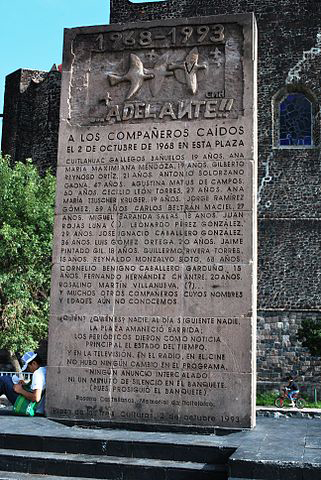

Monument at site of 1968 Mexico City Massacre.

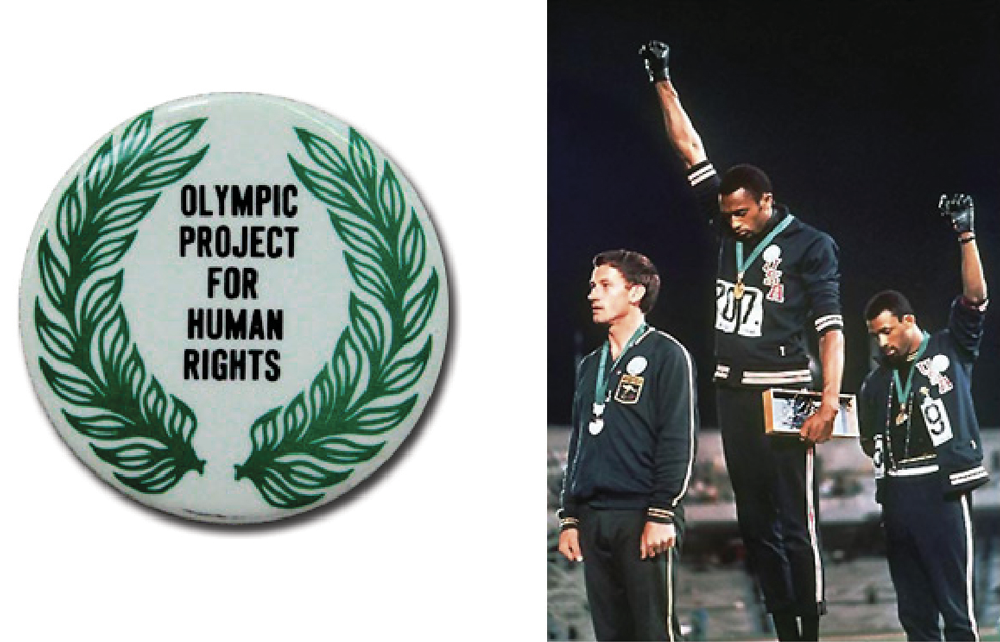

In 1968, students throughout the world challenged their governments’ policies and practices. Students organized demonstrations in Egypt, Italy, Yugoslavia, the United States, Uruguay, and France. Mexico was no exception. Students organized to protest the lack of true democracy in Mexico.

The political system had been dominated by one party, the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI), for decades. Every president of Mexico since 1929 had been from the same party. (This did not change until Vicente Fox and the National Action Party-PAN broke the cycle in the 2000 election.) Every effort students made to raise a voice of protest was met with repression.

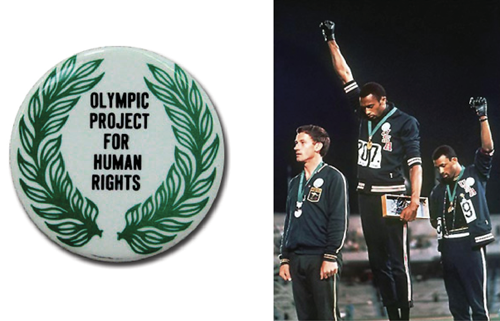

The Mexican student movement galvanized popular discontent, at least for a brief period of time. The students also gained worldwide attention and exposed vast contradictions in the government and other institutions. The Mexican government was threatened by the burgeoning democratic movement as the world’s gaze shifted to the upcoming Olympics in Mexico City. In an effort to silence the dissent, the police and army occupied the university campus.

The tension began in July, but the climax came on October 2, 1968, ten days before the Olympic games were to begin in Mexico City. On this date, the police and army fired on thousands of demonstrators. Hundreds were killed, thousands were beaten and jailed, and the government did its best to sweep the incident under the rug.

The tragic incident of October 1968 took place in the same location as the Spanish massacre of the Aztecs at Tlatelolco almost 500 years before.

Text by Octavio Madigan Ruiz, Amy Sanders, and Meredith Sommers.

Poem

Memory of Tlatelolco

by Rosario Castellanos

And who saw that brief, vivid flash of light?

Who is the one who kills?

Who are the ones who breathe their last; who die?

Who are the ones fleeing without their shoes?

Who are the ones belonging to the deep well of jails?

Who are the ones rotting in hospital?

Who are the ones struck dumb, forever, with horror?

Who? Who are the ones? Nobody. The next morning, nobody.

They found the square was swept clean. The front pages of the newspapers were full of the state of the weather. And on the television, on the radio, in the cinema, there was no change of programming, no special announcement. Not any meaningful silence in the midst of the banquet, because the banquet went on.

Don’t look for what isn’t there: traces, bodies, it’s all been given as an offering to a goddess, the Great Devourer of Excrement…

There are no official records.

Yet the fact is I can touch a wound.

In my memory it hurts, therefore it’s true.

I remember. We remember.

That’s our way of helping the very brave on so many a stained mind…

I remember.

Let’s all remember until justice becomes clear among us.

Rosario Castellanos (May 25, 1925 – August 7, 1974) was a Mexican poet and author. Throughout her life, she wrote about issues of cultural and gender oppression.

Related Resources

|

The Tlatelolco Massacre: U.S. Documents on Mexico and the Events of 1968 by Kate Doyle for the National Security Archive. Detailed report and primary documents here. |

|

Students Confront the Government: The Massacre at Tlatelolco. A lesson in the form of a “readers’ theater” from the book Many Faces of Mexico (Resource Center of the Americas, 1998). The narrative reading includes places to pause for discussion and a writing assignment. Primary source materials are used almost exclusively. Most of the documents, eyewitness accounts, and testimonies are from Massacre in Mexico by Elena Poniatowska. |

|

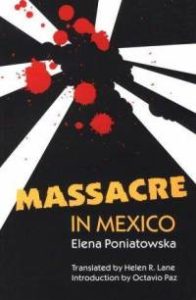

Massacre in Mexico by Elena Poniatowska, a journalist and author of testimonial literature. Her brother was killed during the riots of 1968. The publisher notes, “In this heartbreaking chronicle, Elena Poniatowska has assembled a montage of testimony drawn over a three-year period from eyewitness accounts by surviving students, parents, journalists, professors, priests, police, soldiers, and bystanders to re-create the chaotic optimism of the demonstrations, as well as the terror and shock of the massacre. Massacre in Mexico remains a critical source for examining the collective consciousness of Mexico.” |

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn