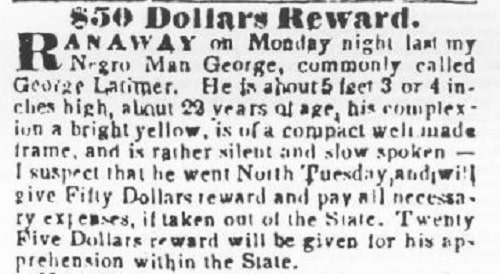

New York state abolished slavery within its borders in 1827, but Black New Yorkers remained in danger of enslavement or re-enslavement through widespread kidnapping conspiracies and crimes of opportunity. Black sailors would go missing from ports. Children would disappear on their way home from school or from poor houses. Black servants who traveled into slave states with their employers found themselves isolated and sold against their will, and then “disappeared” into the deep South. People held in New York City’s municipal prison cells would find themselves sold to slave traders by unscrupulous police officers. New York City’s police were infamous for operating in the city’s “kidnapping clubs.”

New York state abolished slavery within its borders in 1827, but Black New Yorkers remained in danger of enslavement or re-enslavement through widespread kidnapping conspiracies and crimes of opportunity. Black sailors would go missing from ports. Children would disappear on their way home from school or from poor houses. Black servants who traveled into slave states with their employers found themselves isolated and sold against their will, and then “disappeared” into the deep South. People held in New York City’s municipal prison cells would find themselves sold to slave traders by unscrupulous police officers. New York City’s police were infamous for operating in the city’s “kidnapping clubs.”

David Ruggles served as a founder and secretary for the New York Committee of Vigilance, a radical antislavery and Black self-defense organization.

On November 20, 1835, to fight back against the onslaught of oppression, Black abolitionist and businessman David Ruggles helped to found the New York Committee of Vigilance (NYCV), a multi-racial organization that would defend Black New Yorkers from predatory whites, especially police officers. Jamila Shabazz Brathwaite, a scholar of Black resistance in the North and author of the paper “The Black Vigilance Movement in Nineteenth Century New York City,” writes,

Ruggles fearlessly boarded ships in the New York harbor in search of Black captives or for signs of participants in the illegal slave trade. He published a list of Northern actors who he believed participated in the kidnapping of free Blacks. He assisted fugitives to safety and guided them on to points North or to freedom in Canada. He along with others in the vigilance network petitioned for jury trials in the cases of those arrested as fugitives.

This work would not have been possible without the efforts of the Black community on the ground level. The unnamed men and women passed along intelligence, fed, clothed, and helped to shelter fugitives. They also reached into their shallow pockets to financially support the movement. The NYCV depended upon informants who as they went about their daily lives took note of suspicious activities and people.

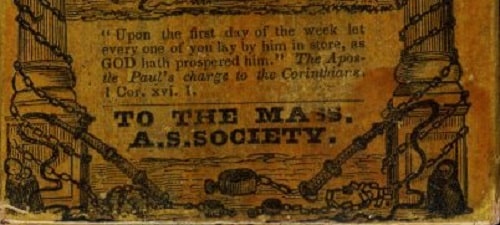

. . . The New York Committee of Vigilance published the organization’s first annual report for the year of 1837 and announced that they had raised nearly $840 dollars to support their work. Although their fundraising had been successful, the organization completed the year in debt. Funds were used to cover fees for lawyers, to provide food, clothing, shelter, and transportation for fugitives. The NYCV also spent funds to recover Blacks detained in the South and pursued the recovery of property owed to Blacks due to bequeaths from whites.

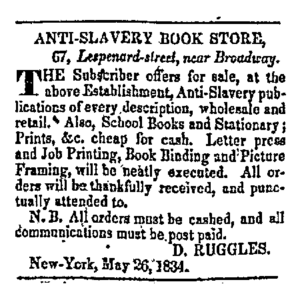

An advertisement for Ruggles’ bookstore on Lespenard Street. It is the first known Black-owned bookstore in the United States.

Ruggles was also an organizer for the Underground Railroad and writer, who published his own pamphlets and contributed to abolitionist papers like The Liberator. He was responsible for activating a series of safehouses for freedom seekers in the New York region. Notably, Frederick Douglass and Anna Murray were married in Ruggles’ New York home after they fled Maryland.

The NYCV struggled against white supremacy and slavery for over a decade, often at deep personal cost to its members. Slave catchers, police officers, politicians, merchants, and moderate abolitionists were all enemies of the NYCV activists. They lived in fear of being discovered, sued, arrested, and assaulted. Ruggles, who served as the committee’s Secretary from its founding, was forced to retire from activism and move away from the city when his health suffered. Steven H. Jaffe describes the victories of the organization in Lapham’s Quarterly and explains how it “inspired the creation of similar groups in Philadelphia, Albany, Boston, Rochester, Cleveland, Detroit, and elsewhere, all bent on helping African Americans to flee from and resist slavery.”

Learn More

The Kidnapping Club: Wall Street, Slavery, and Resistance on the Eve of the Civil War by Jonathan Daniel Wells (2020)

“They Keep People Safe,” an episode of the podcast Empire City

“The Black Vigilance Movement in Nineteenth Century New York City” by Jamila Shabazz Brathwaite (2014)

“David Ruggles’ Committee of Vigilance: Fighting against slavery in New York, a city loath to acknowledge its horrors” by Steven H. Jaffe (2018)

The David Ruggles Home interpreted by Mapping the African American Past

“The Black New Yorker Who Led the Charge Against Police Violence in the 1830s” by Jonathan Daniel Wells (2020)

Visit the David Ruggles Center for History & Education for information about nineteenth-century abolitionists and the Underground Railroad

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn