By Adam Wasserman

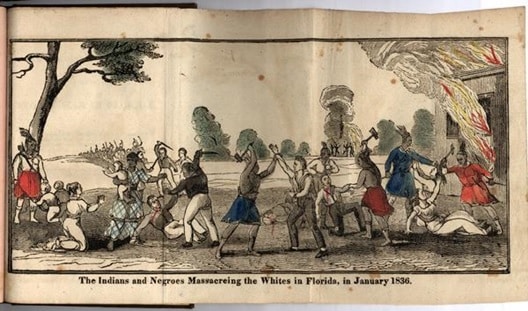

The War of 1812, in modern textbooks, is known for the Star-Spangled Banner, the burning of the White House, and the Battle of New Orleans. While the Southeastern theater of war, likely because it carried more significant and uncomfortable ramifications for America’s foundations — native land theft, genocide, and slavery — is hardly a footnote in those very books. The Southeast featured irregular and low-scale insurgency of British, Blacks and Indigenous against the plantation frontier. Settler expansionists meanwhile used the war to wrench land, expand slavery, and claim new American territory. The war crafted what would later become the Monroe Doctrine, an exclusive American right to intervene in borderlands where hostile Europeans could invoke savage and servile warfare. This “right” would lead to claims of natural right to territory that was vital to American defense and prosperity, justifying their theft and annexation by coercion in Florida, Texas, California, and elsewhere. Manifest Destiny was enshrined in the southeast theater and practiced most deftly by Andrew Jackson and his base of settler intriguers.¹

Warriors from Bondage. The attack of Negro Fort on the Apalachicola River, 1816. Source: Jackson Walker Studio

On the other side, a Pan-Indian movement exploded on the eve of war. In 1811, Shawnee leader Tecumseh carried the message of unity to the southeast in the interest of establishing a common front against the American advance on their lands. His admonitions of Indigenous unity against white Americans found a receptive audience in a significant core of the Upper Creeks in central Alabama. This influential and powerful group of anti-American Creek warriors, known as Red Sticks, grew determined to resist the onset of land-grabbing white settlers and particularly targeted Creek collaborators. The Creek rift accelerated between militant Red Stick Creeks and pro-white Lower Creeks, particularly Cowetas, who had accepted white institutions like private property and chattel slavery.

Depiction of Andrew Jackson and Chief William Weatherford, Treaty of Fort Jackson

By 1813, civil war erupted and the U.S. military under General Andrew Jackson quickly came to the support of their Creek allies. The war was brutal, characterized by multiple massacres. The famed Davy Crockett, a volunteer in the war, recounted “we shot them like dogs.”² Africans sided with Red Sticks from the start of the war, aiding in the assault and destruction of Fort Mims. Some of these self-emancipated slaves took up arms with the Red Sticks and fought valiantly at the Battle of Econochoca, or Holy Ground, where twelve were killed in the conflict. At Econochoca, one U.S. officer reported, “the negroes were the last to quit the ground.”³ On March 27, 1814, the Red Stick resistance was defeated at the battle of Horseshoe Bend. In August that year, Jackson’s friendly Creek leaders ceded over 23 million acres in the treaty of Fort Jackson, intolerable terms for the majority of Creeks. The treaty would birth the Cotton Kingdom and the Second Middle Passage — the domestic slave trade on the Mississippi River — that would supply forced labor to the rising cotton empire.

In defiance of the treaty, eight towns of Red Stick Creeks, numbering up to 2,000 inhabitants, including 800 warriors, crossed the Florida border and settled on the outskirts of Pensacola. Among the wave of refugees was a half-white 8-year old boy named Powell, later known as Asi-Yahola (Black Drink), or Osceola. The British now looked to Pensacola as their new base of operations in the Southeast. In August, British officers Colonel Edward Nichols and Captain George Woodbine occupied Pensacola, with Spanish support, in order to build a Black and Indigenous army to harass the plantations and seize New Orleans. They provided relief and arms to their Red Stick allies while recruiting one hundred Black Pensacolans, enslaved and free alike, to the ranks of the Royal Colonial Marines.4 Under Admiral Alexander Cochrane’s emancipation proclamation, issued in April, all Black recruits were promised freedom and land in the West Indies.5 Nichols, a fervent abolitionist, emancipated slaves regardless of master — Spanish, British, and American alike. At least 25 of the freed slaves belonged to John Forbes and Company, the British Indian trading monopoly, including the future famed Black Seminole leader Abraham.6

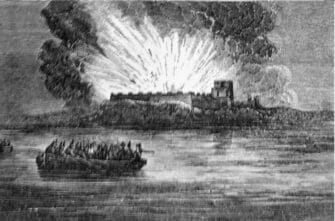

Blowing up of Fort Barrancas in 1814, in Pensacola

The insurrectionary threat on the Louisiana-Georgia border was too much for slaveholders to tolerate. Andrew Jackson claimed the British goal was to “excite the Black population to insurrection & massacre.”7 On November 7, his forces crossed the Florida border and surrounded the city. The British, joined by thousands of Red Sticks and three hundred emancipated Pensacolan slaves, retreated to ships anchored off the coast and detonated Fort Barrancas as they left.8 The fleet sailed about one hundred miles east to a cliff overlooking Prospect Bluff, fifteen miles up the mouth of the Appalachicola River. Here they began construction of a fort that was to become the epicenter of British, Black and Indigenous opposition.

Forced to other fronts of the war, Jackson didn’t pursue but instead commissioned his close ally, Coweta Creek chief William McIntosh, to retrieve the Pensacolan fugitives. On November 23, McIntosh marched to Appalachicola with 196 warriors, twenty rounds of ammunition, and twenty days’ provisions. It was expected that he was to be reinforced along the way by several hundred more warriors, enough to accomplish the object of the mission. Jackson wrote to Creek agent Benjamin Hawkins: “I hope to hear in a few days Major McIntosh having captured all the stores and negroes on the Apalachicola.”9 Apparently the slave raid was unsuccessful. By December, up to 3,500 warriors were training for war at Prospect Bluff — a coalition of refugee Red Stick Creeks, Miccosukees, Seminoles, and Black maroons.10 General Gaines estimated 900 native warriors and 450 armed Blacks inhabited the fort, but likely didn’t account for the influx of insurgents.11

British fleet off Pensacola

With the British defeat at the battle of New Orleans, Nichols left Appalachicola early in the summer and traveled with a delegate of Red Stick Creeks to Britain, hoping to renew the Crown’s support for the ongoing Florida insurgency. Nichols left behind a large supply of arms, artillery, and ammunition including 2,500 stands of musketry, 500 carbines, 500 steel scabbard swords, four cases containing 200 pistols, 300 quarter casks of rifle powder, 162 barrels of cannon powder, and a large count of military stores. On the walls of the fort were mounted four long twenty-four pounder cannon, four long six-pounder cannon, a four-pound field pierce, and a five-and-a-half-inch howitzer.12 Nonetheless, the vast majority of natives soon abandoned Prospect Bluff and returned to their towns, leaving 300 Blacks in control of the fort.13 An additional 300 to 400 runaways were estimated to have augmented their numbers by this time. A letter from General Gaines on May 14 declared: “Certain Negroes and outlaws have taken possession of a Fort on the Appalachicola River in the territory of Florida.”14 Before Nichols had even left, the Black maroons already begun taking possession of the fort. The Seminoles “were kept in awe” at the hundreds of armed Blacks in the vicinity. “For a period,” William H. Simmons claimed, the Seminoles “were placed in the worst of all political conditions, being under a dulocracy or government of slaves.15 James Innerarity, junior partner of John Forbes & Company, depicted the situation:

Our Store is broken up with considerable loss, over & above that of our Cattle eaten by the plunderers, & negroes robbed by them-our influence over those Indians dead, or expiring, & Prospect Bluff & the Lands in possession of the Negroes . . . They would not deliver up the Negroes; no, that could not be done without a violation of British faith!!! Which had been pledged for their freedom, but they left them at Prospect Bluff (after having trained them to Military discipline) in possession of a well constructed fort, with plenty of provisions, & with Cannon Arms & Ammunition of every description, not only in abundance but in Profusion for their defence-report says, they have even since sent them an accession of Strength, and they are now organized as Pirates, have several small Vessels well armed, & some Piracies that lately occurred in the Lakes are supposed to have been committed by them.16

The fort grew from a strategically defensive base to a flourishing Black maroon community lining the fertile banks of the Appalachicola. They cultivated fields extending fifty miles up the river, using generations of inherited knowledge of West African agricultural techniques. Runaway slaves were pouring in on a daily basis and the community soon grew to about 1,000 Blacks in the fields surrounding the fort.17 Colonel Robert Patterson wrote about the Appalachicola Fort:

The fort grew from a strategically defensive base to a flourishing Black maroon community lining the fertile banks of the Appalachicola. They cultivated fields extending fifty miles up the river, using generations of inherited knowledge of West African agricultural techniques. Runaway slaves were pouring in on a daily basis and the community soon grew to about 1,000 Blacks in the fields surrounding the fort.17 Colonel Robert Patterson wrote about the Appalachicola Fort:

The force of the negroes was daily increasing; and they felt themselves so strong and secure that they had commenced several plantations on the fertile banks of the Appalachicola, which would have yielded them every article of sustenance, and which would, consequently, in a short time have rendered their establishment quite formidable and highly injurious to the neighboring States.18

The fort was becoming a growing threat to slavery itself. Reports about the inhabitants “committing depredations” concealed the true crime they were guilty for war to “inveigle negroes from the citizens of Georgia, as well as from the Creek and Cherokee nations of Indians.”19 Patterson advised its speedy elimination:

The service rendered by the destruction of the fort, and the band of negroes who held it, and the country in its vicinity, is of great and manifest importance to the United States, and particularly those States bordering on the Creek nation, as it had become the general rendezvous for runaway slaves and disaffected Indians; and asylum where they were assured of being received; a stronghold where they found arms and ammunition to protect themselves against their owners and the Government.20

Military officials and slaveholders planned its destruction. On May 21, a British “gentleman of respectability” from Bermuda wrote a memorandum disapproving Col Nichols for having “espoused the cause of the slaves.” He wrote of the “Negro Fort”: “No time ought to be lost in recommending the adoption of speedy, energetic measures for the destruction of a thing held so likely to become dangerous to the state of Georgia.”21

On March 15, 1816, Secretary of War William C. Crawford ordered Andrew Jackson to call the West Florida governor’s attention to the fort. If the Spanish governor refused or was unable to “put an end to an evil of so serious nature,” then Jackson was to promptly take the “necessary measures” to reduce it. On April 23, Jackson transmitted Crawford’s demands to Governor Jose Masot to “destroy or remove from out frontier this banditti, put an end to an evil of so serious a nature, and return to our citizens and friendly Indians inhabiting our territory those negroes now in said fort, and which have been stolen and enticed from them.”22 The Savannah Journal concurred with this sentiment:

It was not to be expected, that an establishment so pernicious to the Southern States, holding out to a part of their population temptations to insubordination, would have been suffered to exist after the close of the war. In the course of last winter, several slaves from this neighborhood fled to that fort; others have lately gone from Tennessee and the Mississippi Territory. How long shall this evil, requiring immediate remedy, be permitted to exist?23

However, such a major threat to the slave system would not be dealt with in the realm of laws or diplomacy. Jackson’s request to the Spanish governor only gave a façade of legitimacy to the inevitable designs of the U.S. government. On April 8, two weeks before Jackson wrote the Spanish governor, he ordered General Gaines to destroy the “Negro Fort” regardless of its location on Spanish territory:

I have little doubt of the fact, that this fort has been established by some villains for rapine and plunder, and that it ought to be blown up, regardless of the land on which it stands; and if your mind shall have formed the same conclusion, destroy it and return the stolen Negroes and property to their rightful owners.24

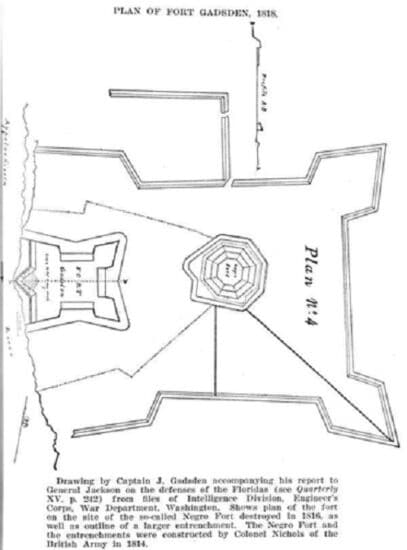

Gaines himself believed that the fort would “produce much evil among the Blacks of Georgia, and the eastern part of the Mississippi territory.”25 He ordered Lt. Colonel Duncan Lamont Clinch to speedily establish a fort near the junction of the Flint and Chattahoochee rivers, where they joined to form the Appalachicola, to intimidate the “Negro Fort.” Clinch was to meet the convoy of supplies from New Orleans with fifty soldiers once he was informed that they had arrived at the river. The convoy was detached with two gunboats. From that point, Gaines ordered him to proceed to the fort where if he was to “meet with opposition” then “arrangements will immediately be made for its destruction.” Gaines wished to provoke an attack to justify the destruction of the fort. For this purpose, Clinch was supplied with two eighteen-pound cannons and one howitzer.26

Portrait of Duncan Lamont Clinch

On July 10, the supply convoy reached the mouth of the Appalachicola and received a dispatch from Col. Clinch ordering them to hold their position until he could arrive with troops to escort them up the river. On July 17, a party of five men, sent to gather fresh water, discovered a Black man on the banks of the river. Successfully luring them on shore, the party was then ambushed by about forty Blacks and Seminoles hidden in the bushes. Three of the men were immediately killed, one dove into the water and made it back to the convoy, and the other was captured.27

On that same day, Clinch commenced to Prospect Bluff with 116 soldiers and met a party of slave-hunting Coweta Creeks under William McIntosh. In addition to Clinch’s excursion, Jackson had commissioned McIntosh with his band of 150 Coweta Creeks to capture the Blacks at the Appalachicola River – rewarded with fifty dollars for every fugitive slave they seized and returned to the owner. After holding a council, McIntosh’s Creeks agreed to keep parties in advance and capture every Black they encountered. On the 19th, they caught a Black Seminole in possession of a scalp — belonging to one of the Americans in the ambushed party — en route to get assistance from the Seminoles.

On the 20th, Clinch’s troops left with the Creek mercenaries and came within gunshot range of the fort, but found it was impossible to destroy without artillery. They were forced to wait until the gunboats from the supply vessel arrived to begin a full assault. McIntosh was ordered to surround the fort with a third of his force and maintain an irregular fire as a diversion. The Blacks fired artillery back but to no avail. On the 23rd, the Creeks demanded that the Blacks surrender but the fort’s commander Garcon, “a French negro,” responded “he would sink any American vessels that should attempt to pass it; and he would blow up the fort if he could not defend it.”28 He then hoisted the English Union Jack accompanied with a red flag over the fort. For the next several days the Blacks opened fire whenever any troops appeared in their view. On July 27, the gunboats approached the fort. The Blacks opened fire when they entered into gunshot range. The gunboats fired back with some cold shots to test the distance. The gunboats then fired “the first hot one,” made red-hot in the cook’s galley, which went screaming over the wall and into the fort’s magazine full of gunpowder. The “lucky shot” totally detonated the fort. Clinch reported the horrific destruction:

The explosion was awful, and the scene horrible beyond description. Our first care, on arriving at the scene of the destruction, was to rescue and relieve the unfortunate beings who survived the explosion. The war yells of the Indians, the cries and lamentations of the wounded, compelled the soldier to pause in the midst of victory, to drop a tear for the sufferings of his fellow beings, and to acknowledge that the great Ruler of the Universe must have used us as his instruments in chastising the blood-thirsty and murderous wretches that defended the fort.29

Out of the 330 men, women, and children inside, 270 were killed instantly and half of the remaining sixty were mortally wounded. Only thirty survived including Garcon and a Choctaw chief. From one of the captives, they had learned that the Blacks had tarred and feathered a captured American soldier.30 The Creeks executed Garcon and most of the survivors with the exception of several Blacks who were re-enslaved, including a St. Augustine runaway named Polypore, who Jackson took for himself and enslaved on his Hermitage plantation.31

The fort’s elimination did not end the Black maroon war. The vast majority of the estimated 1,000 Black maroons at Prospect Bluff had escaped in advance of the Americans to the Suwannee where they were reported to be “training for vengeance.”32 Others left farther south to Angola, a growing Black maroon community below Tampa Bay, where they maintained contact with Woodbine and received British aid. Likewise, their nightmare of American slave raids and military incursions was far from over.33 While Clinch’s official report provided a divine justification for the massacre, another American participant wrote a more descriptive alternative account of the massacre that didn’t involve God:

The explosion was awful, and the scene horrible beyond description. You cannot conceive, nor I describe the horrors of the scene. In an instant lifeless bodies were stretched upon the plain, buried in sand and rubbish, or suspended from the tops of the surrounding pines. Here lay an innocent babe, there a helpless mother; on the one side a sturdy warrior, on the other a bleeding squaw. Piles of bodies, large heaps of sand, broken guns, accoutrements, etc, covered the site of the fort. The brave soldier was disarmed of his resentment and checked his victorious career, to drop a tear on the distressing scene.34

This post is a revised excerpt from A People’s History of Florida 1513-1876: How Africans, Seminoles, Women, and Lower Class Whites Shaped the Sunshine State by Adam Wasserman. Read the free PDF.

Footnotes

- Sugden, John. “The Southern Indians in the War of 1812: The Closing Phase.” Florida Historical Quarterly 60 (Jan. 1982): 274-280; Mahon, John K. “British Strategy and Southern Indians: The War of 1812.” Florida Historical Quarterly 44 (April 1966): 286-290; Owsley Jr., Frank L. “British and Indian Activities in Spanish West Florida during the War of 1812.” Florida Historical Quarterly 46 (Oct. 1867): 115-119; Arsene Lacarriere Latour. Historical memoir of the war in West Florida and Louisiana in 1814-15: with an atlas. Philadelphia, PA: John Conrad and Co., 1816.

- Davy Crockett, A Narrative of the Life of Davy Crockett (Philadelphia: EL Carey and A Hart, 1834), 88.

- Saunt, New Order of Things, 270.

- Ibid. 278

- On the British occupation of Pensacola, see Nathaniel Millett, Maroons of Prospect Bluff (Gainesville: University of Florida, 2013), 48-73; Matthew J. Clavin, Aiming for Pensacola (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2015), 41-46; William S. Coker, Indian Traders of the Southeastern Spanish Borderlands: Panton, Leslie and Company and John Forbes and Company, 1783-1847 (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 1986), 283-289.

- Janes Landers, Atlantic Creoles in the Age of Revolution (Cambridge, Harvard University, 2010), page 124, 178-179, 184-185; “Letters of John Innerarity: The Seizure of Pensacola by Andrew Jackson, November 7, 1814.” Florida Historical Quarterly 9 (1930): 130.

- Millett, Maroons of Prospect Bluff, 57.

- “Letters of John Innerarity,” 130.

- ASPIA 1: 861

- Sugden, “The Southern Indians in the War of 1812,” 299.

- ASPFA 4: 552.

- ASPFA 4: 560.

- Wright Jr., J.L. “A Note on the First Seminole War as Seen by the Indians, Negroes, and Their British Advisers.” The Journal of Southern History 34 (Nov., 1968): 569-570.

- ASPFA 4: 551. 91.

- Simmons, Notices of East Florida, 75.

- “James Innerarity to John Forbes.” Florida Historical Quarterly 12 (Jan. 1934): 129-130.

- Williams, John L. A View of West Florida. Philadelphia: H.S. Tanner, 1827. 96-102.

- ASPFA 4: 561.

- Ibid. 499, 555.

- Ibid. 561

- Ibid. 552

- Ibid. 555-556

- Savannah Journal, June 26, 1816, cited in Aptheker, Herbert. American Negro Slave Revolts. New York, NY: International Publishers, 1983. 31.

- Letter from the Secretary of War, Transmitting, Pursuant to a Resolution of the House of Representatives, of the 26th Ult. Information in Relation to the Destruction of the Negro Fort, in East Florida, in the Month of July, 1816. Washington: E. De. Krafft, 1819. 10-11.

- Ibid. 17

- ASPFA 4: 558.

- Forbes, James Grant. Sketches, historical and topographical, of the Floridas, more particularly of east Florida. 1821. Ed. with intro. James W. Covington. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 1964. 202.

- Ibid. 200-202.

- Ibid. 203-204.

- McMaster, John B. A History of the People of the United States: From the Revolution to the Civil War Vol. 4. New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1895. 433-434; “Letters of John Innerarity and A. H. Gordon.” Florida Historical Quarterly 12 (July 1933) 38-42.

- Landers, Atlantic Creoles, 184, 191-192.

- ASPMA, 1, 681-682.

- For a detailed account of the Angola community, see Canter Brown, Jr., “Sarrazota, or runaway Negro plantations”: Tampa Bay’s First Black Community,” Tampa Bay History 12 (Fall-Winter): 5-19;

- Army and Navy Chronicle. 13 vols. Washington: B. Homans, 1835-1842. Vol. 2, 115; Hereafter cited as A&NC.

Read more about this event in A People’s History of Florida.

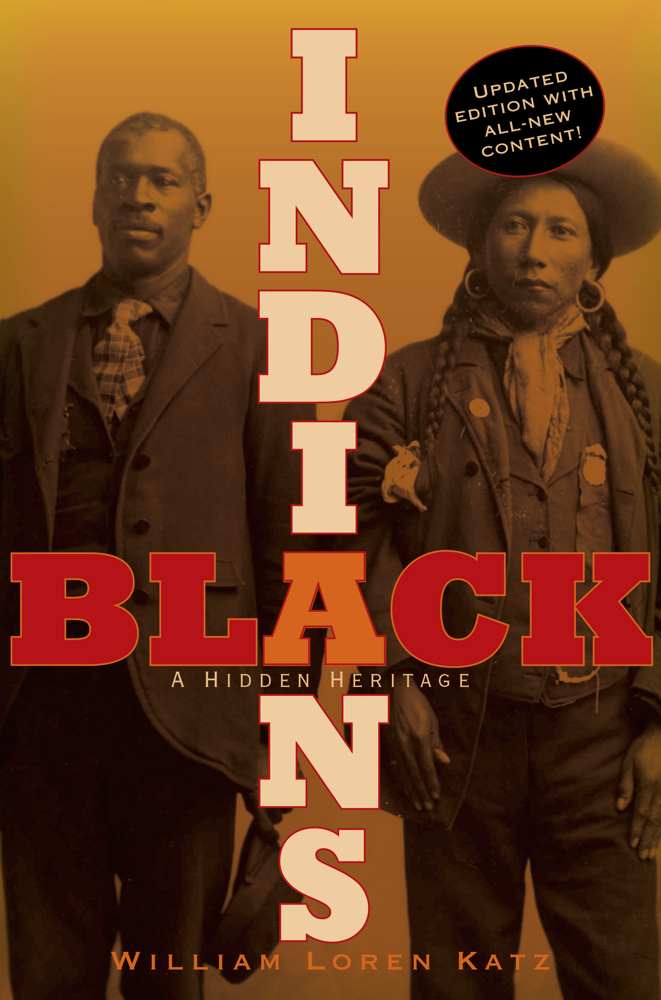

Students can learn more about this entire period of U.S. history in the book for grades 6+ called Black Indians: A Hidden Heritage.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn