Here is a synopsis of South Carolina testimonies at the hearings in July, 1871. Source: Library of Congress

On July 7, 1871, Elias Thomson, an African American who lived in Spartanburg, South Carolina, bravely shared testimony detailing violence inflicted against him because he voted for the Republican ticket in the local election.

Three months prior, Congress had passed the third in a series of laws to protect the constitutional rights of African Americans from the constant threat and reality of white supremacist violence, intimidation, and fraud. This Klan Enforcement Act made some of those offenses federal crimes, strengthening an ongoing congressional investigation into the Ku Klux Klan’s terror campaigns. The investigation involved a series of hearings conducted by a joint select committee with crucial testimonies from over 500 witnesses, including Thomson.

As Kidada E. Williams explains in her introduction to They Left Great Marks on Me: African American Testimonies of Racial Violence from Emancipation to World War I,

Many testifiers . . . shared a “duty to relate” what Black people felt and knew about the horrors of this violence and what they believed their fellow citizens, state and federal officials, and the press should know.

In feeling a responsibility to relate their individual and collective experiences of violence, African Americans embraced what Dwight McBride calls the “politics of experience,” whereby people who testified presented themselves not only as victims and witnesses but also as experts on violence and representatives of their people.

. . . These victims’ and witnesses’ subsequent refusal to endure violence silently constitutes an underappreciated form of resistance to white supremacy.

Testimony

Here are excerpts from the brave testimony of Elias Thomson:

There came a parcel of gentlemen to my house one night — or men. They went up to the door and ran against it . . . hallooed to me, “Open the door, quick, quick, quick.” I threw the door open immediately — right wide open. . . . I said, “Come in, gentlemen.” One of them says, “Do we look like gentlemen?” I says, ”You look like men of some description; walk in.”

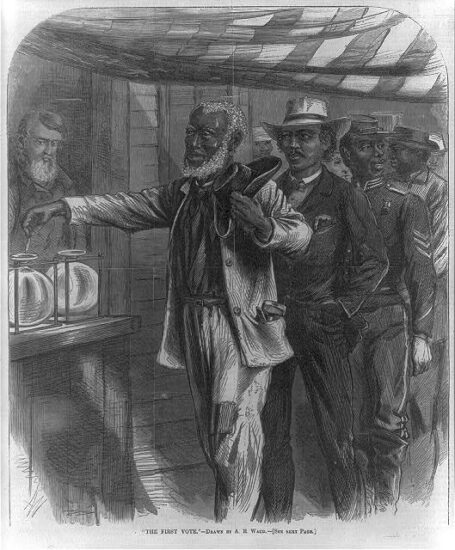

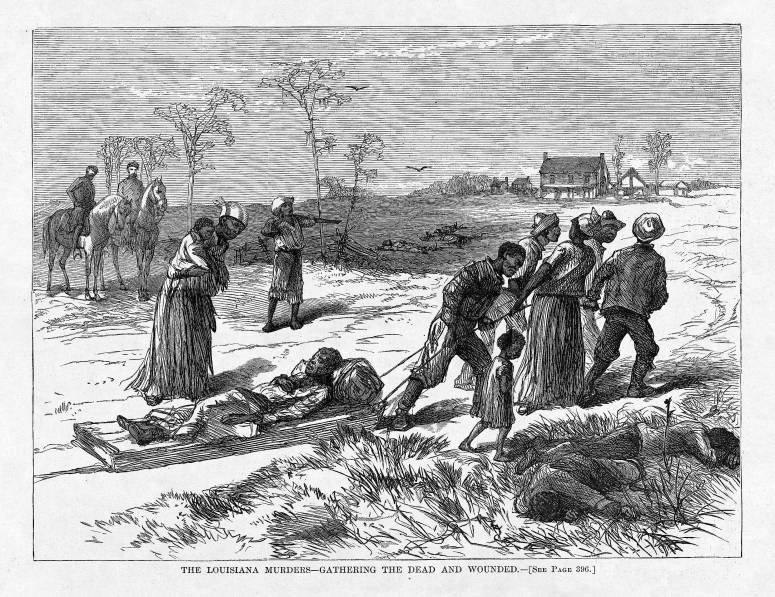

African Americans who exercised their right to vote often faced violent white supremacist attacks. Source: Library of Congress

One says, “Come out here; are you ready to die?” I told him I was not prepared to die. “Well,” said he, “your time is short; commence praying.”

One of them held a pistol, to my head and said, “Get down and pray.” I was on the steps, with one foot on the ground. They led me off to a pine tree. There was three or four of them behind me, it appeared, and one on each side, and one in front. The gentleman who questioned me was the only man I could see. All the time I could not see the others. Every time I could get to look around they would touch me with a pistol on the other side. They would just touch me on the side of the head with a pistol, so I had to keep my head square in front.

The next question was, “Who did you vote for?” I told them I voted for Mr. Turner — Claudius Turner [on the Republican ticket], a gentleman in the neighborhood. They said, “What did you vote for him for?” I said, “I thought a good deal of him; he was a neighbor.” I told them I disremembered who was on the ticket besides, but they had several, and I voted the ticket. “What did you do that for?” they said.

Says I, “Because I thought it was right.” They said, “You thought it was right ? It was right wrong.” I said, “I never do anything hardly if I think it is wrong; if it was wrong I did not know it. That was my opinion at the time, and I thought every man ought to vote according to his notions.”

He said, “If you had taken the advice of your friends you would have been better off.” I told him I had. Says I, “You may be a friend to me, but I can’t tell who you are.” Says he, “Can’t you recognize anybody here?” I told him I could not; “In the condition you are in now I can’t tell who you are.”

. . . Old man,” says one, “have you got a rope here, or plow-line, or something of the sort ?” I told him, “Yes; I had one hanging on the crib.” He said, “Let us have it.” One of them says, “String him up to this pine tree, and we will get all out of him. . . .”

Widespread Terror and Violence

This story and countless others are evidence of the extreme violence perpetrated against African Americans and white allies for voting, owning land, demanding fair pay, and more. They are also stories of bravery and solidarity in a movement to end white supremacist terror and hold its perpetrators accountable. In the early 1870s, many Klansmen were tried and prosecuted in federal court with predominantly Black juries. The first generation of the Klan was destroyed, but other white terror groups would expand throughout the decade and the Klan would resurge in the 1910s.

School Curriculum on Reconstruction

As noted in our report, Erasing the Black Freedom Struggle: How State Standards Fail to Teach the Truth About Reconstruction, it is critical that students learn how “white supremacists used terrorism and fraud to stall and reverse many of the significant advances made by Black people and their allies during Reconstruction, and shaped the politics, policies, and outcomes of the era.”

And yet, we found that state standards “rarely name or contend with white supremacy or white terror” or emphasize the legacies of Reconstruction and its dismantling. 150 years after its passage, the Klan Enforcement Act would be invoked in the aftermath of Jan. 6, 2021, in efforts to hold Capitol insurrectionists accountable for conspiring against the will of the people and violating constitutional rights.

Learn more about these connections and the importance of teaching Reconstruction from the resources below.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn