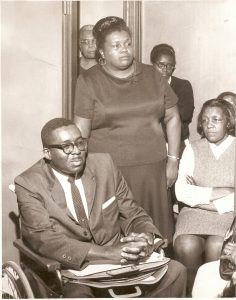

This photo was taken at a Women of Virginia’s 3rd Force meeting, where members discussed voter registration. Joseph A. Jordan Jr., Evelyn T. Butts, and Minnie Brownson pictured. Source: Butts Family Private Collection.

On March 24, 1966, the U.S. Supreme Court banned poll taxes for state and local elections, declaring that “wealth or fee paying has . . . no relation to voting qualifications; the right to vote is too precious, too fundamental to be so burdened or conditioned.”

The decision closed a loophole in the 24th Amendment, which had abolished poll taxes for federal elections but did not address poll taxes imposed for state and local elections.

The lawsuit that resulted in the demise of poll taxes was initiated on Nov. 29, 1963, by Joseph A. Jordan Jr., a civil rights attorney in Norfolk, Virginia, on behalf of his client, Evelyn T. Butts. Butts was an African American voting-rights crusader and seamstress, who was already busy supporting her three daughters and disabled husband, a World War II veteran. In March 1964, four residents of Fairfax County, Virginia — Annie E. Harper, Curtis Burr, Myrtle Burr, and Gladys A. Berry — filed a similar lawsuit, and the cases eventually were consolidated as Harper v. Virginia State Board of Elections.

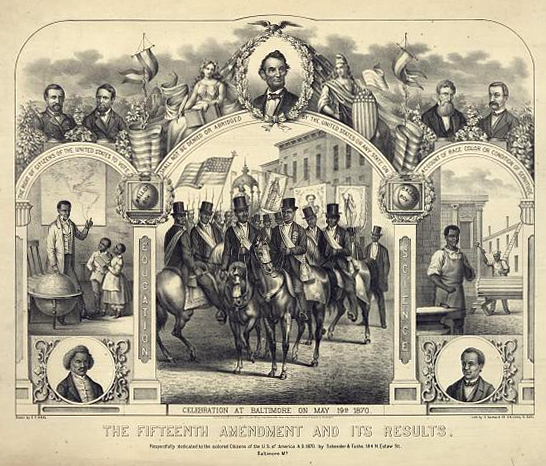

Virginia’s poll tax had been established in the state’s revised constitution of 1902 amid a movement among the former Confederate states to disenfranchise African Americans through a combination of poll taxes, literacy tests, and other devices of Jim Crow repression that undid Black political gains from the Reconstruction era. White supremacist politicians who engineered the poll taxes and other voter-suppression schemes often boasted of their work. Their ilk included Virginia’s Carter Glass, who proclaimed that the former Confederate states: “curse and deride and spit upon the 15th amendment — and have no intention of letting the Negro vote” because “White supremacy is too precious a thing to surrender for the sake of a theoretical justice that would let a brutish African deem himself the equal of white men and women in Dixie.”

The Virginia poll tax of $1.50 a year, which had to be paid three years consecutively and at least six months before an election, hurt African Americans the most but also stripped voting rights from many poor whites. However, by 1964, most states had decided to eliminate this discriminatory levy — leaving only Virginia, Alabama, Mississippi, and Texas as diehards in imposing poll taxes for state and local elections.

The Virginia poll tax of $1.50 a year, which had to be paid three years consecutively and at least six months before an election, hurt African Americans the most but also stripped voting rights from many poor whites. However, by 1964, most states had decided to eliminate this discriminatory levy — leaving only Virginia, Alabama, Mississippi, and Texas as diehards in imposing poll taxes for state and local elections.

The Supreme Court’s landmark decision, written by Justice William O. Douglas for the 6-3 majority, found that Virginia had violated the equal protection provision of the 14th Amendment and emphasized that “Fee payments or wealth, like race, creed, or color, are unrelated to the citizen’s ability to participate intelligently in the electoral process.”

Norfolk voting-rights crusader Evelyn T. Butts, standing, and her lawyer, civil rights attorney Joseph A. Jordan Jr. Source: Butts Family Private Collection.

Voting rights experts and historians say the high court’s ruling had deep effects on U.S. political history by empowering countless African Americans to participate in state and local elections and reinforcing democratic ideals. Alexander Keyssar, in The Right to Vote: The Contested History of Democracy in the United States, observes that “Almost two centuries after the nation’s founding, economic restrictions on voting had been abolished in all general elections. … What once had been believed to be the most essential qualification for the franchise — the possession of property — officially had been judged irrelevant.”

Ronnie L. Podolefsky, in “Illusion of Suffrage: Female Voting Rights and the Women’s Poll Tax Repeal Movement after the Nineteenth Amendment” (Notre Dame L. Rev.839 1998), contends that the 1966 poll tax decision was important to the rights of poor African American women because it “was not decided as an issue of race or of gender, but rather upon one manifestation of the intersection of the two: the inability to participate in the political process by reason of poverty.” And Bruce Ackerman and Jennifer Nou in “Canonizing the Civil Rights Revolution: The People and the Poll Tax” (Northwestern Law Review, Vol. 103, 2009), celebrate the ruling as representing “a larger effort by the American people, during the 1960s, to create a more egalitarian democracy. Harper is not the product of an activist Court, but of an activist people.”

By Michael Knepler, who prepares periodic #tdih posts for the Zinn Education Project. Knepler also shared the entry below on how Evelyn Butts continued to organize after the Supreme Court ruling.

Evelyn Butts

Evelyn Butts (May 22, 1924 – March 11, 1993) did not rest on her laurels after the Supreme Court ruling. “After Butts knocked out the poll tax, she stepped up her door-knocking efforts to enlist and motivate voters,” writes Norfolk Mayor Dr. Kenneth Cooper Alexander in his 2021 biography of Butts, Persistence: Evelyn Butts and the African American Quest for Full Citizenship and Self-Determination. The combination of the abolition of poll taxes and Butts’ community organizing skills helped elect her attorney, Joseph A. Jordan Jr., to the Norfolk City Council in 1968, making him the first African American member of the council since the Reconstruction Era ended in the 1880s. The momentum continued in 1969 with the election of William P. Robinson Sr. as the first Black member of the Virginia House of Delegates from Norfolk, also since Reconstruction.

Yet Butts applied her considerable leadership skills to many civil rights and community issues, including public school desegregation, fair housing, neighborhood improvements, equal employment opportunity and equal pay. Norfolk historian Dr. Tommy L. Bogger described her as “a wizard of community organization.”

Born into poverty and enduring many personal struggles during the Great Depression and World War II, Butts never forgot her roots or how neighbors helped her overcome the hardships. She eventually came to draw on those experiences to take younger women under her wings in various initiatives that combined domestic skills with political activities.

For example, Butts invited neighborhood women to her kitchen to swap ideas about recipes, sewing and child-rearing, while also updating them about the national Civil Rights Movement and local policies involving the Norfolk government and public schools.

Still, attaining, preserving, and expanding voting rights remained central to all of Butts’ endeavors.

Butts transformed her neighborly camaraderie into several community and political organizations that focused on voting. Through these groups, Butts and her allies conducted countless voter-education, voter-registration, and voter-turnout campaigns.

As Butts said, “The struggle for Black men and Black women rests with our right to vote.”

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn