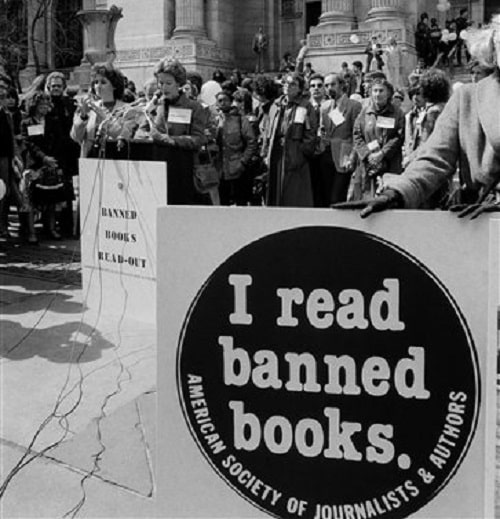

A crowd holds a rally in New York in 1982 protesting the censorship of school and public libraries of certain books under pressure from right-wing religious groups. AP photo by Carlos Rene Perez. Source: Free Speech Center at Middle Tennessee State University

Fed up with books being banned by the school administration, on January 4, 1977, students at Island Trees High School in Long Island, New York, along with the New York Civil Liberties Union, sued the school board for this unconstitutional censorship. Led by Island Trees student council president Steven Pico, the case went all the way up to the Supreme Court, Board of Education, Island Trees Union Free School District No. 26 v. Pico (1982).

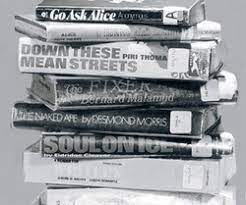

In 1975, members of the Island Trees school board attended a conference sponsored by a conservative education group; following the conference, the board attempted to ban several books from schools in their district. The books that the board found to be “anti-American, anti-Christian, anti-Sem[i]tic and just plain filthy” were:

- Slaughterhouse-Five by Kurt Vonnegut, Jr.

- The Naked Ape by Desmond Morris

- Down These Mean Streets by Piri Thomas

- Best Short Stories of Negro Writers edited by Langston Hughes

- Go Ask Alice anonymous

- Laughing Boy by Oliver LaFarge

- Black Boy by Richard Wright

- A Hero Ain’t Nothin’ but a Sandwich by Alice Childress

- Soul on Ice by Eldridge Cleaver

- A Reader for Writers, edited by Jerome Archer

- The Fixer by Bernard Malamud

As Anthony Aycock wrote for the Washington Post:

After an initial burst of media attention, the plaintiffs returned to being students, leaving the legal work to the lawyers. In 1979, the district court ruled in favor of the school board. It reasoned that while “removal of such books from a school library may, indeed in this court’s view does, reflect a misguided educational philosophy, it does not constitute a sharp and direct infringement of any first amendment right.” An appellate court reversed that decision in 1980 and remanded the case back to district court, prompting the Supreme Court to step in.

In June 1982, the court ruled 5-4 in the students’ favor. In his opinion, Justice William J. Brennan Jr. wrote that while “local school boards have a substantial legitimate role to play in the determination of school library content,” those boards’ authority “must be exercised in a manner that comports with the transcendent imperatives of the First Amendment.” In other words, school officials can’t ditch books just because they don’t like them. Continue reading.

In a 2022 interview with CNN’s Nicole Chavez, former plaintiff and Island Trees student council president Steven Pico said:

I think today students are much more sophisticated. They have more knowledge about their rights as citizens. I actually have much more hope today that these battles are going to be fought and won. I know there are young people out there right now who are forming book clubs, groups where they’re going to actually read banned books and decide for themselves. I know there’s young people standing up, fighting these attempts at book censorship and that’s really encouraging because that did not happen when I was in school.

Most students were just simply unaware of their rights but today, young people are acutely aware of their rights. I’m really proud of them. I know that they’re not going to just sit back and take this. Continue reading.

Additional Resources

He Took His School to the Supreme Court in the 1980s for Pulling ‘Objectionable’ Books. Here’s His Message to Young People by Nicole Chavez (CNN)

The Largely Forgotten Book Ban Case That Went Up to the Supreme Court by Anthony Aycock (The Washington Post)

Board of Education, Island Trees Union Free School District v. Pico (1982) by Anuj C. Desai (Free Speech Center at Middle Tennessee State University)

Stories of sit-ins at public libraries.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn