Here is an excerpt from a powerful, day to day timeline (including July 22) by Bruce Hartford of organizing in Grenada, Mississippi in the summer of 1966. We recommend reading the full timeline and sharing it with students to get a sense of the bravery and tactics of local people during the Civil Rights Movement. The timeline also highlights the brutal threats faced by demonstrators and the role of the police in defending white supremacy, not the law.

Sunday, July 10. Small integrated groups attempt to attend services at some of the white churches. They are all refused entrance. Similar attempts are made on every following Sunday for many weeks. No white church ever allows a Negro inside to pray, nor are whites accompanying Negroes allowed inside.

A demonstration is held in front of the County Jail where those who were arrested on the night march of July 7 are still incarcerated. Since the parade ordinance bars marches, we “drift” there in small groups. About 50 demonstrators rally on the Jailhouse lawn with around 250 Negro onlookers watching from the sidelines. The action is ended when a large force of Mississippi state troopers begin to form up in riot gear behind the courthouse. By the time the troopers arrive we are on our way back to the church. Seeing no demonstrators to beat, the troopers attack the bystanders, hitting many with rifle butts. (As a general rule in Grenada, the troopers preferred to beat folk with their rifles, while the city cops and sheriffs favored the more traditional billy clubs.) A dozen or so bystanders are injured.

Monday, July 11. At the mass meeting that night, a “Blackout” (boycott) of all white merchants is announced to protest the beatings the day before, and to enforce the 51 demands of July 9.

Wednesday, July 13. A large picket line is sent downtown. All 45 are arrested for some reason that is never clearly explained or understood by anyone.

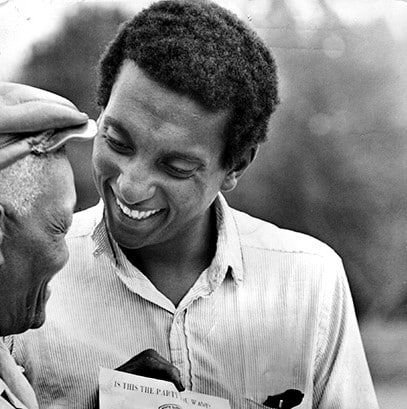

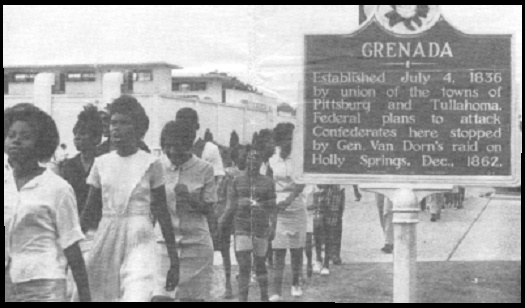

Mass rally on Grenada’s central town square, 1966.

Thursday July 14. In the heat of the afternoon, 220 marchers led by Hosea Williams of SCLC go uptown. We enter the town square and move on to the central green. When we get to the green we find ten Negro prisoners brought in from Parchman State Prison. They are protecting the Confederate Memorial statue — under orders to prevent us from touching it. We leave them alone knowing the terrible punishment that they will suffer if the statue is “violated,” or “desecrated” with another American flag.

After a rally on the green we march to the courthouse to try to register more voters. Sheriff Suggs Ingram refuses to let more than 3 people at a time into the courthouse. We refuse to let small groups go in alone because of the danger of intimidation and violence. This is the first march in Grenada since the Meredith March passed through that is allowed to complete without being blocked, arrested, or attacked by the police. . .

Friday, July 22. Federal Judge Claude Clayton issues a sweeping injunction ordering police to stop interfering with lawful protest, ordering police to protect our demonstrations, and requiring that we follow certain rules set down for the conduct of marches.

Saturday, July 23. The white community reacts in fury to the injunction. A large mob of angry whites, estimated at around 700 and reportedly including five carloads of Klansmen from Philadelphia, Mississippi (where Chaney, Schwerner, and Goodman were murdered), gather on the square to attack the night march. They are visibly armed with clubs, chains, and knives. We assume they also have hidden guns.

The Mississippi state troopers claim to be “caught by surprise” by this “sudden” hostile mob. They claim they don’t have enough men to protect the march, but if we cancel the march tonight they promise they will bring in reinforcements and protect the march on the following nights. We accept this, and do not march. When the whites discover that we are not going to march, they advance down Pearl and Cherry Streets to attack Bellflower church where we are having our mass meeting. The troopers block them.

Continue reading in “Grenada Mississippi — Chronology of a Movement” by Bruce Hartford at the Civil Rights Movement Archive website, CRMvet.org.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn