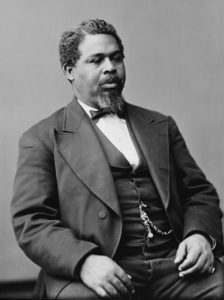

Robert Smalls. Source: Library of Congress

On Sept. 10, 1895, the South Carolina constitutional convention was convened by U.S. Senator Benjamin “Pitchfork” Tillman and his political allies to disenfranchise African Americans and establish Jim Crow segregation.

Robert Smalls, formerly enslaved and a congressman who had helped establish Black civil rights at the 1867 state convention, fought unsuccessfully against the rollback as one of a handful of Black delegates. Here is an excerpt from his speech,

Since reconstruction times 53,000 negroes have been killed in the south, and not more than three white men have been convicted and hung for these crimes. I want you to be mindful of the fact that the good people of the north are watching this convention upon this subject. I hope you will make a Constitution that will stand the test. I hope that we may be able to say when our work is done that we have made as good a Constitution as the one we are doing away with.

. . . How can you expect an ordinary man to “understand and explain” any section of the Constitution, to correspond to the interpretation put upon it by the manager of election, when by a very recent decision of the supreme court, composed of the most learned men in the State, two of them put one construction upon a section, and the other justice put an entirely different construction upon it.

To embody such a provision in the election law would be to mean that every white man would interpret it aright and every negro would interpret it wrong. I appeal to the gentleman from Edgefield to realize that he is not making a law for one set of men. Some morning you may wake up to find that the bone and sinew of your country is gone. The negro is needed in the cotton fields and in the low country rice fields, and if you impose too hard conditions upon the negro in this State there will be nothing else for him to do but to leave.

What then will you do about your phosphate works? No one but a negro can work them; the mines that pay the interest on your State debt. I tell you the negro is the bone and sinew of your country and you cannot do without him. I do not believe you want to get rid of the negro, else why did you impose a high tax on immigration agents who might come here to get him to leave?

Read more of Small’s speech. Read more speeches from the Constitutional Convention at the Library of Congress and the National Archives.

In a roundtable on We Were Eight Years in Power by Ta-Nehisi Coates, Brandon Byrd describes another speaker at the convention:

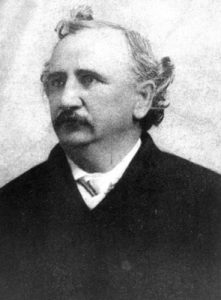

Thomas E. Miller. Source: U.S. House of Representatives.

Thomas E. Miller, a free-born attorney, college graduate, and former U.S. congressman, was one of six black delegates to the convention. He was also one of its most vocal dissidents. Miller knew the convention was supposed to disfranchise black voters and discard the state constitution drafted in 1868. He also understood the propaganda meant to justify the purge.

Tillman, Miller told the convention, condemned Reconstruction-era political corruption but had “not found voice eloquent enough, nor pen exact enough to mention those imperishable gifts bestowed upon South Carolina . . . by Negro legislators.”

“We were eight years in power,” Miller continued. “We had built school houses, established charitable institutions, built and maintained the penitentiary system, provided for the education of the deaf and dumb, rebuilt the jails and court houses . . . In short, we had reconstructed the State.”

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn