On Aug. 7, 1964 the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution passed with only two opposing votes in the U.S. Senate.

In the opening pages of his autobiography, Secrets: A Memoir of Vietnam and the Pentagon Papers, Daniel Ellsberg describes the dramatic events leading up to the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution in early August 1964. According to the public announcements of President Lyndon Johnson and Defense Secretary Robert McNamara, twice in two days the North Vietnamese had attacked U.S. warships “on routine patrol in international waters,” and engaged in a “deliberate” pattern of “naked aggression”; evidence of both attacks was “unequivocal,” and these had been “unprovoked.”

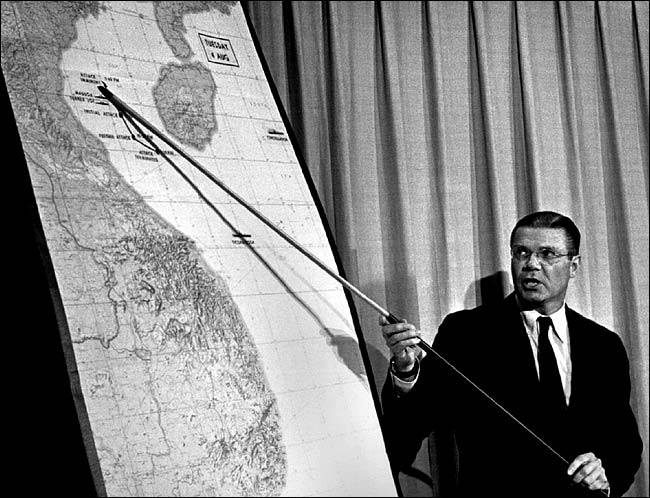

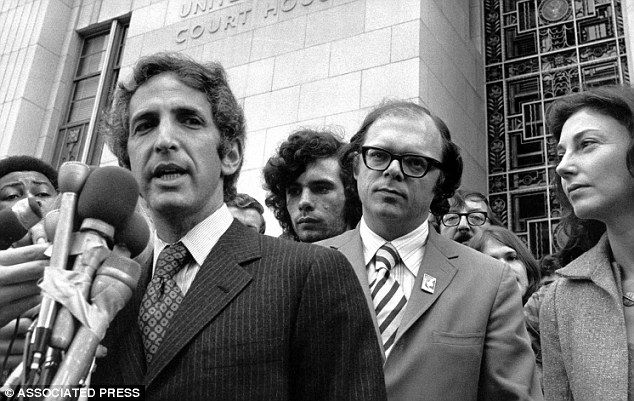

Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara in a post-midnight press briefing at the Pentagon points out action in Gulf of Tonkin, Aug. 4, 1964. Source: © Bob Schutz/AP.

According to Johnson and McNamara, the United States would respond in order to deter future attacks but was planning no wider war. Each of these claims was a lie. Ellsberg had just begun his new job in the Pentagon. As he writes in Secrets,

By midnight on the fourth [of August], or within a day or two, I knew that each one of these assurances was false.

And yet, the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution passed Congress without a single dissent in the House of Representatives, and only two “no” votes in the Senate. It gave the president carte blanche to “take all necessary measures to repel any armed attack against the forces of the United States and to prevent further aggression.” As they say, the rest is history.

One of the most important history lessons to use with students is “Questioning the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution.” (Find this lesson and more free lessons from the Zinn Education Project for teaching outside the textbook about the Vietnam War, at Teaching the Vietnam War: Beyond the Headlines.)

With an understanding and memory of the Gulf of Tonkin, more questions might have been raised about the “weapons of mass destruction” and other current pretenses for war.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn