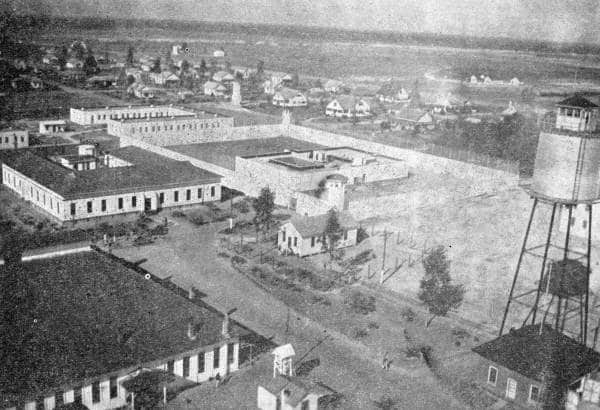

On April 11, 1993, Easter Sunday, incarcerated men at Ohio’s “supermax” prison — Southern Ohio Correctional Facility, commonly called Lucasville — launched an uprising that lasted for 11 days. The 450 or so incarcerated people who participated in the uprising were of diverse races, religions, and gang-affiliations, yet they all came together for their shared interest. The Lucasville Uprising remains one of the longest prison uprisings in U.S. history.

Martha Grevatt writes for Workers World,

The uprising began as Muslim inmates protested against being forced to take a tuberculosis test that violated their religious beliefs against alcohol. It quickly turned into a full-scale rebellion that left a guard and several inmate hostages dead. The uprising ended with prison authorities agreeing to a list of 21 demands.

Later the authorities scapegoated a group of 50 inmates, giving most of them harsh sentences of 5 to 25 years and sending five to death row, including the prisoner leaders who had negotiated the peaceful surrender. The five — Siddique Abdullah Hasan, Keith Lamar (aka Bomani Shakur), James Were (aka Namir Mateen), Jason Robb, and George Skatzes — remain on death row.

Hostage negotiators, Dirk Prise (seated) and Highway Patrol Sgt. Howard Hudson, left, meet in the Southern Ohio Correction Facility yard with prisoner Stanley Cummings, right, and prison guard James Anthony Demons, second from right, for a live television broadcast where the prisoner listed the demands of inmates holding hostages in the prison. Source: The Columbus Dispatch

Historian Staughton Lynd, who along with his wife Alice became ardent supporters of those sentenced for organizing the uprising, wrote,

The five prisoners from the rebellion on death row — the “Lucasville Five” — are a microcosm of the rebellion’s united front. Three are Black, two are white. Two of the Blacks are Sunni Muslims. Both of the whites were, at the time of the rebellion, members of the Aryan Brotherhood.

On the 30th anniversary of the Lucasville Uprising in 2023, former political prisoner Eric King (who was incarcerated at the time), wrote,

Source: Freedom Archive

What the Lucasville uprisers had was bravery, dignity, and a collective mindset that what would come was worth it to stand up for themselves. Organizing any level of resistance inside prison is incredibly difficult. Imagine the bravery of the Lucasville revolters. They knew with 100 percent certainty that whatever comforts, family contact, and safety they felt was absolutely finished. They knew death was a possibility, either at the hands of self-serving prisoners looking to settle scores or at the more likely hands of the cops who would be acting with rage-fueled impunity. They had the foresight to know and accept that there would be extreme brutality now and the chance for dignified treatment in the future. They played the long game with the hopes of feeling human and being treated as such.

The Lucasville Five remain on death row in Ohio for their involvement in the Lucasville Uprising, though several refute these charges.

Additional Resources

Lucasville: The Untold Story of a Prison Uprising by Staughton Lynd (PM Press)

Siege in Lucasville (Revised Edition) by Gary Williams (1st Library Books)

“After 25 Years…,” Two Perspectives on the Lucasville Prison Uprising, a podcast interview with inside and outside people involved in the Lucasville Uprising on the Final Straw Radio

Overcoming Racism: the Lucasville Rebellion by Staughton Lynd

Overcoming Racism: the Lucasville Rebellion by Staughton Lynd

Lucasville Legacy: A Historic, Deadly Prison Riot Prompted Changes in Ohio’s Lockups by Jo Ingles, Daniel Konik, and Karen Kasler at The Statehouse News Bureau

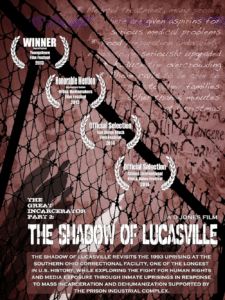

The Great Incarcerator, part 2: The Shadow of Lucasville, a 2013 documentary by D. Jones

Learn more in the Democracy Now! interview below, where Amy Goodman speaks with Staughton Lynd about the Lucasville Uprising and the hunger strike of those still being held in solitary confinement.

This post was written by the Certain Days: Freedom for Political Prisoners Calendar collective, which is an educational and fundraising project founded in 2001 to raise awareness and funds for political prisoners held in North America. The collective was formed by Black Liberation Army political prisoners Herman Bell and Robert Seth Hayes and white anti-imperialist political prisoner David Gilbert — all of whom have since gained their freedom after decades of incarceration — and outside supporters.

This post was written by the Certain Days: Freedom for Political Prisoners Calendar collective, which is an educational and fundraising project founded in 2001 to raise awareness and funds for political prisoners held in North America. The collective was formed by Black Liberation Army political prisoners Herman Bell and Robert Seth Hayes and white anti-imperialist political prisoner David Gilbert — all of whom have since gained their freedom after decades of incarceration — and outside supporters.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn