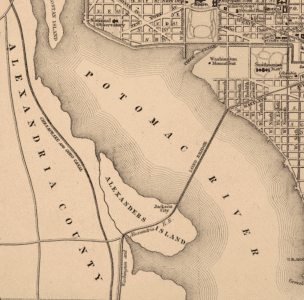

Kate Brown was violently assaulted when she tried to take her seat in the Washington & Alexandria Railway train’s ladies’ car (route pictured).

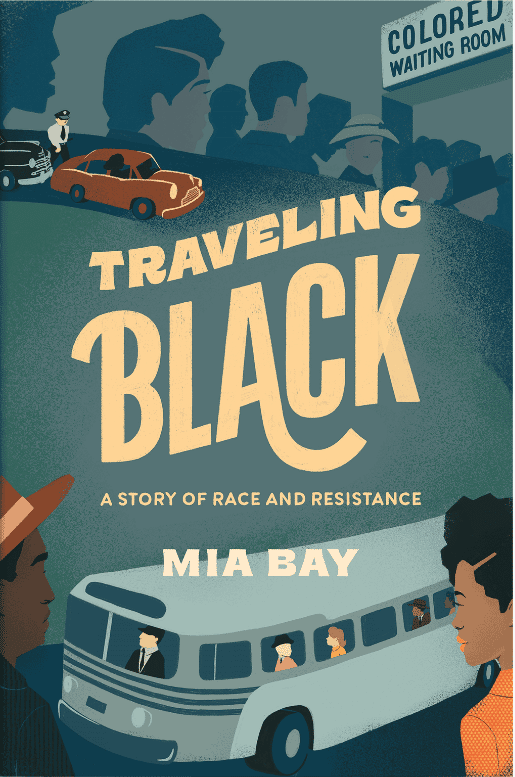

On February 8, 1868, 28-year-old Kate Brown was refused admission to the ladies’ car when she tried to travel on the Washington & Alexandria Railway. An employee of the U.S. Senate traveling from Alexandria, Virginia, to Washington, D.C., Brown stood firm when the private security officer on the train told her she was not permitted to ride on the ladies’ car on account of her race, being Black. Brown told the officer she paid for her ticket and would ride in the car she chose.

“I bought my ticket to go to Washington in this car . . . before I leave this car I will suffer death,” she said.

The Senate website offers “The Kate Brown Story,” explaining what happened next:

A violent altercation ensued. Reportedly, the police officers employed by the railroad physically ejected Brown from the train, throwing her onto the platform. Fortunately, another Senate employee, a committee clerk named B. H. Hinds, arrived on the scene. He accompanied the badly injured Brown back to Washington, where she sought medical treatment.

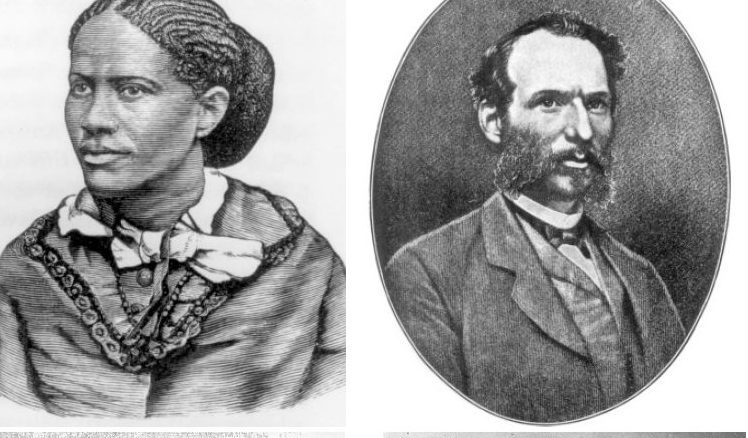

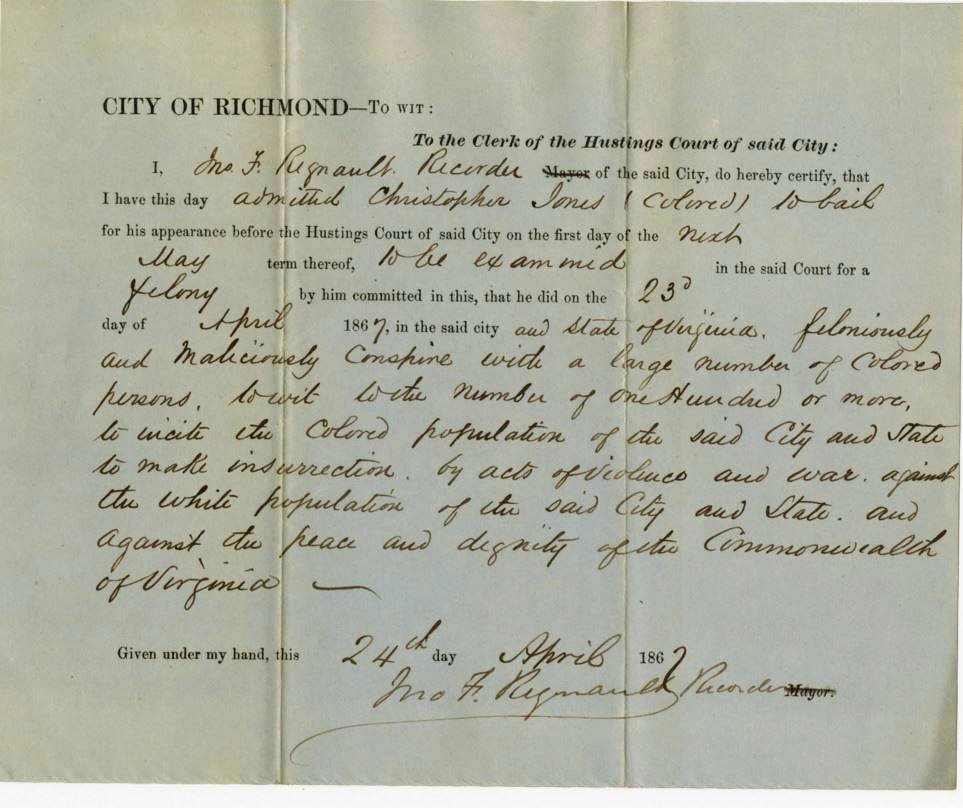

Upon hearing of the incident, Massachusetts senator Charles Sumner demanded that the Senate investigate this “outrage that has occurred within sight of [the] Capitol.” Senator Charles Drake of Missouri agreed. “It is an outrage upon an American woman,” he cried, “a citizen of the United States.” On February 10, Lot Morrill of Maine introduced a resolution to investigate. Later that month, Iowa senator John Harlan heard testimony from officials of the railroad company, from eyewitnesses, and from Brown’s doctor. Too badly injured to appear, Kate Brown gave her testimony from her sick bed.

Several months later, on June 17, the investigation released its findings (download PDF to read full Senate report) that were very favorable to Brown. She sued the railroad company. Legal arguments focused on the company’s right to segregate its cars. At the time, segregation was common on many railroads, but in this particular case it was illegal. The 1863 congressional charter authorizing the Washington & Alexandria Railway included — at the insistence of Charles Sumner — this key sentence: “That no person shall be excluded from the cars on account of color.”

Railroad officials argued that they complied with the charter by providing two separate but identical cars.

The Railroad lost and was forced to pay Brown $1,500 in damages. It made a “Separate but Equal” argument 28 years before it became Constitutional.

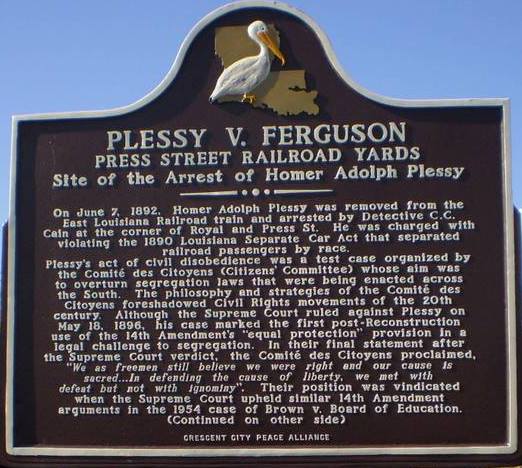

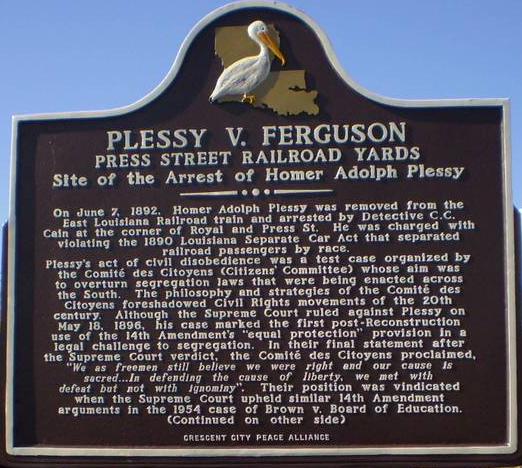

Kate Brown’s story illustrates the radical possibility of racial justice that the Reconstruction Era held. This happened before Plessy v. Ferguson decided Homer Plessy did not belong in the “white’s only” car and before the Jim Crow Era. Read more about this case through that lens in Kate Masur’s article, “Winning the Right to Ride: How D.C.’s streetcars became an early battleground for post-emancipation civil rights,” adapted from a portion of her book about racial equality in post-war Washington, D.C., An Example for All the Land.

Learn more in the Zinn Education Project national report, “Erasing the Black Freedom Struggle: How State Standards Fail to Teach the Truth About Reconstruction,” and find teaching resources on Reconstruction below.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn