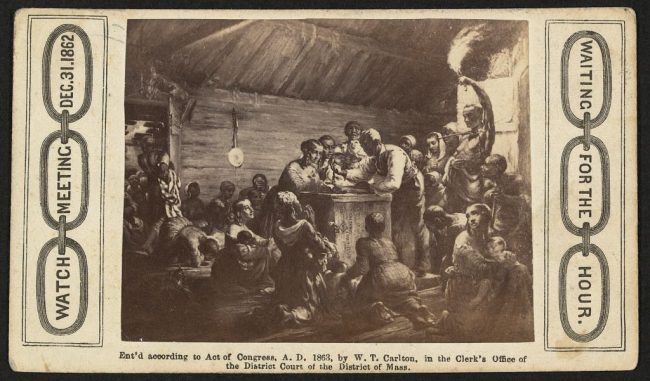

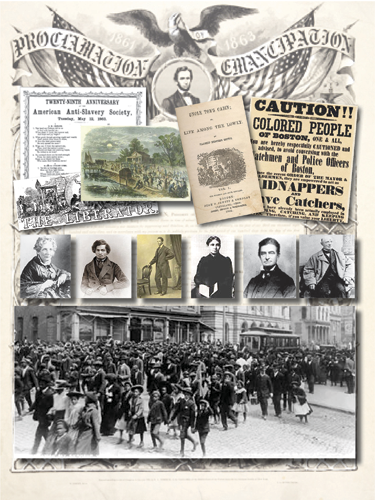

On Dec 31, 1862, African Americans across the United States, free and enslaved, in the North and South, held watch meetings for the Emancipation Proclamation that officially abolished slavery in the Confederate states. Issued by President Abraham Lincoln on September 22, the Proclamation did not take effect until January 1, 1863.

Bill Bigelow explains in “Rethinkin’ Lincoln on the 150th Birthday of the Emancipation Proclamation,”

Interestingly, despite the fact that the proclamation is mentioned in virtually every textbook, it is never printed in its entirety. Perhaps that’s because despite its lofty-sounding title, this is no stirring document of liberty and equality; in fact, it does not even criticize slavery. “Emancipation” is presented purely as a measure of military necessity. Lincoln offered freedom to enslaved people in those areas only “in rebellion against the United States.” It reads like a document written by a lawyer — one who happened to be a Commander in Chief — not an abolitionist. It even goes county by county listing areas where slavery would remain in force, “precisely as if this proclamation were not issued.” According to Eric Foner, the proclamation left more than 20 percent of enslaved people still in slavery — 800,000 out of 3.9 million.

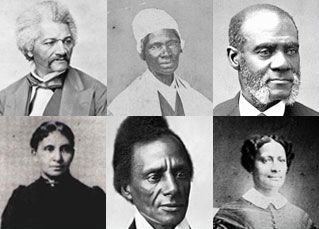

No doubt, the Emancipation Proclamation was a huge deal, and it was cheered by abolitionists and even those who remained enslaved. As the great African American abolitionist Frederick Douglass pointed out, Lincoln’s proclamation united “the cause of the slaves and the cause of the country.” Those opposed to slavery were determined to use the Emancipation Proclamation as an instrument to end slavery everywhere and forever — regardless of Lincoln’s more limited intent. Freedom would be won, not given. Continue reading.

It’s time to teach outside the textbook about the people’s history of the abolition movement.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn