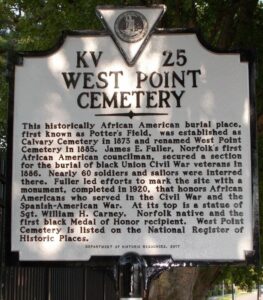

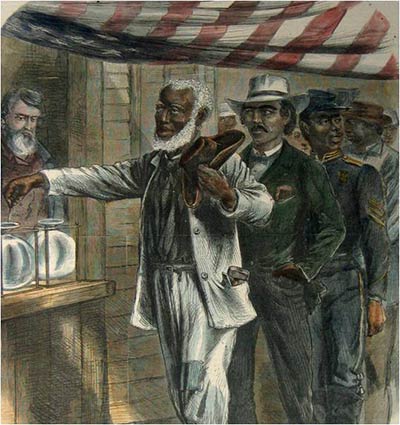

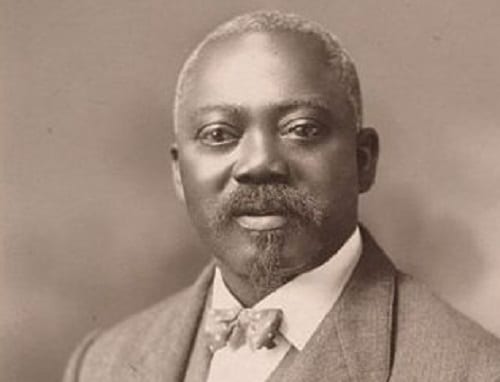

On March 30, 1886, James E. Fuller, a formerly enslaved person, a Civil War quartermaster of the First U.S. Colored Calvary and the first African American elected to the Norfolk Common Council in Virginia, persuaded fellow Reconstruction Era council members to dedicate a burial area for Black soldiers and sailors who fought to preserve the Union — a significant salute because Norfolk, although a Southern city, had been a fertile recruiting area for the federal military to enlist African Americans.

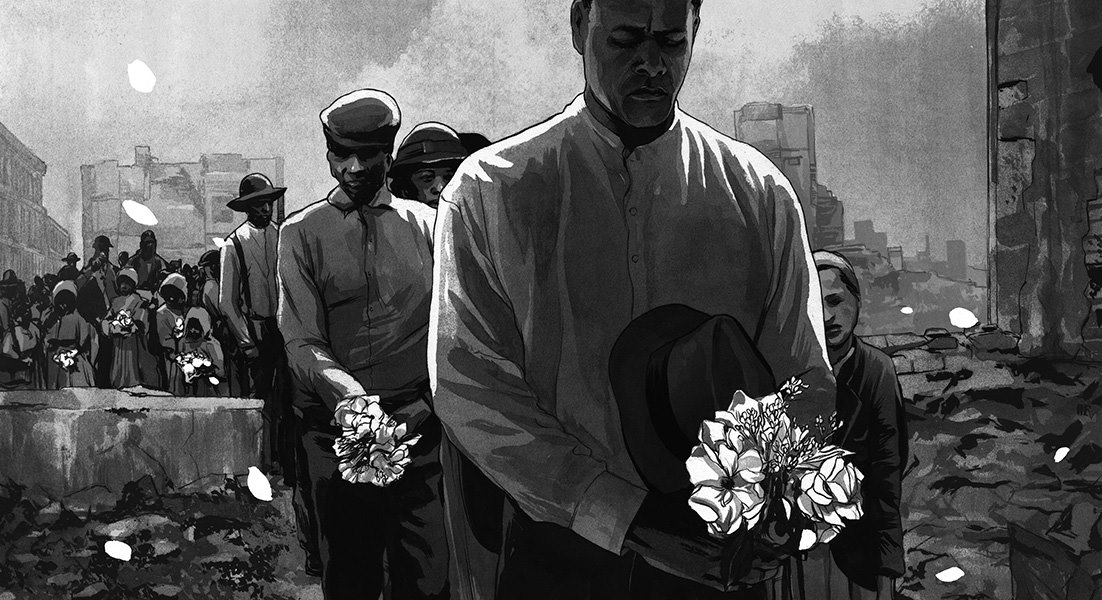

This began 34 years of patient but persistent efforts to crown the cemetery with a prominent monument — topped by a statue of an African American soldier — to commemorate the bravery of the Black troops. Grassroots activities included “bake sales, civil and social group meetings, dinners, raffles and concerts to raise the money,” according to historian Dr. Cassandra Newby-Alexander, dean of Norfolk State University’s College of Liberal Arts.

Newby-Alexander described the monument as “a perpetual reminder of the blood that was proudly and willingly shed by African Americans to ensure that their descendants would not continue as enslaved people.”

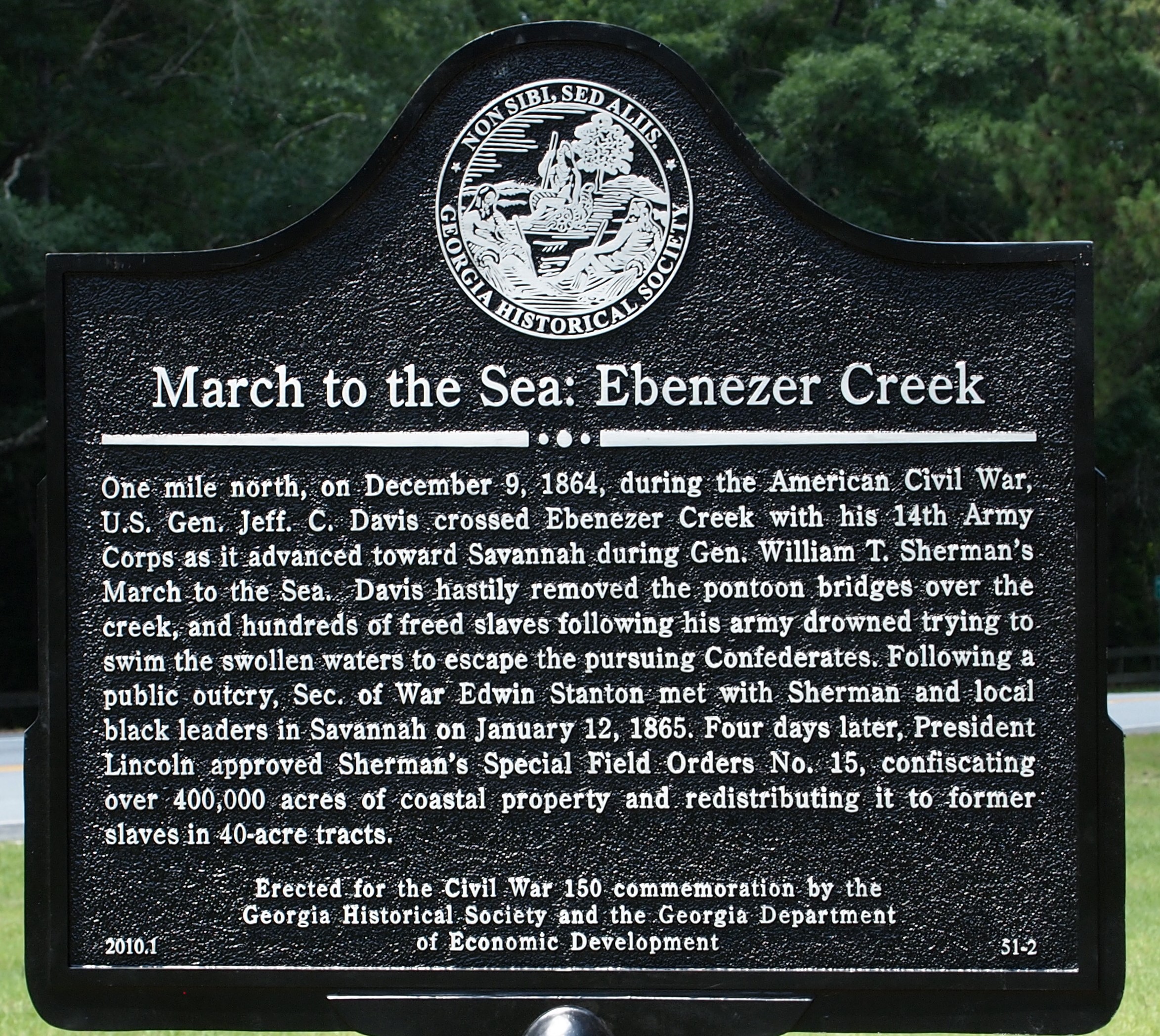

The historic cemetery, known as West Point because it lies on the western edge of the formerly all-white Elmwood Cemetery, contains 58 graves of Union soldiers and sailors, among other African Americans buried on the 14 acres, according to historian Dr. Tommy L. Bogger, a professor emeritus at Norfolk State.

The steel-framed concrete and granite base of the eventual monument was installed in 1906. Fuller did not live to see its completion. He died in 1909 and was buried in West Point near a great sycamore tree. The memorial was finished in 1920, when it was topped with a detailed, life-sized bronze statue of a soldier modeled after real-life Sgt. William H. Carney Jr., whose battlefield heroics — wounded four times while saving the Union flag — were somewhat portrayed by actor Denzel Washington as fictionalized “Private Silas Trip” in the 1989 movie Glory.

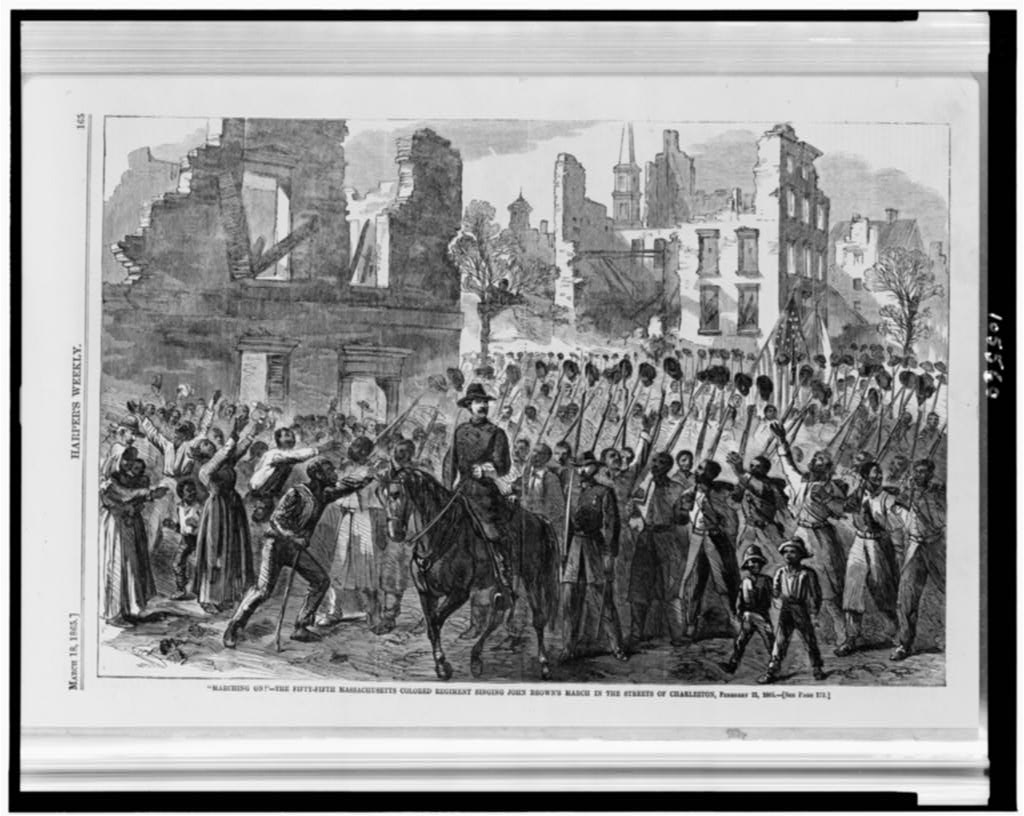

Carney had been born in the Norfolk area to an enslaved family that resettled in New Bedford, Massachusetts. There, on Feb. 17, 1863, he enlisted in the 54th Massachusetts Infantry, the Union’s first regiment of Black soldiers. He was the first African American to perform a battlefield action for which the prestigious Medal of Honor was awarded. However, he did not receive formal recognition until 1900.

West Point Cemetery statue commemorating Black soldiers during the Civil War. Source: Mykella Palmer-McCalla.

There are other bittersweet parts to the story of West Point Cemetery. It was developed along a swampy area as a potter’s field for paupers, and it continues to be partly separated from the once all-white Elmwood Cemetery by a 10-foot-high brick wall that runs for more than 800 feet — a relic of Jim Crow apartheid, even in death.

As historian Tommy Bogger noted in the nominating papers for West Point Cemetery’s inclusion on the National Register of Historic Places:

Even though the ten-foot high brick wall separating West Point from the white Elmwood Cemetery is a dramatic reminder of the Jim Crowism that Blacks experienced during the aftermath of Reconstruction, West Point allowed them to bury their dead with dignity. They also used the cemetery to gather for their annual Memorial Day observances, and they took casual strolls through the park-like setting in the warm weather months.

One of the plaques affixed to the monument proudly reads: “In the Memory of Our Heroes 1861-1865.”

The United States still needs to honor all African Americans who served in the Civil War with a Congressional Gold Medal, according to U.S. Sen. Cory Booker of New Jersey and non-voting Del. Eleanor Holmes Norton, who represents Washington, D.C. They are seeking bicameral legislation.

“Though often overlooked, 200,000 Black Americans fought to save the union during the Civil War, helping end the evil institution of slavery and ensuring the United States would endure,” Booker said.

Norton added:

Despite sacrificing life and limb, hundreds of thousands of African Americans who fought for the Union in the Civil War have largely been left out of the nation’s historical memory. . . This bill will help correct that wrong and give the descendants of those soldiers the recognition they deserve.

By Michael Knepler, who prepares occasional #tdih posts for the Zinn Education Project.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn