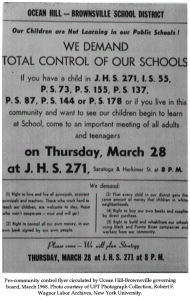

Ocean Hill – Brownsville parents organized through notices like this in spring 1968. Source: UFT Photo Collection, Robert F. Wagner Labor Archives, NYU.

In Brooklyn, in the early spring of 1968, Black and Puerto Rican parents organized for better schools for their children. Their demands were as follows:

- The right to hire and fire all principals, assistant principals, and teachers. Those who work hard to teach our children are welcome to stay. Those who won’t cooperate — must and will go!

- Right to control all our own money, in our own bank.

- That every child in our district gets the same amount of money [as] children in white neighborhoods.

- Right to buy our own books and supplies by direct purchase.

- Right to build and rehabilitate our schools using Black and Puerto Rican companies and workers from our own communities.

In response to their demands, the central board of education approved a pilot community school program. The new, community-level school boards replaced the top-down civil servants and school board decision-makers. In this pilot program, school districts were given the power to make hiring, policy, and budget decisions at a local level.

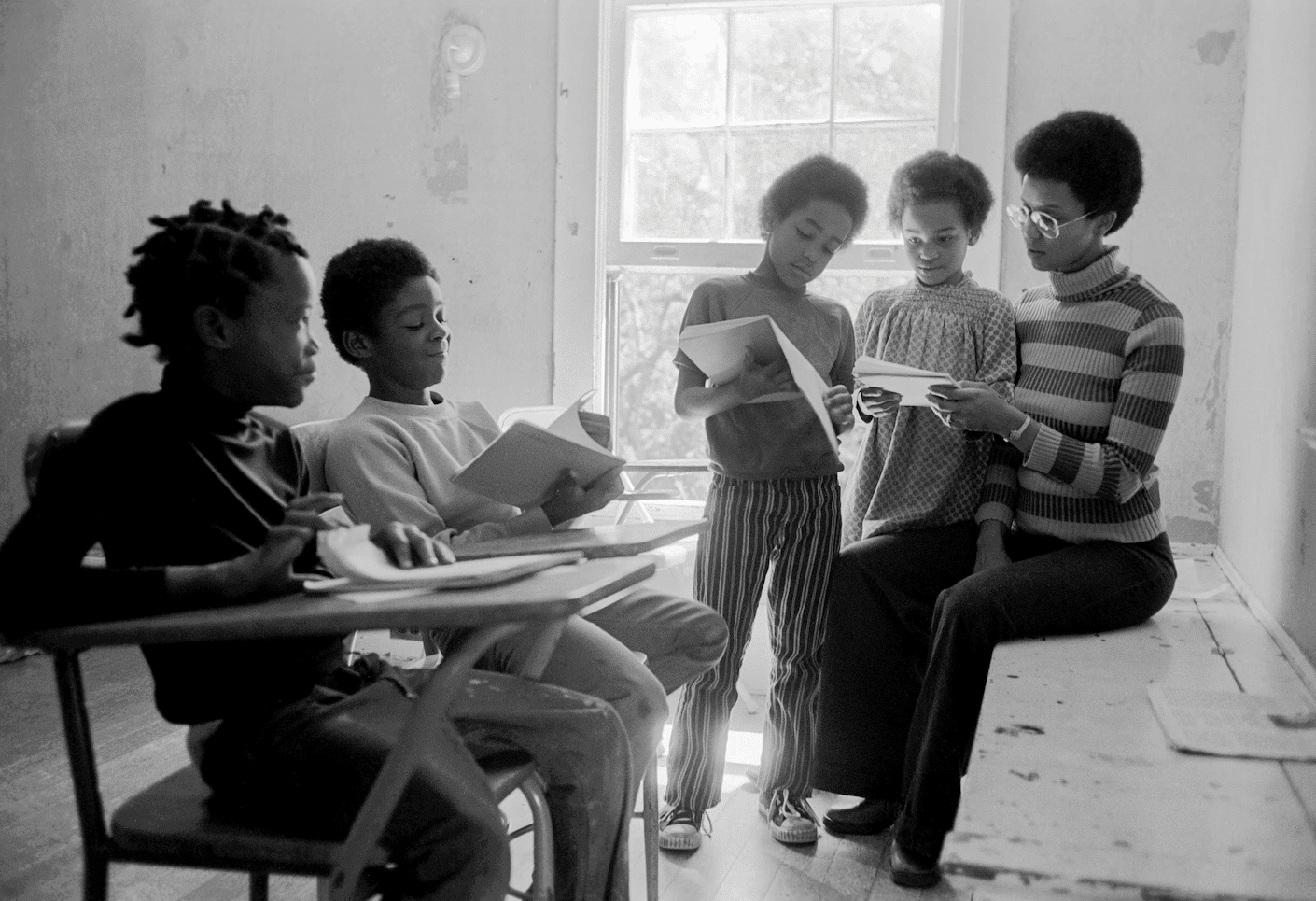

Brooklyn parents demonstrated for their children’s right to a quality education. Source: School Colors Podcast

On May 9, 1968, the majority-Black and Puerto Rican community school board in Ocean Hill-Brownsville fired 19 white, union teachers who they determined were under-performing. The union, which was accustomed to negotiating with the centralized board of education and the city, was not prepared to negotiate with new, neighborhood-level governing boards. A Chalkbeat article described it as the breaking point:

I think it’s fair to say this is the spark, said Nick Juravich, a postdoctoral fellow at the New-York Historical Society who has studied the teachers’ dismissal. This is when what has been a simmering conflict becomes an actual confrontation.

New York’s United Federation of Teachers refused to acknowledge the community school board’s right to terminate and went on the offensive. The push-back started with walkouts and then there was a series of three strikes, including city-wide strikes. In the end, the city representatives and the teachers union struck a deal without input from the community boards and the teachers were reinstated. The communities lost local control of their children’s schools and the entire school system was reorganized.

Vincent Harding said in Hope and History,

It may be, then, that if our students understand these things, they will also see and hear more clearly the meaning of educational and political struggles like the one that the second part of the Eyes on the Prize series documents from the Ocean Hill-Brownsville section of Brooklyn. For in this and similar settings across the nation, Black parents sought to take greater democratic responsibility for the education of their children.

They did it partly in order to break the hegemony of insensitive, often destructive, white-defined and -controlled education in their schools. They did it as well in order to test the possibilities of democracy and the great, untapped potentials of their children.

In a sense, they were parenting both their natural offspring and the possibilities of their nation. Because we are still young in our life as an officially democratic, multiracial society, this struggle for a democratic content and organization for the educational process must continue for a long time.

Listen

The School Colors podcast produced a multi-episode series on education during the Civil Rights era. In its third episode, hosts Mark Winston Griffith and Max Freedman feature the voices of Charlie Isaacs, Sandra Feldman, and Cleaster Cotton:

MAX: There were more than a million students in New York City public schools, and the teachers’ strike was hugely disruptive for them and their families.

MARK: But in Ocean Hill-Brownsville, schools were open for business. Eight schools — six elementary schools, two middle schools — stayed open throughout the strike, staffed by 300 replacement teachers hired over the summer. But most of the city’s attention focused on one school: Junior High School 271. Every day, the street in front of 271 was a circus: union teachers picketing, activists protesting the picketers, police keeping the picketers and the protesters apart, and reporters weaving in and out.

MARK: Charlie Isaacs was a twenty-three year old math teacher at 271. He was no stranger to strikes — in fact, he had organized a student strike in college.

CHARLIE ISAACS: Well this wasn’t a strike against management, this was a strike against the community, against the kids. And they were nasty. They called people all kinds of names, they called me out by name, I don’t even know how they knew who I was. They pretty quickly made it very easy to go past those picket lines.

MAX: Sandra Feldman remembers the nasty name-calling going in the other direction — from people like Charlie, people on the side of community control, at the union. She was sent by the union to personally escort striking teachers to picket in front of 271 every day.

SANDRA FELDMAN: Teachers were frightened. They were on the picket lines and they would get yelled at and called names and it was a very, very painful, it was agonizing for the teachers. A lot of the teachers especially who had taught in, in that school district for many years and who were committed to the kids.

MARK: If it was agonizing for the teachers, it was traumatizing for the kids.

CLEASTER COTTON: For me the scene was a war zone.

MARK: Cleaster Cotton was the student body president at 271, and lived across the street.

CLEASTER COTTON: There were so many people. There were thousands of police. There were snipers with guns on the roofs. Sometimes there were helicopters. There were police on horses. There were police with canine units with mean dogs. The reporters with the fedora hats and the little pads with the pencils. The photographers with the light bulbs when they flash it.

Learn More

- The Tough Lessons of the 1968 Teacher Strikes in The Nation

- The 1968 New York City School Strike Revisited in Commentary Magazine

- Ocean Hill-Brownsville, Fifty Years Later and The UFT’s Opposition to the Community Control Movement in Jacobin Magazine

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn