When will men for sake of peace

And for democracy

Learn no bombs a man can make

Keep men [and women] from being free?. . .

And this he says, our Harry Moore,

As from the grave he cries:

No bomb can kill the dreams I hold,

For freedom never dies!

— from “Ballad of Harry T. Moore” by Langston Hughes

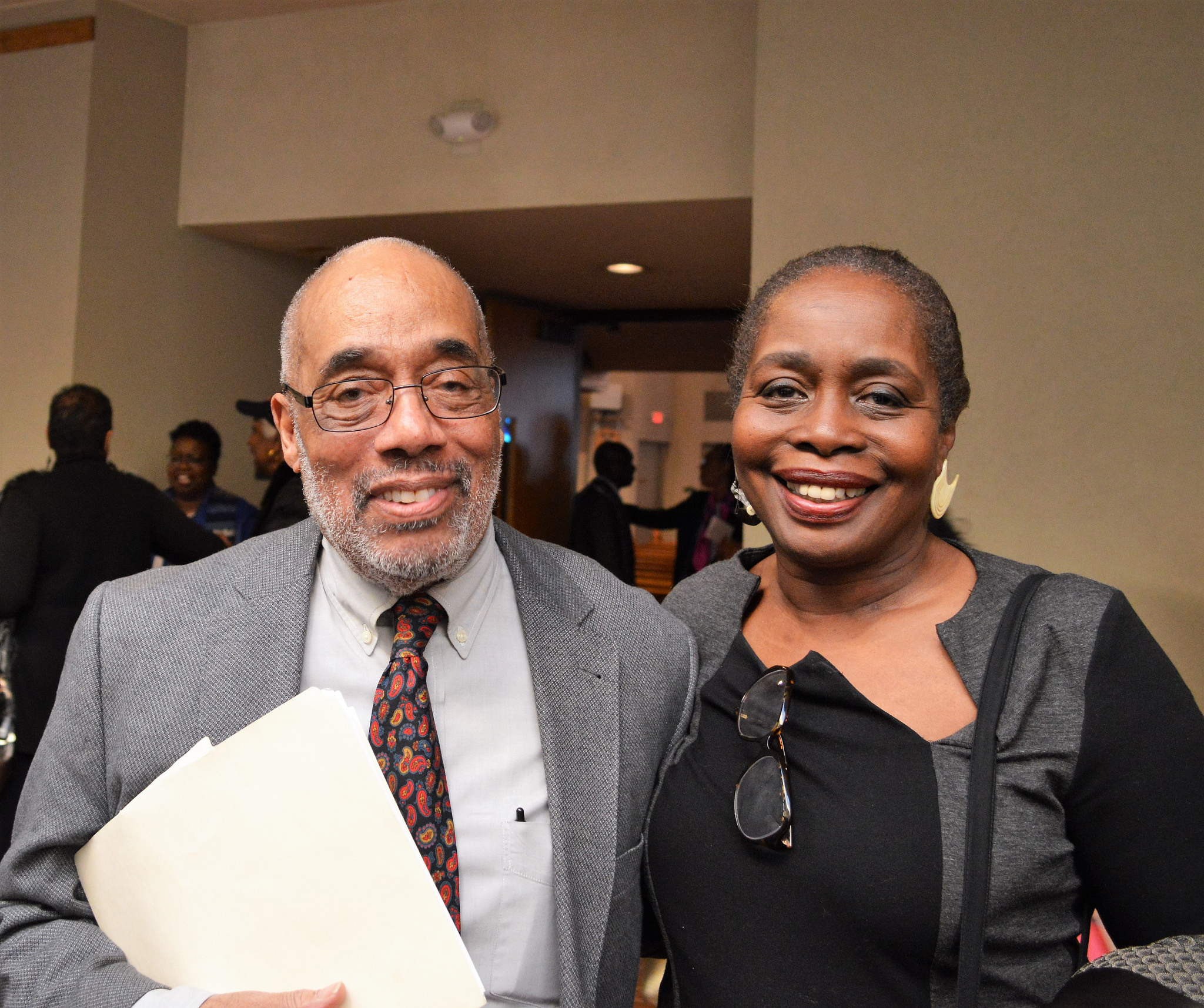

Harriette and Harry Moore with their two daughters.

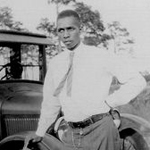

Harry T. and Harriette Moore were murdered on Christmas Day (their silver anniversary) when a bomb, set by the Klan, blew up their home in Mims, Florida. Harriette Moore was a classroom teacher and both were civil rights activists. Harry Moore died on the way to the hospital; Harriette Moore died nine days later, leaving behind two daughters, Evangeline and Annie Rosalea. Evangeline Moore dedicated her life to seeking justice for the death of her parents.

Background

From the Civil Rights Movement Archive.

Back in the 1930s, Harry and Harriette Moore began organizing for the NAACP in central Florida. They launched a legal struggle that eventually won equal pay for Black and white teachers. In 1941, Harry became President and later executive director of the Florida state NAACP. Under their leadership, the NAACP eventually grew to more than 10,000 members in more than 60 branches across the state.

In 1944, Thurgood Marshall won Smith v. Allwright in the U.S. Supreme Court which ruled that “all-white” primary elections are unconstitutional.

With Blacks now allowed to vote in the real elections, the Moore’s organized the Progressive Voters League of Florida and Harry became its President. Florida’s voter registration procedures were not as restrictive as those of neighboring Georgia and Alabama, and within a few years the Moores managed to register over 100,000 Black voters, increasing Black registration from 5% to 31% of those eligible. Their slogan was “A Voteless Citizen is a Voiceless Citizen.”

For years, Harry traveled Florida’s muddy backroads and poorly paved highways building the NAACP, helping Blacks register, and organizing the Voters League.

Harriette Moore was a 6th grade teacher at George Washington Public School. Paij Wadley Bailey shares a memory from her classroom in 1951.

Mrs. Moore did not complain or express outrage at having to teach us from old, tattered textbooks passed down to us from the white school. What she did do was teach us primarily from the few boxes of her own private books which she kept hidden under her desk.

Her books were about African-American people who had made important contributions to the world — people like W. E. B. Du Bois and Mary McLeod Bethune. Mrs. Moore taught us about the freedom fighters Harriet Tubman and Sojourner Truth. She read stories to us by Zora Neale Hurston and poems by Langston Hughes, and she shared her Ebony Magazine articles about Black history.

This learning was deep and personal; it was important because it was about people like us, and it was secret.

She didn’t have to tell us not to tell anyone about these books. We knew they were dangerous when she appointed one of us to be a look-out person at the window so if the Superintendent of Schools came on one of his unannounced inspections, he wouldn’t catch us using them.

These books — their physical existence and the stories they told — taught me about unspoken truths, secrets, and lies.

In addition to voter registration and education, the Moore’s investigated lynchings.

“Harriette and Harry T. Moore” painting by political prisoner Marius Mason. Source: supportmariusmason.org

In 1949, four young Black men (Groveland Four) were accused of raping a white girl in Lake County near Orlando — at that time a Klan stronghold. Later evidence indicates that the 17-year-old girl had been beaten by her husband, and that they concocted a phony rape story to conceal the beating from her parents who had threatened to shoot him if he brutalized her again.

Charles Greenlee (age 16), and war veterans Sam Shepherd and Walter Irvin, were arrested for the supposed rape. The fourth man, Ernest Thomas managed to flee, but was gunned down by a Sheriff’s posse a few days later. A mob of more than 500 white men assembled to lynch the remaining three. When they couldn’t locate the prisoners, they formed a caravan of 200 cars and descended on the Black neighborhood of Groveland where the families of the accused men lived. They shot into homes and set some on fire. The Florida Governor sent the National Guard to restore order.

Willis McCall, the Sheriff of Lake County, was notorious for his brutality against Blacks. Year-after-year he was reelected with the support of the citrus growers who he supplied with cheap, chain-gang prison labor at harvest time by arresting Blacks on trumped up charges for minor crimes. He also chased any and all union organizer out of the county.

The Moore’s discover that while in McCall’s custody, the three Groveland defendants were brutally beaten and made to stand on broken glass with their hands roped to a pipe over their heads. Despite this torture, they refused to confess to a crime they did not commit. Unable to force a confession, McCall’s deputies manufactured enough phony evidence to convince an all-white jury. Shepherd and Irvin were sentenced to death, 16-year old Greenlee was sentenced to prison.

Greenlee chose not to appeal out of fear that a new trial would result in a death sentence. Franklin Williams, Shepherd and Irvin’s NAACP attorney, appealed their conviction and it was overturned by the Supreme Court in 1951.

In November of 1951, Sheriff McCall removed the two men from prison. While driving them to Lake County for their new trial, he shot them, killing Shepherd and severely wounding Irvin. He claims that the two handcuffed and manacled prisoners attacked him while trying to escape.

When Irvin recovered enough to speak, he described how McCall pulled his car off the road, dragged the two men out, and began firing. The Moores demanded that McCall be suspended from office and indicted for murder. No charges were ever brought against McCall.

With the mob attack on Groveland, the original rape trial, the successful appeal, and the shootings fanning the flames of racism, Harry Moore was called “the most hated Black man in Florida.” His mother, visiting for the holidays, voiced concern for the Moores’ safety. Harry told her, “Every advancement comes by way of sacrifice. What I am doing is for the benefit of my race.”

Late in the night on Christmas Eve, 1951, a bomb exploded under Harry and Harriette’s bedroom. He died on the way to the hospital, she died of her injuries nine days later.

Text excerpted from Murder of Harry & Harriette Moore at Civil Rights Movement Archive.

Learn More

|

Harry T. and Harriette Moore BiographyWritten by students at DeLaura Junior High School to fill the gap in the textbooks. The students explain in this 1995 essay: The Moores’ battle for equality continues today. A step towards that goal is the rightful and long overdue recognition of the Moores in our schools history books. We, the students at DeLaura Junior High School therefore dedicate this supplementary history book to Mr. and Mrs. Moore. The Moores were not violent people, but people who did not let the fear of financial or bodily harm control their lives. The fear that kept them going, was that if they did not stand up and speak out that nothing would ever change. Because of their valiant efforts, changes have been made for the better. They are true heroes and an inspiration to us all. |

|

Freedom Never Dies: The Legacy of Harry T. Moore (PBS, 2001)This documentary is about the life of Harry Moore and the history of racism and resistance in Jim Crow era Florida. Narrated by Ossie Davis and Ruby Dee. Sweet Honey in the Rock and Toshi Reagon perform original music. Order from Documentary Educational Resources. See film clip below. |

|

The Ballad of Harry MoorePoem by Langston Hughes from The Collected Poems of Langston Hughes, edited by Arnold Rampersad and David Roessel (Alfred A. Knopf, 1995). Bernice Johnson Reagon turned the ballad into a song, performed by Sweet Honey in the Rock on the CD The Women Gather (Earth Beat, 2003). |

|

At Christmas, Evangeline Moore thinks of her martyred parents and demands justiceAn article in The Washington Post (Dec. 26, 2011) by Avis Thomas-Lester about the struggle of Evangeline Moore for justice for those responsible for murdering her parents. |

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn