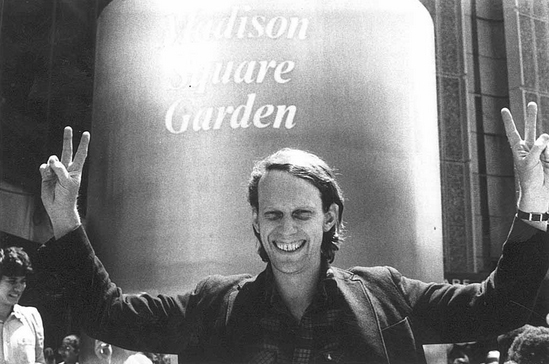

Sam Lovejoy at the 1979 No Nukes Concert at Madison Square Garden. Source: Montague Retreat Center.

In the wee morning hours of February 22, 1974, Sam Lovejoy, a member of one of the local communes near Montague, Massachusetts, slipped onto the Montague Plains and sabotaged the 500 foot weather tower Northeast Utilities had erected to test wind direction at the site. (A company official later explained that the data was needed so that authorities would know which way the radiation would blow from the plant in case of an accident.)

Using a few simple farm tools to loosen the turnbuckles in the stays of the tower, Lovejoy left behind him 349 feet of twisted wreckage. He then ran to the nearest road, flagged down a passing patrol car, and got a ride to the Turners Falls station, where he gave Officer Donald Cade the news. In a typed four-page statement, he said:

As a farmer concerned about the organic and the natural, I find irradiated fruit, vegetables and meat to be inorganic; and I can find no natural balance with a nuclear plant in this or any community.

There seems to be no way for our children to be born or raised safely in our community in the very near future. No children? No edible food? What will there be?

While my purpose is not to provoke fear, I believe that we must act; positive action is the only option left open to us. Communities have the same rights as individuals. We must seize back control of our own community.

The nuclear energy industry and its support elements in government are practicing actively a form of despotism. They have selected the less populated rural countryside to answer the energy needs of the cities. While not denying the urban need for electrical energy (perhaps addiction is more appropriate), why cannot reactors be built near those they are intended to serve? Is it not more efficient? Or are we witnessing a corrupt balance between population and risk?

It is my firm conviction that if a jury of twelve impartial scientists was empaneled, and following normal legal procedure they were given all pertinent data and arguments, then this jury would never give a unanimous vote for deployment of nuclear reactors amongst the civilian population. Rather, I believe they would call for the complete shutdown of all the commercially operated nuclear plants.

Through positive action and a sense of moral outrage, I seek to test my convictions.

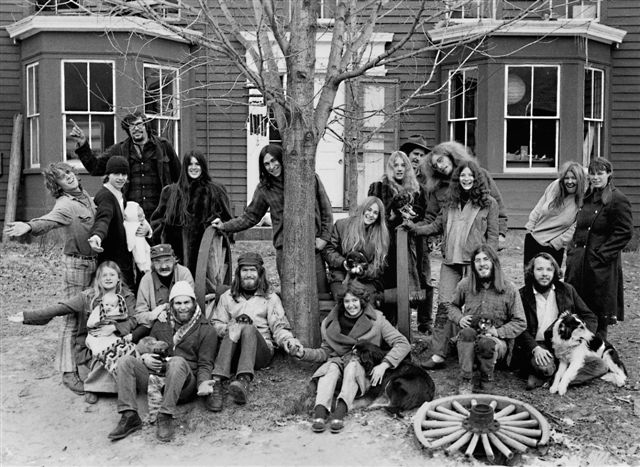

Montague farm commune. Source: Peter Simon.

A long-time resident of the town and the Valley, Lovejoy was freed that morning on personal recognizance. Later he was indicted on one count of wanton and malicious destruction of personal property, which carried a possible five-year sentence. He pleaded “absolutely not guilty” and announced he would handle his own defense. The trial would begin in six months.

Lovejoy’s tower-toppling received national attention, but its most important effect was on the immediate area where “nuke” suddenly became a household word. Area newspapers were beginning to fill with stories about atomic energy, and local car bumpers began to sprout a crop of blue-and-white stickers that said “No Nukes” and bore a circle with two wavy lines inside, the astrological sign of Aquarius. The symbol, said organizers, was for natural energy.

Lovejoy’s trial began, and he brought in two experts: Dr. John Gofman, a member of the Manhattan Project, and Howard Zinn as an expert on civil disobedience.

Lovejoy’s trial began, and he brought in two experts: Dr. John Gofman, a member of the Manhattan Project, and Howard Zinn as an expert on civil disobedience.

The brunt of Gofman’s testimony centered on plutonium, on which he had done much pioneer research. Gofman told the court that, in the Atomic Energy Commission’s phrase, plutonium is “the most fiendishly toxic substance ever known.” Three tablespoonfuls, he said, could cause nine billion human cancers. But each nuclear plant creates thousands of pounds of waste plutonium, and there’s no way to store it. “The proliferation of nuclear power carries with it the obligation to guard the radioactive garbage . . . not only for our generation but for the next thousand or several thousand.”

Gofman’s concluding testimony had enormous impact on the local community:

Some awfully big interests invested in uranium and the future of atomic power. And unfortunately their view is “We’ve got to recover our investment, no matter what the cost to the public.”

Under questioning from Lovejoy, Zinn told the court that the tower-toppling was in the best tradition of Gandhi, Thoreau, and the Abolitionists, including (of course) Elijah P. Lovejoy, Sam’s distant cousin, who was murdered by a pro-slavery mob in southern Illinois. Judge Smith interrupted to ask if true civil disobedience didn’t demand both strict nonviolence and the acceptance of lawful punishment. Zinn replied that the destruction of property was not violent when life was at stake. “Violence,” he said, “has to do with human beings, not property.”

Zinn pointed out that Lovejoy had turned himself in, whereas many civil disobedients disappear rather than stand trial. Judge Smith seemed much taken with Zinn, and constantly interrupted him with questions. A good third of what Zinn said was in the form of colloquy with the judge. At one point Smith asked leave for a private conversation with the witness, and leaned over to talk quietly. Zinn said later the judge had asked to meet him for dinner sometime.

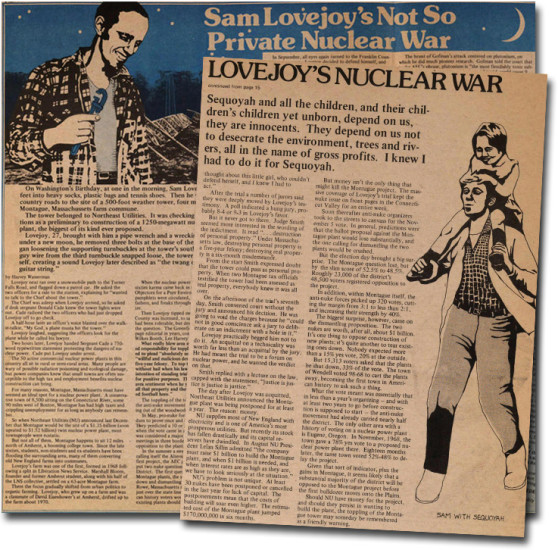

Next Lovejoy took the stand and talked to the jury for six hours about his life and conversion to sabotage, without objection from the prosecution. The last hour was an intensely emotional narration of his final decision to topple the tower, how he acted not out of malice “but because I had fallen in love with a little four-year-old girl named Sequoya. I asked myself, who am I to do this thing, to take on the role of judge. But then I thought about this little girl who couldn’t defend herself, and I knew I had to act.”

After the trial several jurors said they were deeply moved by Lovejoy’s testimony. A poll indicated a hung jury, at least eight to four or nine to three in Lovejoy’s favor. Much would have depended on Judge Smith’s directions, which might have been favorable on the malice question. But it never got that far. There was another aspect to the indictment, and it read “destruction of personal property.” Under Massachusetts law, destroying personal property is a felony punishable by five years in prison; destroying real property is a six month misdemeanor. The prosecution wanted Sam behind bars for five years, not just six months.

Smith had expressed doubt all along that the tower could pass as personal property. It was worth $42,500, nobody disputed that. But when Lovejoy produced two Montague tax officials who testified the tower had been assessed as real property, and when Murphy called a Northeast Utilities official who affirmed under cross-examination that the tax had been paid as real property, everyone knew it was all over. So, after lunch on Yom Kippur Eve, Smith convened court, again with the jury sent out, and announced his decision. He was going to void the charge because he “could not in good conscience ask a jury to deliberate on an indictment with a hole in it.”

Lovejoy practically begged him not to do it. He had meant the trial to test the issue of nuclear power, and he wanted his guilt or innocence to be determined on that issue, by the jury and “the people of Franklin County.” Smith replied with a lecture on the law. “Justice is justice is justice is justice” he concluded.

Then he called in the jury, ordered them to stand and render a verdict of “Not guilty.” He then dismissed the court. The crowd was as stunned as the jurors were relieved. The following day, Northeast Utilities announced their decision to put off construction of the nuclear plants for another year due to financial issues, and eventually cancelled the project in 1980.

Adapted from “The Story of Samuel Lovejoy” by Harvey Wasserman originally printed in WIN magazine.

Film Clip: Lovejoy’s Nuclear War by Green Mountain Post Films

Includes interviews with community members and their thoughts about Lovejoy’s action, Sam Lovejoy about trial strategy, Dr. John Gofman on why he is testifying at Lovejoy’s trial and the importance of the nuclear power issue, and Howard Zinn on civil disobedience.

Watch the full documentary on YouTube.

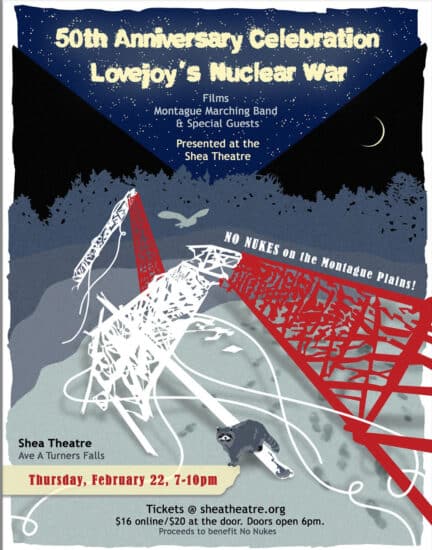

In 2024, on the 50th anniversary, Shea Theater held a Celebration of Lovejoy’s Nuclear War film screening followed by a Q&A. Below is the poster from that event.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn