On March 18, 1963, the Supreme Court ruled in Gideon v. Wainwright.

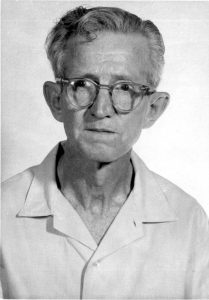

The case involved Clarence Earl Gideon, a poor man from Florida who was convicted of breaking into a pool hall. He couldn’t afford a lawyer. None was provided for him when he asked for one at trial. In its decision, the Supreme Court ruled in favor of Gideon, finding state courts are required under the Sixth Amendment to provide a lawyer in criminal cases for defendants unable to afford their own.

However, public defenders are finding themselves overwhelmed with cases. Watch the Democracy Now! segment, “Young Public Defenders Brave Staggering Caseloads, Low Pay to Represent the Poor,” about the challenges to the implementation of this ruling today, based on the documentary Gideon’s Army.

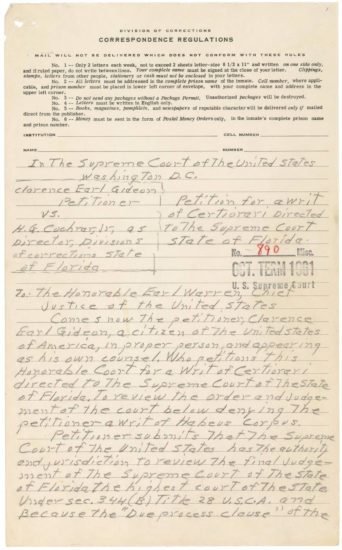

Clarence Earl Gideon’s handwritten petition for a writ of cert to the Supreme Court. Source: National Archives

Description above adapted from Democracy Now!

Background on the case from Thirteen: Media with Impact:

The Gideon v. Wainwright (1963) case began with the 1961 arrest of Clarence Earl Gideon. Gideon was charged with breaking and entering into a Panama City, Florida, pool hall and stealing money from the hall’s vending machines.

At trial, Gideon, who could not afford a lawyer himself, requested that an attorney be appointed to represent him. He was told by the judge that Florida only provided attorneys to indigent defendants charged with crimes that might result in the death penalty if they were found guilty. After he was sentenced to five years in prison, Gideon filed a habeas corpus petition (or petition for release from unjust imprisonment) to the Florida Supreme Court, claiming that his conviction was unconstitutional because he lacked a defense attorney at trial. After the Florida Supreme Court denied his petition, Gideon appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court, which reviewed his case in 1963.

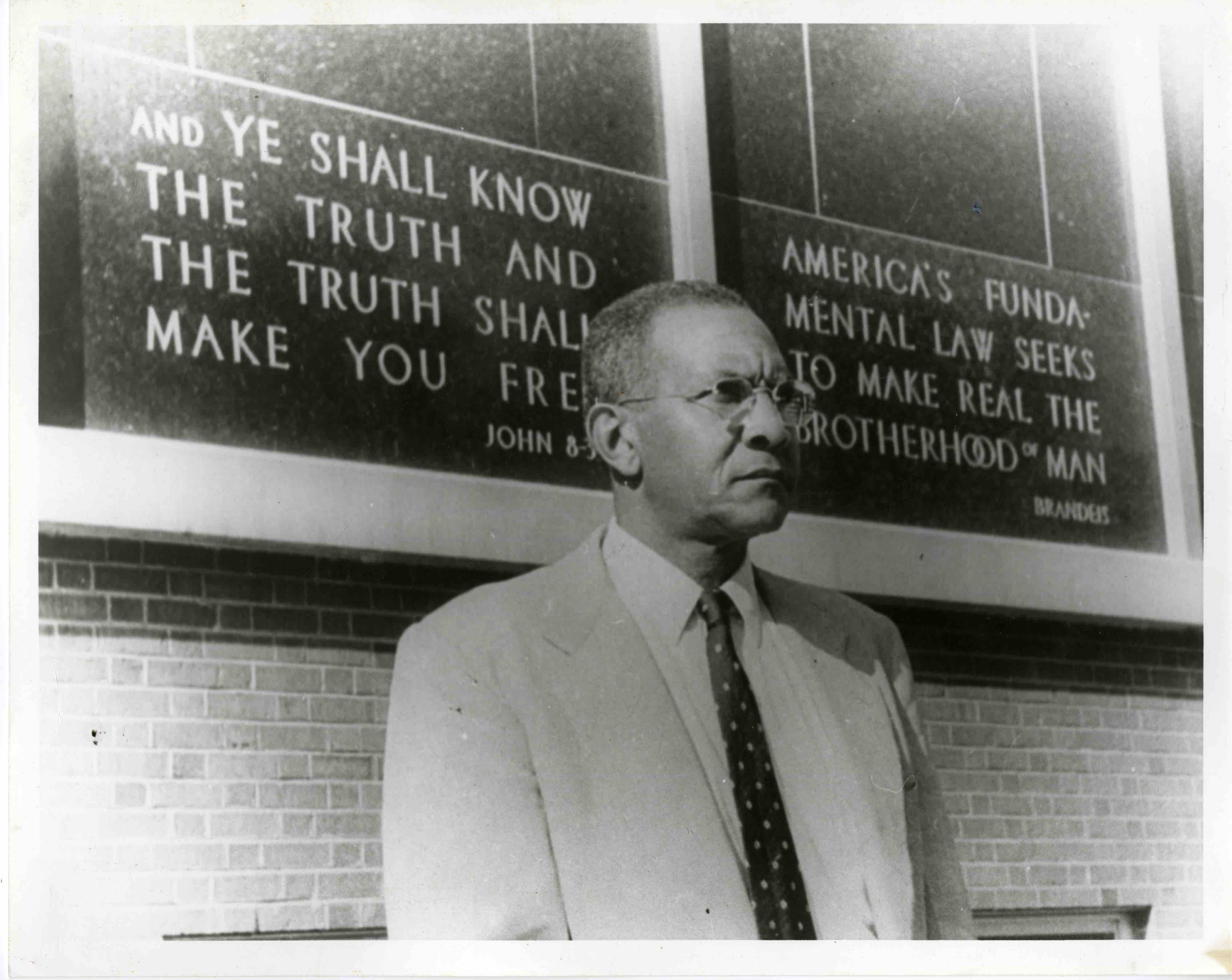

The Supreme Court, in a unanimous decision written by Justice Hugo Black, ruled that Gideon’s conviction was unconstitutional because Gideon was denied a defense lawyer at trial. The Court ruled that the Constitution’s Sixth Amendment gives defendants the right to counsel in criminal trials where the defendant is charged with a serious offense even if they cannot afford one themselves; it states that “in all criminal prosecutions, the accused shall enjoy the right to have the Assistance of Counsel for his defense.”

Before the 1930s, the Supreme Court interpreted this language as only forbidding the state from denying a defense attorney at trial. From the 1930s on, however, the Court interpreted the amendment as requiring the state to provide defense attorneys in capital trials (see Powell v. Alabama [1932]). Continue reading.

For more historic Supreme Court cases, see A People’s History of the Supreme Court: The Men and Women Whose Cases and Decisions Have Shaped Our Constitution.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn