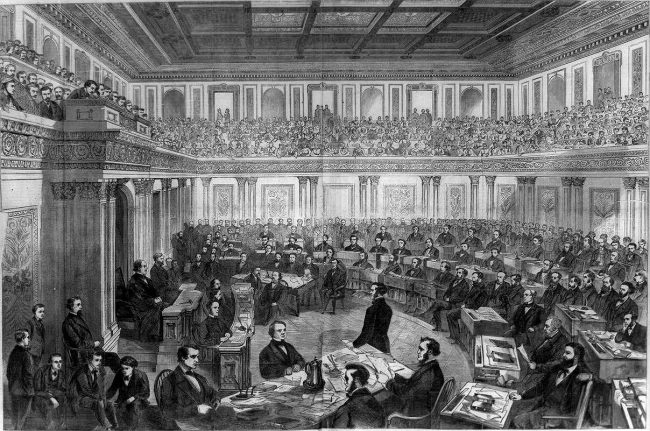

On March 5, 1868 the impeachment trial of President Andrew Johnson began in the Senate with U.S. Supreme Court Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase presiding.

W. E. B. Du Bois wrote in Black Reconstruction in America,

The transubstantiation of Andrew Johnson was complete. He had begun as the champion of the poor laborer, demanding that the land monopoly of the Southern oligarchy be broken up, so as to give access to the soil, South and West, to the free laborer. He had demanded the punishment of those Southerners who by slavery and war had made such an economic program impossible. Suddenly thrust into the Presidency, he had retreated from this attitude. He had not only given up extravagant ideas of punishment, but he dropped his demand for dividing up plantations when he realized that Negroes would largely be beneficiaries. Because he could not conceive of Negroes as men, he refused to advocate universal democracy, of which, in his young manhood, he had been the fiercest advocate, and made strong alliance with those who would restore slavery under another name.

This change did not come by deliberate thought or conscious desire to hurt — it was rather the tragedy of American prejudice made flesh; so that the man born to narrow circumstances, a rebel against economic privilege, died with the conventional ambition of a poor white to be the associate and benefactor of monopolists, planters and slave drivers. In some respects, Andrew Johnson is the most pitiful figure of American history. A man who, despite great power and great ideas, became a puppet, played upon by mighty fingers and selfish, subtle minds; groping, self-made, unlettered and alone; drunk, not so much with liquor, as with the heady wine of sudden and accidental success.

In A People’s History of the United States, Howard Zinn described the Reconstruction era events that led to the impeachment trial,

Congress passed a number of laws in the late 1860s and early 1870s . . .— laws making it a crime to deprive African Americans of their rights, requiring federal officials to enforce those rights, giving African Americans the right to enter contracts and buy property without discrimination. And in 1875, a Civil Rights Act outlawed the exclusion of African Americans from hotels, theaters, railroads, and other public accommodations.

With these laws, with the Union army in the South as protection, and a civilian army of officials in the Freedman’s Bureau to help them, southern African Americans came forward, voted, formed political organizations, and expressed themselves forcefully on issues important to them. They were hampered in this for several years by Andrew Johnson, Vice-President under Lincoln, who became President when Lincoln was assassinated at the close of the war.

Johnson vetoed bills to help African Americans; he made it easy for Confederate states to come back into the Union without guaranteeing equal rights to Blacks. During his presidency, these returned southern states enacted “black codes,” which made the freed people like serfs, still working the plantations. For instance, Mississippi in 1865 made it illegal for freedmen to rent or lease farmland, and provided for them to work under labor contracts which they could not break under penalty of prison. It also provided that the courts could assign black children under eighteen who had no parents, or whose parents were poor, to forced labor, called apprenticeships — with punishment for runaways.

Andrew Johnson clashed with Senators and Congressmen who, in some cases for reasons of justice, in others out of political calculation, supported equal rights and voting for the freedman. These members of Congress succeeded in impeaching Johnson in 1868, using as an excuse that he had violated some minor statute, but the Senate fell one vote short of the two-thirds required to remove him from office.

Historian Stephen West shares the history in a tweet thread.

1. Perhaps in a near drunken state, Andrew Johnson made a series of wild, rambling speeches before the 1866 mid-term elections.

He compared himself to Jesus. He suggested that a Congressman should be hanged as a traitor. He excused the racist violence of the New Orleans massacre

— Stephen West (@Stephen_A_West) June 26, 2018

Read the Zinn Education Project national report, “Erasing the Black Freedom Struggle: How State Standards Fail to Teach the Truth About Reconstruction,” and find teaching resources on Reconstruction below.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn