Wheeling newspaper. Source: Ohio County Public Library.

On Feb 9, 1950, Wisconsin Senator Joseph McCarthy delivered a speech at the McLure Hotel in Wheeling, West Virginia during which he claimed to hold a list of known communists (“enemies from within”) in the U.S. State Department.

The speech grabbed national headlines and launched the paranoia and persecution now known as McCarthyism.

Howard Zinn described this event in Chapter 16 of A People’s History of the United States:

World events right after the war [WWII] made it easier to build up public support for the anti-Communist crusade at home. . . It was a general wave of anti-imperialist insurrection in the world, which would require gigantic American effort to defeat: national unity for militarization of the budget, for the suppression of domestic opposition to such a foreign policy. Truman and the liberals in Congress proceeded to try to create a new national unity for the postwar years — with the executive order on loyalty oaths, Justice Department prosecutions, and anti-Communist legislation.

In this atmosphere, Senator Joseph McCarthy of Wisconsin could go even further than Truman. Speaking to a Women’s Republican Club in Wheeling, West Virginia, in early 1950, he held up some papers and shouted: “I have here in my hand a list of 205 — a list of names that were made known to the Secretary of State as being members of the Communist Party and who nevertheless are still working and shaping policy in the State Department.”

The next day, speaking in Salt Lake City, McCarthy claimed he had a list of fifty-seven (the number kept changing) such Communists in the State Department. Shortly afterward, he appeared on the floor of the Senate with photostatic copies of about a hundred dossiers from State Department loyalty files. The dossiers were three years old, and most of the people were no longer with the State Department, but McCarthy read from them anyway, inventing, adding, and changing as he read. In one case, he changed the dossier’s description of “liberal” to “communistically inclined,” in another form “active fellow traveler” to “active Communist,” and so on.

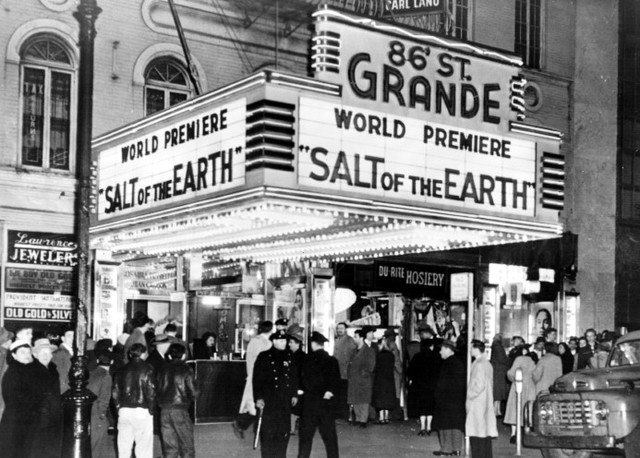

McCarthy kept on like this for the next few years. As chairman of the Permanent Investigations Sub-Committee of a Senate Committee on Government Operations, he investigated the State Department’s information program, its Voice of America, and its overseas libraries, which included books by people McCarthy considered Communists. The State Department reacted in panic, issuing a stream of directives to its library centers across the world. Forty books were removed, including The Selected Works of Thomas Jefferson, edited by Philip Foner, and The Children’s Hour by Lillian Hellman. Some books were burned.

McCarthy became bolder. In the spring of 1954 he began hearings to investigate supposed subversives in the military. When he began attacking generals for not being hard enough on suspected Communists, he antagonized Republicans as well as Democrats, and in December 1954, the Senate voted overwhelmingly to censure him for “conduct . . . unbecoming a Member of the United States Senate.” The censure resolution avoided criticizing McCarthy’s anti-Communist lies and exaggerations; it concentrated on minor matters — on his refusal to appear before a Senate Subcommittee on Privileges and Elections, and his abuse of an army general at his hearings.

The full chapter of A People’s History of the United States is worth reading, as it goes on to talk about the House Un-American Activities Committee and more.

Roy Cohn

Roy Cohn, who served as a chief counsel to Senator Joseph McCarthy during the Red Scare in the 1950s and would later become a leading mob attorney. Cohn represented Trump for years and once claimed he considered Trump to be his best friend. Cohn is the subject of a 2019 documentary titled “Where’s My Roy Cohn?” We highly recommend this Democracy Now! interview with the film’s director, Matt Tyrnauer.

Reflection Questions

Here are some suggested questions for reflection on the topic of McCarthyism:

What was the intended/actual impact of the McCarthy attacks on the labor movement and the Civil Rights Movement?

What was the role of the media and why?

Is the McCarthy era really an era or do we still live with McCarthyism today?

Below are resources for teaching about McCarthyism and the Red Scare, including a textbook critique and classroom lesson.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn