In Gomillion v. Lightfoot, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled on Nov. 14, 1960 that Tuskegee city officials had redrawn the city’s boundaries unconstitutionally to ensure the election of white candidates in the city’s political races. Tuskegee’s white citizens were trying to change the city’s boundaries to head off the rise in African Americans registering to vote after WWII.

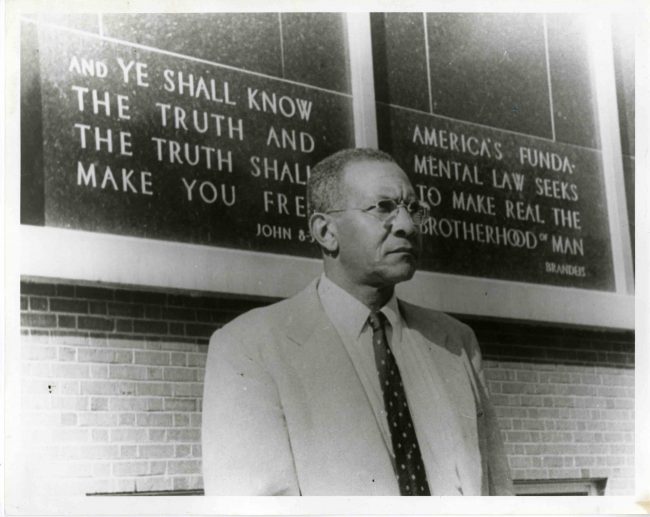

Dr. Charles Gomillion. Source: Tuskegee University Civil Rights Collection

The case was named for Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute (present-day Tuskegee University) professor Charles A. Gomillion, who was lead plaintiff, and the defendant, Tuskegee mayor, Philip M. Lightfoot, among other city officials.

Justice Felix Frankfurter, writing for the majority, held that the act violated the Reconstruction era Fifteenth Amendment, which prohibits states from passing laws depriving citizens of the right to vote, and thus reversed the lower courts’ rulings. In 1961, the results of the decision went into effect; the gerrymandering [read below about the origins of the term] was reversed and the original map was reinstituted.

The case was one of several that would lay the foundation for the passage of the 1965 Voting Rights Act, which outlawed discriminatory voting practices. Continue reading.

Description by Allen Mendenhall, Auburn University from the Encyclopedia of Alabama.

Origins of Term Gerrymandering

Our thanks to Michael Knepler, who prepares periodic #tdih posts for the Zinn Education Project, for providing this background on the term gerrymandering.

Patrick Henry, a powerful antifederalist, engineered what might have been the first political gerrymander in United States history in hopes of thwarting James Madison’s campaign for a seat in the nation’s first Congress. Henry, a former governor of Virginia, was serving in Virginia’s House of Delegates in 1788 when the state legislature devised the state’s first congressional districts on Nov. 13, 1788.

At Henry’s bidding, the House of Delegates designed Virginia’s congressional districts in such a way that they “were specially designed to keep Madison out of office,” according to historian Noah Feldman in his biography, “The Three Lives of James Madison: Genius, Partisan, President.” Under the plan, Madison, who was Henry’s political nemesis, was placed in Virginia’s 5th Congressional District, where he would have to run against Revolutionary War veteran James Monroe. The strategy did not work as Madison won election to the U.S. House of Representatives on February 2, 1789, by 336 votes – 1,308 to 972. (Madison later became the fourth president of the U.S. and Monroe the fifth.)

Many scholars consider Henry’s 1788 manipulation of Virginia’s congressional districts to be the nation’s first gerrymander, although the term “gerrymander” did not come into being until 1812. That’s when Massachusetts Gov. Elbridge Gerry signed legislation that created a partisan district that resembled a salamander, which a political cartoonist nicknamed “gerry-mander.” In an ironic twist of history, Gerry went on to serve as vice president in President James Madison’s second term in office. (Madison’s vice presidents did not fare well. Gerry died in office in 1814, two years after George Clinton, vice president in Madison’s first term, became the first U.S. vice president to die while serving.)

As for the political battles between Patrick Henry and James Madison, historians note that the two men were engaged in a bitter dispute over how much power the federal government should have. Henry unsuccessfully fought against Virginia’s ratification of the U.S. Constitution, and Madison feared that Henry would continue to push for a second constitutional convention as part of an effort to weaken the central government and give states more power.

Find resources below to teach outside the textbook about voting rights.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn