Too often, textbooks present famines as natural phenomena. They are not. As Sudan, Congo, and Gaza move closer toward famine, it is not hard to see its causes. In addressing Gaza, the European Union foreign policy chief Josep Borrell said recently:

This is a humanitarian crisis, which is not a natural disaster. It’s not a flood. It’s not an earthquake. It’s man-made. And when we look for alternative ways of providing support, by sea or by air, we have to [remember] that we have to do it because the natural way of providing support, through roads, is being closed, artificially closed, and starvation is being used as a war arm. And when we condemn this happening in Ukraine, we have to use the same words for what’s happening in Gaza.

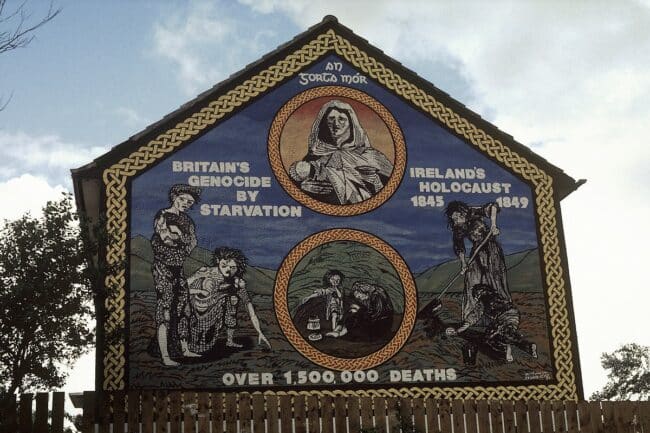

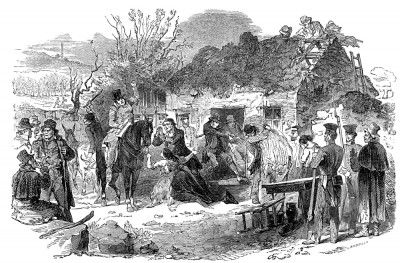

Of course, the most famous famine is the so-called “Potato Famine” in Ireland. For better or worse, St. Patrick’s Day is that brief period during the year when people pay attention to all things Irish. It is a good time to revisit Ireland’s Great Famine and the refugee exodus it unleashed — and to recognize what it holds in common with other famines, past and present.

Studying the so-called Potato Famine can help students see that this was no natural disaster, it was the product of structural violence. As Bill Bigelow writes in his “If We Knew Our History” column, “The Real Irish American Story Not Taught in Schools,”

During the first winter of famine, 1846–47, as perhaps 400,000 Irish peasants starved, landlords exported 17 million pounds sterling worth of grain, cattle, pigs, flour, eggs, and poultry — food that could have prevented those deaths.

The shape of the wound of famine was British colonialism and the capitalist system, which prized profit over the Irish poor. See our lesson, “Hunger on Trial,” which brings this insight to life in the classroom — and helps students consider the roots of today’s unnatural disasters.

Teaching Palestine-Israel: Food Sovereignty and Israel’s War on Gaza

This infographic from Visualizing Palestine explores various ways that Israeli policies of settler colonialism and apartheid deny Palestinian food sovereignty.

During the Nakba in 1948, Palestinian refugees lost some 4.6 million dunums (about 18 million acres) of farmland, which the Israeli state quickly appropriated for Jewish-only agricultural settlements. The ongoing Nakba continues to take a heavy toll on farmers, fishers, and pastoralists across historic Palestine.

Find more classroom resources including lessons, podcasts, films, and articles to teach about Palestine-Israel.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn