In Jackson, Mississippi on March 27, 1961, nine Tougaloo College students and members of the local Youth Council of the NAACP staged a sit-in to protest segregation at the Jackson Public Library. At the time, African Americans were prohibited from using the main library in Jackson, in accordance with Jim Crow laws prevalent throughout the South at the time.

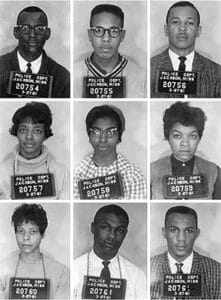

The nine students — Meredith Coleman Anding Jr., James Cleo Bradford, Alfred Lee Cook, Geraldine Edwards, Janice Jackson, Joseph Jackson Jr., Albert Earl Lassiter, Evelyn Pierce, and Ethel Sawyer — were trained in civil disobedience by Medgar Evers, the president of the Jackson branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) at that time.

Mugshot photos of the Tougaloo Nine, students protesting segregation at the Jackson, Mississippi public library. Source: Black Past

According to Black Past, this is how the sit-in progressed that day:

On March 27, 1961, the Tougaloo Nine began their protest by entering the Jackson Main Library. Typical of civil rights demonstrators of that era, the women wore dresses and the men wore shirts and ties. The Nine first visited the George Washington Branch (Colored) to request books they knew would not be in that facility. When they were told the books were not there, they went to Jackson Public Library where they attempted to stage a “read-in.” They sat at different tables across the library reading library books quietly. The librarian called the Jackson police who arrived and asked them to leave. When they did not, the nine were arrested, charged with of breach of the peace, and jailed.

Later that day, students from Jackson State College, a predominantly Black institution, organized a prayer vigil in support of the Tougaloo Nine. Hundreds of people attended the vigil which was broken up by Jackson State College president Jacob Reddix, who was backed by city police. Three students — Joyce and Dorie Ladner and student body president Walter Williams, who organized the prayer vigil — were expelled from Jackson State College for their support of the Tougaloo Nine.

On March 28, other Jackson State students boycotted classes in protest, held another rally, and marched to the Jackson City Jail where the nine were being held. They were joined by townspeople led by Medgar Evers. Jackson Police used tear gas and dogs against the protesters which included women and children. An 81-year-old man suffered a broken arm from an attack by a police officer with a nightstick. Evers’s supporters raised bail for the protesters who were arrested. They were later represented by local civil rights attorney Jack Harvey Young Sr.

The Tougaloo Nine went to trial on March 28, 1961 and were all found guilty of breach of the peace. Each student was sentenced to 30 days in jail and fined $100. The judge however suspended the sentences on the condition that there would be no further demonstrations. There were none. [Continue reading.]

Describing the trial, Sophia Gardner, Brie Thompson-Bristol and Kathy Roberts Forde write for the Washington Post article How the Tougaloo Nine Transformed History:

Two days after the library sit-in, the Tougaloo Nine faced trial. The courtroom was split down the middle, half Black and half White, and a line of 25 police officers and two German shepherds were stationed outside, ready to pounce at the first sign of “agitation.” When a crowd of Black supporters burst into applause as the Tougaloo students arrived outside the courthouse, the officers and dogs attacked. Medgar Evers took a pistol blow to the head, and many were clubbed and mauled.

The Nine were convicted of breaching the peace. The Jackson papers didn’t print a single word opposing police brutality against peaceful Black citizens. [Continue reading.]

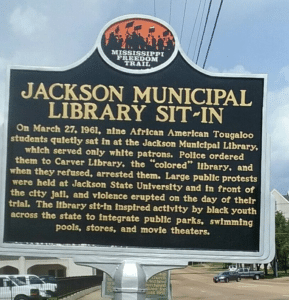

A historical marker commemorating the Tougaloo Nine and their sit-in to protest segregation. Source: Clarion Ledger

The Washington Post article concludes:

The work continues. In 2020 Tougaloo, responding to continued police brutality against Black Americans, established the Reuben V. Anderson Institute for Social Justice, named for an alumnus who graduated in 1964 and became the first Black justice on the Mississippi Supreme Court. As Myrlie Evers-Williams, the activist and widow of Medgar Evers, said, “The change of tide in Mississippi began with the Tougaloo Nine.” [Continue reading.]

Additional Resources

The Neglected Tale of the Tougaloo Nine and Their 1961 Read-In by Leah Rachel von Essen (Book Riot)

Black History Month: The Tougaloo Nine Try Integrating Local Library Through Read-In by Quentin Smith (WLBT3, Jackson, Mississippi)

The Desegregation of Public Libraries in the Jim Crow South: Civil Rights and Local Activism by Wayne A. Wiegand and Shirley A. Wiegand (LSU Press)

More stories of sit-ins at public libraries.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn