Inauguration of President Hayes, showing Senate wing of the U.S. Capitol and the crowd on the lawn before it, March 5, 1877. Source: Library of Congress

On March 4, 1877, Rutherford B. Hayes became President of the United States. His inauguration had been in dispute with a close election with Samuel Tilden. (The public inauguration was on the 5th because March 4 was a Sunday.)

Below are excerpts about the Compromise of 1877 that settled the election and its impact on Reconstruction from A People’s History of the United States by Howard Zinn and Black Power U.S.A.: The Human Side of Reconstruction 1867-1877 by Lerone Bennett Jr.

From Black Power U.S.A.: The Human Side of Reconstruction 1867-1877 (pages 379 – 380):

In this volatile situation, the business community and large sectors of the Northern public panicked. From the big Northern newspapers, from the boards of trade and chambers of commerce of New York, Pittsburgh, and Chicago came one unanimous cry: “Peace, peace at any price.”

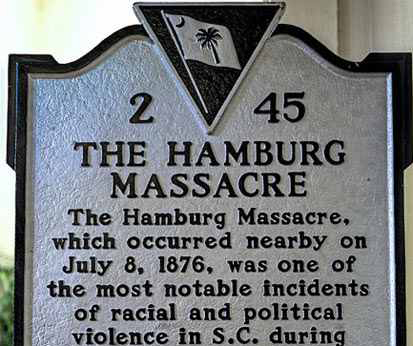

Congressman Lucien Bonaparte Casswell of Wisconsin summed up the spirit of the hour. “The members of Congress,” he said, “are of the impression that the people wish to revive business at any political sacrifice.” And what this meant in plain English was that the people demanded the sacrifice of the Black man and the letter and spirit of the Declaration of Independence.

The sacrifice was prepared at a series of meetings that began in December 1876, and continued through the spring of 1877, in three meetings between representatives of Hayes and white Southerners. The first two meetings were held in House and Senate committee rooms. The third meeting was held that night in the room of W. M. Evarts in the Wormley House, a posh D.C. hotel, owned, ironically, by a wealthy Black businessman.

At these meetings, Southerners promised to call off the filibuster, and Hayes’ representatives promised the South “Home Rule,” withdrawal of federal troops, and an increased allocation of economic resources. Incredible as it may seem now, this private agreement, which changed the course of American democracy, was reduced to writing. . . .

The agreement was signed and delivered, the filibuster was called off, and Rutherford B. Hayes was inaugurated as the 19th president of the United States on March 5, 1877.

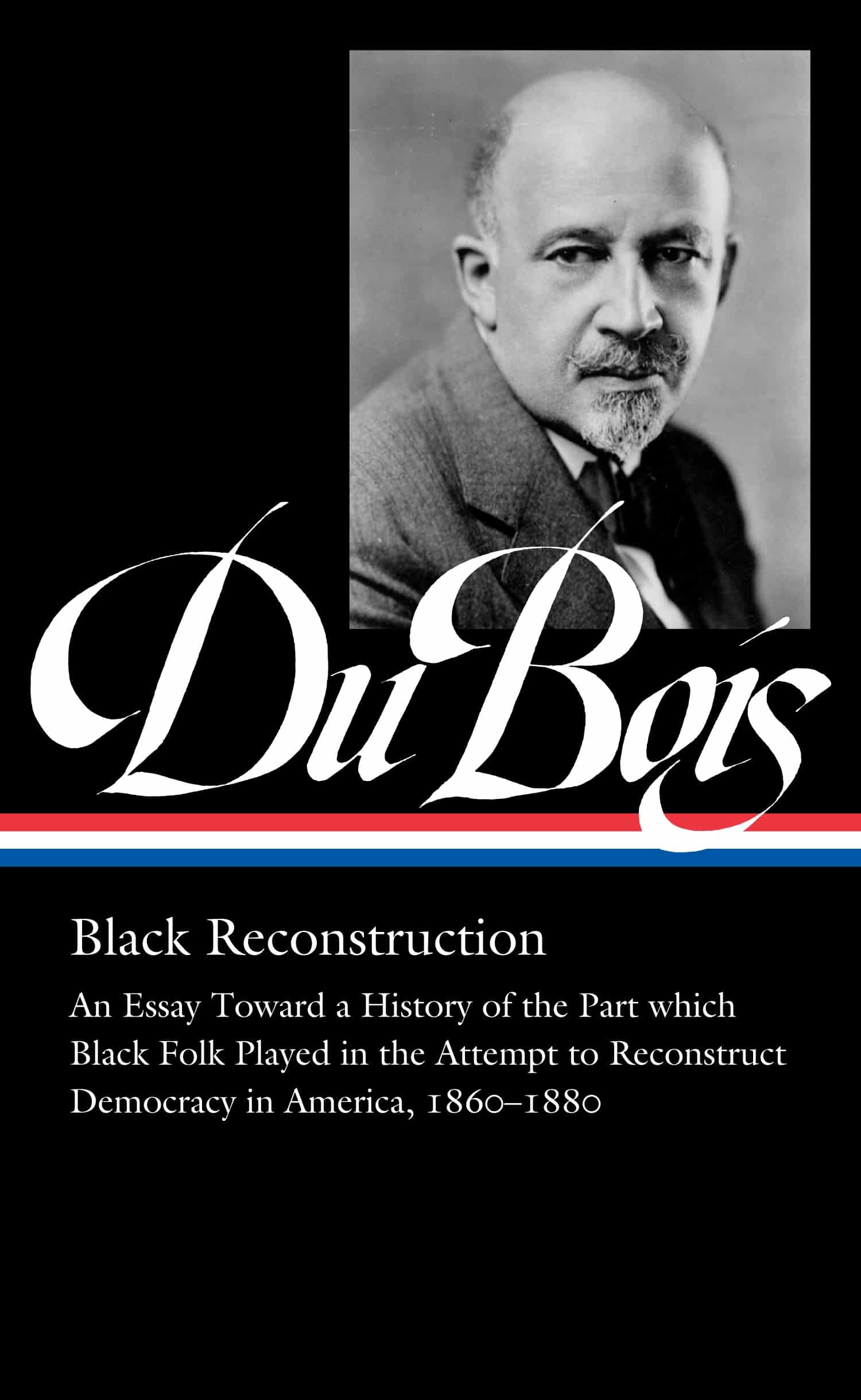

From A People’s History of the United States, chapters 9 and 11.

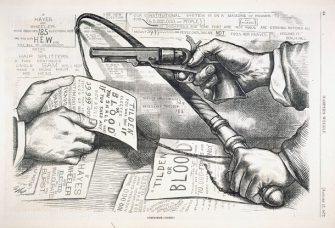

It was the year 1877 that spelled out clearly and dramatically what was happening. When the year opened, the presidential election of the past November was in bitter dispute. The Democratic candidate, Samuel Tilden, had 184 votes and needed one more to be elected: his popular vote was greater by 250,000. The Republican candidate, Rutherford Hayes, had 166 electoral votes. Three states not yet counted had a total of 19 electoral votes; if Hayes could get all of those, he would have 185 and be President. This is what his managers proceeded to arrange. They made concessions to the Democratic party and the white South, including an agreement to remove Union troops from the South, the last military obstacle to the reestablishment of white supremacy there.

“A Truce — Not a Compromise” by Thomas Nast. Harper’s Weekly, 1877 Feb. 17, p. 132. Source: Library of Congress, LC-USZ62-93672

. . . the government of the United States was behaving almost exactly as Karl Marx described a capitalist state: pretending neutrality to maintain order, but serving the interests of the rich. Not that the rich agreed among themselves; they had disputes over policies.

But the purpose of the state was to settle upper-class disputes peacefully, control lower-class rebellion, and adopt policies that would further the long-range stability of the system.

The arrangement between Democrats and Republicans to elect Rutherford Hayes in 1877 set the tone. Whether Democrats or Republicans won, national policy would not change in any important way.

Find resources below to teach outside the textbook about the Reconstruction era.

Learn more in the Zinn Education Project national report, “Erasing the Black Freedom Struggle: How State Standards Fail to Teach the Truth About Reconstruction,” and find teaching resources on Reconstruction below.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn