By Leon A. Waters

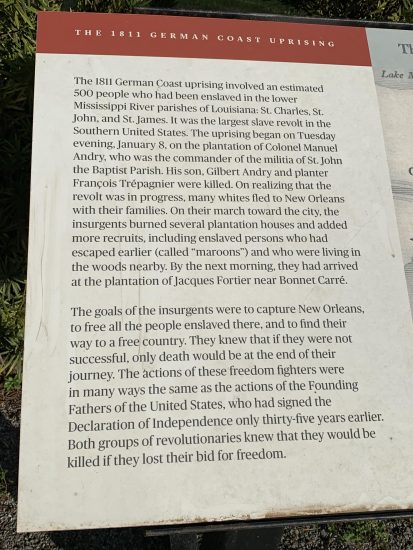

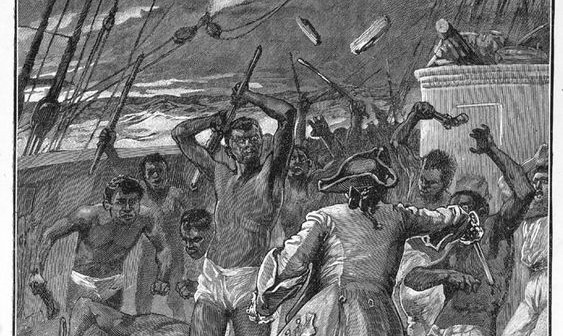

One of the most suppressed and hidden stories of African and African American history is the story of the 1811 Slave Revolt. The aim of the revolt was the establishment of an independent republic, a Black republic. Over 500 Africans, from 50 different nations with 50 different languages, would wage a fight against U.S. troops and the territorial militias.

This revolt would get started in St. John the Baptist and St. Charles parishes, about 30 miles upriver from New Orleans. At that time, New Orleans was the capital of what was called the Orleans Territory. The revolt sought to capture the city of New Orleans and make New Orleans the capital of the new republic.

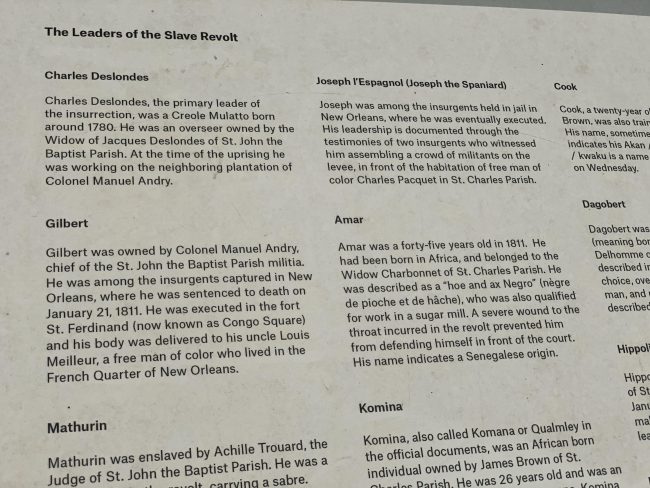

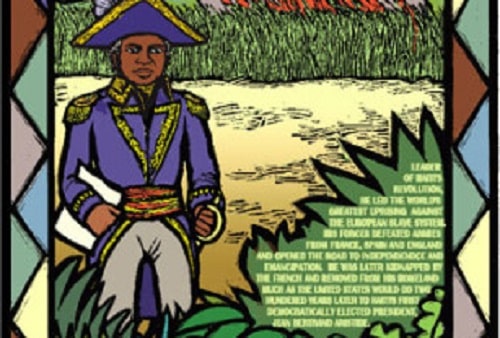

The principal organizer and leader of this revolt was a man named Charles, a laborer on the Deslonde plantation. The Deslonde family had been one of the many San Domingo slave holding families that fled the Haitian Revolution (1790-1802). The Deslonde family fled to Louisiana for refuge. In their escape, the Deslonde family brought their chattel property, Charles and others, with them.

The Deslonde family acquired land and restarted their slave holding sugarcane operations in St. John the Baptist parish. The ideas of slave rebellion had been inspired by the Haitians’ defeat of Napoleon and his allies, who included President George Washington. The victory of Africans in gaining their freedom in Haiti had a powerful and stimulating effect on Africans held in bondage all over the world, especially in the Western Hemisphere. It gave enormous encouragement to the Africans on plantations in Louisiana. To capture the city of New Orleans, Charles Deslonde’s strategy consisted of a two-pronged military assault.

One prong of the attack would be to march down the River Road to New Orleans. The rebels would gain in number as they moved from plantation to plantation on the East Bank of the Mississippi River from St. John the Baptist parish to New Orleans. They were intent on creating a slave army, capturing the city of New Orleans and liberating the tens of thousands of slaves held in bondage in the territory of Louisiana.

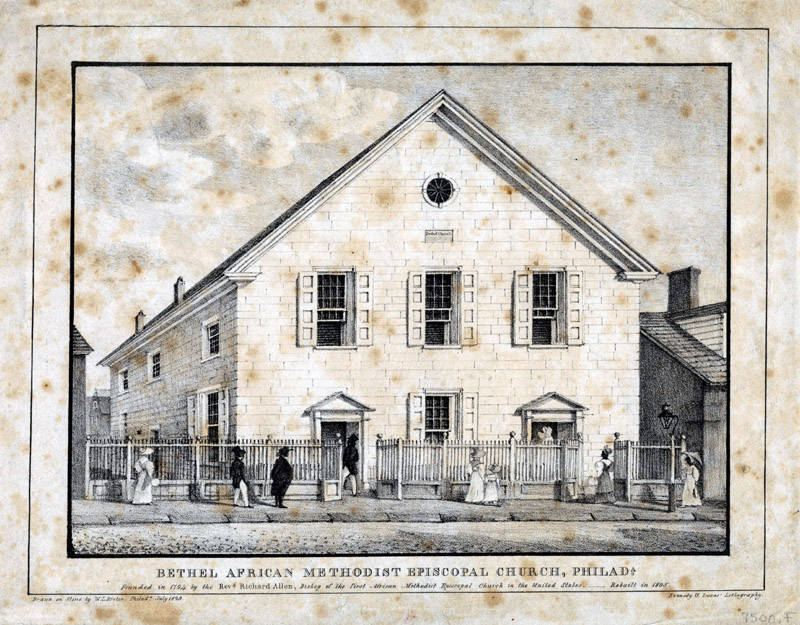

The other prong of attack was to involve the enslaved Africans inside the city of New Orleans in a simultaneous uprising. Here the rebels would seize the arsenal at Fort St. Charles and distribute the weapons to the arriving slave army. The two-pronged attack would then merge as one and proceed to capture the strategic targets in the city.

On the evening of Jan. 8, 1811, Charles and his lieutenants would start the revolt. The rebels would elect their leaders to lead them into battle. They elected women and men. The leaders were on horseback. Several young warriors marched ahead of them with drums and flags. Men and women assembled in columns of four behind those on horseback.

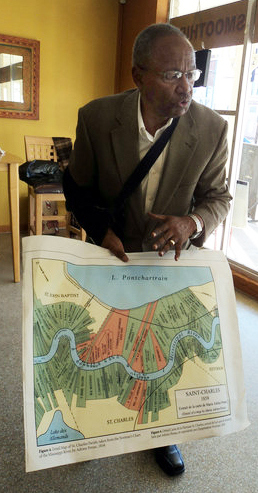

Author and historian Leon Waters speaks on the 1811 Slave Revolt. He is descended from the rebels. Photo: San Francisco Bay View

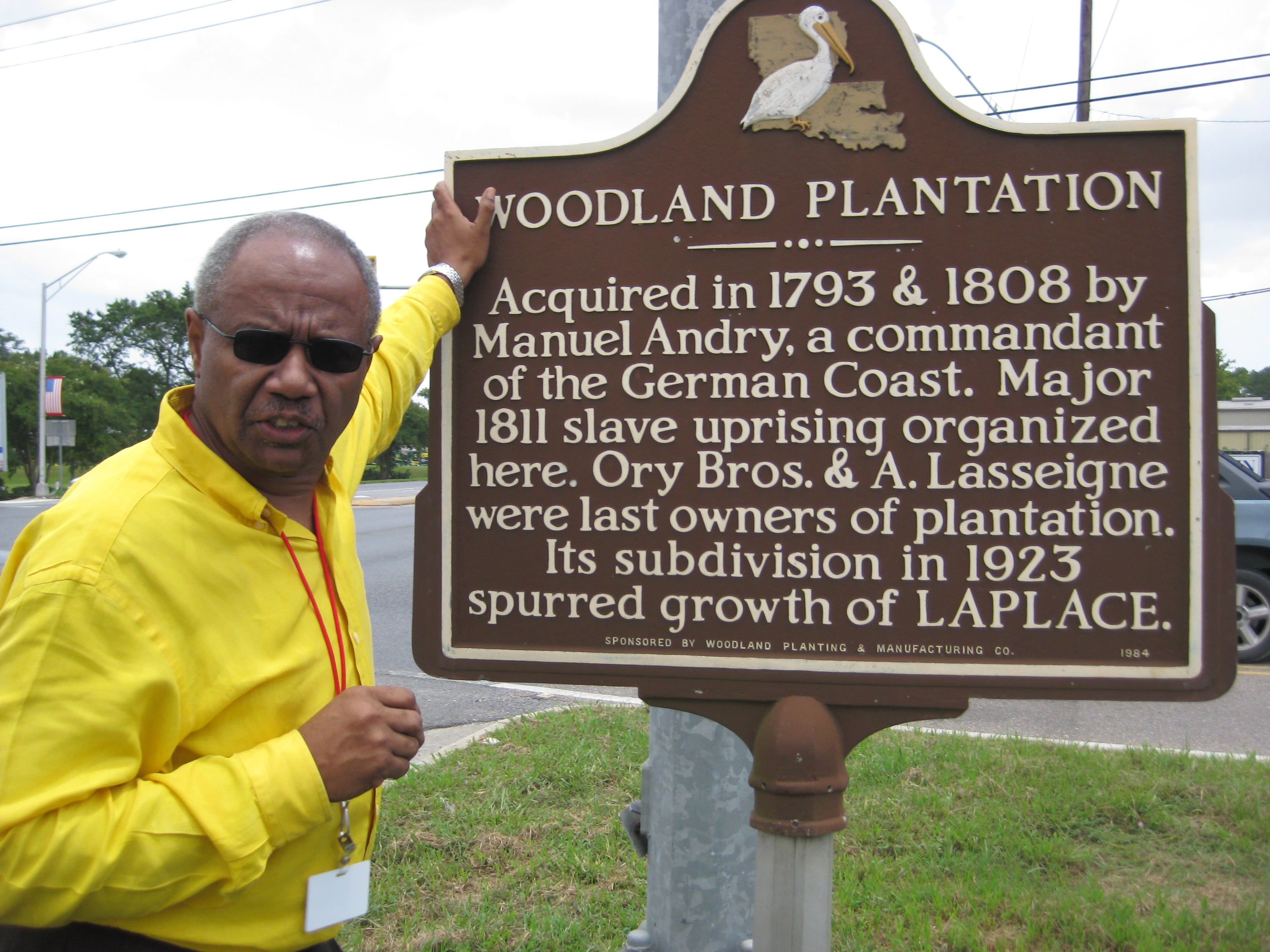

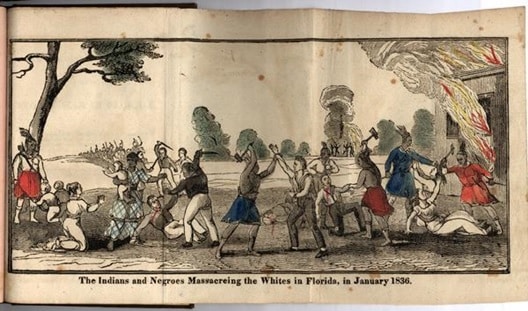

The rebels rose up on the plantation of Col. Manuel Andry (today the city of LaPlace) in St. John the Baptist Parish. They overwhelmed their oppressors. Armed with cane knives, hoes, clubs and a few guns, the rebels marched down the River Road toward New Orleans. Their slogan was “On to New Orleans” and “Freedom or Death,” which they shouted as they marched to New Orleans.

However, despite their best efforts, they were not able to succeed. The revolt was put down by Jan. 11 and many of the leaders and participants were killed by the slave owners’ militia and U.S. federal troops. Some of the leaders were captured, placed on trial and later executed. Their heads were cut off and placed on poles along the river in order to frighten and intimidate the other slaves. This display of heads placed on spikes stretched over 60 miles.

The sacrifices of these brave women and men were not in vain. The revolt reasserted the humanity and redeemed the honor of the people. The uprising weakened the system of chattel slavery, stimulated more revolts in the following years and set the stage for the final battle, the Civil War (1861-1865) that put an end to this horrible system. The children and the grandchildren of the rebels of 1811 finished the job in the Civil War. Louisiana contributed more soldiers — over 28,000 — to the Union Army than any other state.

These women and men of 1811 represented the best qualities of people of African descent. They were people of exceptional courage, valor and dedication. These were women and men who put the interest and welfare of the masses above their own personal desires. These were people who understood that the emancipation of the masses is a precondition for the emancipation of the individual.

The sacrifices of these brave women and men were not in vain. The revolt reasserted the humanity and redeemed the honor of the people.

Remember the Ancestors! Remember the women and men who carried out the largest African uprising on American soil.

Author and historian Leon A. Waters, publisher and manager of Hidden History Tours, chairman of the Louisiana Museum of African American History and descendant of the 1811 rebels, can be reached at leonawaters8@gmail.com.

This article was originally published by the San Francisco Bay View on July 1, 2013, and republished with the author’s permission.

The photos below are from a memorial at the Whitney Plantation (outside of New Orleans). They were sent to us by journalist Melinda Anderson who visited on the anniversary of the uprising, Jan. 8, 2019. We highly recommend taking a trip to the Whitney Plantation. It places the stories of the majority of the people who lived and worked there front and center. (Click each image for a larger version.)

|

|

|

|

Slave Rebellion Reenactment is a community-engaged artist performance and film production that, on November 8-9, 2019, reimagined the German Coast Uprising of 1811. Envisioned and organized by artist Dread Scott and documented by filmmaker John Akomfrah. Read more at The Guardian and see video clip below.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn