A deadly munitions explosion occurred on July 17, 1944, at the Port Chicago Naval Magazine in Port Chicago, California. As a result of the disaster, 320 men died (two-thirds of whom were African American), 200 African American men protested, and 50 of them faced court-martial and jail for challenging working conditions. This is a key story in World War II and Jim Crow history.

Here is a description from “Commemorating the Port Chicago Naval Magazine Disaster of 1944: Remembering the Racial Injustices of the ‘Good War’ in Contemporary America.”

Following the disaster, many of the white officers at the Port Chicago base asked for and were granted 30 days leave. African American sailors were refused leave and were assigned the gruesome task of clearing the area of wreckage and searching for remains. Of the 320 dead, only 51 bodies were sufficiently intact to be positively identified. Then, just a few weeks after the disaster, and with no discussion of why the horrific explosion of July 17 had occurred or how to prevent such a disaster from happening again, the black sailors were ordered back to work loading ordnance at the Mare Island Navy Yard in Vallejo.

Over 250 of the men refused, understandably terrified by the possibility of another explosion—especially since their dangerous circumstances remained unchanged: there continued to be no training in munitions handling, and officers continued to encourage the rushed, and competitive, loading of ordnance. As Joe Small, a survivor of the Port Chicago explosion, later recalled: “I wasn’t trying to shirk work. I don’t think these other men were trying to shirk work. But to go back to work under the same conditions, with no improvements, no changes, the same group of officers that we had, was just—we thought there was a better alternative” (qtd. in Thompson; see Allen 76–77). Under threat of the death sentence for “mutinous conduct” during wartime, 208 of the African American sailors agreed to return to work. But fifty of them, including Joe Small, refused and were charged with mutiny. Court-martialed together, the “Port Chicago 50” were found guilty and sentenced from eight to fifteen years of hard labor in federal prison at the Terminal Island Disciplinary Barracks in San Pedro. All of the men were dishonorably discharged. [Continue reading here.]

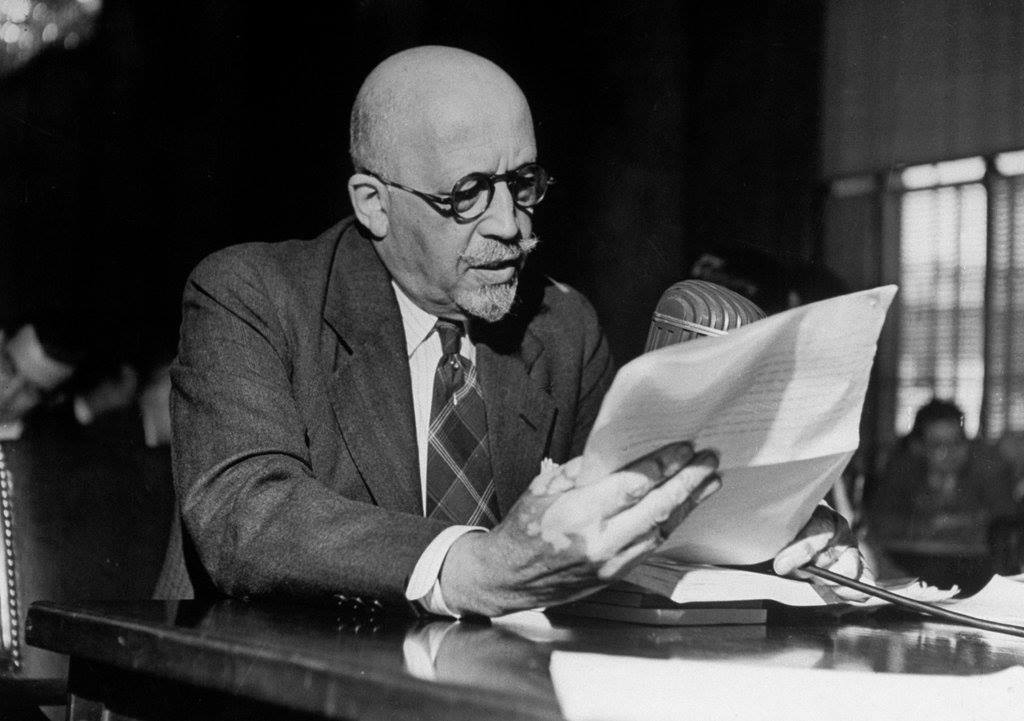

Thurgood Marshall was present at the trial and he voiced the frustration and anger of the men on trial who were told to return to work with no change in the conditions that led to the explosion. Marshall said:

This is not fifty men on trial for mutiny. This is the Navy on trial for its whole vicious policy towards Negroes.

At a 76th anniversary event in Vallejo, California, attendees read a list of the Port Chicago 50. Their names are:

Julius J. Allen, Mack Anderson, Douglas G. Anthony, William E. Banks, Arnett Baugh, Morris Berry, Martin A. Bordenave, Ernest D. Brown, Robert L. Burnage, Mentor G. Burns, Zack Credle, Jack P. Crittenden, Hayden R. Curd, Charles L. David, Jr, Bennon Dees, George W. Diamond, Kenneth C. Dixon, Julius Dixon, John H. Dunn, Melvin W. Ellis, William Fleece, James Floyd, Ernest J. Gaines, John L. Gipson, Charles C. Gray, Ollie L. Green, Harry E. Grimes, Herbert Davis, Charles N. Hazzard, Frank L. Henry, Richard W. Hill, Theodore King, Perry L. Knox, William H. Lock, Edward L. Longmire, Miller Matthews, Augustus P. Mayor, Howard McGee, Lloyd McKinney, Alpohnso McPherson, Freddie Meeks, Cecil Miller, Fleetwood H. Postell, Edward Saunders, Cyril O. Sheppard, Joseph R. Small, William C. Suber, Edward L. Waldrop, Charles S. Widemon, and Albert Williams, Jr.

Further Reading

Read “War, ‘mutiny’ and civil rights: Remembering Port Chicago” to learn more.

Read “War, ‘mutiny’ and civil rights: Remembering Port Chicago” to learn more.

Two key books on this event are The Port Chicago Mutiny: The Story of the Largest Mass Mutiny Trial in U.S. Naval History and, for young adults, The Port Chicago 50: Disaster, Mutiny and the Fight for Civil Rights.

We also recommend Being Clem, the third book in a must-read middle-school Finding Langston trilogy of historical-fiction Lesa Cline-Ransome, set in World War II era Chicago. Protagonist Clem is 9-years-old when his father is killed in the Port Chicago Disaster.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn