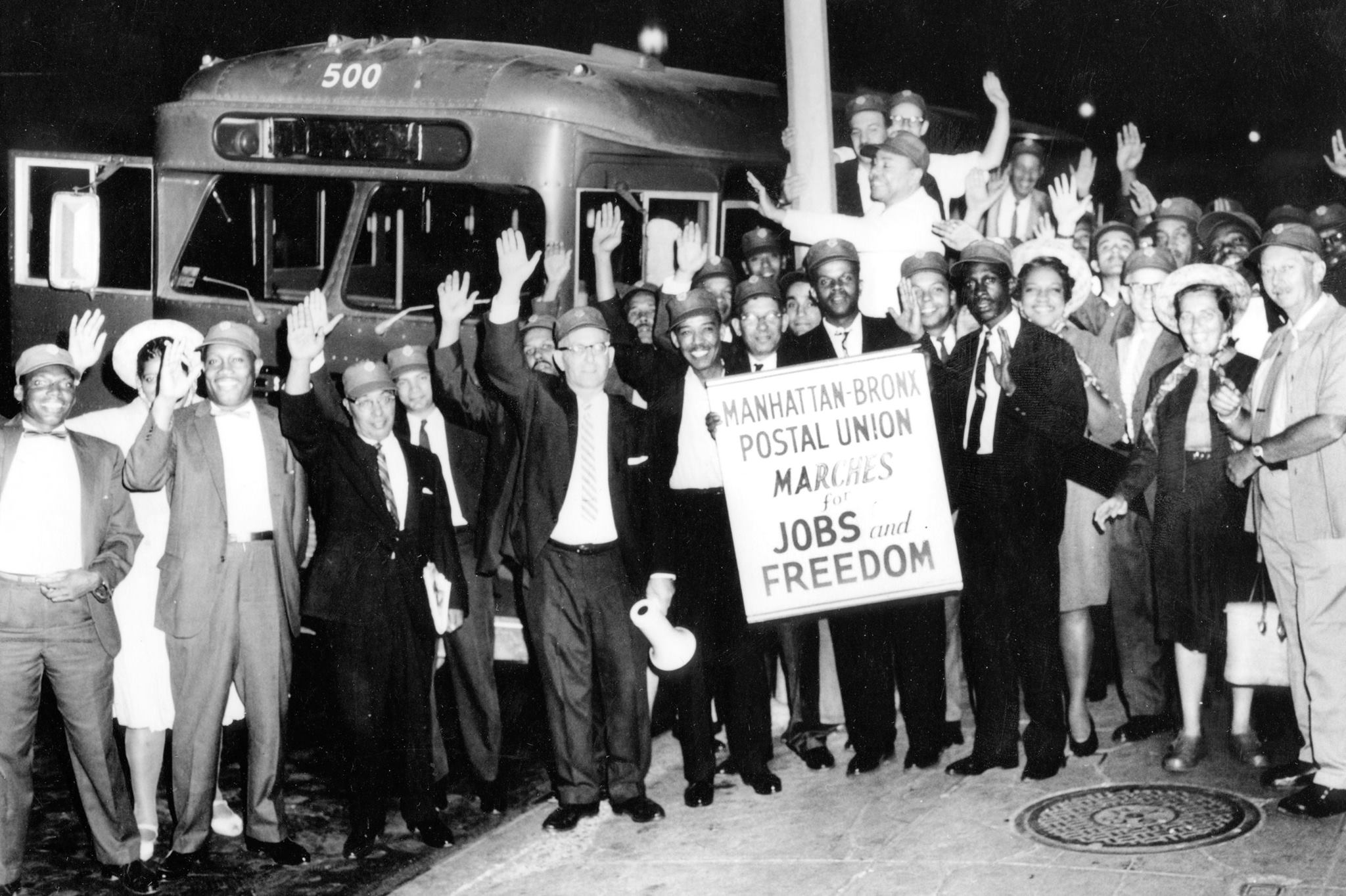

Historians initially studied the freedom movement by looking not at the 250,000 marchers, but at the leaders on the platform high above the crowd gathered at the Lincoln Memorial. Rendered invisible were the many delegations from the West Coast, the East Coast, and the Midwest — men and women who converged on Washington with banners and placards that identified issues of their locales. — Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham in Freedom North

To introduce students to a people’s history of the March on Washington, high school teachers Jessica Lovaas and Adam Sanchez wrote a lesson that begins not on the Mall, but instead in eight cities where organizers prepare to travel to the nation’s capital in August of 1963.

Their Rethinking Schools lesson introduces students to local struggles in Los Angeles; Birmingham; Brooklyn; Detroit; Cambridge, Maryland; McComb, Mississippi; Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; and Albany, Georgia.

The challenges and victories in these cities shaped the demands of organizers for the March, including addressing police brutality, housing discrimination, school segregation, labor rights, voting rights, quality education, and more.

Lovaas and Sanchez wrote:

We wanted students to think deeply and personally about what motivated individuals, old and young alike, to travel, sometimes thousands of miles, to attend.

One of the best parts about studying the March on Washington from the perspective of the marchers is it allows teachers and students to investigate their local history, as people came to the March from all over the country.

Black Labor Rights

March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom

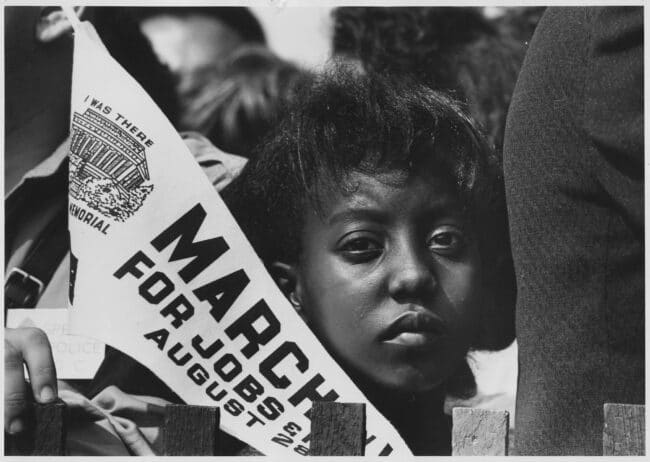

Photograph of a Young Woman at the Civil Rights March on Washington, D.C. with a Banner, 08/28/1963. Source: National Archives

By Bill Fletcher Jr.

While Dr. Martin Luther King was a major player, the March on Washington did not begin as a classic civil rights march and was not initiated by him. There is one constituency that can legitimately claim the legacy of the march — one that has been eclipsed in both history as well as in much of the lead-up to the annual commemorations: Black labor.

More Than a Dream

New Book for Young Readers

Without diminishing the words of Dr. Martin Luther King at the March on Washington, More Than a Dream by Yohuru Williams and Michael G. Long looks at the March through a wider lens. The authors use Black newspaper reports as a primary resource, recognizing the overlooked work of socialist organizers and Black women protesters, and repositioning this momentous day as radical in its roots, methods, demands, and results. [Publisher’s description.]

Without diminishing the words of Dr. Martin Luther King at the March on Washington, More Than a Dream by Yohuru Williams and Michael G. Long looks at the March through a wider lens. The authors use Black newspaper reports as a primary resource, recognizing the overlooked work of socialist organizers and Black women protesters, and repositioning this momentous day as radical in its roots, methods, demands, and results. [Publisher’s description.]

Coherent, compellingly passionate, rich in sometimes-startling and consistently well-founded insights. ― Kirkus Reviews, starred review

First Hand Accounts from SNCC Veterans

The original speech, to be delivered by the SNCC chairperson (John Lewis) at the March on Washington, accused the federal government of “conspiracy” with the South’s white supremacist governments. And it threatened to launch “our own scorched earth policy and burn Jim Crow to the ground ― nonviolently.”

As explained at SNCCDigital.org, “Fueling SNCC’s words was the fact that the Washington establishment, especially the Department of Justice, had failed to protect Black communities in the South and ignored discrimination across the country.”

We invite you to hear first hand about the events at the March on Washington and local organizing from three SNCC veterans, on Monday, September 11 in a session called Teaching in Dangerous Times: Lessons from SNCC.

A People’s History of the Black Working Class

Conversation with Blair L. M. Kelley

The central role of Black labor is missing from most March on Washington commemorations. African Americans are absent from most media references to “the working class.”

Join us to learn how to correct those misrepresentations. Historian Blair L. M. Kelley will discuss her new book, Black Folk: The Roots of the Black Working Class, which uses personal narratives to highlight the community and networks of resistance that Black laborers built in the face of racism and segregation.

A powerful counter to the assumption that the term working class refers only to whites. Rather, she argues convincingly, Black workers have been the nation’s “most active, most engaged, most informed, and most impassioned working class.” ― Kirkus Reviews

Black Folk is at once a love song, a blues, and an epic account of the Black working class in the United States. ― Robin D. G. Kelley

This class is part of the Zinn Education Project’s Teach the Black Freedom Struggle online series with people’s historians. Participants learn from the scholar in conversation with a teacher and meet in small groups for discussion. One participant noted,

This is one of the best professional developments I have ever been to, hands-down. I am so grateful. This series gives me hope in this difficult time.

This Week in People’s History

Aug. 21, 1939: African Americans Arrested for Going to Public Library

Five African Americans staged a sit-in at the Alexandria public library that had a “whites only” policy. African Americans paid taxes that funded the library.

The police, instead of defending the right of local residents to check out books, arrested them.

We may need to use these Civil Rights Movement tactics again as school libraries are closed by well-funded and highly orchestrated white supremacist and anti-LGBTQ censorship policies.

| More Library Sit-Ins | More #TDIH |

Other upcoming days in people’s history include the March on Washington, a milestone in the centuries-long Black Freedom Struggle. The date of the march symbolizes that long history — it was held on the 100th anniversary year of the Emancipation Proclamation (1863) and eight years to the day after 14-year-old Emmett Till was lynched in Mississippi (1955).

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn