On March 17, 1856, the Virginia General Assembly responded to lobbying from slaveholders and human traffickers by making it harder for enslaved African Americans to escape on ships and by increasing penalties for anyone helping such freedom-seekers.

The comprehensive legislation required thorough inspections of all vessels leaving Virginia ports, offered $100 rewards to anyone who caught freedom-seekers aboard the ships, mandated five-to-ten-year prison sentences for free African Americans who assisted escapees and rewarded $500 to anyone who provided information that resulted in the conviction of a “white person engaged in carrying off a slave, or in any manner concerned in helping an escape.”

The comprehensive legislation required thorough inspections of all vessels leaving Virginia ports, offered $100 rewards to anyone who caught freedom-seekers aboard the ships, mandated five-to-ten-year prison sentences for free African Americans who assisted escapees and rewarded $500 to anyone who provided information that resulted in the conviction of a “white person engaged in carrying off a slave, or in any manner concerned in helping an escape.”

Virginia had been ratcheting up similar laws for decades but with limited results. The geography that made Virginia’s coast and riverfront cities successful in nautical commerce, including the slave trade, also made the state a center for maritime Underground Railroad activity. As historian Dr. Cassandra Newby-Alexander, dean of the Norfolk State University’s College of Liberal Arts, observes in Virginia Waterways and the Underground Railroad

It was along the thousands of miles of tidal rivers . . . that uncounted freedom seekers made their escape. These rivers were some of the most important water routes along the Atlantic Seaboard that earlier brought Africans to their fate as enslaved laborers. It is ironic that these rivers would also be part of a waterway network that took many to freedom.

Virginia’s legislation on March 17, 1856, came after years of complaints from enslavers and pro-slavery politicians, newspaper editors, and other complicit oppressors moaning about the loss of valuable “property.” Newby-Alexander reports: “Virginia senator James Mason estimated that Virginia lost an average of $100,000 worth of slave property annually. Based on some of the figures published in local Hampton Roads newspapers, this was a rather low estimate, given that the region was among the largest Underground Railroad embarkation points in Virginia.”

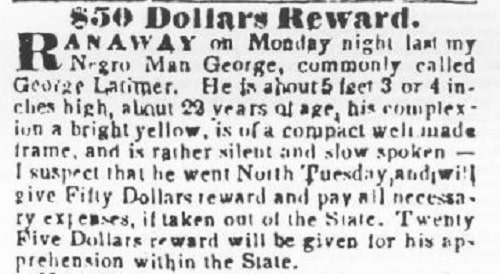

There were many remarkable escapes by boat. For example, in October 1842, George and Rebecca Latimer, expecting their first child, hid on a steamboat going to Boston. They wanted their children to be born free — and one of them grew up to be inventor Lewis Howard Latimer. Another was widow Susan Brooks, who walked onto the steamship City of Richmond with an ironed shirt over her arm as if delivering laundry. With the help of an onboard Underground Railroad conductor, she stayed hidden until reaching freedom in Philadelphia.

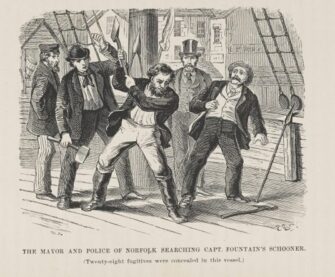

Wood engraving, 1879 edition, by Edmund B. Bensell. Source: University of Virginia Special Collections

Schooner Captain A. Fountain, noted as “Capt. F.” by Underground Railroad chronicler William Still, had multiple successes, included standing up to a pro-slavery boarding party led by Norfolk Mayor Ezra T. Summers in November 1855. The slavecatchers poked a shipment of wheat with spears and began chopping the ship’s deck with axes. Fountain took up an axe himself and told the mayor that he would join in chopping because his ship was already being destroyed. The mayor backed down to the relief of Fountain, his crew, and 21 freedom-seekers hidden below.

After the Virginia General Assembly enacted the tougher law, many ship captains and crew members were arrested or detained “but only a few received prison terms,” writes Newby-Alexander. She added that the flow of escapes continued “because of the dedication of those seeking freedom and those determined to assist.”

See Timothy D. Walker’s Sailing to Freedom: Maritime Dimensions of the Underground Railroad (University of Massachusetts Press) for more information.

By Michael Knepler, who prepares occasional #tdih posts for the Zinn Education Project.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn