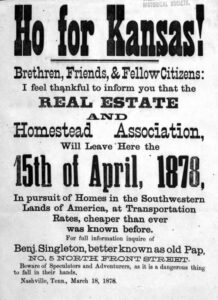

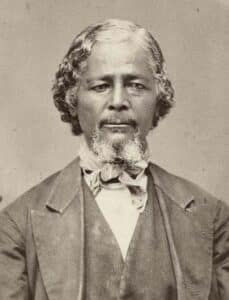

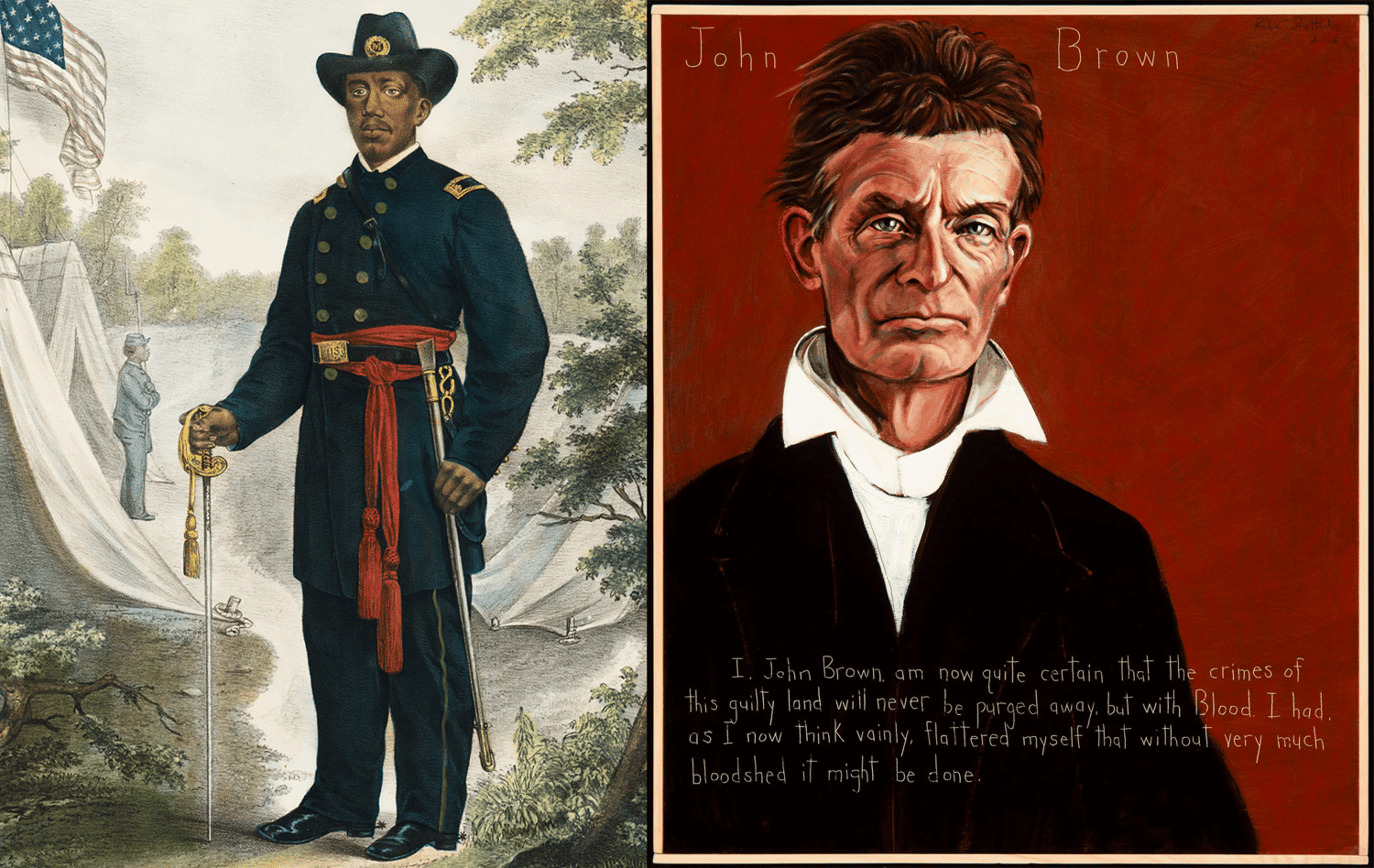

On April 15, 1878, the Edgefield Real Estate and Homestead Association, an organization that helped organize travel and settlement for African Americans, relocated from Tennessee to Kansas. This move was part of a migration pattern growing much more common among Southern Black folks in the 1870s. Benjamin “Pap” Singleton, a formerly enslaved man who escaped to freedom in 1846, was the leader of the movement of formerly enslaved people migrating to Kansas.

Singleton established the Edgefield Real Estate and Homestead Association, but real estate and homestead associations were being created all around the country. While these associations often provided African Americans with opportunities to leave the South, they did advertise with the premise that the land migrants were moving to was unoccupied and free for migrants to claim, both of which were untrue. For tens of thousands of years, present-day Kansas and the area around the state had been stewarded by various Indigenous nations. In Kansas, specifically, various removal policies forced the Kaw Nation, Osage Nation, Kiowa Nation, Comanche Nation, Pawnee Nation, the Oceti Sakowin Oyate Nation, and others to leave their land.

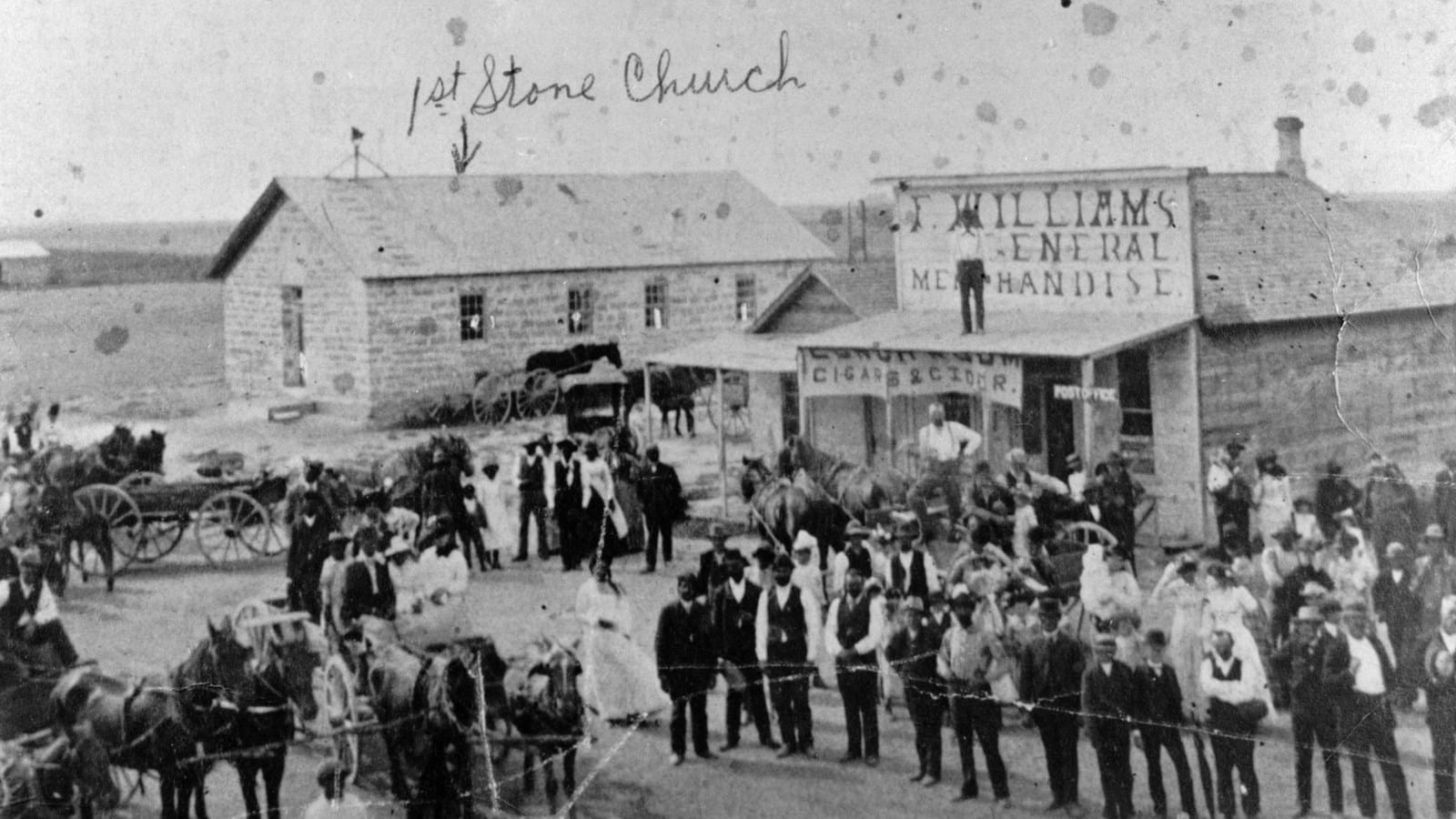

Known by many as a “Black Moses,” Singleton promoted “Sunny Kansas” as “one of the finest countries for a poor man in the world.” Between 1877 and 1878, almost 300 African Americans migrated to Kansas, largely due to Singleton and his advertising. The first migrants to Kansas primarily settled in Singleton’s Colony and Wyandotte, but in 1879 and 1880, a second wave of around 20,000 African Americans migrated to Kansas, part of a larger national movement of people called the “Exodusters.”

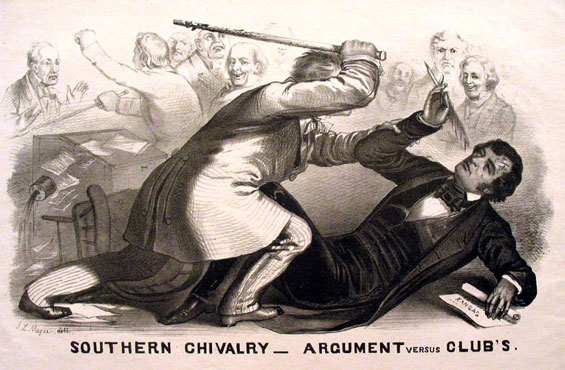

The Exodusters fled the South because of racial violence by white supremacist groups. Singleton promised Black Southerners that Kansas would be the land of promise, a place where they could escape all of the racial violence they were experiencing in the South.

A broadside distributed by Benjamin Singleton advertising migration to Kansas, 1878. Source: Kansas Historical Society

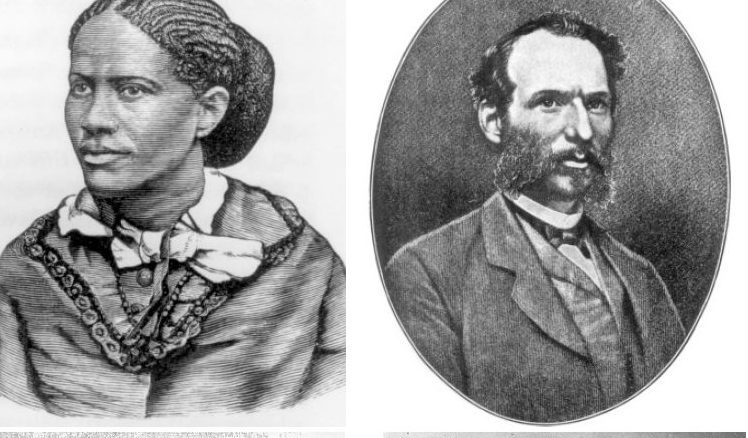

Many of these migrants found themselves stranded in St. Louis, as some steamboat captains refused to take them across the Missouri River. Because of this, Black churches in St. Louis and philanthropists formed the Colored Relief Board to help provide aid to migrants, a responsibility that fell almost entirely upon Black St. Louisans. Even William Lloyd Garrison, a prominent white abolitionist, suffragist, and founder of the newspaper The Liberator, got involved, raising money by writing letters to community leaders across the country.

Songs and posters were created and circulated, such as the song “The Land That Gives Birth to Freedom.” Posters demonstrated how this exodus was seen as the “new style,” whereas escaping enslavement was seen as the “old style.” Because of the sheer amount of Black people migrating to Kansas, resources were extremely limited and conditions were rough.

In 1879, Kansas Gov. John St. John established the Kansas Freedmen’s Relief Association to help support the Exodusters once they arrived in Kansas. Based in Topeka, the association helped Black migrants across the state.

For more primary sources on the Exodusters, see the Digital Public Library of America collection.

This story was prepared by May Kotsen, an intern with the Zinn Education Project in summer 2022.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn