On January 10, 1854, a judge in Norfolk, Virginia, sentenced a white woman, Margaret Douglass, to one month in jail for teaching free Black children to read. The jury had recommended a $1 fine, but Circuit Court Judge Richard H. Baker said he imposed the jail term to set an example for others who could undermine “peace” in Virginia with such “manifestly mischievous” opinions or performing similar activities. He also chided Douglass, who was a home-based vest-maker, for representing herself instead of hiring an attorney.

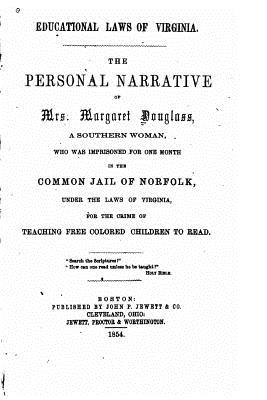

Educational Laws of Virginia, the Personal Narrative of Mrs. Margaret Douglass. Source: Bookshop.org

Resettling in Philadelphia soon after completing her jail term, Douglass published a 65-page memoir, Personal Narrative of Mrs. Margaret Douglass, a Southern Woman Who Was Imprisoned for One Month in the Common Jail of Norfolk, Under the Laws of Virginia, for the Crime of Teaching Free Colored Children to Read. While Douglass insisted in her trial and book that she was not an abolitionist, she denounced both the Virginia law that prohibited teaching literacy to free African Americans and the judge as short-sighted, disgraceful and cruel, and the hypocrisy and cowardice of Norfolk elites who taught Black children in Sunday schools but would not publicly acknowledge their actions. Douglass’ book also provided insights into white fear of Black literacy and beliefs about white supremacy, some of which Douglass also held.

Douglass concludes her book with a condemnation of the “grand secret” of the pervasiveness of Southern white men sexually forcing themselves upon powerless enslaved Black women and calls upon her “Southern sisters” to stop tolerating “this damning curse.”

In her memoir, Douglass details how she and her teenaged daughter, Rosa, organized a small private school for 20 to 25 free Black children based on friendship, religious beliefs, and charity. Douglass wrote that she and Rosa operated the school — with Rosa leading most of the classes — for about a year before someone reported them to the mayor and police. Douglass said she was not trying to hide the activity because she thought it was only illegal to teach enslaved Blacks in Virginia, while it was okay to give literacy lessons to free African Americans.

Two policemen raided her house on May 9, 1853, and marched Margaret and Rosa Douglass, along with their students, to see Norfolk Mayor Simon S. Stubbs. Douglass wrote:

Will my readers please imagine, for an instant, a crowd of little children, walking two and two, preceded and followed by two stout men, each with a great club in his hands? It reminded me of a flock of little lambs going to the slaughter.

The mayor let everyone go with just a warning after Douglass promised to immediately disband the school. However, Margaret and Rosa Douglass received a grand jury indictment on July 13 and a trial was set for November. In her defense, Douglass called only three witnesses, all from an affluent church where free Black children were being taught to read with the same books used at her school. Two of the witnesses denied knowledge and the third, a lawyer named “Mr. Sharp,” blamed female members of the congregation, saying, “The ladies had all to do with that!”

Incensed, Douglass exclaimed

Oh, brave Mr. Sharp. You will henceforth be remembered in Norfolk as having crept under the ladies’ aprons in order to shelter yourself from the eye of the insulted law.

Margaret Douglass. Source: Internet Archive

It took three days for the jury to render the guilty verdict and recommend the $1 fine. Judge Baker then set Jan. 10, 1854, for formal sentencing and surprised everyone when he sent Douglass to jail for one month, according to Douglass.

Baker cited two main reasons for laws that prohibited teaching reading to African Americans. One was the potential of more slave revolts, such as the 1831 rebellion led by Nat Turner in Southampton County, Virginia; the other was to counter the activities of “Northern fanatics,” who clog the mail with “abolition pamphlets and inflammatory documents, to be distributed among our Southern negroes to induce them to cut our throats.”

In her memoir, Douglass asserted counter reasons, including that literate Black people would read the bible and better understand the brutal nature of the sexual “sin of their masters” and come away “with a deeper horror of this great wickedness.” This awareness, Douglass maintained, had the potential to cause more Black discontent and rebellion against “these Southern sultans.”

This story was prepared by Michael Knepler, who occasionally contributes #tdih entries to the Zinn Education Project.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn