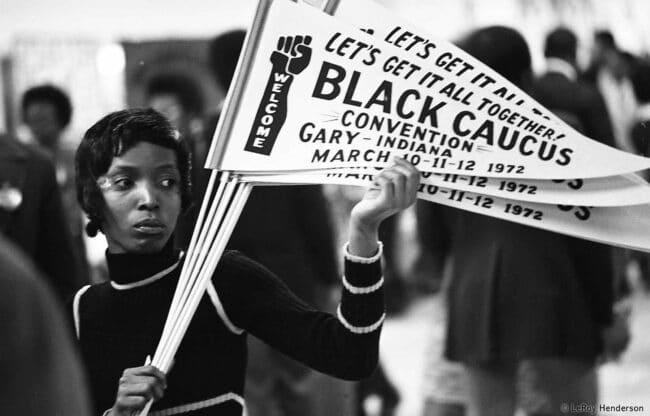

A woman holds pennants at the National Black Political Convention in Gary, Indiana in 1972. (c) LeRoy Henderson, used here with permission.

The first National Black Political Convention (NBPC) was held in Gary, Indiana on March 10, 1972. Approximately 8,000 people (including 3,000 delegates) gathered to create a political agenda to address the burning issues of the time.

Vincent Harding wrote in Hope and History,

One of the signal characteristics of the African American freedom movement has been its basic resiliency, its capacity to recover from harsh blows, to persevere against literally murderous pressures. The story of the National Black Political Convention in Gary, Indiana, in 1972 is another example of that vitality. This important gathering of African Americans took place amidst the repression and subversion, while the mourners’ songs continued to echo in our hearts. And yet Gary was still able to evoke and embody the persistent African American search for a creative tension between our calling as the prime keepers of the flame of American democracy and our responsibility to create and develop independent visions and institutions that nourish the Black community. If students can understand — indeed, feel and appreciate — that tension, they may learn the difference between racial solidarity and racial separatism.

Perhaps a study of Gary on film and in some of its documents will help us to recognize the vision of a new society that continued to emerge out of all the terrors of the old. For instance, it might be helpful to share with our students portions of a document that became the basis for many of the convention’s statements on the necessity of independent Black political organizing. For many people of that time saw such empowering Black organizing as a prerequisite not only for Black life here, but for the advancement of democracy and the transformation of the American nation as a whole.

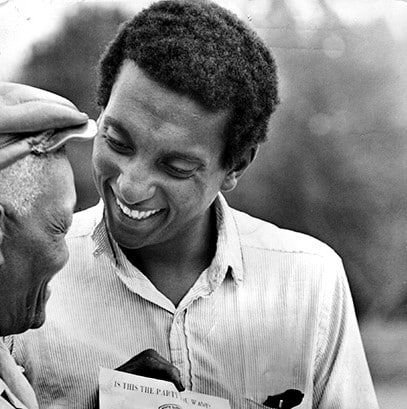

1972 National Black Political Convention in Gary, Indiana. Richmond mayor Henry Marsh is holding the Virginia sign. (c) LeRoy Henderson, used here with permission.

Here is a description of that historic convening, excerpted from “Tired of Going to Funerals:” The 1972 National Black Political Convention in Gary by Nicole Poletika for the Indiana History Blog.

Approximately 3,000 official delegates and 7,000 attendees from across the United States met at Gary’s West Side High School from March 10 to March 12. The attendees included a prolific group of Black leaders, such as Reverend Jesse Jackson, Coretta Scott King, Amiri Baraka, Muslim leader Minister Louis Farrakhan, Black Panther co-founder Bobby Seale, and Malcolm X’s widow Betty Shabazz. Organizers sought to create a cohesive political strategy for Black Americans by the convention’s end. . . .

Black poet and activist Amiri Baraka (formerly LeRoi Jones) advocated for the gathering to practice “unity without conformity.”

According to an essay in Major Problems in African American History, the Gary convention was the culmination of a series of uprisings in protest of discrimination, which historians refer to collectively as the Black Revolt. Black Americans were emboldened by tragic events, such as the assassination of Malcolm X in 1965, as well as legislative progress, like the Voting Rights Act of 1965. In an interview, North Carolina convention delegate Ben Chavis recalled:

I had gotten tired of going to funerals. . . . so much of the Movement had been tragic. You know. And I have to emphasize [Rev. Martin Luther] King’s assassination was a tragic blow to the Movement. And so four years later, March of ’72, for us to be gathering up our wherewithal to go to Gary, Indiana — hey, that was a good shot in the arm for the Movement.

State delegations, national organizations, and individuals proposed resolutions in the creation of “A National Black Agenda” (Muncie Evening Press). This agenda would extend the movement beyond the convention. As convention attendee and Distinguished Lecturer at York College City University of New York Dr. Ron Daniels noted, the Black Agenda was “integral to holding candidates, who would seek Black votes, accountable to the interests and aspirations of Black people.”

Delegates from Illinois suggested fines and prison sentences for businessmen found guilty of discriminatory practices. North Carolina attendees proposed a bill of prisoners’ rights that included humane treatment and fair trials. Delegates from Indiana and other states demanded that the U.S. dedicate resources to the plight of black Americans rather than the Vietnam War and end the conflict immediately. North Carolina representatives also urged that black men receive Social Security benefits earlier than white men since their life expectancy was eight years shorter. The Muncie Evening Press noted that “Politicking was intense . . . as state delegations tried to compromise their own views with positions they felt other delegations could support.” Tensions ran so high that part of the Michigan delegation walked out of the convention. [Continue reading at the Indiana History Blog.]

We also recommend reading A 1972 Black political convention offers a road map for fighting climate change: Climate change is a civil rights issue. Addressing it is essential to the survival of Black Americans by Ashley Farmer in The Washington Post (March 2022).

Students in New Jersey are studying the Gary Convention. Read Students Address Racial Justice at “Model Gary” Convention in Rethinking Schools.

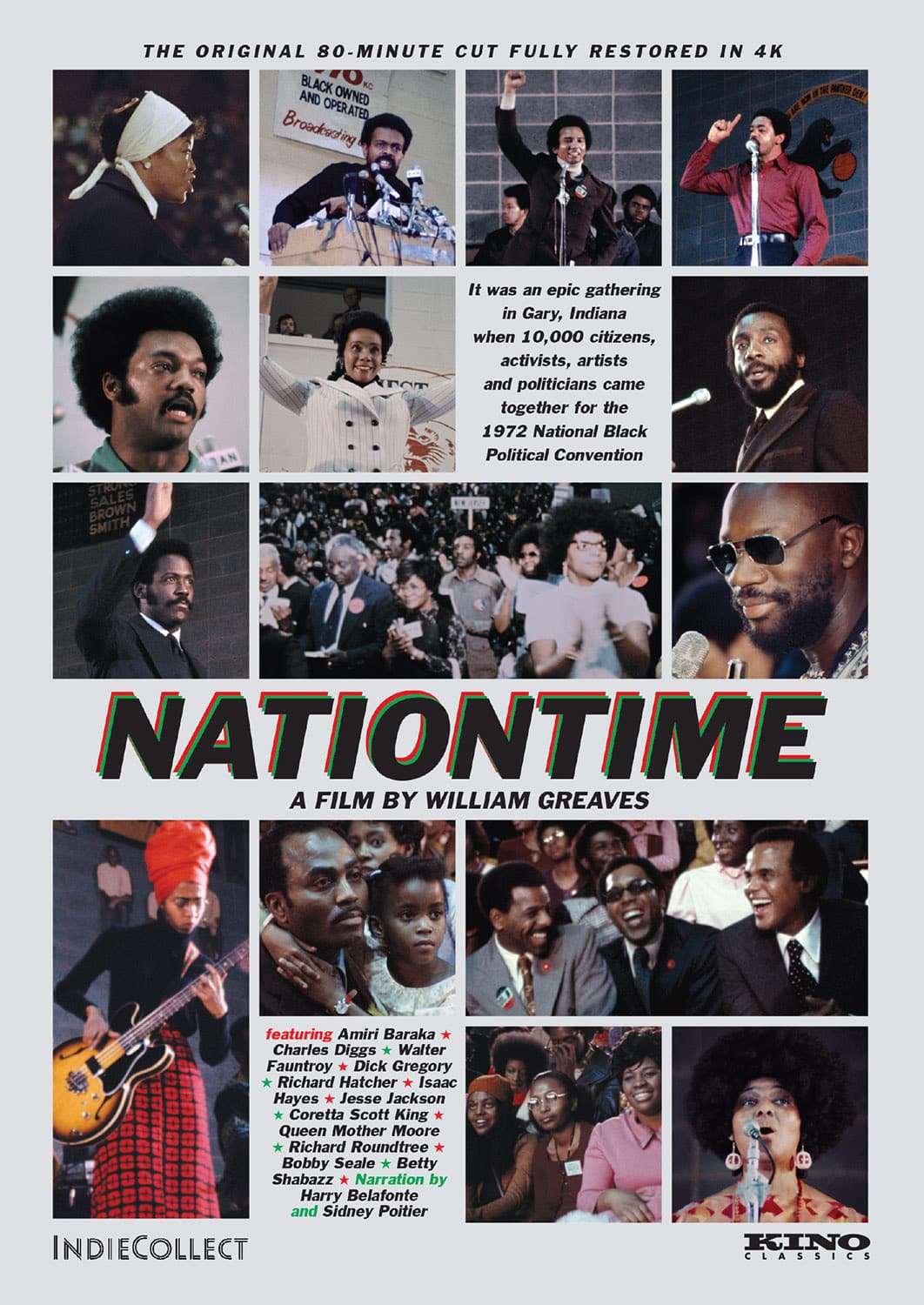

Documentary: Nationtime

Watch the 80 minute documentary, Nationtime, directed by William Greaves.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn