

|

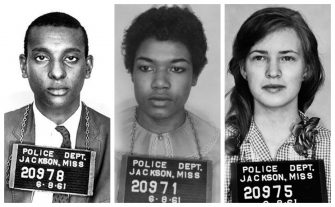

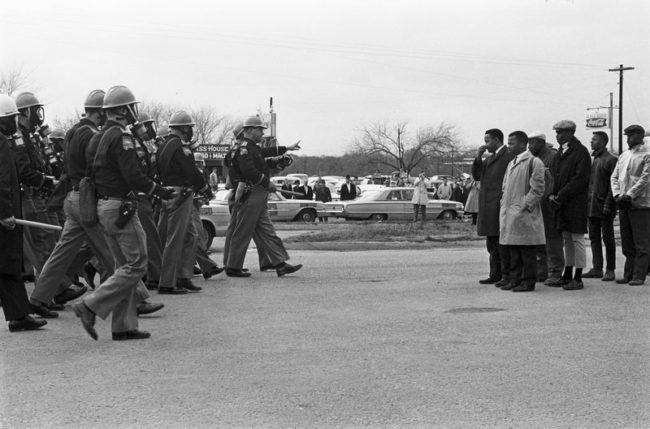

April 15, 1960: Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee Founding Feb. 6, 1961: “Jail, No Bail” in Rock Hill, South Carolina Sit-Ins June 8, 1961: Freedom Riders Arrested Nov. 17, 1961: Albany Movement Jan. 22, 1964: Freedom Day in Hattiesburg Aug. 8, 1964: Freedom Schools Convention Aug. 22, 1964: Sharecroppers Demand Delivery of Full Suffrage in the U.S. Jan. 4, 1965: Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party Challenges Congress March 7, 1965: Bloody Sunday March 23, 1965: Selma to Montgomery March Continues April 1, 1965: Blackwell v. Issaquena Board of Education Jan. 3, 1966: Sammy Younge Jr. Murdered June 6, 1966: James Meredith and the March Against Fear June 1, 1968: Founding of Drum and Spear Bookstore |

Participant Reflections

With more than 240 attendees present, the conversation and chat were lively, engaging, and full of history, teaching ideas, and more. Here are more comments that participants shared in their end-of-session evaluations.

What was the most important thing (story, idea) you learned today?

How these young people had the courage to assemble and fight against the system is such an important concept to pass along to our students today.

All of it! But felt inspired and fired up by the SNCC veterans, their storytelling and analyses. I could listen to them all day.

How vital the women were in SNCC and in the movement.

It was so valuable and such a privilege to hear from the original SNCC people. How amazing. I am taken by the Freedom Schools movement and need to know more!

It takes more than bravery to do this work and the work of SNCC. It takes determination. So, to keep this work going, we need more than schools. We need to create a community to prevent those in power from upholding structural racism.

The importance of long-term organizing over demonstrations.

The community should play a huge part in protecting teachers and education. It is still my role and responsibility to teach and educate our youth.

Just considering how young SNCC members were encourages me to reinforce this with the high school and college students I teach.

It can’t just happen in the classroom. “The organizing has to be bigger than the classroom you’re in,” said Courtland Cox.

The importance of knowing and remembering the names of individuals (say their names). The fact that we can — and need to — organize to support our colleagues who are being suppressed.

I love learning new stories that can be models for my students and empower them.

For me the confirmation that it is time for us to restart Freedom Schools in my community!

It was really the breakout rooms, the comments, and the resource sharing. Not feeling alone is so important. And of course, our SNCC elders are amazing. Thank you!

What will you do with what you learned?

I will be using the role play about SNCC in my 8th grade history course during the Civil Rights Movement unit. I will also show them the screenshot of me on Zoom with the SNCC veterans!

My colleague and I are talking about integrating this into a project-based learning assignment for a whole cohort of students.

I’m excited to look through the SNCC resources to find some lessons to better teach about Ella Baker and the Civil Rights Movement to my third graders. Excited to explore the primary sources too.

Teach about economic justice and use SNCC Digital Gateway.

I can’t wait to use more personal stories and the digital website in my classroom.

Keep looking for “colleague comrades” to stay supported in this difficult work.

I will share this information with teacher candidates and encourage them to continue their education about SNCC, organizing, and hidden history.

I am going to suggest we follow up our Teaching for Black Lives focus with the Negroes in American History: A Freedom Primer book.

When I teach U.S. History again, I will definitely use the SNCC digital resource. Now I will make sure that my Ancient History content is accessible (like the primer) and that I encourage students to question and act (never too young).

I will incorporate resources into lessons with my pre-service teacher social studies students, and I will be involved in organizing to support teachers. Looking into that tomorrow!

Going to explore some of the resources shared and will use those primary resources and connect to what we learn — in first grade. Truth to power!!

I am coordinating the development of an Ethnic Studies program, so 1) get these SNCC resources into that curriculum, and 2) work with like-minded colleagues to update our history courses to be more inclusive.

I will be looking at and using ALL of the resources that were mentioned and put in the chat. I can’t wait to use the Zinn Ed Project lessons.

Presenters

Courtland Cox became a member of NAG and the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) while a Howard University student. He worked with SNCC in Mississippi and Lowndes County, Alabama, was the program secretary for SNCC in 1962, and was the SNCC representative to the War Crimes Tribunal organized by Bertram Russell. In 1963 he served as the SNCC representative on the Steering Committee for the March on Washington. In 1973, Cox served as the Secretary General of the Sixth Pan-African Congress and international meeting of African people in Tanzania. He co-owned and managed the Drum and Spear Bookstore and Press. Cox went on to be a leader and advisor in D.C. government and continues as a strategic advisor with national civil rights organizations. He is the chair of the SNCC Legacy Project. Read more.

Jennifer Lawson first marched for civil rights as a teenager in 1963. She attended Tuskegee University and left to work full-time with SNCC in Lowndes County, Alabama. She served as SNCC’s deputy director for an adult education program in Mississippi before relocating to Washington, D.C. where she worked as art director for the Drum and Spear Bookstore and Press. She later became an executive and producer in public television where she served as head of PBS programming. Lawson noted, “I came to filmmaking because I also worked in adult literacy. And I felt after my time in SNCC, I felt that it was really important for us to tell our own story, not to wait for anybody else to tell our story but to tell our own.” Hear an interview with Lawson on History Makers. Read more.

Judy Richardson was on the staff of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) in Georgia, Mississippi, and Alabama (1963-66) and ran the office for Julian Bond’s successful first campaign for the Georgia House of Representatives. Her SNCC involvement has always been a strong influence in both her filmmaking and her education work on production of the award-winning 14-hour PBS series Eyes on the Prize, PBS’ Malcolm X: Make It Plain, and all the videos for the Little Rock 9 National Park Service Visitor Center). Richardson was a co-founder of Drum & Spear Bookstore and children’s of Drum & Spear Press. She co-edited Hands on the Freedom Plow: Personal Accounts by Women in SNCC, was co-director of two NEH Teacher Institutes, and is currently directing the Frederick Douglass visitor center film for the National Park Service. Read more.

Jessica Rucker is a graduate student in the Department of American Studies at the University of Maryland, College Park, and a Prentiss Charney Fellow. Prior to her graduate work, she was a high school teacher in Washington, D.C.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn