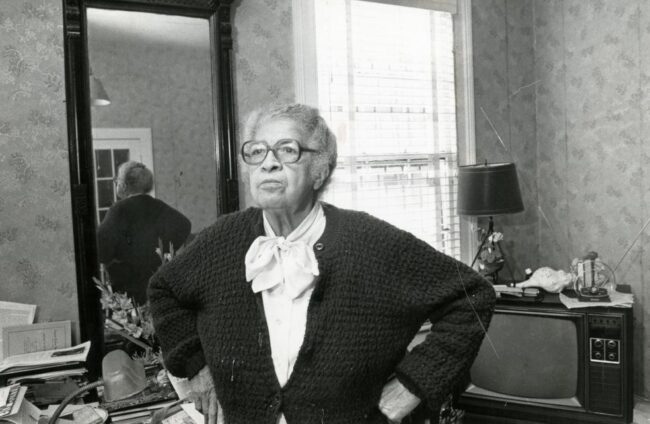

Modjeska Monteith Simkins at her home, 1984. Source: The State Newspaper Photograph Collection, Richland Library

On April 17, 1944, South Carolina civil rights advocate Modjeska Monteith Simkins wrote a letter to Governor Olin D. Johnston of South Carolina challenging him to a debate on white supremacy.

The debate was prompted by South Carolina’s all-white political primary system, a system in which Black voters, like Simkins, were systematically excluded from participating. Specifically, a special session of the state’s legislature had recently passed a series of 147 laws that further solidified political parties as all-white institutions. These laws were passed out of fear that the Supreme Court ruling in Texas earlier in 1944 that struck down these practices would affect the status of white supremacy in South Carolina. At the special session on April 14th, Governor Johnston made the following proclamation:

It now becomes absolutely necessary that we repeal all laws pertaining to primaries in order to maintain White supremacy in our Democratic primaries in South Carolina. After these statutes are repealed, we will have done everything within our power to guarantee white supremacy in our primaries of our state insofar as legislation is concerned. Should this prove inadequate, we South Carolinians will use the necessary methods to retain white supremacy in our primaries and to safeguard the homes and happiness of our people.

In an oral history interview, Simkins reflected,

Even though the Supreme Court had given us the right, these cats started making up new rules that you couldn’t vote. We had to continue wrangling around here because they didn’t intend to do anything but run the business like it is a white man’s country.

Simkins learned how to effectively use her voice for change at an early age. Her mother, Rachel Hull Monteith, was a leading figure in W. E. B. Du Bois’s Niagara Movement, and Simkins grew up attending many of the meetings. In 1941, after serving as the director of Negro Work for the South Carolina Tuberculosis Association for ten years, Simkins accepted a position as the secretary of the South Carolina State Conference of the NAACP.

It was in this position that Simkins wrote the letter challenging Governor Johnston to a debate on white supremacy. Her letter begins:

According to certain of your public statements which have been brought into high relief very recently in connection with the Special Session of the General Assembly of South Carolina, you hold that the mere fact of being born of white parents transcends all other human values, that all white men and all white women are superior to all men and women of color simply because they are not born white. And there are thousands in South Carolina who think just as you do. But it happens that I do not agree in the least with you and your constituency on this thing you call “white supremacy.”

She concluded that if he did not respond:

It could be considered clear evidence that you have conceded that ‘white supremacy’ is a myth for which neither sensible nor scientific bases can be found.

Although Governor Johnson never responded to Simkins’ letter, the all-white primary system was eventually struck down in 1947 by Judge Waties Waring in the Elmore v. Rice case. Simkins and the NAACP used the momentum following this victory to help register Black voters in the state. According to Simkins,

We had a big registration campaign as soon as we had the decision against the primary. We registered 150,000 people, enough to turn a politician wrong-side outwards.

To read Simkins’s full letter and learn more about her life, see the “Modjeska Monteith Simkins: A South Carolina Revolutionary” booklet created by Becci Robbins and the S.C. Progressive Network Education Fund.

This story was prepared by Emma Haseley.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn