By E. R. Bills

The 1910 Slocum Massacre in East Texas officially saw between eight and 22 African Americans killed, and evidence suggests casualties were 10 times these amounts. Yet the massacre has become a dirty Lone Star secret, remarkable more for the inattention it has received than for its remembrance.

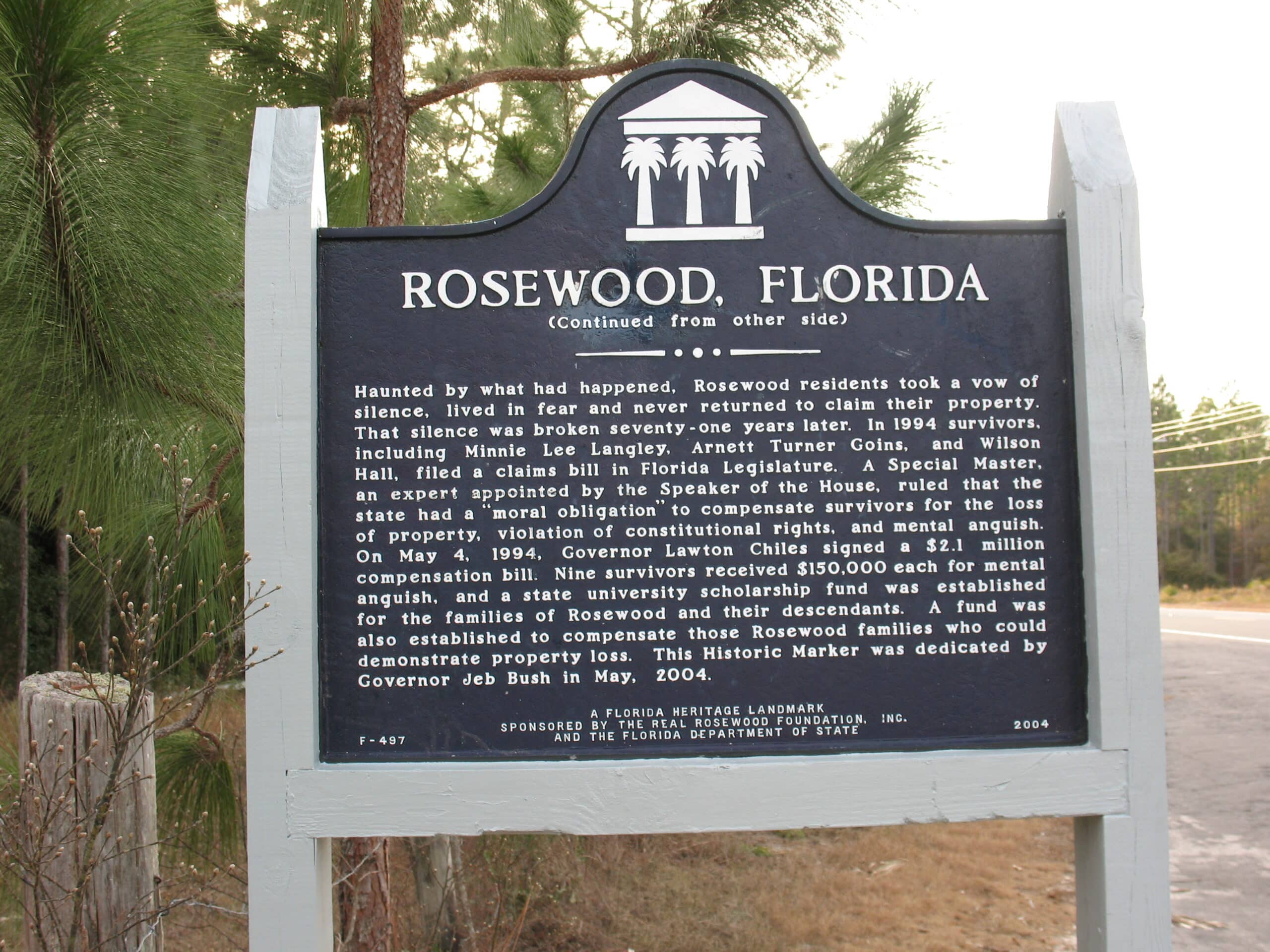

Unlike most Texas communities in the early 20th century, the unincorporated town of Slocum — like Rosewood, Florida — was largely African American, with several Black citizens considerably propertied and a few owning stores and other businesses. This alone, in parts of the South, might have been enough to foment violence. But in the area around Slocum, roughly 100 miles east of Waco, there were other issues, according to newspaper reports and other sometimes conflicting accounts of the massacre.

When a white man reportedly tried to collect a disputed debt from a well-regarded Black citizen, a confrontation occurred. Hard feelings lingered. When a regional road construction foreman put an African American in charge of rounding up help for local road improvements, a prominent white citizen named Jim Spurger was infuriated and became an agitator.

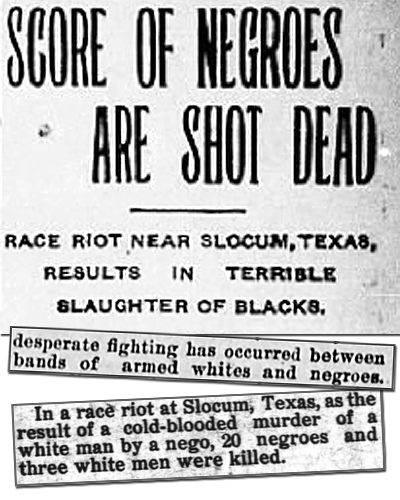

The Slocum violence was reported (in various degrees of truth) in newspapers across the country at the time.

Rumors spread, warning of threats against Anglo citizens and plans for race riots. White malcontents manipulated the local Anglo population and, on July 29, white hysteria transmogrified into bloodshed.

Stoked and goaded by Spurger and others, a collection of white mobs made up of Slocum locals and heavily armed white residents from all over Anderson County roamed through the area in groups of six or seven or in mobs of 30 to 40 and, according to some reports, up to 200. Members of the mobs engaged in what authorities later termed a “potshot” occasion, firing on Black citizens at will. They moved from road to road and cabin to cabin, shooting down African Americans in their tracks. Survivors of the bloodshed spread the word, and African Americans began fleeing. The white mobs followed Blacks into the surrounding forests and marshes and shot many victims in the back as they fled. Several bodies were discovered with bundles of clothing and personal effects at their sides.

Every initial newspaper report on the transpiring bloodshed portrayed the African Americans as armed instigators, but these accounts were heinous mischaracterizations. Anderson County Sheriff William H. Black, of Palestine, Texas, and Special Deputy Godfrey Rees Fowler arrived in the Slocum area, and they discovered a terrified white populace, most of whom had slept overnight in churches and schoolhouses. But it was increasingly apparent that the alleged African American mob that had supposedly conspired to attack the local white community hadn’t materialized.

When reporters gathered on July 31, up to two dozen murders had been reported, but local authorities had only eight bodies. Sheriff Black said it would be “difficult to find out just how many were killed” because they were “scattered all over the woods,” and buzzards would find many of the victims first.

“Men were going about killing Negroes as fast as they could find them,” Sheriff Black told the New York Times. “These Negroes have done no wrong that I can discover,” Black continued. “I don’t know how many were in the mob, but there may have been 200 or 300. They hunted the Negroes down like sheep.”

The truth is, a harrowing number of African Americans were slaughtered in the counties of Anderson and Houston in the mid-summer of 1910. Yet today it’s almost never spoke of, much less widely acknowledged, sufficiently researched, or historically considered, including its omission in A Centennial History of Anderson County, Texas (1936) and History of Houston County, Texas, 1687–1979 (1979).

Context and National Response

In every month for the six months leading up to the Slocum Massacre, an African American in the East Texas region was executed by a white mob based on allegations alone. No trials, no juries — simply white verdicts. After the lynching of Allen Brooks, just four months prior to the Slocum Massacre, a photograph of his hanging body and a crowd of a hundred spectators was made into a postcard that was mailed to friends and family. And these injustices weren’t exceptions to the rule; rather, they were the rule under which African Americans lived and died in that part of the world.

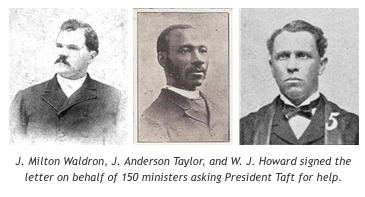

J. Milton Waldron, J. Anderson Taylor, and W. J. Howard signed the letter on behalf of 150 ministers asking President Taft for help.

On August 13, 1910, a group of more than 150 African American ministers from Washington, D.C., sent a letter to President Taft regarding the Slocum Massacre. In the letter, the committee implored President Taft to use the powers of his “great office to suppress lynchings, murder, and other forms of lawlessness” and to do something to “make human life more valuable and law more universally respected.”

The attorney general responded on August 24 with a succinct letter stating, “The protection of life and property is generally a duty devolving up the state authorities,” and continued “Your letter and petition deal with the subject of the treatment of colored persons generally and therefore furnish no facts which would warrant this Department in taking any steps to redress the wrongs complained of.”

Trial and Aftermath

At the initial grand jury hearing of the suspects charged in the Slocum atrocity, nearly every remaining resident was subpoenaed; some refused to testify and were arrested. By the time the grand jury findings were reported on August 17, several hundred witnesses had been examined. Though 11 men were initially arrested, seven were indicted. The grand jury judge moved the trial to Harris County, distrusting the potential jury of peers the defendants might receive in Anderson County. The indictments received no interest or justice in Harris County. Eventually, all those charged were released, and none of the indictments were ever prosecuted.

In the meanwhile, the personal holdings of many Slocum-area Anglo citizens fortuitously increased. The abandoned African American properties were absorbed or repurposed as the now-majority white population saw fit. The standard Southern Anglocentric world order was restored.

The community reflects effects of the event to this day. While most nearby towns have African American populations of 20 percent or more, Slocum’s is just under 7 percent.

Recent Acknowledgments

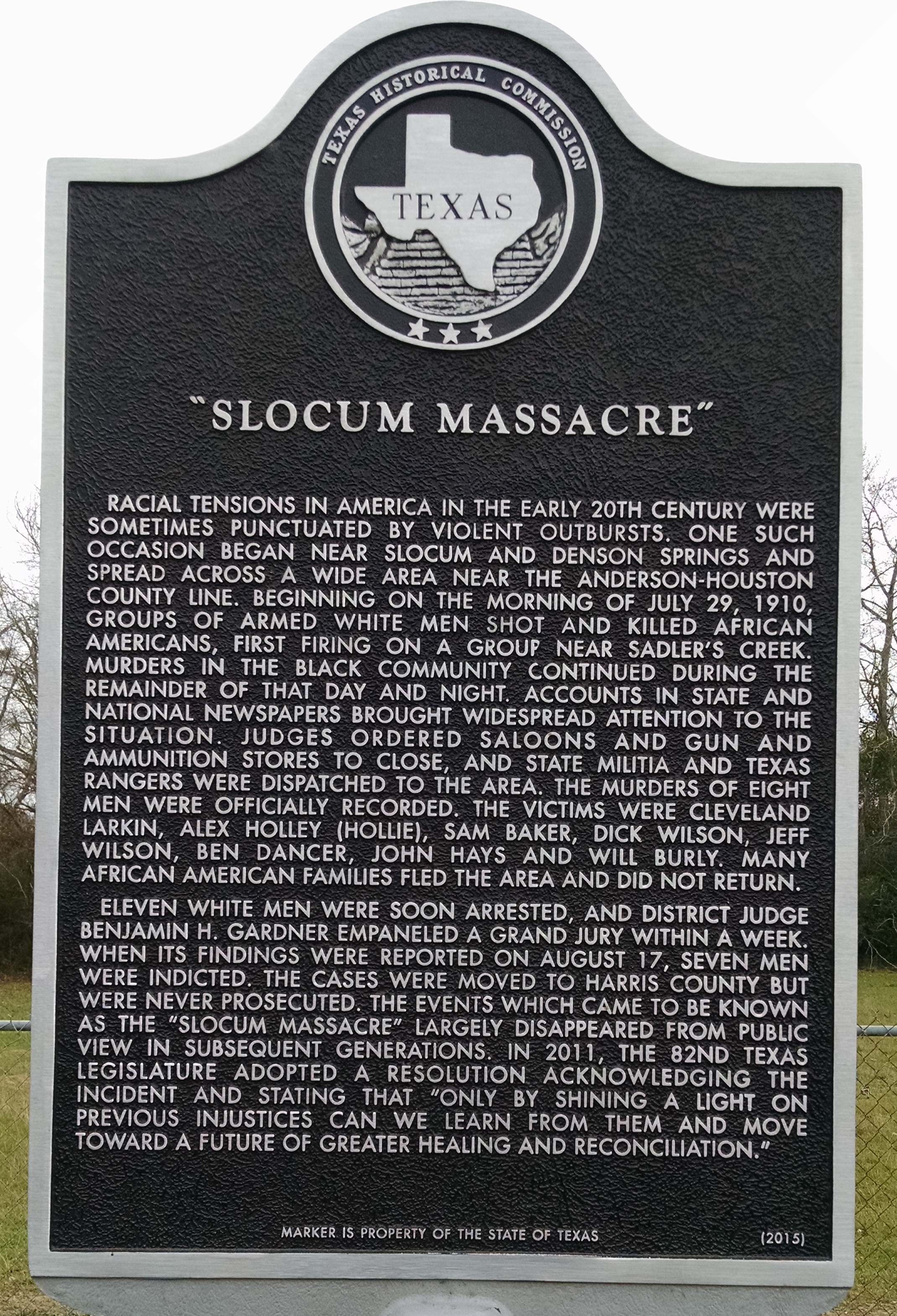

After decades of effort, a marker commemorating the Slocum Massacre was dedicated on Jan. 16, 2016. Click to view larger image.

On March 30, 2011, after a two-part February feature on the Slocum Massacre by Tim Madigan in the Fort Worth Star-Telegram, the 82nd Texas Legislature adopted House of Representatives Resolution 865, acknowledging the incident.

On January 16, 2016, a historical marker to the Slocum Massacre was unveiled. In a Washington Post article, Constance Hollie-Jawaid, who is a descendant of victims of the massacre and who applied for the historical marker, said, “This most definitely helps restore [the Slocum Massacre] to its proper place.” Hollie-Jawaid continued, “It was being ignored, and by ignoring it, you’re spitting in the face of those who died during that tragic event. You’re basically saying either it didn’t happen or it was not important, and it’s very, very important.”

Despite local opposition to the marker, Chris Florance, spokesperson for the Texas Historical Society, told the Washington Post, “There is difficult history in the state, and this shows there has been a lot of change.” Longtime State Judge Bascom Bentley also noted, “I’m glad the marker is there. It’s part of our history, an ugly part. But the purpose of history is to teach us how to do better in the present and future.”

The atrocities committed in the Slocum area in 1910 should give us all pause and spur commitments to definitively establish the truth, fully acknowledge it, and honestly and constructively address it.

E. R. Bills is the author of The 1910 Slocum Massacre: An Act of Genocide in East Texas. Bills received a degree in journalism from Southwest Texas State University in 1990. Reprinted here with permission of the author. Versions of this story have been published on Dissident Voice, the Statesman, and the Patrick Murfin blog.

Our thanks to Constance Hollie-Jawaid (formerly Constance Hollie-Ramirez), a descendant of victims of the 1910 Slocum Massacre, for sharing this story with the Zinn Education Project. Hollie-Jawaid was a Dallas Independent School District principal for many years.

Posted on: Huffington Post.

© 2016 The Zinn Education Project.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn